Fridtjof Nansen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

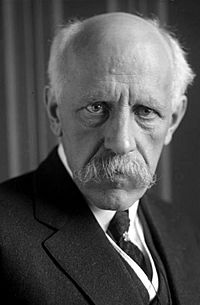

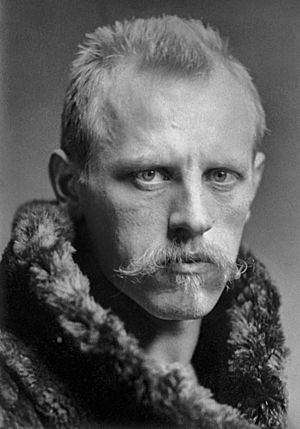

Fridtjof Nansen

|

|

|---|---|

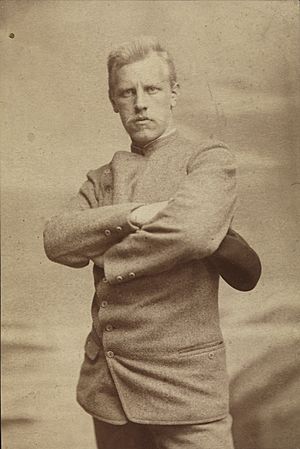

Nansen in 1890

|

|

| Born | 10 October 1861 Store Frøen, Christiania, Norway

|

| Died | 13 May 1930 (aged 68) Polhøgda, Lysaker, Norway

|

| Nationality | Norwegian |

| Education | Royal Frederick University |

| Occupation | Scientist, explorer, diplomat, humanitarian |

| Known for | Dead water Oceanography Polar meteorology Nansen bottle Nansen Ice Sheet Nansen's Fram expedition |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 5, including Odd Nansen |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

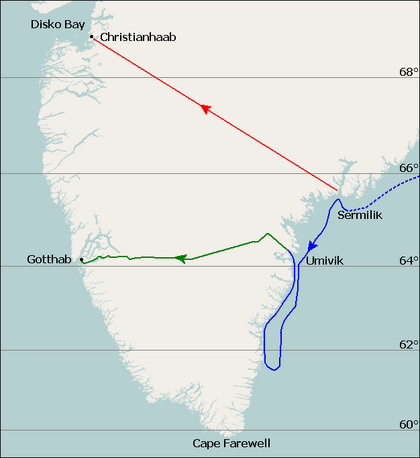

Fridtjof Nansen (born October 10, 1861 – died May 13, 1930) was a famous Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, and humanitarian. He was known for many things during his life. He led the first team to cross the inside of Greenland in 1888, using cross-country skis.

Nansen became internationally famous after reaching a record far north point of 86°14′ during his Fram expedition from 1893 to 1896. Even though he stopped exploring after this, his ways of traveling in polar regions and his new ideas for equipment and clothes helped many future Arctic and Antarctic explorers.

He studied zoology (the study of animals) at the Royal Frederick University in Christiania (now Oslo). Later, he worked at the University Museum of Bergen. His research on the nervous system of small sea creatures helped explain how nerve cells work. After 1896, he became very interested in oceanography (the study of oceans). He went on many science trips in the North Atlantic and helped create modern ocean equipment.

As a respected citizen, Nansen helped Norway become independent from Sweden in 1905. He also helped convince Prince Carl of Denmark to become the new king of Norway. From 1906 to 1908, he worked as Norway's representative in London. There, he helped create a treaty that made sure Norway would stay independent.

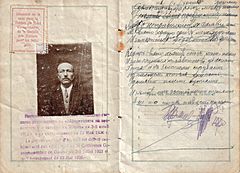

In the last ten years of his life, Nansen worked mainly for the League of Nations, an organization created to promote world peace. He was appointed as their High Commissioner for Refugees in 1921. In 1922, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for helping people who had lost their homes because of World War I and other conflicts. He created the "Nansen passport" for people who had no country, which was accepted by over 50 countries. After he died in 1930, the League created the Nansen International Office for Refugees to continue his important work. This office also won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1938. Many places, especially in the polar regions, are named after him.

Contents

Early Life and Family

The Nansen family came from Denmark. An early explorer of the Arctic Ocean, Hans Nansen (1598–1667), was a trader. Later, his family moved to Norway. Fridtjof Nansen's father, Baldur Fridtjof Nansen, was a lawyer.

Baldur married Adelaide Johanne Thekla Isidore Bølling Wedel-Jarlsberg. They lived at Store Frøen, an estate near Christiania (now Oslo). Fridtjof was born there on October 10, 1861.

Fridtjof's childhood was shaped by the countryside around Store Frøen. In summer, he loved swimming and fishing. In autumn, he hunted in the forests. Winter was all about skiing, which he started at age two.

When he was 10, he tried a ski jump at Huseby. He fell headfirst into the snow. He wrote that people thought he had broken his neck. But his love for skiing never stopped. He saw how skiers from Telemark had a new style, and he wanted to learn it.

At school, Nansen did well but wasn't a top student. Sports and trips into the forests were more important to him. He would live "like Robinson Crusoe" for weeks. These experiences made him very self-reliant. He became a great skier and skater.

In 1877, his mother, Adelaide, died suddenly. His father sold their home and moved to Christiania with his two sons. Nansen kept getting better at sports. At 18, he broke the world record for skating one mile. The next year, he won the national cross-country skiing championship. He would win this championship 11 more times!

Student Life and First Adventures

In 1880, Nansen passed his university entrance exam. He decided to study zoology, saying he chose it because he thought it would let him spend time outdoors. He started his studies at the Royal Frederick University in Christiania in early 1881.

In 1882, Nansen took a big step away from a quiet science life. His zoology professor suggested he go on a sea trip. He would study Arctic animals up close. Nansen was very excited and joined Captain Axel Krefting's sealing ship, Viking.

The trip started on March 11, 1882, and lasted five months. Before sealing began, Nansen focused on science. He found that sea ice forms on the water's surface, not below it. He also showed that the Gulf Stream flows under a cold layer of surface water.

Viking sailed between Greenland and Spitsbergen, looking for seals. Nansen became a skilled shooter. One day, his team shot 200 seals. In July, Viking got stuck in ice near an unexplored part of Greenland. Nansen wanted to go ashore, but he couldn't. This gave him the idea that the Greenland icecap could be crossed. In August, the ship returned to Norway.

Nansen did not go back to formal university studies. Instead, he became a curator in the zoology department at the Bergen Museum. He spent six years there, studying with important scientists. He focused on the nervous system of small sea creatures. His research helped prove that nerve cells (neurons) are separate units. His paper in 1887 became his doctoral thesis.

Crossing Greenland

Planning the Expedition

The idea of crossing the Greenland icecap grew in Nansen's mind while he was in Bergen. In 1887, after finishing his doctoral paper, he started planning. Before him, two explorers, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (1883) and Robert Peary (1886), had gone about 160 kilometers (100 miles) into Greenland from the west coast.

Nansen had a different idea. He wanted to travel from east to west. He reasoned that starting from the east would mean a one-way trip to a populated area on the west coast. There would be no turning back, which fit Nansen's adventurous spirit.

Nansen wanted a small team of six people, not a large expedition. They would pull their supplies on special lightweight sledges. Much of their gear, like sleeping bags and stoves, had to be designed from scratch. Many people thought his plan was too risky. The Norwegian parliament refused to give him money.

However, a Danish businessman, Augustin Gamél, donated money. Other small donations came from Nansen's countrymen. Nansen wanted expert skiers for his team. He chose two Sami people, Samuel Balto and Ole Nielsen Ravna, who were known for traveling on snow. The other team members were Otto Sverdrup, Oluf Christian Dietrichson, and Kristian Kristiansen. All of them had experience in tough outdoor conditions.

The Journey Across Greenland

Nansen's team boarded the sealing ship Jason on June 3, 1888. A week later, they saw the Greenland coast. But thick ice made it hard to get close. With the coast still 20 kilometers (12 miles) away, Nansen decided to launch their small boats. They saw Sermilik Fjord on July 17, which Nansen thought would lead them to the icecap.

They left Jason feeling hopeful. But days of frustration followed as they drifted south. Bad weather and sea conditions stopped them from reaching shore. They spent most of their time camping on the ice, as it was too dangerous to use the boats.

By July 29, they were 380 kilometers (236 miles) south of where they left the ship. That day, they finally reached land. But they were too far south to start their crossing. Nansen ordered them back into the boats to row north. For 12 days, they fought their way north along the coast through ice. They met some native Eskimo people along the way.

On August 11, they reached Umivik Bay, having traveled 200 kilometers (124 miles). Nansen decided they had to start the crossing there. It was getting late in the season. After landing, they spent four days getting ready. They set out on the evening of August 15, heading northwest towards Christianhaab, 600 kilometers (370 miles) away.

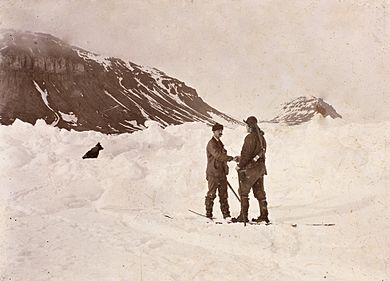

For the next few days, the team struggled to climb the ice. The icecap surface was dangerous, with many hidden cracks. The weather was also bad. They stopped for three days because of strong storms and constant rain. Nansen realized on August 26 that they would not reach Christianhaab in time for the last ship. He changed course to go west, towards Godthaab, which was at least 150 kilometers (93 miles) shorter. The team was happy with the new plan.

They kept climbing until September 11, reaching a height of 2,719 meters (8,921 feet) above sea level. Temperatures on the icecap summit dropped to -45°C (-49°F) at night. After that, the downhill slope made travel easier. But the land was still rough, and the weather was harsh. Progress was slow. New snowfalls made pulling the sledges feel like pulling them through sand.

On September 26, they fought their way down the edge of a fjord towards Godthaab. Sverdrup built a makeshift boat from parts of the sledges, willow branches, and their tent. Three days later, Nansen and Sverdrup started the last part of their journey, rowing down the fjord.

On October 3, they reached Godthaab. The Danish town representative greeted them. He told Nansen that he had earned his doctorate, which Nansen said was the furthest thing from his mind. The team completed their crossing in 49 days. During the journey, they kept records of weather, geography, and other details about the unexplored interior.

The rest of the team arrived in Godthaab on October 12. Nansen soon learned that no ship would call at Godthaab until the next spring. But they could send letters to Norway by a boat leaving Ivigtut at the end of October. He and his team spent the next seven months in Greenland. On April 15, 1889, the Danish ship Hvidbjørnen finally arrived. Nansen wrote that they were sad to leave this place and its people, with whom they had enjoyed themselves so much.

Fame and Marriage

The ship Hvidbjørnen reached Copenhagen on May 21, 1889. News of their crossing had already spread. Nansen and his friends were celebrated as heroes. This welcome was even bigger in Christiania a week later. Thirty to forty thousand people, a third of the city's population, filled the streets to welcome them. This excitement led to the creation of the Norwegian Geographical Society that year.

Nansen became a curator at the Royal Frederick University's zoology collection. This job paid him but had no duties. The university was happy just to be linked with the famous explorer. Nansen spent the next weeks writing his story of the expedition. In June, he visited London and met the Prince of Wales (who later became King Edward VII). He also spoke at the Royal Geographical Society (RGS).

The RGS president said Nansen was the "foremost" northern traveler. He later gave Nansen the Society's important Patron's Medal. Nansen received many honors from groups across Europe. He was asked to lead an expedition to Antarctica but said no. He believed Norway would benefit more from a North Pole conquest.

On August 11, 1889, Nansen announced his engagement to Eva Sars. She was the daughter of a zoology professor. They had met years before at a skiing resort. Eva was three years older than Nansen and a skilled skier. She was also a famous classical singer. Many people were surprised by the engagement, as Nansen had spoken against marriage before. The wedding took place on September 6, 1889.

The Fram Expedition

Planning the North Pole Journey

Nansen first thought about reaching the North Pole in 1884. He read a theory by meteorologist Henrik Mohn about how ocean currents drift across the pole. Items from the Jeannette expedition, which sank off Siberia, were found on the coast of Greenland. Mohn believed this showed a current flowing from east to west across the Arctic Ocean, possibly over the pole.

This idea stayed with Nansen. After his successful Greenland trip, he made a detailed plan for a polar journey. He shared his idea in February 1890. He argued that past expeditions failed because they went against the current. The secret, he said, was to work with it.

His plan needed a very strong and small ship. It had to carry enough fuel and food for twelve men for five years. This ship would enter the ice near where Jeannette sank. It would then drift west with the current towards the pole and beyond. Eventually, it would come out of the ice between Greenland and Spitsbergen.

Experienced polar explorers did not like his idea. Adolphus Greely called it "an illogical scheme of self-destruction." But Nansen still got money from the Norwegian parliament after a strong speech. More money came from private donations across the country.

Building the Fram

Nansen chose naval engineer Colin Archer to design and build the ship. Archer designed an incredibly strong vessel. It had many strong wooden beams and braces. Its rounded hull was made to push the ship upwards when the ice squeezed it. Speed was not as important as making it a safe and warm shelter during their long time stuck in the ice.

The ship was 39 meters (128 feet) long and 11 meters (36 feet) wide. This made it look short and wide. Archer explained that a ship built only for Nansen's goal had to be different from any other. It was named Fram (meaning "Forward") and launched on October 6, 1892.

Nansen picked a team of twelve from thousands of people who wanted to join. Otto Sverdrup, who was with Nansen on the Greenland trip, became the second-in-command. The competition was so tough that Hjalmar Johansen, an army officer and dog-driving expert, joined as a ship's stoker, the only job left.

Into the Ice

Fram left Christiania on June 24, 1893. Thousands of people cheered them on. After a slow trip around the coast, their last stop was Vardø, in northern Norway. Fram left Vardø on July 21. They followed the North-East Passage route along the northern coast of Siberia. Fog and ice made progress slow in the mostly unknown seas.

The crew also experienced "dead water". This is when a ship's movement is slowed by a layer of fresh water on top of heavier salt water. Still, they passed Cape Chelyuskin, the northernmost point of Asia, on September 10.

Heavy ice was seen ten days later, around 78°N latitude. This was near where the Jeannette had sunk. Nansen followed the ice north to a position of 78°49′N, 132°53′E. Then, he ordered the engines stopped and the rudder lifted. From this point, Fram began its drift. The first weeks in the ice were frustrating. The drift was unpredictable, sometimes going north, sometimes south.

By November 19, Fram was south of where it had entered the ice. Only after January 1894 did the ship generally start drifting north. They finally passed the 80°N mark on March 22. Nansen calculated that at this speed, it might take five years to reach the pole. Since the ship's northern progress was very slow, Nansen started thinking about a new plan: a dog sledge journey to the pole. He began practicing dog-driving, making many trips over the ice.

In November, Nansen announced his plan. When the ship passed 83°N latitude, he and Hjalmar Johansen would leave the ship with dogs. They would go for the pole. Fram, under Sverdrup, would continue its drift until it came out of the ice in the North Atlantic. After reaching the pole, Nansen and Johansen would head for the closest known land, Franz Josef Land. Then they would cross to Spitzbergen to find a ship home.

The crew spent the winter of 1894 preparing clothes and equipment for the sledge journey. They built kayaks to carry on the sledges for crossing open water. In January, strong tremors shook the ship. The crew got off, fearing the ship would be crushed. But Fram proved strong enough. On January 8, 1895, the ship's position was 83°34′N. This was beyond the previous record of 83°24′N.

Dash for the Pole

With the ship at 84°4′N, Nansen and Johansen started their journey on March 14, 1895. They had two false starts before this. Nansen planned to cover the 356 nautical miles (659 km) to the pole in 50 days. This meant traveling about 7 nautical miles (13 km) per day. After a week, they were ahead of schedule. However, uneven ice made skiing harder, and their speed slowed. They also realized they were going against a southerly drift. This meant the distance they traveled didn't always equal the distance they progressed north.

On April 3, Nansen began to doubt if they could reach the pole. If their speed didn't improve, their food wouldn't last. He wrote in his diary: "I have become more and more convinced we ought to turn before time." Four days later, after setting up camp, he saw that the way ahead was "a veritable chaos of iceblocks." Nansen recorded their latitude as 86°13′6″N. This was almost three degrees beyond the previous record. He decided to turn back south.

Retreat from the Pole

At first, Nansen and Johansen made good progress south. But on April 13, they had a serious problem. In their rush to leave camp, they forgot to wind their clocks. This made it impossible to know their exact longitude and navigate accurately to Franz Josef Land. They reset their watches based on Nansen's guess that they were at 86°E. From then on, they were unsure of their true position.

Towards the end of April, they saw tracks of an Arctic fox. It was the first sign of a living creature other than their dogs since they left Fram. Soon, they saw bear tracks. By the end of May, they saw seals, gulls, and whales.

On May 31, Nansen calculated they were only 50 nautical miles (93 km) from Cape Fligely, the northernmost point of Franz Josef Land. Travel became harder as warmer weather caused the ice to break up. On June 22, the pair decided to rest on a stable ice floe. They needed to repair their equipment and regain strength. They stayed on the floe for a month.

The day after leaving this camp, Nansen wrote: "At last the marvel has come to pass—land, land, and after we had almost given up our belief in it!" They didn't know if this distant land was Franz Josef Land or a new discovery. They only had a rough map. They reached the edge of the ice pack on August 6. They tied their two kayaks together, raised a sail, and headed for the land.

It soon became clear this land was part of a group of islands. As they moved south, Nansen thought a headland might be Cape Felder on the western edge of Franz Josef Land. Towards the end of August, the weather got colder, and travel became very difficult. Nansen decided to camp for the winter. In a sheltered cove, using stones and moss, they built a hut. This would be their home for the next eight months. They had plenty of bear, walrus, and seal meat. Their biggest challenge was not hunger, but boredom. After quiet Christmas and New Year celebrations, as the weather slowly improved, they began to get ready to leave. But it was May 19, 1896, before they could start their journey again.

Rescue and Return Home

On June 17, while stopping for repairs after a walrus attacked their kayaks, Nansen thought he heard a dog barking and human voices. He went to check and saw a man approaching. It was the British explorer Frederick George Jackson. Jackson was leading an expedition to Franz Josef Land and was camped nearby. Both men were very surprised to see each other. After a moment, Jackson asked, "You are Nansen, aren't you?" Nansen replied, "Yes, I am Nansen."

Johansen was picked up, and the pair were taken to Jackson's camp. They rested and recovered there for several weeks. Nansen later wrote that he could "still scarcely grasp" their sudden good luck. If the walrus attack hadn't delayed them, they might never have met.

On August 7, Nansen and Johansen boarded Jackson's supply ship Windward. They sailed to Vardø, arriving on the 13th. They were greeted by Hans Mohn, who had first suggested the polar drift theory. He happened to be in town. The world quickly learned of Nansen's safe return by telegram. But there was no news of Fram yet.

Nansen and Johansen took the weekly mail steamer south. They reached Hammerfest on August 18. There, they learned that Fram had been seen! It had emerged from the ice north and west of Spitsbergen, just as Nansen had predicted. It was now on its way to Tromsø. It had not passed over the pole, nor had it gone further north than Nansen's record. Without delay, Nansen and Johansen sailed to Tromsø, where they were reunited with their friends.

The journey home to Christiania was a series of celebrations at every port. On September 9, Fram was escorted into Christiania's harbor. The city saw the biggest crowds it had ever seen. King Oscar welcomed the crew. Nansen stayed at the palace for several days as a special guest. Tributes came from all over the world. The British mountaineer Edward Whymper wrote that Nansen had made "almost as great an advance as has been accomplished by all other voyages in the nineteenth century put together."

A National Hero

Scientist and Polar Expert

Nansen's first job after returning was to write about his journey. He did this very quickly, writing 300,000 words in Norwegian by November 1896. The English version, called Farthest North, was ready in January 1897. The book was a huge success and made Nansen financially secure for life.

For the next 20 years, Nansen focused mostly on science. In 1897, he became a professor of zoology at the Royal Frederick University. This gave him a place to work on editing the scientific results of the Fram expedition. This was a much harder task than writing the adventure story. The results were published in six volumes. A later polar scientist said they were as important to Arctic oceanography as the Challenger expedition's results were to other oceans.

In 1900, Nansen became director of the International Laboratory for North Sea Research in Christiania. He also helped start the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. Through this group, Nansen went on his first trip to Arctic waters since the Fram expedition in the summer of 1900. He sailed to Iceland and Jan Mayen Land on the research ship Michael Sars. Soon after he returned, he learned that his Farthest North record had been broken. Members of the Duke of the Abruzzi's Italian expedition reached 86°34′N on April 24, 1900. Nansen took the news calmly, saying: "What is the value of having goals for their own sake? They all vanish... it is merely a question of time."

Nansen was now seen as an expert by all who wanted to explore the North and South Poles. Many explorers, like the Duke of Abruzzi and Adrien de Gerlache, asked him for advice. Although Nansen refused to meet his countryman Carsten Borchgrevink (whom he thought was a fraud), he gave advice to Robert Falcon Scott on polar equipment before Scott's 1901–04 Discovery expedition. At one point, Nansen thought about leading a South Pole expedition himself and asked Colin Archer to design two ships. However, these plans never happened.

By 1901, Nansen's family had grown. A daughter, Liv, was born just before Fram left. A son, Kåre, was born in 1897, followed by a daughter, Irmelin, in 1900, and another son, Odd, in 1901. Their family home, which Nansen built in 1891, was now too small. Nansen bought land in Lysaker and built a large, impressive house. He designed much of it himself.

The house was ready in April 1902. Nansen called it Polhøgda (meaning "polar heights"). It remained his home for the rest of his life. His fifth and final child, a son named Asmund, was born at Polhøgda in 1903.

Diplomat for Norway

The union between Norway and Sweden, which started in 1814, was under great stress in the 1890s. The main issue was Norway's right to have its own consular service. Nansen, though not a politician by nature, spoke out for Norway's rights many times. In the early 1900s, it seemed like the two countries might agree, but talks failed in February 1905. The Norwegian government resigned, and a new one, led by Christian Michelsen, took over. Their goal was to separate from Sweden.

In February and March, Nansen wrote newspaper articles supporting separation. The new prime minister wanted Nansen in his government, but Nansen didn't want to be a politician. However, at Michelsen's request, he went to Berlin and then London. In a letter to The Times, he explained Norway's legal reasons for a separate consular service to English speakers. On May 17, 1905, Norway's Constitution Day, Nansen spoke to a large crowd in Christiania. He said: "Now have all ways of retreat been closed. Now remains only one path, the way forward... to a free Norway." He also wrote a book, Norway and the Union with Sweden, to promote Norway's cause abroad.

On May 23, the Norwegian parliament passed a law creating a separate consular service. King Oscar refused to approve it. On May 27, the Norwegian government resigned, but the king would not accept it. On June 7, the parliament announced that the union with Sweden was dissolved. The Swedish government agreed to let the Norwegian people vote on the dissolution. This vote was held on August 13, 1905. Most people voted for independence. King Oscar then gave up the crown of Norway but remained king of Sweden.

A second vote in November decided that the new independent state should be a monarchy (have a king) instead of a republic. Michelsen's government had already been looking for princes to be king of Norway. King Oscar would not let anyone from his own family take the crown. So, the favorite choice was Prince Charles of Denmark. In July 1905, Michelsen sent Nansen on a secret trip to Copenhagen to convince Charles to accept the Norwegian throne. Nansen succeeded. Soon after the second vote, Charles was made king, taking the name Haakon VII. He and his wife, Princess Maud from Britain, were crowned in Trondheim on June 22, 1906.

In April 1906, Nansen became Norway's first Minister (like an ambassador) in London. His main job was to work with other European countries on a treaty to guarantee Norway's independence. Nansen was well-liked in England and got along well with King Edward. But he found court events and diplomatic duties boring. However, he could still follow his geography and science interests through groups like the Royal Geographical Society. The treaty was signed on November 2, 1907. Nansen felt his job was done. He resigned his post on November 15, even though King Edward wanted him to stay. A few weeks later, while still in England, Nansen learned that Eva was very sick with pneumonia. On December 8, he started for home. But before he reached Polhøgda, he learned by telegram that Eva had died.

Oceanographer and Traveler

After a time of sadness, Nansen went back to London. His government convinced him to stay until King Edward's visit to Norway in April 1908. He officially retired from diplomatic service on May 1, 1908. On the same day, his university professorship changed from zoology to oceanography. This new title showed his recent scientific interests.

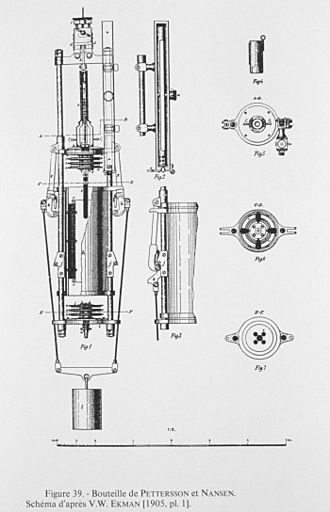

In 1905, he gave data to Swedish physicist Walfrid Ekman. This data helped Ekman explain the Ekman spiral in oceanography. Based on Nansen's observations of ocean currents from the Fram expedition, Ekman found that wind on the sea surface creates currents that spiral downwards.

In 1909, Nansen and Bjørn Helland-Hansen published a paper called The Norwegian Sea: its Physical Oceanography. This was based on the Michael Sars voyage of 1900. Nansen had now retired from polar exploration. He let fellow Norwegian Roald Amundsen use Fram for his North Pole expedition. When Amundsen changed his plan and went for the South Pole, Nansen supported him.

Between 1910 and 1914, Nansen went on several oceanographic trips. In 1910, he did research in the northern Atlantic on the Norwegian naval ship Fridtjof. In 1912, he took his own yacht, Veslemøy, to Bear Island and Spitsbergen. The main goal was to study the saltiness of the North Polar Basin. One of Nansen's lasting contributions to oceanography was designing instruments. The "Nansen bottle" for taking deep water samples is still used today, in an updated version.

At the request of the Royal Geographical Society, Nansen started studying Arctic discoveries. This became a two-volume history of northern exploration up to the 16th century. It was published in 1911 as Nord i Tåkeheimen ("In Northern Mists").

In the summer of 1913, Nansen traveled to the Kara Sea. He was part of a group looking into a possible trade route between Western Europe and Siberia. The group then took a steamer up the Yenisei River to Krasnoyarsk. They traveled on the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok before heading home. Nansen wrote a report from the trip called Through Siberia. He became very interested in and sympathetic to the life and culture of the Russian people. Just before First World War, Nansen joined Helland-Hansen on an oceanographic trip in the eastern Atlantic.

Statesman and Humanitarian

Work with the League of Nations

When World War I started in 1914, Norway stayed neutral. Nansen became president of the Norwegian Union of Defence, but he had few official duties. He continued his scientific work when he could. As the war went on, Norway's trade overseas stopped. This led to severe food shortages. It became very bad in April 1917 when the United States joined the war and put more limits on international trade. Nansen was sent to Washington by the Norwegian government. After months of talks, he got food and other supplies for Norway. In return, Norway had to start a rationing system. When his government was unsure about the deal, he signed it on his own.

A few months after the war ended in November 1918, a plan was accepted to create a League of Nations. This organization would help solve problems between countries peacefully. The League's creation came at a good time for Nansen. It gave him a new way to use his energy. He became president of the Norwegian League of Nations Society. Even though Scandinavian countries were neutral, Nansen's support helped Norway become a full member of the League in 1920. He became one of Norway's three delegates to the League's General Assembly.

In April 1920, the League asked Nansen to help. He started organizing the return of about half a million prisoners of war. These prisoners were stuck in different parts of the world. Three hundred thousand of them were in Russia, which was in the middle of a revolution and civil war. Russia didn't care much about their fate. Nansen reported to the Assembly in November 1920 that about 200,000 men had been sent home. He said, "Never in my life have I been brought into touch with so formidable an amount of suffering."

Nansen continued this work for two more years. In his final report in 1922, he said that 427,886 prisoners had been sent back to about 30 different countries. The committee praised his work, saying his efforts were "heroic" and worthy of his Greenland and Arctic voyages.

The Nansen Mission and Russian Famine

Even before finishing his work with prisoners, Nansen started another humanitarian effort. On September 1, 1921, he became the League's High Commissioner for Refugees. His main job was to help about two million Russian refugees. These people had been displaced by the Russian Revolution.

At the same time, he tried to help with the urgent problem of famine in Russia. A widespread crop failure meant about 30 million people were in danger of starvation. Nansen pleaded for help for the starving. But Russia's new government was feared by other countries. The League was slow to help. Nansen had to rely mostly on money raised from private organizations. His efforts had limited success.

A big problem for Nansen's refugee work was that most refugees had no identity papers. Without legal status, they couldn't go anywhere else. To fix this, Nansen created a document called the "Nansen passport". This was an identity paper for stateless persons. Over time, more than 50 governments accepted it. It allowed refugees to cross borders legally. The passport was first for Russian refugees but was later used for other groups too.

While at a conference in Lausanne in November 1922, Nansen learned he had won the Nobel Peace Prize for 1922. The award recognized his work for:

- Returning prisoners of war.

- Helping Russian refugees.

- Helping millions of Russians suffering from famine.

- His current work for refugees in Asia Minor and Thrace.

Nansen donated the prize money to international relief efforts.

Helping Refugees in Greece and Turkey

After the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, Nansen went to Constantinople. He negotiated the resettlement of hundreds of thousands of refugees. Most were ethnic Greeks who had fled Turkey after the Greek Army's defeat. The poor Greek state could not take them all in. So, Nansen created a plan for a population exchange. Half a million Turks in Greece were returned to Turkey with full financial payment. Loans also helped the Greek refugees settle in their homeland. Despite some debate, the plan worked well over several years.

Armenian Refugees

From 1925 onwards, Nansen spent much time helping Armenian refugees. They were victims of the Armenian genocide during World War I and faced more problems later. His goal was to create a national home for these refugees within Soviet Armenia. His main helper in this was Vidkun Quisling, who later became a Nazi helper in World War II.

After visiting the region, Nansen presented a small plan. It was for irrigating 360 square kilometers (139 square miles) of land where 15,000 refugees could settle. The plan failed because, even with Nansen's strong support, there wasn't enough money. Despite this, Armenians still hold him in high regard.

Nansen wrote Armenia and the Near East (1923), describing the Armenians' struggles after losing independence to the Soviet Union. This book was translated into many languages. After visiting Armenia, Nansen wrote two more books: Across Armenia (1927) and Through the Caucasus to the Volga (1930).

In the League's Assembly, Nansen spoke about many issues besides refugees. He believed the Assembly gave smaller countries like Norway a "unique opportunity for speaking in the councils of the world." He thought the League's success in reducing weapons would be its biggest test. He signed the Slavery Convention on September 25, 1926, which aimed to outlaw forced labor. He supported solving the post-war reparations issue. He also championed Germany joining the League, which happened in September 1926 after Nansen's hard work.

Later Years and Legacy

On January 17, 1919, Nansen married Sigrun Munthe. She was a long-time friend. His children did not like this marriage, and it was not a happy one.

Nansen's work for the League of Nations in the 1920s meant he was often away from Norway. He had little time for scientific work. Still, he published papers now and then. He hoped to travel to the North Pole by airship, but he couldn't get enough money. Roald Amundsen beat him to it, flying over the pole in Umberto Nobile's airship Norge in May 1926. Two years later, Nansen gave a speech remembering Amundsen. Amundsen had disappeared in the Arctic while trying to rescue Nobile, whose airship had crashed. Nansen said Amundsen "found an unknown grave under the clear sky of the icy world."

In 1926, Nansen was elected Rector of the University of St Andrews in Scotland. This was an honorary position, and he was the first foreigner to hold it. In his first speech, he talked about his life and ideas. He also gave a message to the young people of the next generation.

Nansen mostly stayed out of Norwegian politics. But in 1924, former Prime Minister Christian Michelsen convinced him to join a new anti-communist group called the Fatherland League. There were fears that if the Labour Party, which had Marxist ideas, gained power, it would start a revolution. At the League's first meeting in Oslo, Nansen said: "To talk of the right of revolution in a society with full civil liberty, universal suffrage, equal treatment for everyone... [is] nonsense."

Nansen continued to take skiing holidays when he could. In February 1930, at age 68, he went on a short mountain trip with two old friends. They noticed Nansen was slower than usual and tired easily. When he returned to Oslo, he was sick for several months with the flu and then a blood clot. King Haakon VII visited him.

Nansen died of a heart attack on May 13, 1930. He had a non-religious state funeral and was cremated. His ashes were placed under a tree at Polhøgda. His daughter Liv said there were no speeches, just music: Schubert's Death and the Maiden, which Eva used to sing.

Nansen's Lasting Impact

During his life and after, Nansen received many honors from different countries. Lord Robert Cecil, a fellow League of Nations delegate, praised Nansen's wide range of work. He said Nansen worked without caring about his own interests or health. "Every good cause had his support. He was a fearless peacemaker, a friend of justice, an advocate always for the weak and suffering."

Nansen was a pioneer and innovator in many areas. As a young man, he embraced new skiing methods. These changed skiing from just a way to travel in winter to a popular sport. He quickly became one of Norway's best skiers. He later used this knowledge for polar travel, on both his Greenland and Fram expeditions.

He invented the "Nansen sledge" with wide, ski-like runners. He also created the "Nansen cooker" to make spirit stoves more efficient. He developed the layer principle for polar clothing. This replaced heavy, awkward clothes with layers of lightweight material. In science, Nansen is known as one of the founders of modern neurology (the study of the nervous system). He also greatly contributed to early oceanography. He helped set up the Central Oceanographic Laboratory in Christiania.

Through his work for the League of Nations, Nansen helped establish the idea that countries have a shared responsibility for refugees. Right after he died, the League created the Nansen International Office for Refugees. This group continued his work. The Nansen Office faced many challenges, partly because of the large number of refugees from European dictatorships in the 1930s. Still, it got 14 countries to agree to the Refugee Convention of 1933.

It also helped 10,000 Armenians return to Yerevan in Soviet Armenia. It found homes for another 40,000 in Syria and Lebanon. In 1938, the Nansen Office received the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1954, the United Nations, which took over from the League, created the Nansen Medal. It is now called the Nansen Refugee Award. It is given every year to a person, group, or organization for "outstanding work on behalf of the forcibly displaced."

Many places are named after him:

- The Nansen Basin and the Nansen-Gakkel Ridge in the Arctic Ocean.

- Mount Nansen in Canada.

- Mount Nansen, Mount Fridtjof Nansen and Nansen Island, all in Antarctica.

- Nansen Island in the Kara Sea.

- Nansen Land in Greenland.

- Nansen Island in Franz Josef Land.

- 853 Nansenia, an asteroid.

- Nansen crater at the Moon's north pole.

- Nansen crater on Mars.

His mansion, Polhøgda, is now home to the Fridtjof Nansen Institute. This is a group that researches environmental, energy, and resource management.

A 1968 Norwegian/Soviet movie called Just a Life: the Story of Fridtjof Nansen was made about him. Knut Wigert played Nansen.

The Royal Norwegian Navy launched the first of five Fridtjof Nansen-class frigates in 2004. The HNoMS Fridtjof Nansen was the first ship in this series. The cruise ship MS Fridtjof Nansen was launched in 2020.

Awards and Honors

Norway:

Norway:

- Knight of the Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav, May 25, 1889; Grand Cross, September 11, 1896; with Collar, September 7, 1925

- Fram Medal, 1896

- Coronation Medal of King Haakon VII and Queen Maud, 1st Class (Silver), 1906

Sweden: Vega Medal, 1889

Sweden: Vega Medal, 1889 Austria-Hungary: Grand Cross of the Imperial Austrian Order of Franz Joseph, 1898

Austria-Hungary: Grand Cross of the Imperial Austrian Order of Franz Joseph, 1898 Kingdom of Bavaria: Grand Cross of the Merit Order of Saint Michael

Kingdom of Bavaria: Grand Cross of the Merit Order of Saint Michael Denmark:

Denmark:

- Medal of Merit, in Gold and with Crown, 1897

- Knight of the Order of the Dannebrog, May 24, 1889

France:

France:

- Grand Gold Medal of Exploration and Journeys of Discovery, 1897

- Commander of the National Order of the Legion of Honour

Kingdom of Italy:

Kingdom of Italy:

- Grand Officer of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy

Kingdom of Prussia:

Kingdom of Prussia:

- Carl-Ritter Medal (Silver), 1889

- 1878 Alexander von Humboldt Medal (Gold), 1897

Russian Empire:

Russian Empire:

- Constantine Medal, 1907

- Knight of the Imperial Order of Saint Stanislaus, 1st Class

United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

- Patron's Medal, 1891

- Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order, November 13, 1906

United States: Cullum Geographical Medal, 1897

United States: Cullum Geographical Medal, 1897

Writings by Nansen

- Paa ski over Grønland. En skildring af Den norske Grønlands-ekspedition 1888–89. Aschehoug, Kristiania 1890. Translated as The First Crossing of Greenland, 1890.

- Eskimoliv. Aschehoug, Kristiania 1891. Translated as Eskimo Life, (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1893).

- Fram over Polhavet. Den norske polarfærd 1893–1896. Aschehoug, Kristiania 1897. Translated as Farthest North, 1897.

- The Norwegian North Polar Expedition, 1893–1896; Scientific Results (6 volumes, 1901).

- Norge og foreningen med Sverige. Jacob Dybwads Forlag, Kristiania 1905. Translated as Norway and the Union With Sweden, 1905.

- Northern Waters: Captain Roald Amundsen's Oceanographic Observations in the Arctic Seas in 1901. Jacob Dybwads Forlag, Kristiania, 1906.

- Nord i tåkeheimen. Utforskningen av jordens nordlige strøk i tidlige tider. Jacob Dybwads Forlag, Kristiania 1911. Translated as In Northern Mists: Arctic Exploration in Early Times, 1911.

- Gjennem Sibirien. Jacob Dybwads forlag, Kristiania, 1914. Translated as Through Siberia the Land of the Future, 1914.

- Frilufts-liv. Jacob Dybwads Forlag, Kristiania, 1916.

- En ferd til Spitsbergen. Jacob Dybwads Forlag, Kristiania, 1920.

- Rusland og freden. Jacob Dybwads Forlag, Kristiania, 1923.

- Blant sel og bjørn. Min første Ishavs-ferd. Jacob Dybwads Forlag, Kristiania, 1924.

- Gjennem Armenia. Jacob Dybwads Forlag, Oslo, 1927.

- Gjennem Kaukasus til Volga. Jacob Dybwads Forlag, Oslo, 1929. Translated as Through The Caucasus To The Volga, 1931.

- English translations

- Through Siberia, the Land of the Future. London: William Heinemann. 1914.

- Armenia and the Near East. Publisher: J.C. & A.L. Fawcett, Inc., New York, 1928.

See also

In Spanish: Fridtjof Nansen para niños

In Spanish: Fridtjof Nansen para niños

- Arctic exploration

- List of polar explorers

- Nansen Ski Club

- Nansen Ski Jump

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |