United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1801–1922 | |||||||||||||

|

Anthem: "God Save the King"/"Queen"

|

|||||||||||||

The United Kingdom in 1914

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital and largest city

|

London 51°30′N 0°7′W / 51.500°N 0.117°W |

||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | British | ||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||

|

• 1801–1820

|

George III | ||||||||||||

|

• 1820–1830

|

George IV | ||||||||||||

|

• 1830–1837

|

William IV | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||||||

| House of Lords | |||||||||||||

| House of Commons | |||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| 1 January 1801 | |||||||||||||

| 6 December 1921 | |||||||||||||

| 6 December 1922 | |||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

|

• 1911 census

|

45,221,000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency |

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

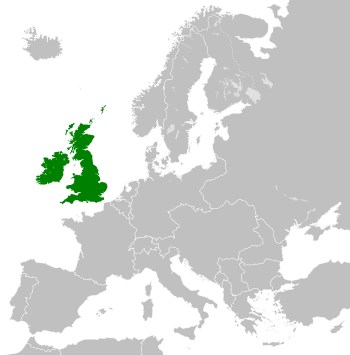

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a country that existed from 1801 to 1922. It was formed when the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland joined together. This happened because of the Acts of Union 1800. In 1922, a large part of Ireland became independent as the Irish Free State. The rest of the country was later renamed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1927.

After helping to defeat France in the Napoleonic Wars, the United Kingdom built a very strong Royal Navy. This navy helped the British Empire become the most powerful country in the world for about 100 years. From the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo until World War I, Britain was mostly at peace with other major countries. One exception was the Crimean War against the Russian Empire. However, Britain did fight many wars in Africa and Asia, like the Opium Wars with the Qing Dynasty, to expand its empire.

In the second half of the 1800s, the British government started giving more power to local governments in colonies where many white settlers lived. This led to countries like Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and South Africa becoming self-governing areas called dominions. These dominions were still part of the British Empire, but they managed their own affairs. London mainly handled their foreign policy.

Britain experienced fast growth in factories and industries, which started before 1801 and continued until the mid-1800s. The Great Irish Famine in the mid-1800s caused many people in Ireland to die or leave. This led to more calls for changes to land ownership in Ireland. The 1800s were a time of great economic change and growth for Britain. It became a leader in industry, trade, and finance around the world. Many people moved from Britain and Ireland to British colonies and the United States. The British Empire grew to include large parts of Africa and South Asia.

British officials managed the empire locally, and democratic ideas began to develop. British India, a very important part of the empire, saw a short rebellion in 1857. In foreign policy, Britain believed in free trade. This allowed British and Irish business people to work successfully in many independent countries, especially in South America. Britain did not make permanent military alliances until the early 1900s. Then, it started working with Japan, France, and Russia, and became closer to the United States.

Many people in Ireland wanted self-governance. This led to the Irish War of Independence. In 1922, Britain recognized the Irish Free State. This new state was a dominion, meaning it was largely self-governing but still connected to the British Empire. It was no longer part of the United Kingdom. Six counties in northeastern Ireland, known as Northern Ireland, had already gained a limited form of self-rule in 1920. They chose to stay part of the United Kingdom. Because of these changes, the British state was renamed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1927. The United Kingdom today is the same country that remained after Ireland left.

Contents

How the United Kingdom Changed (1801-1837)

Joining Great Britain and Ireland

Ireland had a short time of limited independence. This ended after the Irish rebellion of 1798 during Britain's war with France. The British government worried that an independent Ireland might side with France. So, they decided to unite the two countries. Laws were passed in both parliaments, and the union began on January 1, 1801.

The Irish were told that if they gave up their own parliament, Catholics would gain more rights. This meant removing restrictions on Roman Catholics in both Great Britain and Ireland. However, King George III strongly opposed this. He stopped his government from making these changes.

Fighting the Napoleonic Wars

During the War of the Second Coalition (1799–1801), Britain took over many French and Dutch colonies. However, many British soldiers died from tropical diseases. When the war ended with the Treaty of Amiens, Britain agreed to give back most of the lands it had taken. This peace was short-lived. Napoleon continued to challenge Britain, trying to stop trade and occupying Hanover, a German region linked to the British king.

In May 1803, war started again. Napoleon's plans to invade Britain failed because his navy was not strong enough. In 1805, Lord Nelson's Royal Navy defeated the French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar. This was the last major naval battle of the Napoleonic Wars.

In 1806, Napoleon created the Continental System. This policy aimed to weaken Britain by blocking trade with French-controlled Europe. The British Army was much smaller than France's army. However, the Royal Navy successfully stopped France's trade outside Europe. It seized French ships and colonies. Britain had a strong industrial economy and controlled the seas, allowing it to trade with its colonies and the United States.

In 1808, a Spanish uprising allowed Britain to gain a foothold in Europe. The Duke of Wellington slowly pushed the French out of Spain. In early 1814, Wellington invaded southern France as Napoleon was being defeated by other European powers in the east. After Napoleon surrendered and was exiled, peace seemed to return. But Napoleon came back in 1815. The armies of Wellington and Blucher finally defeated Napoleon at Waterloo.

War of 1812 with the United States

While fighting Napoleon, Britain also had a war with the United States from 1812 to 1814. This war was caused by trade disagreements, British support for Native American tribes, and the British forcing American sailors into their navy. Britain paid little attention to this war until Napoleon was defeated in 1814.

American ships won some battles against the Royal Navy, which was short on sailors. In 1814, Britain increased its efforts, winning battles like Queenston Heights and burning Washington D.C. However, British invasions of New York and New Orleans failed. The war ended with no changes to the borders, leading to two centuries of peace between the two countries.

Social Changes and Challenges

After the Napoleonic Wars, Britain was a different country. Factories and cities grew, and society became less rural. The time after the war saw economic problems, bad harvests, and rising prices. This led to widespread social unrest. British leaders were very traditional and worried about revolutionary ideas like those in France.

Despite few signs of revolution, Britain passed strict laws, like the "Six Acts" in 1819. These laws limited protests and allowed local officials to stop any disturbances. In 1819, factory workers in industrial areas demanded better wages and protested. The most famous event was the "Peterloo Massacre" in Manchester on August 16, 1819. A local militia charged into a peaceful crowd of 60,000 people who were asking for changes to how Parliament was elected. Eleven people died, and hundreds were hurt. This event shocked many people and became a symbol of the government harshly stopping peaceful protests. By the late 1820s, with the economy improving, many of these strict laws were removed. In 1828, new laws protected the rights of religious groups who were not part of the Church of England.

Foreign Policy Leaders

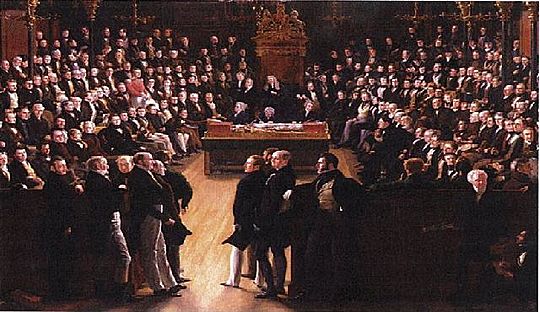

Three important men shaped British foreign policy from 1810 to 1860: Viscount Castlereagh (1812–22), George Canning (1807–1829), and Viscount Palmerston (1830–1865).

Britain paid for the alliance that defeated Napoleon. This alliance was kept together at the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15. Castlereagh played a key role in Vienna. He pushed for a mild peace with France, believing harsh terms would lead to more problems. He wanted a "balance of power" in Europe, so no single nation could try to conquer the continent again. The Congress of Vienna led to a century of peace in Europe, with no major wars until the Crimean War (1853–56). Britain also supported constitutional governments and recognized the independence of Spain's American colonies. British businesses and investors played a big part in the economies of many Latin American countries.

Whig Reforms of the 1830s

George IV (1820–30) was a weak king who let his ministers run the government. He was unpopular, especially when he tried to divorce his wife, Queen Caroline. His brother, William IV (1830–37), was also not very involved in politics.

Earl Grey, Prime Minister from 1830 to 1834, and his Whig Party made several big changes. They updated laws for the poor, limited child labour, and, most importantly, changed the British voting system with the Reform Act 1832. Also, Catholic emancipation was finally granted in 1829, removing most restrictions on Roman Catholics. In 1832, Parliament abolished slavery throughout the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. The government paid £20,000,000 to slave owners (mostly rich plantation owners in England) and freed the slaves, especially those in the Caribbean.

The Whigs strongly supported the Reform Act 1832. This law expanded who could vote and ended the system of "rotten boroughs" (where a few people controlled elections). Instead, power was given based on population. It added 217,000 voters in England and Wales. The main effect was to reduce the power of landowners and increase the power of the middle class, who now had a voice in Parliament. However, most workers, clerks, and farmers still could not vote until 1867. The wealthy upper class still largely controlled the government, church, army, navy, and high society.

What was Chartism?

Chartism started after the 1832 Reform Bill did not give voting rights to working-class people. In 1838, Chartists created the People's Charter. It demanded that all men could vote, election districts be equal in size, voting be done by secret ballot, Members of Parliament be paid (so poor men could serve), parliaments be elected every year, and property requirements for voting be removed. The ruling class saw this movement as dangerous. The Chartists could not force major changes to the constitution.

Leaders of the Era

Prime Ministers during this time included: William Pitt the Younger, Lord Grenville, Duke of Portland, Spencer Perceval, Lord Liverpool, George Canning, Lord Goderich, Duke of Wellington, Lord Grey, Lord Melbourne, and Sir Robert Peel.

The Victorian Era (1837-1901)

The Victorian era is named after Queen Victoria, who ruled from 1837 to 1901. This period was the peak of Britain's Industrial Revolution and the British Empire. Victoria became queen at 18. Her long reign saw Britain become very powerful economically and politically. New inventions like steamships, railroads, photography, and the telegraph appeared. Britain mostly stayed out of European politics during this time.

Victorian Foreign Policy

How Britain Dominated Trade

After defeating France in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815), the UK became the main naval and imperial power in the 1800s. London was the world's largest city around 1830. With its navy unchallenged at sea, British power was called Pax Britannica ("British Peace"). This was a time of relative peace in Europe and the world (1815–1914). By 1851, Britain was known as the "workshop of the world." Using free trade and financial investments, Britain had a lot of influence in many countries outside Europe and its formal empire, especially in Latin America and Asia.

Relations with Russia, France, and the Ottomans

Britain worried about the possible collapse of the Ottoman Empire. If it fell apart, other countries would fight over its land, possibly leading to war. To prevent this, Britain tried to stop Russia from taking Constantinople and the Bosphorus Strait. Britain also wanted to prevent Russia from threatening India through Afghanistan. In 1853, Britain and France fought against Russia in the Crimean War. They captured the Russian port of Sevastopol, forcing Tsar Nicholas I to ask for peace.

Another war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire in 1877 led to European countries stepping in to negotiate. The Congress of Berlin stopped Russia from imposing a harsh treaty on the Ottoman Empire. Despite being allies with France in the Crimean War, Britain did not fully trust Napoleon III of France. He was building up his navy and expanding his empire.

The American Civil War

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), British leaders favored the Confederacy because it supplied cotton for British textile mills. Prince Albert helped prevent a war between Britain and the US in late 1861. However, most British people supported the Union. Very little cotton came from the South due to the US Navy's blockade. Trade with the Union grew, and many young British men joined the Union Army.

In September 1862, Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves. After this, supporting the Confederacy meant supporting slavery, so European countries did not intervene. British companies built and operated fast ships to smuggle weapons into the Confederacy for profit. This caused a major diplomatic problem with the US. It was resolved in 1872 when Britain paid reparations for the warships built for the Confederacy.

Expanding the Empire

In 1867, Britain united most of its North American colonies into the Dominion of Canada. This gave Canada self-government and control over its own defense. However, Canada did not have an independent foreign policy until 1931. The second half of the 1800s saw a huge expansion of Britain's colonial empire, mostly in Africa. The idea of the British flag flying "from Cairo to Cape Town" became a reality after World War I. With colonies on six continents, Britain had to defend its vast empire. It did this with a volunteer army, unlike other major European powers that used conscription. Some people wondered if the country was trying to do too much.

The rise of the German Empire after its creation in 1871 presented a new challenge. Germany, along with the United States, threatened to take Britain's place as the world's leading industrial power. Germany gained colonies in Africa and the Pacific. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck managed to keep general peace through his balance of power strategy. However, when William II became emperor in 1888, he dismissed Bismarck. William II used aggressive language and planned to build a navy to rival Britain's.

Britain had taken control of the Cape Colony from the Netherlands during the Napoleonic Wars. It then co-existed with Dutch settlers, called "Boers" or "Afrikaners," who had moved further away and created their own republics. The British wanted control over these new countries. The Boers fought back in the War in 1899–1902. The Boers used guerrilla warfare against the powerful British Empire. This made it a difficult fight for the British soldiers. However, Britain's larger numbers, better equipment, and sometimes harsh tactics led to a British victory. The war was costly and criticized by many. The Boer republics were merged into the Union of South Africa in 1910. This new union had internal self-government, but London controlled its foreign policy, and it was part of the British Empire.

Victorian Leaders

Prime Ministers during the Victorian era included: Lord Melbourne, Sir Robert Peel, Lord John Russell, Lord Derby, Lord Aberdeen, Lord Palmerston, Benjamin Disraeli, William Ewart Gladstone, Lord Salisbury, and Lord Rosebery.

Queen Victoria's Influence

Queen Victoria gave her name to an era of British power, especially in the vast British Empire. She played a small role in politics but became a strong symbol of the nation, the empire, and proper behavior. Her success came from how she presented herself: first as an innocent young woman, then a devoted wife and mother, a grieving widow, and finally a grandmotherly leader.

Disraeli's Role

Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881), who was prime minister in 1868 and from 1874–80, is a famous figure in the Conservative Party. He cared about protecting traditional values and leaders. He believed in strong national leadership to deal with new ideas and problems. Disraeli was known for strongly supporting the expansion of the British Empire. This was different from Gladstone, who was less keen on imperialism. Gladstone criticized Disraeli's policies of taking more land and showing off military power. However, Gladstone himself also expanded the empire in Egypt.

Disraeli gained support by warning about a supposed Russian threat to India. He also worked to reduce tensions between different groups in society, like town and country, landowners and farmers, and different religious groups.

Gladstone's Leadership

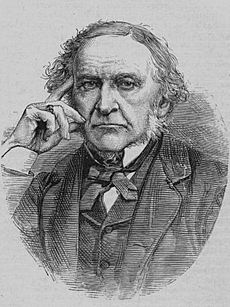

William Ewart Gladstone (1809–1898) was the Liberal Party's main leader. He served as prime minister four times (1868–74, 1880–85, 1886, and 1892–94). His financial policies focused on balanced budgets, low taxes, and limited government involvement in the economy. These policies worked well for a growing capitalist society.

Gladstone was a powerful speaker who appealed to British workers and the lower middle class. He brought a new moral approach to politics. His strong beliefs often angered his upper-class opponents, including Queen Victoria, who preferred Disraeli. His foreign policy aimed to create peace in Europe through cooperation and trust, rather than conflict.

Lord Salisbury's Influence

Conservative Prime Minister Lord Salisbury (1830–1903) was a talented leader and a symbol of traditional, aristocratic conservatism. Some historians see him as a great foreign minister but very traditional in domestic affairs. Others say he successfully "held back the popular tide for twenty years."

Early 20th Century (1901-1922)

Prime Ministers from 1900 to 1923 included: Marquess of Salisbury, Arthur Balfour, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, Herbert Henry Asquith, David Lloyd George, and Andrew Bonar Law.

The Edwardian Era (1901–1914)

Queen Victoria died in 1901. Her son, Edward VII, became king. This started the Edwardian Era, known for its grand displays of wealth, unlike the more serious Victorian Era. In the early 1900s, new things like movies, cars, and airplanes became common. There was a feeling of great hope for the future. Social reforms continued, and the Labour Party was formed in 1900.

Edward died in 1910, and his son, George V, became king (1910–36). George V was a popular and hardworking monarch. He set the example for modern British royalty, focusing on middle-class values. He understood the British Empire better than his prime ministers.

This era was prosperous, but political problems were growing. There were serious social and political issues from the Irish crisis, worker strikes, women's suffrage movements, and political fights in Parliament. At one point, it seemed the Army might even refuse orders about Ireland. No solutions were found before World War I began in 1914, which put domestic issues on hold.

The Great War (World War I)

After a difficult start, Britain, led by David Lloyd George, successfully used its people, industries, money, empire, and diplomacy to defeat the Central Powers. The economy grew by about 14% from 1914–18, even with many men serving in the military. In contrast, the German economy shrank by 27%. The war meant less civilian spending, with more resources going to making weapons. The government's share of the country's total output jumped from 8% in 1913 to 38% in 1918. Britain had to use up its financial savings and borrow a lot of money from the U.S.

Britain entered the war to protect Belgium from Germany. It quickly took on the role of fighting Germans on the Western Front and taking over Germany's colonies. The romantic ideas about war quickly disappeared as the fighting in France turned into trench warfare. On the Western Front, British and French forces repeatedly attacked German trenches in 1915–16. These attacks killed and wounded hundreds of thousands but gained very little ground. By 1916, with fewer volunteers, the government started conscription (forced military service) in Britain to keep the army strong. Many women took factory jobs to produce weapons.

The Navy continued to control the seas. The only major naval battle, the Battle of Jutland in 1916, was a draw. Germany was blockaded and faced food shortages. It tried to fight back with submarines, even though this risked war with the powerful neutral United States. The waters around Britain were declared a war zone where any ship could be attacked. After the passenger ship Lusitania was sunk in May 1915, killing over 100 American passengers, protests from the United States led Germany to stop unrestricted submarine warfare for a time.

In 1917, after defeating Russia, Germany believed it could win on the Western Front. It planned a huge attack in 1918 and resumed sinking all merchant ships without warning. The United States entered the war with the Allies in 1917. The US provided the needed soldiers, money, and supplies. On other fronts, British, French, Australians, and Japanese forces took over Germany's colonies. Britain fought the Ottoman Empire, suffering defeats in the Gallipoli Campaign and in Mesopotamia. Britain also encouraged Arabs to help expel the Turks from their lands.

By 1917, exhaustion and war-weariness grew. The fighting in France continued with no end in sight. Germany's attacks in spring 1918 failed. With a million American Expeditionary Forces arriving by May 1918, the Germans realized they were overwhelmed. Germany agreed to an Armistice (a surrender) on November 11, 1918.

The war changed British society. The army, which was small before the war, grew to about five million people by 1918. The new Royal Air Force was almost as big as the pre-war army. The nearly three million casualties were known as the "lost generation." This left society scarred, and some felt their sacrifice was not fully appreciated.

After the War

Britain and its allies won the war, but at a terrible human and financial cost. This led to a feeling that wars should never be fought again. The League of Nations was created with the idea that countries could solve their problems peacefully, but these hopes were not fully realized.

After the war, Britain gained the German colony of Tanganyika and part of Togoland in Africa. Britain also received control over Palestine, which became a homeland for Jewish settlers, and Iraq, formed from three Ottoman provinces. Iraq became fully independent in 1932. Egypt, which Britain had controlled since 1882, became independent in 1922, though British troops stayed there until 1956.

At home, the Housing Act of 1919 led to affordable council housing, allowing people to move out of old city slums. The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave women householders the right to vote. Full equal voting rights for all women came in 1928. The Labour Party became the second-largest party, replacing the Liberal Party, and gained significant success in the 1922 general election.

Ireland's Path to Independence

The Fight for Irish Home Rule

Part of the agreement to join Great Britain and Ireland in 1801 was that laws against Catholics in Ireland would be removed. However, King George III refused, saying it would break his promise to defend the Anglican Church. A campaign led by lawyer Daniel O'Connell and the death of George III led to Catholic Emancipation in 1829. This allowed Roman Catholics to be members of the UK Parliament.

O'Connell's main goal was to end the Act of Union with Great Britain. In 1843, he wrongly declared that this would happen that year. When potato blight hit Ireland in 1846, many rural people had no food. This was because cash crops were being exported to pay rents. British politicians believed in laissez-faire, meaning they thought the government should not interfere. While private groups raised money, a lack of strong government action turned the problem into a disaster. Many poor farmers died during what is known in Ireland as the "Great Hunger".

A group called Unionists wanted to keep the Union. A new, moderate nationalist movement, the Home Rule League, was started in the 1870s by Isaac Butt. After Butt's death, the Home Rule Movement, also known as the Irish Parliamentary Party, became a major political force under Charles Stewart Parnell.

Parnell's movement campaigned for "Home Rule." This meant Ireland would govern itself as a region within the United Kingdom. Two Home Rule Bills (1886 and 1893) were introduced by Liberal Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. However, neither became law, mainly because the Conservative Party and the House of Lords opposed them. This issue caused much disagreement in Ireland. Many Unionists, mostly in Ulster, feared that a Catholic-led Parliament in Dublin would treat them unfairly or impose Catholic rules. Most of Ireland was agricultural, but six counties in Ulster had heavy industry. They worried about tariffs (taxes on goods) that might be imposed.

Irish demands varied, from O'Connell's "repeal" of the Union to "self-rule" like that given to Canada in 1867. Ireland was no closer to home rule by the mid-1800s, and rebellions in 1848 and 1867 failed. As more people gained the right to vote in Ireland, anti-Union parties did better. In 1874, Home Rulers won most seats in Ireland. By 1882, Charles Stewart Parnell led the Home Rule movement.

The 1885 United Kingdom general election resulted in no single party having a majority. The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) held the balance of power. They first supported the Conservatives. But when news leaked that Liberal leader William Ewart Gladstone was thinking about Home Rule, the IPP switched support to the Liberals.

Gladstone's First Home Rule Bill was similar to the self-government given to British colonies like Canada. Irish Members of Parliament would vote in a separate Dublin parliament for domestic matters. Foreign policy and military affairs would stay with London. Gladstone's ideas did not go as far as most Irish nationalists wanted, but they were too radical for both Irish and British unionists. His First Home Rule Bill was defeated in the House of Commons. Gladstone then took the issue to the public in the 1886 United Kingdom general election. However, the unionists (Conservatives plus Liberals who disagreed) won a majority.

Before the 1892 United Kingdom general election, Parnell was involved in a scandal, and the IPP split. Parnell died unpopular in Ireland. The 1892 election gave pro-Home Rule parties a small majority. Gladstone introduced a Second Home Rule Bill in 1893. This time, it passed the Commons but was defeated by the Conservative-dominated House of Lords.

Home Rule in Question

With the Conservatives in power in the 1890s, Home Rule became less central to British politics. However, the Conservative government also thought that if they improved conditions in Ireland, people would be happier. This was called "killing home rule with kindness." Reforms included the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 and the Wyndham Land Act. Between 1868 and 1908, spending on Ireland increased, land was bought from landlords and given to small farmers, local government became more democratic, and more people could vote. But even with these changes, Irish unhappiness did not end. British governments realized they needed to address Irish demands for national recognition and self-determination.

Some Britons began to accept Irish nationalism. British liberals supported home rule because the Irish people had repeatedly elected Nationalists, showing they no longer wanted to be governed by the United Kingdom. Unionists, however, believed that giving Ireland independence would allow other European powers to use it as a base to attack Britain.

The Liberals returned to power in 1905. After a disagreement with the House of Lords, a larger constitutional conflict arose, leading to two general elections in 1910. The second election in December 1910 meant the Liberals needed the support of the Irish Parliamentary Party, led by John Redmond. Redmond agreed to support the Liberals in exchange for a new Home Rule Bill and the removal of the House of Lords' power to veto laws. This was achieved with the Parliament Act 1911.

The Irish Parliamentary Party's support was rewarded with the Third Home Rule Bill in 1912. With the House of Lords' veto power gone, Home Rule seemed certain. However, the Bill faced strong opposition from unionists, especially in the mostly Protestant province of Ulster. The Bill finally became law in September 1914, a few weeks after World War I began. But its implementation was immediately put on hold for the war's duration.

The situation in Ireland worsened. Unionist Ulster Volunteers and Nationalist Irish Volunteers were openly training and importing weapons, preparing for conflict. World War I made tensions even worse. Unionists and most Nationalists in the Irish Parliamentary Party encouraged volunteers to fight for the Allied cause. These formed three Irish divisions in the British Army. On the other hand, Republican followers were unsure about the war, seeing it as Britain's conflict, not Ireland's.

The Easter Rising and Independence

The Easter Rising of 1916 was planned to create a fully independent Irish Republic. It was put down after a week of fighting. However, the quick executions of 15 leaders of the uprising angered many Catholics and nationalists. After the rebellion, the government decided in May 1916 that the 1914 Home Rule Act should be put into action.

After six months of talks, no agreement was reached on whether Ulster would be under the new Dublin parliament. Asquith made another attempt to implement Home Rule in 1917. However, a decision by Lloyd George in April 1918 to link Home Rule with extending conscription to Ireland caused mass anti-conscription protests in Dublin. This marked the end of an era and led to a shift in public opinion towards Sinn Féin and physical force separatism. This sealed the fate of Home Rule and led to the decline of the Irish Parliamentary Party in the 1918 general elections.

The solution was to create two Irish parliaments, leading to the Government of Ireland Act 1920. On December 6, 1922, Ireland formed a new dominion, the Irish Free State. As expected, Northern Ireland (six counties in Ulster) immediately chose to opt out of the new state. The union of Great Britain with part of Ireland was renamed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. This is its name today.

Monarchs of the United Kingdom (1801-1922)

Until 1927, the monarch's title included "of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland." In 1927, "United Kingdom" was removed from the title. It was restored in 1953, with "Ireland" replaced by "Northern Ireland."

- George III (1801–1820; monarch from 1760)

- George IV (1820–1830)

- William IV (1830–1837)

- Victoria (1837–1901)

- Edward VII (1901–1910)

- George V (1910–1922; title used until 1927 but remained monarch until his death in 1936)

Images for kids

-

Lord Palmerston addressing the House of Commons during the debates on the Treaty of France, February 1860

-

Jeremy Bentham's panopticon prison (1791 drawing by Willey Reveley)

-

Queen Victoria reigned from 1837 to 1901 (1882 photograph)

-

The British Empire in 1910

-

Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone

-

George V, the last British king to be styled as King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

See also

In Spanish: Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda para niños

In Spanish: Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |