George F. Kennan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George F. Kennan

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| United States Ambassador to Yugoslavia | |

| In office May 16, 1961 – July 28, 1963 |

|

| President | John F. Kennedy |

| Preceded by | Karl L. Rankin |

| Succeeded by | Charles Burke Elbrick |

| United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union | |

| In office May 14, 1952 – September 19, 1952 |

|

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Alan G. Kirk |

| Succeeded by | Charles E. Bohlen |

| Counselor of the United States Department of State | |

| In office August 4, 1949 – January 1, 1950 |

|

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Charles E. Bohlen |

| Succeeded by | Charles E. Bohlen |

| 1st Director of Policy Planning | |

| In office May 5, 1947 – May 31, 1949 |

|

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Paul H. Nitze |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

George Frost Kennan

February 16, 1904 Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died | March 17, 2005 (aged 101) Princeton, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Annelise Sorensen

(m. 1931) |

| Alma mater | Princeton University (AB) |

| Profession |

|

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He is best known for creating the idea of "containment" during the Cold War. This was a plan to stop the Soviet Union (USSR) from spreading its power. Kennan also gave many talks and wrote books about the relationship between the Soviet Union and the United States. He was part of a group of important foreign policy experts called "The Wise Men."

In the late 1940s, Kennan's ideas helped shape the Truman Doctrine. This was a major U.S. foreign policy to contain the USSR. His "Long Telegram" from Moscow in 1946 and his 1947 article "The Sources of Soviet Conduct" were very important. In these, he argued that the Soviet government naturally wanted to expand. He said its influence needed to be "contained" in areas important to the United States. These writings helped explain why the Truman administration started its new anti-Soviet policy. Kennan also played a big part in creating key Cold War programs, like the Marshall Plan.

After his ideas became U.S. policy, Kennan started to criticize them. By late 1948, he believed the U.S. could talk positively with the Soviet government. However, the Truman administration did not listen to his suggestions. His influence became less important, especially after Dean Acheson became Secretary of State in 1949. Soon after, the U.S. Cold War strategy became more forceful and military-focused. This made Kennan sad, as he felt his original ideas were misunderstood.

In 1950, Kennan left the State Department. He later served briefly as an ambassador in Moscow and longer in Yugoslavia. He then became a critic of U.S. foreign policy, focusing on realism. He continued to study international affairs at the Institute for Advanced Study from 1956 until he died in 2005 at 101 years old.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Diplomatic Career

- Later Life and Views

- Published Works

- Awards and Honors

- See also

Early Life and Education

George Kennan was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. His father, Kossuth Kent Kennan, was a lawyer. His mother, Florence James Kennan, died two months after he was born. Kennan always felt sad about not having a mother. He was not close to his father or stepmother, but he was close to his older sisters.

When he was eight, he went to Germany to live with his stepmother and learn German. He later attended St. John's Military Academy in Wisconsin. In 1921, he started at Princeton University. Kennan was shy and found his college years difficult because he was not used to the rich environment of the Ivy League schools.

Diplomatic Career

First Steps in Diplomacy

After getting his history degree in 1925, Kennan thought about going to law school. But it was too expensive, so he joined the new United States Foreign Service. After studying in Washington, he got his first job as a vice consul in Geneva, Switzerland. A year later, he moved to Hamburg, Germany.

In 1928, Kennan thought about leaving the Foreign Service to go back to school. Instead, he was chosen for a special program to train as a linguist. This allowed him to study for three years without leaving his job.

In 1929, Kennan began studying Russian history, politics, and culture at the University of Berlin. He followed in the footsteps of his grandfather's cousin, George Kennan, who was a 19th-century expert on Imperial Russia. During his career, Kennan learned many languages, including German, French, Polish, and Norwegian.

In 1931, Kennan was sent to the American office in Riga, Latvia. There, he worked on Soviet economic issues. He became very interested in Russian affairs. When the U.S. started formal diplomatic relations with the Soviet government in 1933, Kennan went with Ambassador William C. Bullitt to Moscow. By the mid-1930s, Kennan was one of the trained Russian experts at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. He and other officials believed there was little chance for cooperation with the Soviet Union. Kennan also studied Joseph Stalin's Great Purge, which was a time of great violence and arrests in the Soviet Union. This deeply affected his views on the Soviet government.

Time at the Soviet Embassy

Kennan strongly disagreed with Joseph E. Davies, the next ambassador to the Soviet Union. Davies defended Stalin's Great Purge. Kennan had no influence on Davies's decisions. Davies even suggested Kennan be moved out of Moscow for "his health." Kennan thought about quitting but instead took a job at the State Department in Washington.

Prague and Berlin

In September 1938, Kennan was moved to a job in Prague. After Nazi Germany took over Czechoslovakia at the start of World War II, Kennan was sent to Berlin. He supported the U.S. Lend-Lease policy, which provided aid to Allied nations. However, he warned against supporting the Soviets, as he did not see them as good allies. He was held in Germany for six months after Germany declared war on the United States in December 1941.

Lisbon and the Azores

In September 1942, Kennan was assigned to the American office in Lisbon, Portugal. He managed intelligence and base operations there. In July 1943, the American Ambassador in Lisbon died, and Kennan became the temporary head of the U.S. Embassy.

While in Lisbon, Kennan played a key role in getting Portugal to allow American forces to use the Azores Islands during World War II. He took the initiative to speak directly with President Roosevelt. He got a letter from the President to the Portuguese leader, Salazar, which helped secure the use of the Azores.

Second Soviet Posting

In January 1944, Kennan was sent to London. He worked for the European Advisory Commission, which helped plan Allied policy in Europe. He felt frustrated with the State Department, believing they ignored his skills as a Russia expert. However, within months, he was appointed deputy chief of the mission in Moscow. This happened at the request of W. Averell Harriman, the ambassador to the USSR.

The "Long Telegram"

In Moscow, Kennan again felt his ideas were ignored by President Truman and other leaders in Washington. Kennan tried many times to convince policymakers to stop planning cooperation with the Soviet government. He wanted them to focus on a "sphere of influence" policy in Europe to reduce Soviet power. Kennan believed a union of Western European countries was needed to counter Soviet influence.

Kennan served as deputy head of the mission in Moscow until April 1946. Near the end of his time there, the Treasury Department asked the State Department to explain recent Soviet actions. On February 22, 1946, Kennan responded with a long, 5,363-word message, known as "The Long Telegram." He sent it from Moscow to Secretary of State James Byrnes.

In the telegram, Kennan explained a new strategy for diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. He argued that the Soviet view of the world came from a deep sense of insecurity. After the Russian Revolution, this insecurity mixed with communist ideas. He said Soviet behavior was mainly due to the needs of Joseph Stalin's government. Stalin needed a hostile world to justify his harsh rule. Stalin used Marxism-Leninism to explain the Soviet Union's fear of the outside world and its need for strict control.

Kennan suggested that the solution was to make Western countries stronger. This would make them safe from the Soviet challenge while waiting for the Soviet government to become less aggressive. Kennan's new policy of "containment" meant that Soviet pressure had to be "contained by the smart and careful use of counterforce at many changing geographical and political points."

At the National War College

The "Long Telegram" brought Kennan to the attention of Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal. Forrestal was a strong supporter of a tough policy against the Soviets. He helped bring Kennan back to Washington. There, Kennan became the first deputy for foreign affairs at the National War College. He also strongly influenced Kennan's decision to publish the "X" article.

In March 1947, President Truman asked Congress for money for the Truman Doctrine. This was to fight Communism in Greece. Truman stated, "I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures."

The "X" Article

Unlike the "Long Telegram," Kennan's article, published in July 1947 in Foreign Affairs magazine, used the fake name "X." It was called "The Sources of Soviet Conduct." This article argued that Stalin's policy was shaped by a mix of Marxist–Leninist ideas and Stalin's need to use the idea of "capitalist encirclement" to control Soviet society. Kennan said that Stalin would not change his goal of overthrowing Western governments.

His new policy of containment stated that Soviet pressure had to be "contained by the smart and careful use of counter-force at many changing geographical and political points." Kennan also argued that the United States would have to do this containment alone. If it could do so without harming its own economy and stability, the Soviet system would eventually break apart or become less harsh.

The "X" article caused a big debate during the Cold War. Walter Lippmann, a leading American writer on international affairs, strongly criticized it. He called Kennan's strategy "a strategic monster" that would require supporting many different countries. Lippmann thought diplomacy should be the main way to deal with the Soviets. Soon, it was unofficially revealed that "X" was Kennan. This made the "X" article seem like an official statement of the Truman administration's new policy.

Kennan later said that he did not mean the "X" article to be a strict rule for policy. He kept saying that the article did not mean the U.S. should automatically fight Soviet expansion everywhere. He also meant that political and economic methods, not military ones, should be the main tools of containment. In a 1996 interview, Kennan said his ideas about containment were "distorted by the people who understood it and pursued it exclusively as a military concept." He believed this led to "40 years of unnecessary, fearfully expensive and disoriented process of the Cold War."

Influence Under Secretary Marshall

Between April 1947 and December 1948, when George C. Marshall was Secretary of State, Kennan had more influence than at any other time in his career. Marshall valued his strategic thinking. He asked Kennan to create and lead the Policy Planning Staff, which was the State Department's internal think tank. Kennan became its first director. Marshall relied heavily on him for policy ideas. Kennan played a central role in writing the Marshall Plan.

Kennan believed the Soviet Union was too weak to risk war. However, he thought it could expand into Western Europe through secret actions, especially because Communist parties were popular there after World War II. To stop this, Kennan suggested giving economic aid and secret political help to Japan and Western Europe. This would help revive Western governments and capitalism. In June 1948, Kennan proposed secret help to non-Moscow-aligned left-wing parties and labor unions in Western Europe. This was to create a split between Moscow and working-class movements. In 1947, Kennan supported Truman's decision to give economic aid to the Greek government fighting Communist rebels, but he was against military aid.

Kennan also suggested that the U.S. change its negative view of Francisco Franco's anti-communist government in Spain. This was to gain U.S. influence in the Mediterranean. His idea helped start a new phase of U.S.–Spanish relations, leading to military cooperation after 1950. Kennan also helped plan American economic aid to Greece. He insisted on a capitalist way of development and economic ties with the rest of Europe.

In 1949, Kennan suggested a plan for reuniting Germany, called "Program A" or "Plan A." He argued that dividing Germany could not last forever. He believed Americans would get tired of occupying their part of Germany and want to leave. Or, the Soviets might pull their troops out of East Germany, forcing the U.S. to do the same. Kennan also felt that Germans were too proud to be occupied forever. His solution was to reunite and neutralize Germany. Most British, American, French, and Soviet forces would leave, except for small groups near the border. A four-power group would oversee things, but Germans would mostly govern themselves.

Differences with Secretary Acheson

Kennan's influence quickly dropped when Dean Acheson became Secretary of State in 1949. Acheson did not see the Soviet "threat" as mainly political. He saw events like the Berlin blockade (1948), the first Soviet nuclear weapon test (1949), the Communist revolution in China (1949), and the start of the Korean War (1950) as proof of a military threat. Truman and Acheson decided to define the Western sphere of influence and create alliances. Kennan argued that Asia should not be included in "containment" policies. He felt the U.S. was trying to do too much in Asia. Instead, he thought Japan and the Philippines should be the "cornerstone of a Pacific security system."

Acheson approved Program A for Germany, but it faced strong objections from the Pentagon and within the State Department. Also, the British and French governments did not support it. They were afraid of what might happen if they loosened control over Germany so soon after World War II. In May 1949, a twisted version of Plan A was leaked to the French press. It wrongly suggested the U.S. would leave all of Europe for a united and neutral Germany. Because of the uproar, Acheson canceled Plan A.

Kennan resigned as director of policy planning in December 1949 but stayed as a counselor until June 1950. In January 1950, Acheson replaced Kennan with Paul Nitze, who was more focused on military power. Kennan then accepted a position at the Institute for Advanced Study. In October 1949, the Chinese Communists won the Chinese Civil War. This "Loss of China" caused a strong reaction in the U.S. Many accused the Truman administration of being careless. Kennan found this atmosphere of fear and accusations, known as "McCarthyism," very uncomfortable.

Acheson's policy became the basis of Cold War policy, outlined in NSC 68, a secret report from April 1950. Kennan disagreed with NSC 68. He rejected the idea that Stalin planned to conquer the world. Kennan argued that Stalin actually feared spreading Russian power too thin. He felt NSC 68 would make U.S. policies too strict, simple, and military-focused. Acheson overruled Kennan.

Kennan opposed building the hydrogen bomb and rearming Germany, which were policies supported by NSC 68. During the Korean War (which started in June 1950), Kennan argued against advancing beyond the 38th parallel into North Korea. He thought this would be dangerous.

Memo to Dulles

On August 21, 1950, Kennan wrote a long memo to John Foster Dulles, who was working on the U.S.-Japanese peace treaty. Kennan said U.S. policy in Asia was "little promising" and "fraught with danger." About the Korean War, Kennan wrote that American policies were based on "emotional, moralistic attitudes." He warned these could lead to conflict with the Russians. He supported intervening in Korea but said it was not essential to have an anti-Soviet Korean government control all of Korea. Kennan worried about General Douglas MacArthur's wide power in Asia, feeling MacArthur's judgment was poor.

Criticism of American Diplomacy

Kennan's 1951 book, American Diplomacy, 1900-1950, strongly criticized U.S. foreign policy over the past 50 years. He warned against the U.S. relying on international groups like the United Nations.

Despite his influence, Kennan never felt truly comfortable in government. He saw himself as an outsider and did not like critics. W. Averell Harriman, the U.S. ambassador in Moscow when Kennan was his deputy, said Kennan "understood Russia but not the United States."

Ambassador to the Soviet Union

In December 1951, President Truman nominated Kennan to be the next United States ambassador to the USSR. The Senate strongly approved his appointment.

Kennan felt that the administration's main goal was to create alliances against the Soviets, rather than negotiate with them. In his memoirs, Kennan wrote that the U.S. expected to achieve its goals "without making any concessions." He doubted this was possible unless the U.S. was "really all-powerful."

In Moscow, Kennan found the atmosphere even more controlled than before. Police guards followed him everywhere, making it hard to meet Soviet citizens. Soviet propaganda at the time accused the U.S. of preparing for war. Kennan wondered if the U.S. had contributed to this belief by making its policies too military-focused.

In September 1952, Kennan made a statement that cost him his ambassadorship. At a press conference, he compared his living conditions in Moscow to those when he was held in Berlin during World War II. The Soviets saw this as comparing them to Nazi Germany. They declared Kennan persona non grata (an unwelcome person) and would not let him re-enter the USSR. Kennan later admitted it was a "foolish thing for me to have said."

Kennan and the Eisenhower Administration

Kennan returned to Washington and had disagreements with Dwight D. Eisenhower's Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles. However, he still worked with the new administration. In the summer of 1953, President Eisenhower asked Kennan to lead a secret team called Operation Solarium. This team studied the pros and cons of continuing Truman's containment policy versus trying to "roll back" Soviet influence. The president seemed to agree with the team's ideas.

Eisenhower's containment policy differed from Truman's because Eisenhower worried about the high cost of military spending. He wanted to minimize costs by acting only when the U.S. could afford to.

In 1954, Kennan spoke as a character witness for J. Robert Oppenheimer when the government tried to take away Oppenheimer's security clearance. Even after leaving government, Kennan was often asked for advice by Eisenhower's officials. When the CIA got the transcript of Khrushchev's "Secret Speech" criticizing Stalin in May 1956, Kennan was one of the first to see it.

In 1957, Kennan left the United States to work as a professor at Balliol College at Oxford University. He was popular with students, and hundreds came to hear his lectures on international relations.

In October 1957, Kennan gave the Reith lectures on the BBC, titled Russia, the Atom and the West. He said that if Germany remained divided, the chances for peace were "very slender." He suggested reuniting and neutralizing Germany, with most foreign forces leaving. He also believed Soviet rule in Eastern Europe was "shaky."

Ambassador to Yugoslavia

During John F. Kennedy's 1960 presidential campaign, Kennan wrote to him with suggestions for improving foreign affairs. Kennan urged the administration to "assure a divergence of outlook and policy between the Russians and Chinese." He thought this could be done by improving relations with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, who wanted to distance himself from Communist China. He also suggested creating divisions within the Soviet bloc by encouraging Eastern European countries to be more independent.

Kennedy offered Kennan the choice of being ambassador to Poland or Yugoslavia. Kennan chose Yugoslavia and started his job in May 1961.

Kennan's task was to strengthen Yugoslavia's policy against the Soviets. He also aimed to encourage other Eastern bloc countries to seek more independence. Kennan found his time in Belgrade much better than his earlier experiences in Moscow. He felt the Yugoslav government treated American diplomats politely.

However, Kennan found his job difficult. President Josip Broz Tito and his foreign minister, Koča Popović, suspected Kennedy would adopt an anti-Yugoslav policy. They saw Kennedy's decision to observe Captive Nations Week as a sign that the U.S. would help anti-communist efforts in Yugoslavia. Tito also believed the CIA and the Pentagon truly controlled American foreign policy. Kennan tried to reassure Tito, but his efforts were hurt by diplomatic mistakes like the Bay of Pigs Invasion and the U-2 spy incident.

Relations between Yugoslavia and the U.S. worsened. In September 1961, Tito held a conference of nonaligned nations. His speeches were seen by the U.S. government as pro-Soviet. Kennan argued that Tito's actions were a way to strengthen Khrushchev against hardliners in Moscow. This also gave Tito credit with the Kremlin against Chinese criticism. Kennan believed Yugoslavia's "unusual position in the Cold War" actually helped U.S. goals. He thought Yugoslavia's example would soon inspire other Eastern bloc countries to demand more freedom.

By 1962, Congress passed laws to stop financial aid to Yugoslavia and revoke its most favored nation status. Kennan strongly protested, saying it would only harm relations. He went to Washington in the summer of 1962 to lobby against the laws but could not change Congress's mind. President Kennedy supported Kennan privately but did not publicly commit, as he did not want to risk his slim majority in Congress.

In a speech on October 27, 1962, Kennan strongly supported Kennedy's policies during the Cuban Missile Crisis. He argued that Cuba was in the American sphere of influence, so the Soviets had no right to place missiles there. Kennan resigned as ambassador in late July 1963.

Later Life and Views

After his time as ambassador to Yugoslavia ended in 1963, Kennan spent the rest of his life in academics. He became a major critic of U.S. foreign policy from a realist viewpoint. He joined the faculty of the Institute for Advanced Study in 1956 and stayed there for the rest of his life.

Opposition to the Vietnam War

During the 1960s, Kennan criticized U.S. involvement in Vietnam. He argued that the United States had little important interest in the region.

In February 1966, Kennan spoke before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He said that focusing too much on Vietnam was hurting U.S. leadership around the world. He accused President Lyndon Johnson's administration of turning his policies into a purely military approach.

Kennan testified that if the U.S. were not already fighting in Vietnam, he would see "no reason why we should wish to become so involved." He was not for an immediate pull-out, saying it could harm U.S. interests. But he added that "there is more respect to be won... by a resolute and courageous liquidation of unsound positions." Kennan compared Johnson's policy in Vietnam to "an elephant frightened by a mouse."

Kennan's testimony was aired live on television, which was rare then. His reputation as the "Father of Containment" made his words get a lot of attention. Before his testimony, 63% of Americans approved of Johnson's handling of the war. Afterward, that number dropped to 49%.

Critic of the Counterculture

Even though Kennan opposed the Vietnam War, he did not support the student protests against it. In his 1968 book Democracy and the Student Left, Kennan criticized left-wing university students. He called them violent and intolerant.

In a speech in June 1968, Kennan criticized authorities for being too "tolerant" with student protests and riots by African Americans. Kennan did not approve of the social changes happening in the 1960s.

Establishment of Kennan Institute

Kennan was always a student of Russian affairs. He helped start the Kennan Institute at the academic institution named for Woodrow Wilson. The Institute is named to honor the American George Kennan (explorer) who studied the Russian Empire. Scholars at the Institute study Russia, Ukraine, and the Eurasian region.

Critic of the Arms Race

When he published the first volume of his memoirs in 1967, Kennan explained that containment did not mean a military build-up. He was never happy that his policy was linked to the Arms Race of the Cold War. In his memoirs, Kennan argued that containment did not require a military-focused U.S. foreign policy. He believed the Soviet Union, weakened by war, was not a serious military threat to the U.S. or its allies at the start of the Cold War. Instead, it was an ideological and political rival.

Kennan believed that the USSR, Britain, Germany, Japan, and North America were the key areas of U.S. interest. In the 1970s and 1980s, as détente (a period of reduced tension) ended, especially under President Reagan, Kennan strongly criticized the renewed arms race.

Opposition to NATO Enlargement

Kennan, who inspired American containment policies, later called NATO's expansion a "strategic blunder of potentially epic proportions."

He opposed the Clinton administration's war in Kosovo and the expansion of NATO (which he had also opposed earlier). He feared both policies would worsen relations with Russia.

In a 1998 interview, after the U.S. Senate approved NATO's first expansion, he said "there was no reason for this whatsoever." He worried it would "inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic" feelings in Russia. He said, "The Russians will gradually react quite adversely and it will affect their policies."

Last Years

Kennan remained active and sharp in his final years, though arthritis made him use a wheelchair. In his later years, Kennan concluded that "the general effect of Cold War extremism was to delay rather than hasten the great change that overtook the Soviet Union." At age 98, he warned about the unexpected results of going to war against Iraq. He said attacking Iraq would be a second war that "bears no relation to the first war against terrorism." He called the Bush administration's efforts to link Al-Qaeda with Saddam Hussein "pathetically unsupportive and unreliable."

In February 2004, scholars, diplomats, and Princeton alumni gathered to celebrate Kennan's 100th birthday. Among those present were Secretary of State Colin Powell and Kennan's biographer, John Lewis Gaddis.

Kennan died on March 17, 2005, at his home in Princeton, New Jersey, at age 101. He was survived by his wife, Annelise, whom he married in 1931, and his four children, eight grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren. Annelise died in 2008 at 98.

In an obituary, The New York Times called Kennan "the American diplomat who did more than any other envoy of his generation to shape United States policy during the cold war." Henry Kissinger said Kennan "came as close to authoring the diplomatic doctrine of his era as any diplomat in our history."

Published Works

During his career at the Institute for Advanced Study, Kennan wrote seventeen books and many articles on international relations. He won the Pulitzer Prize for History, the National Book Award for Nonfiction, the Bancroft Prize, and the Francis Parkman Prize for Russia Leaves the War, published in 1956. He won another Pulitzer and a National Book Award in 1968 for Memoirs, 1925–1950. A second volume of his memories, covering up to 1963, was published in 1972. Other works include American Diplomacy 1900–1950 and Around the Cragged Hill (1993).

His historical works included a six-volume account of relations between Russia and the West from 1875 to his own time. He was mainly concerned with:

- The mistake of the First World War as a policy choice. He argued that the costs of modern war were greater than any benefits.

- The ineffectiveness of high-level diplomacy, like the Conference of Versailles. He felt national leaders were too busy to give enough attention to complex diplomatic issues.

- The Allied intervention in Russia in 1918–19. He believed these actions, by making Russians more nationalistic, might have helped the Bolshevik government survive.

Awards and Honors

George Kennan received many awards and honors during his life. As a scholar and writer, he won the Pulitzer Prize twice and the National Book Award twice. He also received the Francis Parkman Prize, the Ambassador Book Award, and the Bancroft Prize.

Other awards include his election to the American Philosophical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1952). He received Princeton's Woodrow Wilson Award (1976) and the Albert Einstein Peace Prize (1981). In 1989, President George H. W. Bush gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the nation. He also received the Distinguished Service Award from the Department of State (1994) and was named a Library of Congress Living Legend (2000).

Kennan also received 29 honorary degrees. A special position, the George F. Kennan Chair in National Security Strategy, was named after him at the National War College. The George F. Kennan Professorship at the Institute for Advanced Study was also named in his honor.

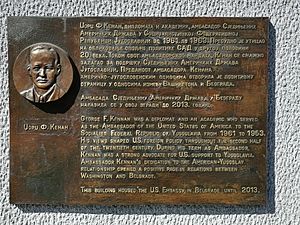

In June 2022, a memorial plaque honoring Kennan was put up in Belgrade, Serbia. It is at the site of the former U.S. embassy where Kennan served from 1961 to 1963.

See also

In Spanish: George F. Kennan para niños

In Spanish: George F. Kennan para niños

- Cold War (1947–1953)

- George F. Kennan: An American Life (2011 biography)

- Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies

- Origins of the Cold War

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |