Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) facts for kids

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922 was a big conflict between Greece and the Turkish National Movement. It happened after World War I, from May 1919 to October 1922. This war was part of the larger Turkish War of Independence.

The war started because the Allied powers, especially British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, had promised Greece more land from the defeated Ottoman Empire. Greece believed it had a right to these lands because Anatolia was once part of Ancient Greece and the Byzantine Empire.

Greek soldiers landed in Smyrna (now İzmir) on May 15, 1919. They moved deeper into Anatolia, taking control of western and northwestern areas. However, Turkish forces stopped their advance at the Battle of the Sakarya in 1921. The Greek army then lost ground quickly when the Turks launched a major counter-attack in August 1922. The war ended when Turkish forces took back Smyrna.

After the war, the Greek government agreed to the demands of the Turkish National Movement. Greece returned to its old borders, giving Eastern Thrace and Western Anatolia to Turkey. The Allies then created a new agreement called the Treaty of Lausanne, which recognized the independent Republic of Turkey. Greece and Turkey also agreed to exchange populations, meaning many Greeks living in Turkey moved to Greece, and many Turks living in Greece moved to Turkey.

Quick facts for kids Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Turkish War of Independence | |||||||||

Clockwise from top left: Mustafa Kemal at the end of the First Battle of İnönü; Greek soldiers retreat during the last stages; Turkish infantry in trench; Greek infantry charge in river Gediz. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by:

|

Supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

Organization 1922

Equipment 1922

93,000 rifles

2,025 light machine guns 839 heavy machine guns 323 cannons 5,282 swords 198 trucks 33 cars and ambulances 10 aircraft |

Organization 1922

Equipment 1922

130,000 rifles

3,139 light machine guns 1,280 heavy machine guns 418 cannons 1,300 swords 4,036 trucks 1,776 cars and ambulances 50 aircraft |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Regular army:

|

|

||||||||

|

* 20,826 Greek prisoners were taken. Of those about 740 officers and 13,000 soldiers arrived in Greece during the prisoner exchange in 1923. About 7,000 presumably died in Turkish captivity.

|

|||||||||

Contents

- Why the War Started

- Greek Military Actions

- Landing at Smyrna (May 1919)

- Greek Summer Attacks (Summer 1920)

- Treaty of Sèvres (August 1920)

- Greek Advance (October 1920)

- Change in Greek Government (November 1920)

- Battles of İnönü (December 1920 – March 1921)

- New Support for Turkish National Movement

- Battle of Afyonkarahisar-Eskişehir (July 1921)

- Battle of Sakarya (August and September 1921)

- Stalemate (September 1921 – August 1922)

- Turkish Counter-Attack

- Ending the War

- Impact and Consequences

- See also

Why the War Started

This war was connected to the breakup of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. The Ottoman Empire had been on the losing side. The Allies decided to divide its lands.

Promises and Plans

The Allies, especially British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, had promised Greece more land from the Ottoman Empire. This was if Greece joined the war on their side. These lands included parts of western Anatolia around the city of Smyrna. Many Greek people lived there.

Italy was also promised some of these areas. But when Greece occupied Smyrna, Italy was upset. This made it easier for Lloyd George to get France and the United States to support Greece.

Some historians believe that the Greek occupation of Smyrna actually started the Turkish National movement. Others say it was part of Greece's plan to free Greek people in Asia Minor. Before the Great Fire of Smyrna, Smyrna had a larger Greek population than Athens, the capital of Greece.

Greek People in Anatolia

Many Greek-speaking Christian people lived in Anatolia. Greece said they needed protection. Greeks had lived in Asia Minor for a very long time. In 1912, about 2.5 million Greeks lived in the Ottoman Empire.

However, some historians disagree that Greeks were the majority in all the lands Greece claimed. They say Greeks might have been a small majority or a large minority in the Smyrna area. The Ottoman government counted people by religion, not by their ethnic group or language. This makes it harder to know exact numbers.

Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos said Greece was fighting against the old Ottoman government, not against Islam. He wanted to remove the Ottoman government from areas where most people were Greek.

The "Great Idea"

A big reason for the war was Greece's "Megali Idea," or "Great Idea." This was a dream of creating a larger Greece. It would include all areas where Greek people lived, even outside the small Kingdom of Greece.

This idea had been important in Greek politics since Greece became independent in 1830. Greek leaders often spoke about Greece growing bigger. They dreamed of taking back Constantinople (now Istanbul) for Christianity. This city was once the capital of the Christian Byzantine Empire before it fell in 1453.

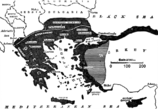

The Great Idea included places like Crete, Macedonia, Thrace, the Aegean Islands, Cyprus, and the coasts of Asia Minor. Asia Minor was a very old part of the Greek world.

Political Problems in Greece

Before World War I, Greece had a big political split called the National Schism. It was between those who supported Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos and those who supported King Constantine. They disagreed on which side Greece should join in the war.

King Constantine wanted Greece to stay neutral. But Venizelos believed Greece should join the Allies. This disagreement caused a deep rift in Greek society. Venizelos even set up a separate government in Northern Greece. With Allied help, he forced the King to leave the country.

This split caused a lot of anger and division in Greece. It also weakened the Greek army during the Asia Minor campaign.

Greek Military Actions

The war's military actions had three main parts. First, Greece landed in Asia Minor and secured the coast (May 1919 to October 1920). Second, Greece went on the attack (October 1920 to August 1921). Third, the Turkish army took the lead (August 1921 to August 1922).

Landing at Smyrna (May 1919)

On May 15, 1919, 20,000 Greek soldiers landed in Smyrna. They took control of the city and nearby areas. British, French, and Greek navies supported them. The Allies said this was allowed by an agreement that let them occupy places if security was threatened.

Many Greek and Armenian people in Smyrna welcomed the Greek troops. The Greek army also included 2,500 Armenian volunteers.

Greek Summer Attacks (Summer 1920)

In the summer of 1920, the Greek army launched successful attacks. They moved towards the Büyük Menderes River valley, Bursa, and Alaşehir. Their goal was to create a stronger defense area around Smyrna. The Greek occupation zone grew to cover most of Western and Northwestern Anatolia.

Treaty of Sèvres (August 1920)

As a reward for Greece's help, the Allies supported giving Eastern Thrace and the Smyrna area to Greece. This treaty officially ended World War I in Asia Minor. It also greatly reduced the size and power of the Ottoman Empire.

On August 10, 1920, the Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Sèvres. It gave Thrace to Greece. Turkey also gave up its rights to the islands of Imbros and Tenedos. The city of Constantinople (Istanbul) and a small strip of European land remained Turkish. The Bosporus Straits were opened to all ships.

Greece was also given control over Smyrna and a large area behind it. However, the Sultan still technically owned Smyrna. The treaty said Smyrna could have its own local government. If, after five years, it wanted to join Greece, the League of Nations would hold a vote. This treaty was never fully approved by either side.

Greek Advance (October 1920)

In October 1920, the Greek army moved even further east into Anatolia. British Prime Minister Lloyd George encouraged this. He wanted to pressure Turkey to sign the Treaty of Sèvres.

This advance started under Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos. But soon after, Venizelos lost power. He was replaced by Dimitrios Gounaris. The goal was to defeat the Turkish Nationalists and force Mustafa Kemal to negotiate peace. The Greeks hoped for a quick battle, but the Turks retreated in an orderly way.

Change in Greek Government (November 1920)

In October 1920, King Alexander died after being bitten by a monkey. This made the upcoming elections very important. The elections were between Venizelos's supporters and the Royalists.

The Royalists promised to end the war in Asia Minor. Venizelos was seen as wanting to continue the war. Most Greeks were tired of fighting. Venizelos lost badly and left the country.

The new government brought back King Constantine. The Allies warned Greece that if the King returned, they would stop all financial and military help. But a vote brought King Constantine back anyway. He then replaced many experienced officers with his own supporters. This caused more problems within the Greek army.

Battles of İnönü (December 1920 – March 1921)

By December 1920, the Greeks had secured their control zone. In early 1921, they tried to advance again. But they met strong resistance from the Turkish Nationalists. The Turks were now better organized and equipped.

The Greek advance was stopped at the First Battle of İnönü on January 11, 1921. This was a small battle, but it was important for the new Turkish government. It led to talks in London where both Turkish governments were present.

The Greek government did not agree to the peace proposals. They believed they could still win. On March 27, the Greeks attacked again in the Second Battle of İnönü. Turkish troops fought fiercely and stopped the Greeks on March 30. The British supported Greek expansion but would not send military help. The Turkish forces received weapons from Soviet Russia.

New Support for Turkish National Movement

By this time, Turkey had settled other conflicts. This freed up more resources to fight the Greek army. France and Italy made their own deals with the Turkish revolutionaries. They saw Greece as being too close to Britain. They even sold military equipment to the Turks.

The new Bolshevik government of Russia also supported the Turkish revolutionaries. They gave Mustafa Kemal's forces money and ammunition. In 1920 alone, they sent 6,000 rifles, over 5 million bullets, and gold. This aid increased in the next two years.

Battle of Afyonkarahisar-Eskişehir (July 1921)

From June 27 to July 20, 1921, the Greek army launched a huge attack. It was against Turkish troops led by İsmet İnönü. The Greeks wanted to cut Anatolia in half by taking important railway towns. They broke through Turkish defenses and captured these towns.

However, the Greek army stopped instead of chasing the Turks. This allowed the Turks to retreat and set up a new defense line east of the Sakarya River. This decision was a turning point for the Greek campaign.

Greek leaders met and decided to continue attacking. They wanted a "final solution" and chose to pursue the Turks towards Ankara. The military leaders were careful and asked for more time and soldiers. But they did not go against the politicians. After a month's delay, which helped the Turks prepare, seven Greek divisions crossed the Sakarya River.

Battle of Sakarya (August and September 1921)

After the Turks retreated, the Greek army advanced to the Sakarya River. This was less than 100 kilometers (60 miles) west of Ankara. The Greeks hoped to trap and destroy the Turkish forces there.

Even with Soviet help, the Turkish army had limited supplies. People had to give their private weapons to the army. Every home had to provide clothing and sandals. The Turkish parliament was not happy with their commander. They wanted Mustafa Kemal and Fevzi Çakmak to take control.

Greek forces marched 200 kilometers (125 miles) through the desert for a week. This meant the Turks could see them coming. The Greeks ran low on food and ammunition.

The Battle of Sakarya lasted 21 days (August 23 – September 13, 1921). The Turks defended their positions fiercely. Both sides were exhausted, but the Greeks were the first to retreat. The sound of cannons could be heard in Ankara.

This was the furthest the Greeks advanced into Anatolia. Within a few weeks, they pulled back to their old lines. Mustafa Kemal and Fevzi Çakmak were given the highest military rank for their service in this battle.

Stalemate (September 1921 – August 1922)

Greece asked the Allies for help, but Britain, France, and Italy decided the Treaty of Sèvres could not be enforced. Italy and France pulled their troops out, leaving Greece alone.

In March 1922, the Allies suggested a ceasefire. Mustafa Kemal refused, as long as Greeks were still in Anatolia. He worked to prepare the Turkish military for a final attack. The Greeks strengthened their defenses but became discouraged by the long, inactive war.

Greece tried to get military support or a loan from Britain. They even thought about threatening British positions in Constantinople. But this plan never happened. Instead, it weakened Greek defenses in Smyrna. Meanwhile, the Turkish forces received more help from Soviet Russia, including weapons and money.

Many people in Greece wanted to withdraw. Some officers who supported Venizelos tried to organize a coup, but it failed.

Historian Malcolm Yapp said that after the failed talks in March, Greece should have pulled back to defensible lines around Izmir. But Greek leaders kept their troops in place and even planned to seize Constantinople, though this plan was later dropped.

Turkish Counter-Attack

Dumlupınar Battle

The Turks launched their big counter-attack, called the "Great Offensive", on August 26. They quickly overran Greek defenses. Afyonkarahisar fell the next day. On August 30, the Greek army was badly defeated at the Battle of Dumlupınar. Many soldiers were captured or killed, and much equipment was lost. This day is now a national holiday in Turkey.

During the battle, Greek generals Nikolaos Trikoupis and Kimon Digenis were captured. On September 1, Mustafa Kemal gave his famous order: "Armies, your first goal is the Mediterranean, Forward!"

Turkish Advance on Smyrna

On September 2, Eskişehir was captured. The Greek government asked Britain to arrange a truce to save Smyrna. But Mustafa Kemal refused. He saw the Greek presence in Smyrna as a foreign occupation. He continued his aggressive military push.

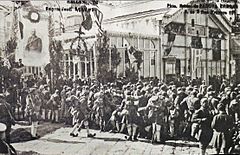

Balıkesir and Bilecik were taken on September 6, and Aydın the next day. Manisa fell on September 8. The government in Athens resigned. Turkish cavalry entered Smyrna on September 9. Gemlik and Mudanya fell on September 11, with an entire Greek division surrendering. The Greek army was completely pushed out of Anatolia by September 18.

-

Entry of the Turkish army commanded by Mustafa Kemal Pasha to Smyrna (Izmir) on September 9, 1922

-

Commander-in-chief Mushir Mustafa Kemal Pasha arrives in Izmir with Mushir Fevzi Pasha and Aide-de-camp Major Salih Bey on September 10, 1922.

Turkish cavalry entered Smyrna on September 9. The Greek headquarters had already left. Mustafa Kemal quickly issued an order, threatening to punish any Turkish soldier who harmed civilians. He wanted to make sure no massacres happened.

However, there were reports of violence against Greek and Armenian people. Their properties were looted. Many eyewitnesses said Turkish soldiers started a fire in the city. The Greek and Armenian parts of the city burned down, while the Turkish and Jewish areas remained.

Chanak Crisis

After taking Smyrna, Turkish forces moved north towards the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits. British, French, and Italian troops were stationed there. Mustafa Kemal said Turkey wanted Asia Minor, Thrace, and Constantinople. He was ready to march on Constantinople if needed.

The British government considered resisting the Turks. They asked their allies and other countries for military help. But only New Zealand offered support. Italian and French forces left their positions, leaving the British alone.

A British general in Constantinople, Charles Harington, prevented his men from firing on the Turks. He warned against any hasty actions. The British finally decided to make the Greeks withdraw from Thrace. This convinced Mustafa Kemal to agree to peace talks.

Ending the War

Armistice and Treaty

The Armistice of Mudanya was signed on October 11, 1922. The Allies kept control of eastern Thrace and the Bosporus. The Greeks had to leave these areas. The agreement started on October 15, 1922.

The armistice was followed by the Treaty of Lausanne. This treaty officially ended the war. As part of this, Turkey and Greece agreed to an exchange of populations.

Population Exchange

About 1.5 million Greek Orthodox Christians living in Turkey were forced to move to Greece. Around 500,000 Turks and Greek Muslims living in Greece were forced to move to Turkey. This agreement meant many people had to leave their homes and move to a new country.

Historians say this exchange completed a process of creating ethnically pure homelands. Many Greeks from Anatolia were not allowed to return to their homes after the treaty was signed.

Reasons for the Outcome

The Greeks thought they could defeat the weakened Turks in just three months. But the Allies, tired from World War I, relied on Greece and did not want to get involved in a new war. They doubted Greece's ability to fight in Anatolia, which was a huge territory.

After the Greeks failed to defeat the Turks in the İnönü battles, Italy started to leave its occupation zone. France also changed its support to the Turks. They wanted a strong buffer state against the Bolsheviks. After the Greeks failed again at the Battle of Sakarya, France signed a treaty with the Turks in October 1921.

The Allies also did not fully let the Greek Navy block the Black Sea coast. This could have stopped Turkish imports of food and supplies.

The Greek army had problems with supplies. While they had enough soldiers, they lacked almost everything else. Greece's economy was poor and could not support a long war. The Greek army also had to control a very large area.

Meanwhile, things improved for the Turks. After World War I, the Allies had taken Ottoman weapons. But the Turkish National Movement needed weapons for its new army. They received support from Soviet Russia, including money and weapons. Italy also helped the Turks by arming and training Turkish troops.

A British military officer who saw the Greek army in June 1921 said it was a very strong fighting force. But the Turkish troops had determined and skilled leaders. They also had the advantage of fighting on their own land.

Mustafa Kemal was able to unite all Turkish people to fight. He presented himself as a revolutionary, a patriot, and a Muslim leader. The Turkish National Movement also received support from Muslims in other countries, who sent money and encouragement.

Impact and Consequences

Suffering and Displacement

During the war, people on both sides suffered greatly. There were reports of violence and destruction. Historians have estimated that many people, including Armenians and Greeks, died during this period.

British historian Arnold J. Toynbee reported seeing many Greek villages burned to the ground. He said Turkish troops deliberately burned each house. There were massacres from 1920 to 1923, especially against Armenians in the East and Greeks in the Black Sea region. By 1922, most Ottoman Greeks in Anatolia had either become refugees or died.

Greeks also suffered in Turkish labor battalions. Many Greek men were forced into these groups. Some reports described these as "white massacres," involving forced marches and starvation.

There were also many reports in Western newspapers about violence against Christian people in Anatolia. The suffering of Pontic Greeks in the Black Sea region is recognized as the Pontian Genocide in Greece and Cyprus.

When the Turkish army entered Smyrna on September 9, 1922, there was widespread disorder. The Christian parts of the city were burned. Tens of thousands of Greeks and Armenians were killed in the fire and related violence.

Greek Actions and "Scorched-Earth" Policy

British historian Arnold J. Toynbee also wrote about violence by Greeks after they landed in Smyrna in May 1919. He and his wife saw violence by Greeks in the Yalova, Gemlik, and Izmit areas. However, British leader Winston Churchill said Greek actions were on a "minor scale" compared to the terrible forced movements of Greeks by the Turks.

During the Battle of Bergama, the Greek army committed violence against Turkish civilians in Menemen. More than 300 Turkish civilians died in İzmit in June 1921.

Some historians claim that during the peace talks, the Turkish negotiator said 1.5 million Anatolian Muslims were either forced to leave or died in Greek-occupied areas. Other historians give much lower estimates for Turkish civilian deaths.

As part of the Lausanne Treaty, Greece agreed to pay for damages caused in Anatolia. However, Turkey agreed to drop these claims because Greece was in a difficult financial situation.

According to many sources, the retreating Greek army used a "scorched-earth policy" as they left Anatolia. This means they destroyed everything in their path. Historian Sydney Nettleton Fisher wrote that the Greek army "committed every known outrage against defenceless Turkish villagers." Norman Naimark noted that the Greek retreat was even more destructive than their occupation.

The Greek army also used this policy during their advance. A Greek lieutenant's diary from July 1921 mentions his unit capturing and burning the town of Pazarcık in a few hours.

A Swedish scholar in Smyrna wrote that the Greek army burned 250 Turkish villages. The Greek scorched-earth policy also included killing a lot of livestock.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra greco-turca (1919-1922) para niños

In Spanish: Guerra greco-turca (1919-1922) para niños

- Outline and timeline of the Greek genocide

- List of massacres during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22)

- Chronology of the Turkish War of Independence

- Occupation of Smyrna

- Population exchange between Greece and Turkey

- Relief Committee for Greeks of Asia Minor

- Asia Minor Defense Organization