League of Nations facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

League of Nations

Société des Nations

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920–1946 | |||||||||

|

Semi-official flag (1939)

Semi-official emblem (1939)

|

|||||||||

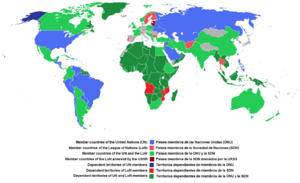

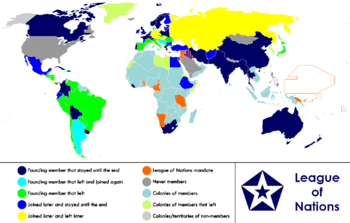

Anachronous world map showing member states of the League during its 26-year history

|

|||||||||

| Headquarters | Geneva | ||||||||

| Official languages | French, English, Spanish | ||||||||

| Type | Intergovernmental organisation | ||||||||

| Secretary-General | |||||||||

|

• 1920–1933

|

Sir Eric Drummond | ||||||||

|

• 1933–1940

|

Joseph Avenol | ||||||||

|

• 1940–1946

|

Seán Lester | ||||||||

| Deputy Secretary-General | |||||||||

|

• 1919–1923

|

Jean Monnet | ||||||||

|

• 1923–1933

|

Joseph Avenol | ||||||||

|

• 1933–1936

|

Pablo de Azcárate | ||||||||

|

• 1937–1940

|

Seán Lester | ||||||||

|

• 1940–1946

|

Francis Paul Walters | ||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||

|

• Treaty of Versailles becomes effective

|

10 January 1920 | ||||||||

|

• First meeting

|

16 January 1920 | ||||||||

|

• Dissolved

|

18 April 1946 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

The League of Nations (LN) was the first worldwide organization where countries came together to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920, following the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. The League's main mission was to prevent wars by encouraging countries to talk about their problems instead of fighting.

The organization was based in Geneva, Switzerland. It stopped its operations in 1946, and many of its responsibilities were taken over by the new United Nations (UN), which was created after the Second World War.

Contents

Origins of the League

Background and Ideas

The idea of a community of nations working together for peace had been discussed for a long time. In 1795, the philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote about a "league of nations" to control conflict. During the 19th century, European countries held meetings called the Concert of Europe to try to avoid war.

By the early 20th century, nations began to create international laws. The Geneva Conventions established rules for war, such as helping wounded soldiers. In 1919, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to create the League. He believed that if countries had a place to discuss their disputes, they could avoid future wars.

Establishing the League

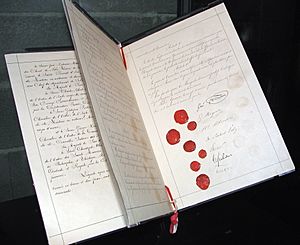

The League was officially created by the Treaty of Versailles, the peace treaty that ended World War I. The rules for the League, known as the Covenant, were written directly into this treaty.

Although President Wilson was a key figure in creating the League, the United States never joined. The U.S. Senate voted against joining because they did not want America to be forced into European conflicts. This absence made the League weaker because one of the world's most powerful countries was not a member.

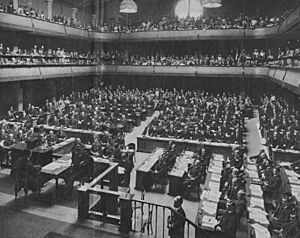

The League held its first meeting in January 1920. Later that year, it moved its headquarters to Geneva, Switzerland. Geneva was chosen because Switzerland was a neutral country that did not take sides in wars.

Organization and Structure

The League of Nations was organized into three main parts:

- The Assembly: This included representatives from all member countries. Each country had one vote. They met once a year to discuss important issues and the budget.

- The Council: This was a smaller group that met more frequently. It had permanent members—Britain, France, Italy, and Japan—and temporary members elected by the Assembly. The Council dealt with political disputes.

- The Secretariat: This was the civil service of the League, based in Geneva. It was led by a Secretary-General and included experts who prepared reports and organized meetings.

Other Agencies

The League also had special agencies to handle specific global issues:

- Permanent Court of International Justice: A court where judges settled legal disputes between countries.

- International Labour Organization (ILO): An agency that worked to improve working conditions, such as limiting working hours and stopping child labour.

- Health Organisation: A group that fought against diseases like malaria and leprosy.

Solving Global Problems

The League worked to solve many problems beyond just stopping wars. It tried to make life better for people around the world.

Helping Refugees

After World War I, there were millions of refugees and prisoners of war who could not go home. The League created a Commission for Refugees, led by Fridtjof Nansen. They helped over 400,000 prisoners return to their families. They also created the Nansen passport, a special travel document for people who had no country to call their own.

Improving Health and Society

The League's Health Organisation worked to prevent epidemics. They taught people about hygiene and helped countries fight diseases. The League also worked to stop slavery and the trade of harmful substances. They tried to protect women and children from unfair treatment.

Settling Border Disputes

The League successfully solved several arguments between countries over land:

- Åland Islands: Both Finland and Sweden claimed these islands. The League decided they should belong to Finland, but the Swedish-speaking population would have their rights protected. Both countries accepted this.

- Upper Silesia: This industrial region was claimed by both Germany and Poland. The League organized a vote and divided the land between the two countries based on the results.

- Mosul: Turkey and Iraq argued over the province of Mosul. The League decided it should be part of Iraq, and the dispute was settled peacefully.

Why the League Failed

Despite its good work in social areas, the League failed in its main goal: to prevent another world war.

Weaknesses

The League had several weaknesses. It did not have its own army to enforce its decisions. It relied on member countries to provide soldiers, which they were often unwilling to do. Also, major powers like the United States never joined. Germany and the Soviet Union were members for only a short time. Japan and Italy left the League when they were criticized for their actions.

Major Failures

In the 1930s, powerful countries began to attack their neighbors, and the League could not stop them:

- Manchuria (1931): Japan invaded Manchuria in China. The League condemned the invasion, but Japan simply quit the League and kept the territory.

- Abyssinia (1935): Italy invaded Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). The League imposed sanctions (penalties) on Italy, but they were weak and did not stop the invasion.

- Spanish Civil War: The League could not stop foreign countries from interfering in the war in Spain.

The End of the League

When World War II began in 1939, the League had effectively failed. It stopped functioning during the war. In 1946, the League was officially dissolved. Its assets and many of its agencies were transferred to the new United Nations.

Legacy of the League

Although the League of Nations could not prevent World War II, it was an important step in history. It was the first time countries tried to create a permanent organization to keep peace. The United Nations learned from the League's mistakes. The UN has a stronger structure and includes all the world's major powers.

The League also left a legacy of international cooperation in health, labor, and refugee aid. The archives of the League are preserved in Geneva and are a valuable resource for historians.

See also

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Sociedad de las Naciones para niños

In Spanish: Sociedad de las Naciones para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |