Woodrow Wilson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Woodrow Wilson

|

|

|---|---|

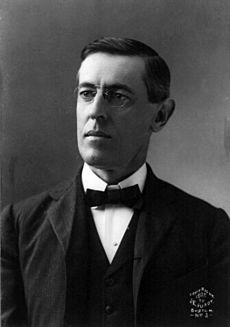

Portrait by Harris & Ewing, 1919

|

|

| 28th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1913 – March 4, 1921 |

|

| Vice President | Thomas R. Marshall |

| Preceded by | William Howard Taft |

| Succeeded by | Warren G. Harding |

| 34th Governor of New Jersey | |

| In office January 17, 1911 – March 1, 1913 |

|

| Preceded by | John Franklin Fort |

| Succeeded by | James Fairman Fielder |

| 13th President of Princeton University | |

| In office October 25, 1902 – October 21, 1910 |

|

| Preceded by | Francis Landey Patton |

| Succeeded by | John Grier Hibben |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Thomas Woodrow Wilson

December 28, 1856 Staunton, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | February 3, 1924 (aged 67) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Washington National Cathedral |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | |

| Children |

|

| Parent |

|

| Education |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Awards | Nobel Peace Prize (1919) |

| Signature |  |

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856 – February 3, 1924) was an American politician and professor. He served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. Wilson was a member of the Democratic Party. Before becoming president, he was the president of Princeton University. He also served as the governor of New Jersey. He won the 1912 presidential election.

As president, Wilson changed the nation's economic rules. He led the United States into World War I in 1917. He was the main person who pushed for the League of Nations. This was an international group created to help keep peace. During his time as president, he also supported some policies that led to racial segregation in federal offices.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was born in Staunton, Virginia. His family had roots in Scotland and Ireland. He was the third of four children. His parents were Joseph Ruggles Wilson and Jessie Janet Woodrow.

Wilson's family moved several times when he was young. He lived in Augusta, Georgia, and Columbia, South Carolina. His father was a Presbyterian pastor. Wilson's earliest memory was hearing about Abraham Lincoln's election. He also heard that a war was coming. His family supported the Southern states during the American Civil War.

Wilson attended Davidson College for a year. Then he transferred to the College of New Jersey. This school is now known as Princeton University. He studied political philosophy and history. He was active in student groups. He was also involved in the school's football and baseball associations.

After graduating from Princeton in 1879, Wilson studied law. He went to the University of Virginia School of Law. He also studied law on his own. He tried to start a law firm in Atlanta in 1882. But he soon decided to focus on political science and history instead.

Marriage and Family Life

In 1883, Wilson met Ellen Louise Axson. She was the daughter of a Presbyterian minister. They got engaged in September 1883. They agreed to wait to marry until Wilson finished graduate school. Ellen was an artist. She agreed to put her art aside to marry Wilson in 1885.

They had three daughters:

- Margaret (born 1886)

- Jessie (born 1887)

- Eleanor (born 1889)

Ellen Wilson's health got worse after Wilson became president. She died in August 1914. Wilson was very sad after her death. In March 1915, he met Edith Bolling Galt. She was a widow and a jeweler. They fell in love and got married on December 18, 1915.

Academic Career

Becoming a Professor

In 1883, Wilson began studying at Johns Hopkins University. He earned a Ph.D. in history and government in 1886. This made him the only U.S. president to have a Ph.D.

From 1885 to 1888, Wilson taught at Bryn Mawr College. This was a new women's college. He taught history and political science. He then moved to Wesleyan University in Connecticut. There, he coached the football team. He also started a debate team.

In 1890, Wilson became a professor at Princeton. He quickly became known as a great speaker. He published several books on history and political science. His book The State was used in many college courses. In this book, he wrote that governments should help people. This included stopping child labor and making factories safe.

Leading Princeton University

In June 1902, Wilson became the president of Princeton University. He worked to make the school better. He tried to make it harder to get into Princeton. He also hired the first Jewish and Roman Catholic professors. However, he also worked to keep African Americans from being admitted to the school.

Wilson's efforts to change Princeton made him famous. But they also affected his health. In 1906, he lost sight in his left eye. This was due to a blood clot and high blood pressure. He eventually became unhappy with the job. He started thinking about running for political office.

Governor of New Jersey

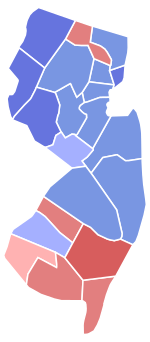

In 1910, Wilson ran for governor of New Jersey. He won the election by a large number of votes. New Jersey was known for corruption at the time. Wilson worked to fight this. He passed laws to make elections fairer. He also signed laws to break up large companies. These laws were called the "Seven Sisters." He also helped set up free dental clinics.

Presidential Election of 1912

In the 1912 election, Wilson ran against two main opponents. These were Republican President William Howard Taft and former President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt ran as a third-party candidate. Eugene V. Debs of the Socialist Party also ran.

Wilson won the election with 42 percent of the popular vote. He received 435 out of 531 electoral votes. His victory made him the first Southerner to become president since the Civil War. He was also the first Democratic president since 1897. And he was the first president to have a Ph.D.

Wilson's Presidency (1913-1921)

First Term: Domestic Policies

Wilson focused on his "New Freedom" plan. This plan aimed to improve life in America. One of his first goals was to lower tariffs. Tariffs are taxes on goods from other countries. He also started the modern income tax.

A major achievement was the Federal Reserve Act. This law created the Federal Reserve System. This system helps manage the nation's money and banks. Wilson also passed laws to promote fair business. The Federal Trade Commission Act and the Clayton Antitrust Act helped stop big companies from having too much power.

World War I

When World War I started in 1914, the U.S. stayed neutral. Wilson tried to help make peace. He won re-election in 1916. He said he had kept the U.S. out of wars. But in April 1917, Germany began sinking American ships. Wilson then asked Congress to declare war on Germany.

Wilson focused on diplomacy during the war. He presented his Fourteen Points plan. This plan was for peace after the war. After the Allied victory in November 1918, Wilson went to Paris. He worked with British and French leaders on the Treaty of Versailles. This treaty officially ended the war.

Wilson strongly supported creating the League of Nations. This was an organization where countries could talk out their problems. He believed it would prevent future wars. The League of Nations was included in the Treaty of Versailles. However, the U.S. Senate did not approve the treaty. So, the United States never joined the League of Nations.

Later Years and Death

Wilson wanted to run for a third term. But he had a severe stroke in October 1919. This made it hard for him to work. His wife and doctor helped him. The Democratic Party chose other candidates for the 1920 election.

On December 10, 1920, Wilson received the Nobel Peace Prize. He won it for his work in creating the League of Nations.

After his second term ended in 1921, Wilson moved to Washington, D.C. He tried to open a law practice. But his health did not get better. He died on February 3, 1924, at age 67. He is buried in the Washington National Cathedral. He is the only president buried in Washington, D.C.

Views on Race

Wilson was born and grew up in the South. His parents supported slavery and the Confederacy. As a scholar, Wilson wrote about the history of the South. He was criticized for supporting racial segregation. At Princeton, he discouraged African Americans from enrolling.

During his presidency, a film called The Birth of a Nation was shown at the White House. This movie supported the Ku Klux Klan. Wilson later spoke out against the film's message.

Memorials and Legacy

Many places are named after Woodrow Wilson. These include:

- The Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library in Virginia.

- His childhood homes in Georgia and South Carolina.

- The Woodrow Wilson House in Washington, D.C.

- The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

- Several schools, including high schools.

- Streets in various cities, like the Rambla Presidente Wilson in Montevideo, Uruguay.

- The USS Woodrow Wilson, a submarine.

- The Woodrow Wilson Bridge near Washington, D.C.

- The Palais Wilson in Geneva, Switzerland.

- A monument in Prague, Czech Republic.

Scholars often rank Wilson as one of the better U.S. presidents. However, he is also criticized for his views on race. His ideas about foreign policy still influence America today.

In Popular Culture

In 1944, a movie called Wilson was released. It was a biopic about his life. The movie starred Alexander Knox. It won five Academy Awards. However, it did not make much money at the box office. No major movie studio has made another film about Wilson since then.

Works

- The History of the American People. In five volumes. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1901–02.

- The Public Papers of Woodrow Wilson. Ray Stannard Baker and William E. Dodd (eds.) In six volumes. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1925–27.

- Study of public administration (Washington: Public Affairs Press, 1955)

- A Crossroads of Freedom: The 1912 Campaign Speeches of Woodrow Wilson. John Wells Davidson (ed.) New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1956.

- The Papers of Woodrow Wilson. Arthur S. Link (ed.) In 69 volumes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967–1994.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Woodrow Wilson para niños

In Spanish: Woodrow Wilson para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |