International relations (1814–1919) facts for kids

This article is about how countries around the world, especially the most powerful ones, got along from 1814 to 1919. This time started after the big wars led by Napoleon and the important Congress of Vienna meeting. It ended after World War I and the peace talks in Paris.

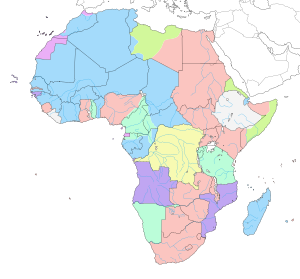

During this period, countries like Great Britain, the United States, France, Germany (which used to be Prussia), and later Italy and Japan grew very quickly. They became strong because of new factories and industries. This led them to compete for power and land all over the world, especially in Africa. This competition was called the Scramble for Africa in the 1880s and 1890s. Its effects are still felt today.

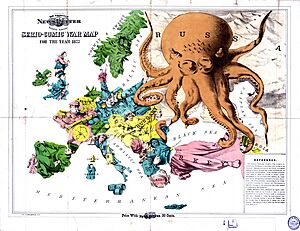

Britain, with its huge empire and powerful Royal Navy, was the strongest nation for a long time. But then, a united Germany started to challenge its power. This century was mostly peaceful, with no major wars between the biggest countries, except for a period from 1853 to 1871. There were also some wars between Russia and the Ottoman Empire. After 1900, a series of wars in the Balkan region eventually exploded into World War I (1914–1918). This war was much bigger and more destructive than anyone expected.

In 1814, there were five main "great powers": France, Britain, Russia, Austria (later Austria-Hungary), and Prussia (later the German Empire). Italy joined this group after it became a united country in 1860. By 1905, Japan and the United States, which were growing fast, also became great powers. Countries like Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro were still part of the weakening Ottoman Empire until they gained independence around 1908–1912.

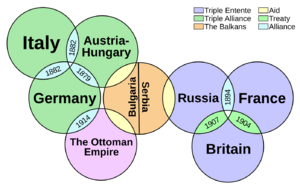

By 1914, just before World War I, Europe had two main groups of allies. The Triple Entente included France, Britain, and Russia. The Triple Alliance had Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. Italy stayed neutral at first but joined the Entente in 1915. The Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria joined Germany and Austria-Hungary. Countries like Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland stayed neutral. World War I pushed these powerful countries to their limits. Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire lost the war. Germany lost its status as a great power, and Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire broke apart into many smaller countries. The winning countries – Britain, France, Italy, and Japan – got permanent seats on the council of the new League of Nations. The United States was supposed to be the fifth permanent member, but it decided not to join the League.

Contents

- Europe After Napoleon: 1814–1830

- Travel, Trade, and Communication Changes

- Mid-1800s: 1830–1850s

- Nationalism and Unification: 1860–1871

- Transition Year: 1871

- Imperialism: Building Empires

- The Eastern Question

- Balkan Crises: 1908–1913

- The Coming of World War I

- The Great War: World War I

- Paris Peace Conference and Versailles Treaty: 1919

- See also

- Images for kids

Europe After Napoleon: 1814–1830

After Napoleon's power fell in 1814, the four main European powers – Britain, Prussia, Russia, and Austria – started planning for peace. They met at the Congress of Vienna in 1814–1815. They decided to create a German Confederation (which included Austria and Prussia), make French-controlled areas independent again, and bring back the old kings in Spain. They also made the Netherlands bigger to include what is now Belgium.

One main goal was to create a "balance of power". This meant making sure no single country or two countries became too strong. If one country gained land after a war, others might ask for "compensation" to keep things balanced. For example, after Prussia beat Austria in 1866, France was upset because it didn't get any land to balance Prussia's gains.

The Congress of Vienna: Keeping the Peace

The Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) ended the Napoleonic Wars and tried to bring back the kings Napoleon had removed. Leaders like Klemens von Metternich from Austria and Lord Castlereagh from Britain set up a system to keep the peace. This system, called the Concert of Europe, meant that the main European powers (Britain, Russia, Prussia, Austria, and later France) would meet regularly to solve problems. This was a new idea in Europe and aimed to manage European affairs peacefully. It was like an early version of the League of Nations and the United Nations.

Some historians say the Concert of Europe ended by 1823, while others believe it lasted through most of the 1800s. It helped keep the borders set at Vienna mostly unchanged until the 1860s. However, Britain decided in 1818 not to get involved in every European problem that didn't directly affect it. The system weakened as countries started to focus more on their own rivalries.

Britain's Foreign Policy Goals

George Canning (who was in charge of Britain's foreign policy from 1822 to 1827) wanted Britain to avoid getting too close to other powers. Britain had the strongest navy and was growing richer and more industrial. Its main foreign policy rule was that no single country should become too powerful in Europe. Britain also wanted to support the Ottoman Empire to stop Russia from expanding. It was against other countries trying to stop movements for liberal democracy. Canning worked with the United States to create the Monroe Doctrine. This policy aimed to protect the newly independent countries in Latin America from European control. Britain wanted to prevent France from dominating and to open up new markets for British businesses.

Ending the Slave Trade

A big step forward was stopping the international slave trade. Britain and the United States passed laws against it in 1807. The Royal Navy then patrolled around Africa to stop slave ships. Britain also made other countries agree to stop the trade. This greatly reduced the number of slaves brought from Africa to the Americas. Slavery was later ended in the British Empire in 1833, in France in 1848, in the United States in 1865, and in Brazil in 1888.

Spain Loses Its Colonies

Spain was at war with Britain from 1798 to 1808. The British Navy cut off Spain's connections with its colonies in the Americas. The colonies then set up their own temporary governments, becoming almost independent. There was a big split between Spaniards born in Spain (called peninsulares) and those of Spanish descent born in the Americas (called criollos). The criollos led the fight for independence and eventually won. Spain lost almost all its American colonies, except Cuba and Puerto Rico, between 1808 and 1826.

Britain and the United States worked against Spain, using the Monroe Doctrine to protect the new Latin American countries. British merchants and bankers became very important in Latin America. After losing its colonies, Spain became much less important in world affairs. Spain kept Cuba, but Cuba revolted many times. In 1898, the U.S. fought Spain in the Spanish–American War and won easily. The U.S. took Cuba (giving it partial independence) and also took the Philippines and Guam. Spain's role in international affairs was mostly over.

Greek Independence: 1821–1833

The Greek War of Independence was a major conflict in the 1820s. The powerful European countries supported the Greeks but didn't want the Ottoman Empire to be completely destroyed. Greece was first meant to be a self-governing state under the Ottomans. But by 1832, it was recognized as a fully independent kingdom.

The Ottoman Empire, with help from Egypt, brutally crushed the Greek rebellion. This angered people in Europe, including the English poet Lord Byron. Russia, which was expanding its power and supported the Orthodox Christian Greeks, saw this as an opportunity. Other European powers worried about Russia becoming too strong. Britain and France joined Russia in a treaty to help Greece become independent while trying to keep the Ottoman Empire mostly intact.

Their navies won a big victory at the Battle of Navarino in 1827, which greatly weakened the Ottomans. Greece was saved, but it took two more military actions – by Russia in 1828–29 and by France – to force the Ottomans out and secure Greek independence.

Travel, Trade, and Communication Changes

The world felt much smaller as travel and communication got much better. Every ten years, there were more ships, more places to go, faster trips, and cheaper prices for people and goods. This helped international trade and cooperation. After 1860, a huge increase in wheat farming in the United States sent prices down by 40% worldwide. This helped feed many poor people.

Faster Travel and Shipping

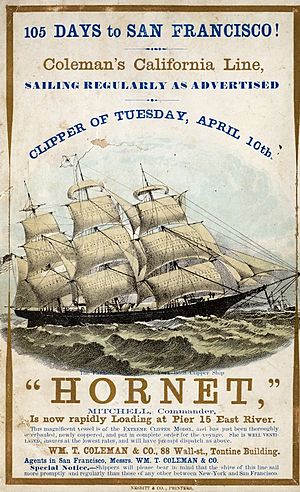

Old cargo ships were slow. The fastest sailing ships were "clippers" (1843–1869). They were narrow, carried less cargo, and had huge sails. They could go about six knots (about 7 miles per hour) and carried people across the world.

But the much faster steam-powered, iron-hulled ocean liner became the main way to travel from the 1850s to the 1950s. These ships used coal and needed many places to refuel. After 1900, oil replaced coal, making refueling easier.

Shipping costs stayed the same until about 1840, then dropped quickly. British shipping costs fell by 70% from 1840 to 1910. The Suez Canal, which opened in 1869, cut the travel time from London to India by a third. This meant ships could make more trips in a year, carrying more goods for less money.

Technology kept improving. Iron hulls replaced wood by the mid-1800s, and steel replaced iron after 1870. Steam engines slowly replaced sails. Wind was free, but coal was expensive and took up a lot of space. Early steam engines were not very efficient. By the 1860s, half of a ship's cargo space might be filled with coal. This was a big problem for warships. Only the British Empire had coaling stations all over the world for its navy. Later, better steam engines were built with steel, which could handle higher pressures. The steam turbine engine around 1907 made ships even more efficient.

Connecting the World with Telegraphs

By the 1850s, railways and telegraph lines connected all the major cities in Western Europe and the United States. The telegraph made travel easier to plan and replaced slow mail service. Underwater telegraph cables were laid to connect continents by the 1860s.

Mid-1800s: 1830–1850s

Britain remained the most powerful country, followed by Russia, France, Prussia, and Austria. The United States grew quickly in size, population, and economy, especially after beating Mexico in 1848. However, it avoided international problems because of its own internal issues, like slavery.

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was the only major war between the great powers. It was known for its many deaths and little long-term impact. Britain strengthened its colonies, especially in India. France built new colonies in Asia and North Africa. Russia continued to expand south and east. The Ottoman Empire kept getting weaker, losing control of parts of the Balkans to new countries like Greece and Serbia.

In the Treaty of London in 1839, the great powers promised to protect Belgium's neutrality. This became important in 1914 when Germany invaded Belgium to attack France, causing Britain to declare war on Germany.

Britain's Policies: Free Trade and Balance

Britain's decision in 1846 to remove taxes on food imports (called the Corn Laws) was a huge change. It made free trade Britain's main policy until the 1900s. This showed that industrial businesses had more power than farming interests.

From 1830 to 1865, Lord Palmerston largely guided Britain's foreign policy. He had six main goals:

- Protect British interests and prestige.

- Use the media to gain public support.

- Promote governments like Britain's, which had a constitution and more freedom.

- Support British nationalism.

- Avoid wars.

- Keep a balance of power to stop any one nation (especially France or Russia) from dominating Europe.

Palmerston worked with France when needed but didn't make permanent alliances. He tried to control powerful countries like Russia and Austria. He supported free governments because they brought more stability. But he also supported the autocratic Ottoman Empire because it stopped Russia from expanding.

Belgian Revolution

In 1830, Catholic Belgium broke away from the Protestant United Kingdom of the Netherlands and became an independent country. People in the south (mostly French-speaking Catholics) were against King William I's strict rule. There was fighting, but it took years for the Netherlands to accept defeat. In 1839, the Dutch signed the Treaty of London, accepting Belgium's independence. The major powers promised to protect Belgium.

Revolutions of 1848 Across Europe

The Revolutions of 1848 were a series of unorganized uprisings across Europe. People tried to overthrow old monarchies. This was the biggest wave of revolutions in European history, affecting over 50 countries. However, the old powers, especially with Russia's help, eventually won, and many rebels had to leave their countries. Still, some social changes happened.

These revolutions were mostly about getting more freedom and creating independent nations. They started in France in February. People wanted more say in government, freedom of the press, and better conditions for workers. Nationalism was also growing, with groups wanting their own united countries.

The uprisings were led by groups of reformers, middle-class people, and workers, but these groups didn't stay together for long. The revolutions started suddenly, catching the old rulers off guard. But the revolutionaries also weren't ready to hold power and often argued among themselves. The old rulers, with their wealth and strong connections, slowly regained control. Important lasting changes included ending serfdom in Austria and Hungary, ending absolute monarchy in Denmark, and starting representative democracy in the Netherlands.

The Ottoman Empire's Decline

The Ottoman Empire was only briefly involved in the Napoleonic Wars. It wasn't invited to the Vienna Conference. During this time, the Empire became weaker militarily and lost most of its land in Europe (like Greece) and North Africa (like Egypt). Its main enemy was Russia, while Britain was its main supporter.

As the 1800s went on, the Ottoman Empire grew weaker. It lost more control over local governments, especially in Europe. It borrowed a lot of money and went bankrupt in 1875. Britain became its main ally and protector, even fighting the Crimean War against Russia in the 1850s to help it survive.

Serbia Becomes Independent

A successful uprising against the Ottomans led to the creation of modern Serbia. The Serbian Revolution (1804–1835) changed this area from an Ottoman province into a country with its own constitution and a modern state. The first part of the revolution (1804–1815) was a violent fight for independence. The later part (1815–1835) saw Serbia slowly gain more self-rule. Serbian princes were recognized as hereditary rulers in 1830 and 1833, and the country grew in size. In 1835, Serbia adopted its first written constitution, which ended feudalism and serfdom.

The Crimean War

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was fought between Russia and an alliance of Great Britain, France, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire. Russia lost the war.

In 1851, France, led by Emperor Napoleon III, made the Ottoman government recognize France as the protector of Christian holy sites. Russia disagreed, saying it protected all Eastern Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire. France sent its navy to the Black Sea, and Russia responded with its own forces. In 1851, Russia sent troops into Ottoman provinces. Britain, worried about the Ottoman Empire, sent its fleet to join France, hoping Russia would back down. Diplomacy failed. The Ottoman Sultan declared war on Russia in October 1851. After an Ottoman naval defeat, Britain and France declared war on Russia. Most of the fighting happened in the Crimean peninsula.

Russia was defeated and signed the Treaty of Paris on March 30, 1856. The powerful countries promised to respect the Ottoman Empire's independence. Russia gave up some land and its claim to protect Christians in the Ottoman Empire. The Black Sea was made a neutral zone, and an international group was set up to ensure free trade on the Danube River.

The war helped modernize warfare by introducing railways, the telegraph, and modern nursing. It was a turning point for Russia, showing its army's weaknesses. Russia's weak economy couldn't support its military, so it focused on weaker Muslim areas in Central Asia and left Europe alone. The war weakened both Russia and Austria, which then allowed leaders like Napoleon III, Cavour (in Italy), and Otto von Bismarck (in Germany) to start a series of wars in the 1860s that changed Europe.

Moldavia and Wallachia Unite

The Ottoman areas of Moldavia and Wallachia slowly broke away from the Ottoman Empire. They united in 1859 to form what would become modern Romania, finally gaining full independence in 1878. These two areas had been under Ottoman control, but Russia and Austria also wanted them, making the region a place of conflict. The people were mostly Orthodox Christians and spoke Romanian.

With Russia's help, the Kingdom of Romania officially became independent in 1878. It then focused on Transylvania, a region historically part of Hungary but with many Romanians. When the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed after World War I, Romania united with Transylvania.

United States Defeats Mexico, 1846–1848

Mexico refused to accept the U.S. annexation of Texas in 1845. Mexico still saw Texas as its territory. The U.S. declared war in May 1846 after the Mexican Army attacked U.S. forces. The United States Army quickly took control of New Mexico and California and invaded northern Mexico. In March 1847, the U.S. Navy and Marines attacked Veracruz, Mexico's largest port. By September, U.S. forces had captured Mexico City.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in January 1848, ending the war. Mexico recognized Texas as a U.S. state and gave up its northern territories to the U.S. for $15 million. The U.S. also agreed to pay $3.25 million in Mexican debt. In total, Mexico gave up about 55% of its land claims to the United States.

Brazil and Argentina

Brazil became independent from Portugal in 1822. It faced pressure from Britain to end its involvement in the slave trade. Brazil fought wars in the La Plata river region, including the Cisplatine War against Argentina (1828) and the Platine War with Argentina (1850s). The Paraguayan War (1860s) saw Argentina and Brazil allied against Paraguay. This was the bloodiest and most expensive war in South American history, almost destroying Paraguay. After this, Brazil and Argentina entered a peaceful period, avoiding foreign conflicts.

Nationalism and Unification: 1860–1871

Nationalism grew hugely in the 1800s. It was a feeling of shared cultural identity among people with the same language and history. It was strong in existing countries and pushed for unity or independence among Germans, Irish, Italians, Greeks, and Slavic peoples. This strong sense of nationalism also grew in independent nations like Britain and France.

Great Britain's Neutrality

In 1859, Lord Palmerston became Prime Minister again, with Earl Russell as Foreign Secretary. This was a busy time, with Italy uniting, the American Civil War, and a war in 1864 over Schleswig-Holstein. Russell and Palmerston considered helping the Southern states in the American Civil War but kept Britain neutral in all these conflicts.

France's Foreign Policy Under Napoleon III

Despite promising peace, Napoleon III couldn't resist seeking glory in foreign affairs. He was a poor diplomat and often upset his own supporters. France and Britain worked together in the 1850s, fighting in the Crimean War and signing a trade treaty in 1860. However, Britain grew to distrust France, especially as Napoleon built up his navy and expanded his empire.

Napoleon III had some successes: he strengthened French control over Algeria, set up bases in Africa, began taking over Indochina, and opened trade with China. He also helped a French company build the Suez Canal. But in Europe, Napoleon failed repeatedly. The Crimean War brought no gains. A war with Austria in 1859 helped Italy unite, and France gained Savoy and Nice. But his actions often angered different groups, and his attempt to control Mexico (1861–1867) was a disaster.

Finally, he went to war with Prussia in 1870, too late to stop Germany from uniting. Napoleon had no allies and France was divided. France was badly defeated in the Franco-Prussian War, losing Alsace–Lorraine. Historians say he "ruined France as a great power."

Italian Unification

The Risorgimento was the time from 1848 to 1871 when Italians gained independence from Austrian rulers in the north and Spanish rulers in the south, uniting Italy. Piedmont (also called the Kingdom of Sardinia) led this effort and applied its constitutional system to the new country.

The Pope, who ruled the Papal States, got French support to resist unification. He feared losing control would weaken the Catholic Church. The Kingdom of Italy finally took over the Papal States in 1870 when the French Army left. The angry Pope Pius IX declared himself a "prisoner." His successor, Pope Pius XI, finally made peace with Italy in 1929. After 1870, Italy was recognized as the sixth great power, though it was weaker than the others.

United States Civil War Diplomacy

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), the Southern states tried to break away and form the Confederate States of America. The North fought to keep the country united. British and French leaders, who disliked American democracy, favored the Confederacy. The South was also the main source of cotton for European factories. The Confederacy hoped Britain and France would join the war against the North. They believed "cotton is king," meaning cotton was so important that Europe would fight for it.

However, Britain had a lot of cotton in 1861, and shortages didn't happen until 1862. More importantly, Britain depended on grain from the U.S. North for much of its food. France wouldn't intervene alone and was more interested in controlling Mexico than cotton. Washington made it clear that recognizing the Confederacy meant war with the U.S.

In September 1862, President Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in the rebellious states. This meant supporting the Confederacy would mean supporting slavery, so European intervention became impossible.

However, some British companies built fast ships to smuggle weapons to the Confederacy. They also secretly built warships for the Confederacy. These ships caused a big diplomatic problem. In 1872, an international court ruled that Britain had to pay the U.S. $15.5 million for damages caused by these British-built Confederate warships.

Germany's Unification

The Kingdom of Prussia, led by Otto von Bismarck, united all of Germany (except Austria) and created a new German Empire with the Prussian king as its head. To do this, Bismarck fought short, decisive wars with Denmark, Austria, and France. The smaller German states followed Prussia's lead. After defeating France in 1871, they all united. Bismarck's Germany then became the most powerful country in Europe, and he worked to keep peace for decades.

Schleswig and Holstein Conflicts

A big diplomatic problem and several wars came from the complicated situation in Schleswig and Holstein. Danish and German claims clashed, and Austria and France got involved. These two areas were ruled by the king of Denmark but were not legally part of Denmark. An international treaty said they couldn't be separated. In the 1840s, as nationalism grew, Denmark tried to make Schleswig part of its kingdom. The first war was a Danish victory. But in the Second Schleswig War of 1864, Denmark was defeated by Prussia and Austria.

German Unification Wars

Berlin and Vienna split control of the two areas. This led to conflict between them, solved by the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. Prussia won quickly, becoming the leader of German-speaking peoples. Austria then became less important among the great powers. Emperor Napoleon III of France couldn't accept Prussia's rapid rise and started the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 over small issues. German nationalism caused the smaller German states to join Prussia. The German side won easily, making France a less powerful country. Prussia, under Bismarck, then united almost all German states (except Austria) into a new German Empire. Bismarck's new empire was the strongest in mainland Europe until 1914.

Transition Year: 1871

Keeping the Peace in Europe

After 15 years of wars, Europe entered a period of peace in 1871. With the creation of the German Empire, Otto von Bismarck became a very important figure in European history from 1871 to 1890. He controlled Prussia and the new German Empire's foreign and domestic policies. Bismarck, who had been known for making wars, suddenly became a peacemaker. He cleverly used the balance of power to keep Germany strong and Europe peaceful. Historians say Bismarck was the "undisputed world champion" of diplomacy for almost 20 years after 1871, working only to keep peace between the powers.

Bismarck's main mistake was giving in to the army and public demand to take the border regions of Alsace and Lorraine from France. This made France a permanent enemy. France wanted revenge and to get Alsace-Lorraine back for the next 40 years. Bismarck's solution was to make France an isolated country. He built complex alliances with Austria, Russia, and Britain to keep France alone. A key part was the League of the Three Emperors, where the rulers of Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary promised to protect each other and keep France out. This alliance lasted from 1881 to 1887.

Major Powers and Their Policies

Britain entered an era of "splendid isolation", avoiding problems that had led it into the Crimean War. It focused on its own industry, political changes, and building its huge British Empire. It kept the world's strongest navy to protect its home and colonies. Russia used the Franco-Prussian War to cancel the 1856 treaty that had forced it to remove its military from the Black Sea. This was a big deal, but a conference in London in 1871 formally allowed Russia's action. Russia always wanted control of Constantinople and the Turkish Straits (which connect the Black Sea to the Mediterranean).

France had kept an army in Rome to protect the Pope. When these soldiers were called back in 1870, the Kingdom of Italy moved in, took the remaining papal lands, and made Rome its capital in 1871. Italy was finally united, but this angered the Pope and Catholics for half a century. The situation was finally resolved in 1929.

Conscription: Armies Grow Huge

A big change was the move from small professional armies to a system like Prussia's. This system had a core of career soldiers, plus many young men who served for a year or two, then moved into the reserves for a decade or more, with yearly summer training. This meant a much larger, well-trained army could be quickly called up in wartime. Prussia started this in 1814, and its victories in the 1860s made other countries adopt it.

The main idea was universal conscription, meaning almost all young men had to serve. Austria adopted it in 1868, France in 1872, Japan in 1873, Russia in 1874, and Italy in 1875. By 1900, all major countries except Britain and the United States had conscription. By then, Germany had a peacetime army of 545,000, which could quickly grow to 3.4 million with reserves. This new system was expensive, with costs doubling or tripling between 1870 and 1914.

Imperialism: Building Empires

Most major powers (and some smaller ones like Belgium and the Netherlands) engaged in imperialism, building huge empires, especially in Africa and Asia. Although there were many uprisings, there were only a few small wars: the First Boer War (1880–1881), Second Boer War (1899–1902), First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), First Italo-Ethiopian War (1895–1896), Spanish–American War (1898), Philippine–American War (1899-1902), and Italo-Ottoman war (1911). The biggest was the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, the only one where two major powers fought each other.

Historians have different views on how profitable these empires were. The idea was that colonies would be good markets for manufactured goods. But this was rarely true, except for India. By the 1890s, empires mainly provided cheap raw materials for factories back home. Great Britain made good money from India but not much from most of its other colonies. The Netherlands did very well from its colonies in the East Indies. Germany and Italy got very little trade or raw materials from their empires. France did a bit better. The Congo Free State was very profitable for King Leopold II of Belgium as his private rubber plantation. But scandals about badly treated workers forced the Belgian government to take it over in 1908, and it became much less profitable.

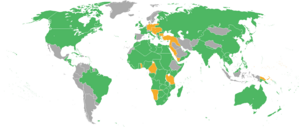

By World War I, the world's colonial population was about 560 million people. Most (70%) were in British areas, 10% in French, and smaller percentages in Dutch, Japanese, German, American, Portuguese, Belgian, and Italian colonies.

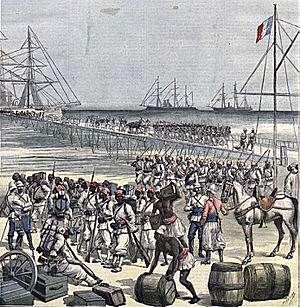

France's Empire in Asia and Africa

France Tries to Control Mexico

Napoleon III tried to take control of Mexico during the American Civil War and put his own emperor, Maximilian I of Mexico, in charge. France, Spain, and Britain sent forces to Mexico in 1861 because of unpaid debts. Spain and Britain soon left when they realized Napoleon III wanted to overthrow the Mexican government and create an empire. Napoleon had the support of some Mexican conservatives. In 1862, he installed Austrian archduke Maximilian as Emperor of Mexico.

But the Mexican president, Benito Juárez, fought back. Washington supported Juárez and refused to recognize the new government because it broke the Monroe Doctrine. After winning its Civil War in 1865, the U.S. sent 50,000 troops to the Mexican border to show its disapproval. Napoleon had too many troops spread out in Mexico, Rome, and Algeria. Also, Prussia was a growing threat. Napoleon realized his mistake and pulled all his forces out of Mexico in 1866. Juárez regained control and executed the emperor.

The Suez Canal, built by a French company, became a joint British-French project in 1875. Both countries saw it as vital for their empires in Asia. In 1882, unrest in Egypt led Britain to intervene, taking effective control of Egypt. France, whose leader Jules Ferry was out of office, allowed Britain to do this.

Britain Takes Over Egypt, 1882

The most important event was the Anglo-Egyptian War, which led to Britain controlling Egypt for 70 years. The Ottoman Empire still technically owned Egypt until 1914. France was very unhappy, having lost control of the canal it built and financed. Germany, Austria, Russia, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire were all angered by Britain's solo action. Historians call this a "great event" that changed the balance of power.

Britain's control of Egypt secured its route to India and made it a master of the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone and his Liberal Party were usually against imperialism. Historians debate why he suddenly changed policy. Many argue it was an urgent need to protect the Suez Canal from chaos and a nationalist revolt that threatened international trade and the British Empire. A full takeover of Egypt would have been too risky, possibly leading to a major war as other powers rushed to grab parts of the weakening Ottoman Empire.

The Great Game in Central Asia: Britain vs. Russia

The "Great Game" was a political and diplomatic struggle between Britain and Russia for most of the 1800s. It was about who would control Afghanistan and nearby areas in Central and Southern Asia, especially Persia (Iran) and Turkestan. Britain wanted to protect all routes to India. Russia, though it couldn't directly invade India, made plans that Britain found believable. Both powers tried to expand their colonies in Inner Asia. This created a lot of distrust and a constant threat of war between the two empires. There were many local conflicts, but a direct war between Britain and Russia in Central Asia never happened.

Bismarck knew that both Russia and Britain cared a lot about Central Asia. Germany had no direct interest there, but its power in Europe grew when Russian troops were far away. From 1871 to 1890, he tried to help Britain, hoping Russia would send more soldiers to Asia. However, through the League of the Three Emperors, Bismarck also helped Russia by pressuring the Ottoman Empire to block British naval access to the Bosporus.

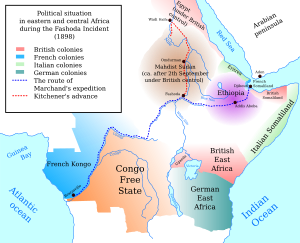

The Scramble for Africa

The "Scramble for Africa" began when Britain unexpectedly took over Egypt in 1882. This led to a free-for-all as Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Portugal all greatly expanded their empires in Africa. The King of Belgium personally controlled the Congo. Coastal bases became the starting points for colonies that stretched inland.

In the 1900s, the Scramble for Africa was criticized by those against imperialism. But at the time, it was seen as a way to stop the terrible violence caused by uncontrolled adventurers and slave traders. Bismarck tried to bring order by holding the Berlin Conference in 1884–1885. All European powers agreed on rules to avoid conflicts in Africa.

In British colonies, workers and businessmen from India were brought in to build railways, farms, and other businesses. Britain used its experience from India to manage Egypt and other new African colonies.

Tensions between Britain and France grew high in Africa. War was possible several times but never happened. The most serious event was the Fashoda Incident of 1898. French troops tried to claim an area in Southern Sudan, but a British force arrived to confront them. Under pressure, the French left, giving Britain and Egypt control of the area. This was a big disappointment for France.

The Ottoman Empire lost its control over Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. It only had nominal control of Egypt. In 1875, Britain bought the Suez Canal shares from the nearly bankrupt Egyptian ruler.

Kenya's Colonization

Kenya's story shows how East Africa was colonized. By 1850, European explorers were mapping the interior. Three things increased European interest in East Africa:

- The island of Zanzibar became a base for trade and exploration of the African mainland.

- Europeans wanted more African products like ivory and cloves.

- Britain wanted to stop the slave trade. Later, German competition also made Britain more interested.

In 1887, a British company leased a strip of land along the coast from the Sultan of Zanzibar. Germany set up a protectorate over the Sultan's coastal areas in 1885. In 1890, Germany traded its coastal lands to Britain in exchange for control over the coast of Tanganyika (now Tanzania).

In 1895, the British government claimed the interior of Kenya and set up the East Africa Protectorate. This area was expanded in 1902 and became a British colony in 1920. With colonial rule, the Rift Valley and Highlands became a place for white immigrants to set up large coffee farms, using mostly Kikuyu labor. There were no significant minerals like gold or diamonds.

A key to developing Kenya's interior was building a railway from Mombasa to Lake Victoria, started in 1895 and finished in 1901. About 32,000 workers were brought from British India for the manual labor. Many stayed, as did Indian traders and small businessmen who saw opportunities in Kenya.

Portugal's Empire

The Kingdom of Portugal, a small, poor farming nation with a strong history of seafaring, built a large empire. It kept its empire longer than others by avoiding wars and staying mostly under Britain's protection. In 1899, it renewed its old treaty with Britain from 1386.

Portugal's explorations in the 1500s led to a colony in Brazil. Portugal also set up trading posts in Africa, South Asia, and East Asia. Portugal had used slaves in its own country and became a major slave trading nation. Portuguese businessmen set up slave plantations on nearby islands like Madeira and Cape Verde, focusing on sugar. In 1770, a leader named Pombal declared trade a noble profession, allowing businessmen to join the Portuguese upper class. Many settlers moved to Brazil, which became independent in 1822.

After 1815, Lisbon kept its trading ports along the African coast, moving inland to control Angola and Mozambique. The slave trade was ended in 1836. In India, trade grew in the colony of Goa, with its smaller colonies of Macau (near Hong Kong) and Timor (north of Australia). The Portuguese successfully brought Catholicism and the Portuguese language to their colonies.

Italy's Imperial Ambitions

Italy was often called the "least of the great powers" because of its weak industry and military. In the Scramble for Africa in the 1880s, Italy's new leaders wanted colonies in Africa. They hoped this would make Italy seem more powerful and help unite its people. In North Africa, Italy first looked at Tunis, which was under Ottoman control and where many Italian farmers lived. But Italy was weak and isolated, so it was helpless and angry when France took control of Tunis in 1881.

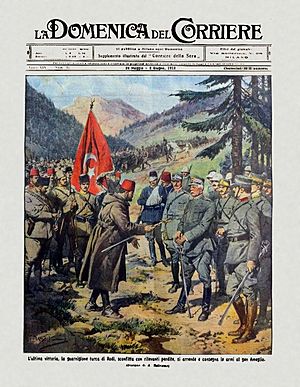

Italy then turned to East Africa and tried to conquer the independent Ethiopian Empire. But it was badly defeated at the Battle of Adwa in 1896. Public opinion was angry about this national humiliation. In 1911, the Italian people supported taking over what is now Libya.

Italian diplomacy over 20 years managed to get permission from Germany, France, Austria, Britain, and Russia to take Libya. In the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–12, the Italian army took control of a few coastal cities against strong resistance from the Ottoman army and local tribes. After the peace treaty gave Italy control, it sent Italian settlers but suffered many deaths in its brutal campaign against the tribes.

Japan's Rise to Power

Starting in the 1860s, Japan quickly modernized like Western countries. It built industries, government systems, and a strong military. This allowed it to expand its empire into Korea, China, Taiwan, and southern islands. Japan felt it needed to control nearby areas to protect itself from aggressive Western imperialism. It took control of Okinawa and Formosa (Taiwan). Japan's desire to control Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria led to the First Sino-Japanese War with China in 1894–1895 and the Russo-Japanese War with Russia in 1904–1905. The war with China made Japan the first modern imperial power from the East. The war with Russia showed that an Eastern power could defeat a Western one. After these wars, Japan became the dominant power in the Far East, controlling southern Manchuria and Korea (which it officially took over in 1910).

Okinawa

Okinawa island is the largest of the Ryukyu Islands. It paid tribute to China from the late 1300s. Japan took control of all the Ryukyu islands in 1609 and officially made them part of Japan in 1879.

War with China

Friction between China and Japan grew from the 1870s over Japan's control of the Ryukyu Islands, competition for influence in Korea, and trade issues. Japan, with its stable political and economic system and a modern, well-trained army and navy, easily defeated China in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894. Japanese soldiers killed many Chinese after capturing Port Arthur. In the harsh Treaty of Shimonoseki in April 1895, China recognized Korea's independence and gave Taiwan, the Penghu Islands, and the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan. China also had to pay Japan a large sum of money, open five new ports for international trade, and allow foreign companies (including Japanese and Western ones) to build factories in these cities.

However, Russia, France, and Germany felt disadvantaged by the treaty. In the Triple Intervention, they forced Japan to return the Liaodong Peninsula in exchange for more money. The only good thing for China was that these factories helped industrialize its cities, creating a local class of business owners and skilled workers.

Taiwan

Taiwan (Formosa) had native people when Dutch traders arrived in 1623, needing a base to trade with Japan and China. The Dutch soon ruled the natives. China took control in the 1660s and sent settlers. By the 1890s, there were about 2.3 million Han Chinese and 200,000 native people. After Japan's victory in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894–95, the peace treaty gave the island to Japan. It was Japan's first colony.

Japan expected more benefits from Taiwan than it got. Japan knew its home islands had limited resources and hoped Taiwan, with its fertile farmlands, would help. By 1905, Taiwan produced rice and sugar and paid for itself. More importantly, Japan gained prestige in Asia for being the first non-European country to run a modern colony. It learned how to adapt its German-based government rules to local conditions and how to deal with frequent uprisings. Japan aimed to promote its language and culture but realized it first had to adapt to the Chinese culture of the people. Japan opened schools to make peasants productive and patriotic workers. Medical facilities were modernized, and death rates dropped. To keep order, Japan set up a police state that watched the people closely. Taiwan was meant to eventually become part of Japan. When Japan surrendered in 1945, it lost its empire, and Taiwan was returned to China after over 50 years of Japanese rule.

Japan Defeats Russia, 1904–1905

Japan felt humiliated when the Western Powers (including Russia) partly reversed the gains from its victory over China. In the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), Japan and Russia were allies fighting against the Chinese. In the 1890s, Japan was angry about Russia expanding into its plans for influence in Korea and Manchuria. Japan offered to recognize Russia's control in Manchuria if Russia recognized Korea as part of Japan's influence. Russia refused and demanded Korea north of the 39th parallel be a neutral zone. Japan decided to go to war to stop Russia's threat to its expansion plans. The Japanese Navy started by attacking the Russian fleet at Port Arthur, China, by surprise. Russia suffered many defeats, but Tsar Nicholas II kept fighting, hoping for naval victories. When that didn't happen, he fought to save Russia's dignity. Japan's complete military victory surprised the world. It changed the balance of power in East Asia and showed Japan's new importance on the world stage. It was the first major modern military victory of an Asian power over a European one.

Korea

In 1905, Japan and Korea signed a treaty that made Korea a Japanese protectorate. This was a result of Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War and its desire to control the Korean Peninsula. Two years later, the 1907 Treaty made sure Korea would follow a Japanese resident general and that Japan would control Korea's internal affairs. Korean Emperor Gojong was forced to step down because he protested Japan's actions. Finally, in 1910, the Annexation Treaty officially made Korea part of Japan.

Dividing Up China

After losing wars to Britain, France, and Japan, China remained a unified country in name. But in reality, European powers and Japan took control of certain port cities and surrounding areas from the mid-1800s until the 1920s. They used "extraterritoriality" (meaning their citizens were not subject to Chinese laws) which was forced on China through a series of "unequal treaties."

In 1899–1900, the United States gained international acceptance for the Open Door Policy. This policy meant that all nations would have access to Chinese ports, rather than just one nation controlling them.

Britain's Foreign Policies

Free Trade Imperialism

Britain not only took control of new lands but also gained huge economic and financial power in many independent countries, especially in Latin America and Asia. It lent money, built railways, and traded. The Great Exhibition in London in 1851 clearly showed Britain's lead in engineering, communication, and industry. This lasted until the United States and Germany grew stronger in the 1890s.

Splendid Isolation

Historians agree that Lord Salisbury, as foreign minister and prime minister (1885–1902), was a strong and effective leader in foreign affairs. He understood Britain's interests very well. He oversaw the division of Africa, the rise of Germany and the U.S. as imperial powers, and Britain's shift of attention from the Dardanelles to Suez, all without causing a major war between the great powers. From 1886 to 1902, Britain continued its policy of "Splendid isolation", meaning it had no formal allies. Lord Salisbury became less comfortable with this term in the 1890s, especially as France formed an alliance with Russia.

Policy Toward Germany

Britain and Germany tried to improve relations, but British distrust of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany was deep because of his reckless actions. The Kaiser did interfere in Africa to support the Boers, which hurt relations.

Their main achievement was a friendly treaty in 1890. Germany gave up its small Zanzibar colony in Africa and gained the Heligoland islands, which were important for Germany's ports. Other attempts at friendship failed, and a big Anglo-German naval arms race (1880s-1910s) made tensions worse.

Liberal Party Splits on Imperialism

After 1880, the Liberal Party's policy was shaped by William Ewart Gladstone, who often attacked Disraeli's imperialism. The Conservatives were proud of their imperialism, and it was popular with voters. A generation later, a small group of Liberals became "Liberal Imperialists." The Second Boer War (1899–1902) was fought by Britain against two independent Boer republics. After a long, hard war, the Boers lost and became part of the British Empire. The war deeply divided the Liberals, with most of them criticizing it. Joseph Chamberlain and his followers left the Liberal Party and allied with the Conservatives to promote imperialism.

The Eastern Question

The Eastern Question from 1870 to 1914 was about the risk of the Ottoman Empire falling apart. Attention focused on growing nationalism among Christian groups in the Balkans, especially with Serbia's support. This risked major conflicts between Austria-Hungary and Russia, and between Russia and Great Britain. Russia especially wanted control of Constantinople and the straits connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. British policy had long been to support the Ottoman Empire against Russia. However, in 1876, William Gladstone highlighted Ottoman cruelties against Christians in Bulgaria. These cruelties, along with Ottoman attacks on Armenians and Russian attacks on Jews, drew public attention across Europe and made peaceful solutions harder.

Long-Term Goals of the Powers

Each country focused on its own long-term interests, usually working with allies.

Ottoman Empire (Turkey)

The Ottoman Empire was under pressure from nationalist movements among its Christian populations and was behind in modern technology. After 1900, the large Arab population also became nationalistic. The threat of the empire breaking apart was real. Egypt, for example, had been independent for a century, though still technically part of the Ottoman Empire. Turkish nationalists emerged, and the Young Turk movement took over the Empire. While previous rulers had allowed many different groups, the Young Turks were hostile to other nationalities and non-Muslims. Wars usually ended in defeat, with more territory being lost and becoming semi-independent, including Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Romania, Bosnia, and Albania.

Austro-Hungarian Empire

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, based in Vienna, was a mostly rural, poor, multicultural state. It was run by the Habsburg family, who demanded loyalty to the throne, not to a nation. Nationalist movements were growing fast. The most powerful were the Hungarians, who kept their separate status within the empire. Other minority groups were very frustrated. German nationalists, especially in Bohemia, looked to Berlin in the new German Empire. There was a small German-speaking Austrian group around Vienna, but they didn't push for an independent state. Instead, they held most of the high military and diplomatic jobs in the Empire. Russia was the main enemy, as were Slavic nationalist groups inside the Empire (especially in Bosnia-Herzegovina) and in nearby Serbia. Austria, Germany, and Italy had a defensive military alliance (the Triple Alliance), but Italy was unhappy and wanted some territory controlled by Vienna.

Russia's Ambitions

Russia was growing stronger and wanted access to the warm waters of the Mediterranean Sea. To do this, it needed control of the Straits, which connect the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, and possibly control of Constantinople, the Ottoman capital. Slavic nationalism was rising strongly in the Balkans, giving Russia a chance to protect Slavic and Orthodox Christians. This put Russia in strong opposition to the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Serbia's Goals

The Kingdom of Serbia had several national goals. Serbian thinkers dreamed of a South Slavic state, which became Yugoslavia in the 1920s. Many Serbs living in Bosnia looked to Serbia as the center of their nationalism, but they were ruled by the Austrian Empire. Austria's takeover of Bosnia in 1908 deeply angered the Serbs. Plotters swore revenge, which they got in 1914 by assassinating the Austrian heir. Serbia was landlocked and badly needed access to the Mediterranean, preferably through the Adriatic Sea. Austria worked hard to block Serbia's access, for example, by helping create Albania in 1912. Serbia's main ally, Montenegro, had a small port, but Austrian territory blocked access until Serbia gained land from the Ottoman Empire in 1913. To the south, Bulgaria blocked Serbia's access to the Aegean Sea.

Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, and Bulgaria formed the Balkan League and went to war with the Ottomans in 1912–1913. They won decisively and drove the Ottoman Empire out of almost all the Balkans. The main remaining enemy was Austria, which strongly rejected Pan-Slavism and Serbian nationalism and was ready to go to war to stop these threats. Serbia relied mostly on Russia for support, but Russia was hesitant at first. However, in 1914, Russia changed its mind and promised military support to Serbia.

Germany's Balkan Policy

Germany had no direct involvement in the Balkans, but Bismarck knew it was a major source of tension between his two key allies, Russia and Austria. So, Germany's policy was to reduce conflict in the Balkans.

Great Eastern Crisis of 1875–1878: Turkey at War

In 1876, Serbia and Montenegro declared war on Turkey and were badly defeated. William Gladstone published an angry pamphlet about "The Bulgarian Horrors," which caused huge public anger in Britain against Turkish misrule. This made it harder for the British government to support Turkey against Russia. Russia, which supported Serbia, threatened war against Turkey. In August 1877, Russia declared war on Turkey and steadily defeated its armies. In early 1878, Turkey asked for a ceasefire. Russia and Turkey signed the Treaty of San Stefano on March 3, which greatly favored Russia, Serbia, Montenegro, Romania, and Bulgaria.

Congress of Berlin

Britain, France, and Austria opposed the Treaty of San Stefano because it gave Russia and Bulgaria too much power in the Balkans. War seemed likely. After many attempts, a big diplomatic agreement was reached at the Congress of Berlin (June–July 1878). Germany's Chancellor Otto von Bismarck led the congress and helped create compromises. The new Treaty of Berlin changed the earlier treaty. The Congress ended the strong ties between Germany and Russia, making them military rivals. The clear weakness of the Ottoman Empire encouraged Balkan nationalism and made Vienna a major player in Balkan politics. In 1879, Bismarck solidified the new power balance by creating an alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary.

When borders were drawn, keeping ethnic groups together was not a priority, which created new problems between nationalistic groups. One result was that Austria took control of Bosnia and Herzegovina, planning to eventually make them part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Bosnia was finally annexed by Austria-Hungary in 1908, which angered Serbs. Bosnian Serbs assassinated Austria's heir, Franz Ferdinand, in 1914, leading to World War I.

Minority Rights

The 1878 Treaty of Berlin had new rules that protected minorities in the Balkans and newly independent states. Great Power recognition was given if these states promised to protect religious and civic freedoms for local religious minorities. However, these rules were generally not enforced because there was no good way to do so, and the Great Powers weren't very interested. These protections became more important after World War II.

Britain's Policies: Aloofness and Morality

Britain stayed out of alliances in the late 1800s. This was possible because it was an island, had the strongest navy, was dominant in finance and trade, and had a strong industrial base. It rejected tariffs and practiced free trade. After losing power in 1874, Liberal leader Gladstone returned in 1876, calling for a moral foreign policy, unlike his rival Benjamin Disraeli's realism. This issue divided the Liberal Party (who criticized the Ottomans) and the Conservative Party (who supported the Ottomans against Russia).

Gladstone's "Midlothian campaign" in 1880 charged Disraeli's government with financial mistakes and poor foreign policy. Gladstone felt a call from God to help the Serbians and Bulgarians (who were Eastern Orthodox Christians). He spoke out against tyranny. By appealing to large audiences and criticizing Disraeli's pro-Turkish policy, Gladstone became a moral force in Europe, united his party, and returned to power.

German Policy, 1870–1890

Chancellor Bismarck fully controlled German foreign policy from 1870 until he was fired in 1890. His goal was a peaceful Europe based on the balance of power, with Germany at the center. His policy was successful. Germany had the strongest economy and military in mainland Europe. Bismarck made it clear that Germany did not want more territory in Europe and tried to stop German colonial expansion. Bismarck feared that Austria, France, and Russia could combine against Germany. His solution was to ally with two of the three. In 1873, he formed the League of the Three Emperors, an alliance of the German, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian emperors. This protected Germany from a war with France. The three emperors could control Central and Eastern Europe, keeping restless ethnic groups like the Poles in check. The Balkans were a bigger problem, and Bismarck's solution was to give Austria power in the west and Russia power in the east. The system fell apart in 1887. Kaiser Wilhelm fired Bismarck in 1890 and developed his own aggressive foreign policy. The Kaiser ended the alliance with Russia, and Russia then allied with France.

"War in Sight" Crisis of 1875

Between 1873 and 1877, Germany often interfered in the internal affairs of France's neighbors. In Belgium, Spain, and Italy, Bismarck strongly pushed for liberal, anti-church governments. This was part of a plan to encourage a republic in France by isolating the royalist government of President MacMahon. It was hoped that surrounding France with liberal states would help French republicans defeat MacMahon.

This policy almost got out of hand in 1875 during the "War in Sight" crisis. A Berlin newspaper article, "Krieg-in-Sicht" (War in Sight), suggested that powerful Germans, worried about France's quick recovery and rearmament, were talking about starting a preventive war against France to keep it down. There was a war scare in Germany and France. Britain and Russia made it clear they would not allow a preventive war. Bismarck didn't want war either, but the crisis made him realize how much fear and alarm his bullying and Germany's fast growth were causing. This made Bismarck determined to actively work for peace in Europe, rather than just reacting to events.

Russia and France Become Allies, 1894–1914

A key change in Russian foreign policy was moving away from Germany and toward France. This happened in 1890 when Bismarck was fired, and Germany refused to renew a secret treaty with Russia. This encouraged Russia to expand into Bulgaria and the Straits. It meant both France and Russia were without major allies. France took the lead, funding Russia's economy and exploring a military alliance. Russia had never been friendly with France, remembering the Crimean War and Napoleon's invasion. It saw republican France as a dangerous source of rebellion against Russia's absolute monarchy.

France, which Bismarck had isolated, decided to improve relations with Russia. It lent money to Russia, increased trade, and started selling warships after 1890. After Bismarck left office in 1890, the treaty between Russia and Germany was not renewed. German bankers stopped lending to Russia, which increasingly relied on French banks.

In 1894, a secret treaty said Russia would help France if Germany attacked France. It also said that in a war against Germany, France would quickly mobilize 1.3 million men, and Russia would mobilize 700,000 to 800,000. If any of the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria, Italy) mobilized its reserves, both Russia and France would mobilize theirs. This set the stage for the start of World War I in July 1914.

Historian George F. Kennan argues that Russia was mainly responsible for the breakdown of Bismarck's alliance policy and the start of the path to World War I. Kennan blames poor Russian diplomacy focused on its goals in the Balkans. He says Bismarck's foreign policy aimed to prevent any major war. Russia left Bismarck's Three Emperors' League and instead allied with France.

Balkan Crises: 1908–1913

Bosnian Crisis of 1908–1909

The Bosnian Crisis began on October 8, 1908, when Vienna announced it was taking over Bosnia and Herzegovina. These areas were technically part of the Ottoman Empire but had been managed by Austria-Hungary since 1878. This action, timed with Bulgaria's declaration of independence from the Ottoman Empire, caused protests from all the Great Powers, especially Serbia and Montenegro. In April 1909, the Treaty of Berlin was changed to accept the takeover, ending the crisis.

The crisis permanently damaged relations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, Italy, and Russia. At the time, it seemed like a complete diplomatic victory for Vienna. But Russia became determined not to back down again and sped up its military build-up. Austrian-Serbian relations became very tense. It caused intense anger among Serbian nationalists, which led to the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in 1914.

Balkan Wars

The continued weakening of the Ottoman Empire led to two wars in the Balkans in 1912 and 1913, which were a preview of World War I. By 1900, independent nations had formed in Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, and Serbia. However, many of their ethnic relatives still lived under Ottoman control. In 1912, these countries formed the Balkan League. There were three main reasons for the First Balkan War:

- The Ottoman Empire couldn't reform itself or govern its diverse peoples well.

- The Great Powers argued among themselves and failed to make the Ottomans carry out reforms. This led the Balkan states to act on their own.

- The Balkan League members were confident they could defeat the Turks. They were right; the Ottomans asked for peace after six weeks of fighting.

The First Balkan War started when the League attacked the Ottoman Empire on October 8, 1912. It ended seven months later with the Treaty of London. After five centuries, the Ottoman Empire lost almost all its land in the Balkans. The Great Powers imposed the treaty, and the victorious Balkan states were unhappy with it. Bulgaria was unhappy about how Macedonia was divided, which its former allies, Serbia and Greece, had done secretly. Bulgaria attacked to force them out of Macedonia, starting the Second Balkan War. The Serbian and Greek armies pushed back the Bulgarian attack and counter-attacked into Bulgaria. Romania and the Ottoman Empire also attacked Bulgaria and gained (or regained) territory. In the resulting Treaty of Bucharest, Bulgaria lost most of the land it had gained in the First Balkan War.

The long-term result was increased tension in the Balkans. Relations between Austria and Serbia became very bitter. Russia felt humiliated after Austria and Germany stopped it from helping Serbia. Bulgaria and Turkey were also unhappy and eventually joined Austria and Germany in World War I.

The Coming of World War I

Many factors led to World War I, which started unexpectedly in central Europe in summer 1914. These included conflicts and hostility from the four decades before the war. Militarism (building up armies), alliances, imperialism, and ethnic nationalism all played big roles. However, the immediate cause of the war was the decisions made by leaders and generals during the Crisis of 1914. This crisis began with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (the heir to Austria-Hungary's throne) by a Serbian secret group called the Black Hand.

Germany Fears Being Surrounded

Germany worried about being "encircled" by its enemies. There was a growing fear in Berlin that the supposed enemy group of Russia, France, and Britain was getting stronger militarily each year, especially Russia. Germany believed that the longer it waited, the less likely it would win a war. Few outside observers agreed that Germany was a victim of deliberate encirclement.

Mobilizing Armies for War

By the 1870s or 1880s, all major powers were preparing for a large war, though none expected it. Britain focused on building its Royal Navy, which was already stronger than the next two navies combined. Germany, France, Austria, Italy, Russia, and some smaller countries set up conscription systems. Young men would serve for 1 to 3 years in the army, then spend 20 years or so in the reserves with annual summer training.

Each country created a mobilization system to quickly call up reserves and send them to key points by train. These plans were updated and expanded every year. Each country stockpiled weapons and supplies for armies of millions.

In 1874, Germany had a regular army of 420,000 with 1.3 million reserves. By 1897, the regular army was 545,000 strong, and the reserves were 3.4 million. France had 3.4 million reservists in 1897, Austria 2.6 million, and Russia 4.0 million. All war plans were perfected by 1914, though Russia and Austria were less effective. All plans aimed for a quick, decisive war.

France's Search for Allies

For a few years after its defeat in 1871, France felt a strong desire for revenge against Germany, especially for the loss of Alsace and Lorraine. French leaders were not obsessed with revenge, but strong public opinion meant friendship with Germany was impossible unless the provinces were returned. Germany would not allow this. So, Germany worked to isolate France, and France sought allies against Germany, especially Russia and Britain.

France had colonies in Asia and looked for alliances, finding a possible ally in Japan. At Japan's request, Paris sent military missions to help modernize the Japanese army. Conflicts with China over Indochina reached a peak during the Sino-French War (1884–1885). The treaty ending the war gave France control over northern and central Vietnam.

Bismarck's foreign policies had successfully isolated France. After Bismarck was fired, Kaiser Wilhelm made unpredictable decisions that confused diplomats. Germany ended its secret treaties with Russia and rejected close ties with Britain. France saw its chance, as Russia was looking for a new partner, and French bankers invested heavily in Russia's economy. In 1893, Paris and St. Petersburg signed an alliance. France was no longer isolated, but Germany was increasingly isolated, with only Austria as a serious ally. Britain also started moving toward alliances, leaving its "splendid isolation." By 1903, France settled its disputes with Britain. After Russia and Britain settled their disputes over Persia in 1907, the way was open for the Triple Entente of France, Britain, and Russia. This formed the basis of the Allies in World War I.

Franco-Russian Alliance

France was deeply divided between royalists and republicans. At first, republicans seemed unlikely to ally with Russia. Russia was poor, not industrialized, very religious, and authoritarian, with no democracy. It oppressed Poland and persecuted political liberals. But France was increasingly frustrated by Bismarck's success in isolating it. France had problems with Italy, which was allied with Germany and Austria-Hungary. Paris tried to approach Berlin, but was rejected. After 1900, there was a threat of war between France and Germany over French expansion in Morocco. Britain was still in "splendid isolation." Colonial conflicts in Africa brought Britain and France to a major crisis: the Fashoda crisis of 1898 almost led to war and ended with France's humiliation, making it hostile to Britain.

By 1892, Russia was France's only chance to break its diplomatic isolation. Russia had been allied with Germany, but the new Kaiser Wilhelm removed Bismarck in 1890 and ended the "Reinsurance treaty" with Russia. Russia was now alone and, like France, needed a military alliance to contain Germany's strong army. The Pope, angered by German anti-Catholicism, worked to bring Paris and St. Petersburg together. Russia desperately needed money for railways and ports. The German government refused to let its banks lend money to Russia, but French banks eagerly did so. By 1895, France and Russia had signed the Franco-Russian Alliance, a strong military alliance to join in war if Germany attacked either of them. France had finally escaped its isolation.

To further isolate Germany, France worked hard to win over Great Britain, especially with the Entente Cordiale in 1904. Then, after Russia and Britain settled their disputes in 1907, the Triple Entente of France, Britain, and Russia was formed. This became the basis of the Allies in World War I. By 1914, Russia and France worked together, and Britain was hostile enough toward Germany to join them as soon as Germany invaded Belgium.

British-German Relations Worsen: 1880–1904

In the 1880s, relations between Britain and Germany improved because leaders like Lord Salisbury and Bismarck were practical conservatives who largely agreed on policies. There were several ideas for a formal treaty between Germany and Britain, but nothing came of them. Britain preferred its "splendid isolation." However, relations steadily improved until 1890, when Bismarck was fired by the aggressive new Kaiser Wilhelm II. In January 1896, the Kaiser increased tensions with his "Kruger telegram" congratulating the Boer president for fighting off a British raid. German officials had stopped the Kaiser from proposing a German protectorate over the Transvaal. In the Second Boer War, Germany sympathized with the Boers.

In 1897, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz became German Naval Secretary and began turning the small German Navy into a world-class force that could challenge the British Royal Navy. The British responded with new technology, like the Dreadnaught battleship, and stayed ahead.

The Imperial German Navy was not strong enough to fight the British in World War I. The one big naval battle, the Battle of Jutland, failed to end Britain's control of the seas or break its blockade. Germany turned to submarine warfare. The laws of war required allowing passengers and crew to get into lifeboats before sinking a ship. The Germans ignored this and sank the Lusitania in 1915 in minutes. The U.S. demanded they stop, and Germany did. But in early 1917, Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff successfully argued to restart unrestricted submarine warfare to starve the British. The German high command knew this meant war with the United States but thought American mobilization would be too slow to stop a German victory.

Two Crises in Morocco

Morocco, on Africa's northwest coast, was the last major territory in Africa not controlled by a colonial power. By 1900, Morocco was in chaos with local wars, bankruptcy, and tribal revolts. No one was in charge. The French Foreign Minister saw an opportunity to stabilize the situation and expand the French empire. France decided to use both diplomacy and military force. With British approval, France would control the Sultan, ruling in his name and extending French control. British approval came in the Entente Cordiale of 1904.

Germany didn't want Morocco itself but felt embarrassed that France was gaining while Germany wasn't. On March 31, 1905, Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II visited Tangier, Morocco's capital, and gave a threatening speech demanding an international conference to ensure Morocco's independence, with war as the alternative. Germany's goal in the First Moroccan Crisis was to boost its prestige and weaken the Entente Cordiale between Britain and France. Germany's plan backfired when Britain made it clear that if Germany attacked France, Britain would intervene on France's side. In 1906, the Algeciras Conference ended the crisis with a diplomatic defeat for Germany, as France gained the main role in Morocco. This brought London and Paris much closer and made it likely they would be allies if Germany attacked either one. The German adventure failed, leaving Germany more isolated and alienated. A major result was increased frustration and readiness for war in Germany, spreading beyond leaders to much of the press and most political parties.

In the Agadir Crisis of 1911, France used force to gain more control over Morocco. The German Foreign Minister was not against this but felt Germany deserved some compensation elsewhere in Africa. He sent a small warship, made threats, and stirred up anger among German nationalists. France and Germany soon agreed on a compromise. However, the British government was alarmed by Germany's aggression toward France. David Lloyd George gave a dramatic speech that criticized the German move as an unacceptable humiliation. There was talk of war, and Germany backed down. Relations between Berlin and London remained bad.

The Great War: World War I

World War I was a global conflict from 1914 to 1918. It involved the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary, later joined by the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria) fighting the "Entente" or "Allied" powers. The Allies were led by Britain, Russia, and France from 1914, later joined by Italy in 1915, and other countries like Romania in 1916. The United States, initially neutral, tried to help make peace. But in April 1917, it declared war on Germany. The U.S. worked with the Allies but didn't formally join them, and it negotiated peace separately.

Despite defeating Romania in 1916 and Russia in March 1918, the Central Powers collapsed in November 1918. Germany accepted an "armistice," which was basically a total surrender. Much of the diplomatic effort of the major powers was focused on getting neutral countries to join their side by promising them enemy territory after victory. Britain, the United States, and Germany spent huge amounts of money funding their allies. Propaganda campaigns were a priority for the major powers to keep morale high at home and weaken morale in enemy countries. They also tried to cause trouble by funding political groups that tried to overthrow enemy governments, like the Bolsheviks did in Russia in 1917.

Both sides made secret agreements with neutral countries to get them to join the war. They promised land from enemy territory after winning. Some land was promised to several nations, so some promises had to be broken. This left lasting bitter feelings, especially in Italy. Blaming the war partly on secret treaties, President Wilson called for "open agreements, openly arrived at" in his Fourteen Points.

Paris Peace Conference and Versailles Treaty: 1919

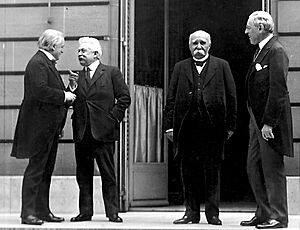

The world war was settled by the winners at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. 27 nations sent representatives, but the defeated countries were not invited.

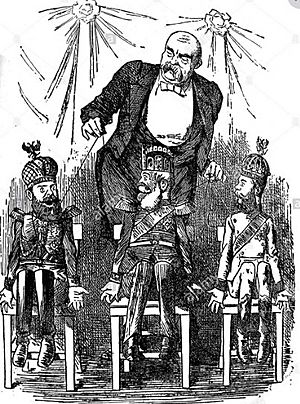

The "Big Four" were President Woodrow Wilson of the United States, Prime Minister David Lloyd George of Great Britain, Georges Clemenceau of France, and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando. They met informally 145 times and made all the major decisions, which others then approved.

The main decisions were:

- Creating the League of Nations.

- Five peace treaties with the defeated enemies (the most important was the Treaty of Versailles with Germany).

- Heavy payments (reparations) forced on Germany.

- Giving Germany's and the Ottoman Empire's overseas lands as "mandates" (controlled by other countries), mainly to Britain and France.

- Drawing new national borders (sometimes with votes) to better reflect nationalism.

In the "guilt clause" (section 231), the war was blamed on "aggression by Germany and her allies." Germany only paid a small part of the reparations before they were stopped in 1931.

See also

- International relations (1648–1814)

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- International relations (1919–1939)

- List of modern great powers

- History of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- History of French foreign relations

- History of German foreign policy

- Foreign policy of the Russian Empire

- History of United States foreign policy

- New Imperialism

- History of colonialism

- Concert of Europe

- Timeline of imperialism

- European balance of power

Images for kids

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |