Constantine I of Greece facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Constantine I |

|

|---|---|

Constantine I, 1921

|

|

| King of the Hellenes | |

| First reign | 18 March 1913 – 11 June 1917 |

| Predecessor | George I |

| Successor | Alexander |

| Prime ministers |

See list

Eleftherios Venizelos

Dimitrios Gounaris Alexandros Zaimis Stephanos Skouloudis Alexandros Zaimis Nikolaos Kalogeropoulos Spyridon Lambros |

| Second reign | 19 December 1920 – 27 September 1922 |

| Predecessor | Alexander |

| Successor | George II |

| Prime ministers |

See list

|

| Born | 2 August 1868 Athens, Kingdom of Greece |

| Died | 11 January 1923 (aged 54) Palermo, Kingdom of Italy |

| Burial | 14 January 1923 Naples, Italy

22 November 1936Royal Cemetery, Tatoi Palace, Athens, Greece

|

| Spouse |

Sophia of Prussia

(m. 1889) |

| Issue |

|

| House | Glücksburg |

| Father | George I of Greece |

| Mother | Olga Constantinovna of Russia |

| Signature | |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Rank | Field marshal |

| Unit | German Imperial Guard |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

Constantine I (born August 2, 1868 – died January 11, 1923) was the King of Greece for two periods. He reigned from March 18, 1913, to June 11, 1917, and again from December 19, 1920, to September 27, 1922. He was a very important leader during a time of big changes for Greece.

Constantine was the top commander of the Hellenic Army during the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, which Greece lost. But he then led Greek forces to victory in the Balkan Wars (1912–1913). These wars helped Greece grow a lot, adding new lands like Thessaloniki and doubling its size and population. He became king on March 18, 1913, after his father, King George I, was sadly assassinated.

Constantine had a big disagreement with Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos about whether Greece should join World War I. This led to a major split in the country called the National Schism. Constantine made Venizelos resign twice. But in 1917, Constantine himself had to leave Greece. This happened after the Allied countries threatened to attack Athens. His second son, Alexander, then became king.

After King Alexander died, and Venizelos lost an election, people voted for Constantine to return. So, he became king again in 1920. However, he had to give up his throne for the second and last time in 1922. This was after Greece lost the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922. His oldest son, George II, took over as king. King Constantine I died on January 11, 1923, while living away from Greece in Sicily, Italy.

Contents

- Early Life and Education of a Future King

- Olympics and Early Political Challenges

- Military Defeats and Reforms

- Leading Greece in the Balkan Wars

- World War I and the National Schism

- Return to Power and Final Exile

- Later Life and Passing

- Family Life and Children

- Legacy and Cultural Impact

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education of a Future King

Constantine was born in Athens on August 2, 1868. He was the first son of King George I and Queen Olga. His birth was a huge event because he was the first royal family member born in Greece. People were so excited they shouted for him to be named "Constantine." This name was special because it was his grandfather's name and also the name of a legendary "King who would take back Constantinople."

He was officially named Constantine on August 12. His title was Diádochos, which means Crown Prince or "Successor." Important university professors taught him subjects like Greek literature, math, physics, and history. He learned about the Megali Idea, which was a big dream for Greece to expand its borders.

In 1882, he joined the Hellenic Military Academy. After finishing there, he went to Berlin for more military training. He even served in the German Imperial Guard. Constantine also studied political science and business at universities in Heidelberg and Leipzig. By 1890, he became a Major general and took charge of an army group in Athens.

Olympics and Early Political Challenges

In 1895, Constantine got into a political problem. He ordered soldiers to stop a street protest against a new tax. He had told the crowd to complain to the government first. The Prime Minister, Charilaos Trikoupis, asked the King to tell his son not to get involved in politics without talking to the government. King George said Constantine was just following military orders and it wasn't political.

This caused a big debate in Parliament, and Trikoupis ended up resigning. The next Prime Minister, Theodoros Deligiannis, decided to drop the issue.

Constantine also played a key role in bringing the first modern Olympics to Athens. Prime Minister Trikoupis was against hosting the Games. But after Deligiannis won the election, those who wanted the Olympics, including Constantine, got their way. Constantine was very important in organizing the 1896 Summer Olympics. He became the president of the organizing committee. He even asked a rich businessman, George Averoff, to pay for the Panathinaiko Stadium to be rebuilt with white marble.

Military Defeats and Reforms

Constantine was the commander of the army in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. This war ended in a big loss for Greece. After this defeat, many people were unhappy with the monarchy. There were calls to remove the royal princes, especially Constantine, from their army leadership roles.

This unhappiness led to a military uprising in August 1909 called the Goudi coup. After the coup, Constantine and his brothers were removed from the army. However, they were put back in their positions a few months later by the new Prime Minister, Eleftherios Venizelos. Venizelos wanted to gain the trust of King George. He argued that all Greeks, including the King, were proud to see their sons serve in the army. But the royal princes' power in the army was now much more limited.

Leading Greece in the Balkan Wars

In 1912, Greece joined other Balkan countries to form the Balkan League. They were ready for war against the Ottoman Empire. Prince Constantine became the Chief of the Hellenic Army.

The Ottoman Empire made a mistake in planning their defense. They thought Greece would attack in two directions. But Greece, led by Venizelos and the army staff, planned a fast and strong attack towards Thessaloniki. This city had a very important harbor. Only a small Greek force went west to keep Turkish troops busy there.

The main Greek army moved quickly against the Turks in the east. The Greek plan worked very well. The Greeks defeated the Turks twice and reached Thessaloniki in just four weeks. The Greek navy also helped by blocking the Turkish fleet. This meant Turkish reinforcements from Asia could not reach Europe quickly. The capture of Thessaloniki was key because it cut off the railway line between the two main Turkish cities. This made it hard for the Turks to get supplies and control their forces.

Capturing Thessaloniki: A Key Victory

Constantine was the commander-in-chief of the "Army of Thessaly" when the First Balkan War began in October 1912. He led his army to victory at Sarantaporos. At this point, he had his first disagreement with Prime Minister Venizelos. Constantine wanted to go north towards Monastir, where most of the Ottoman army was. He wanted to meet up with Greece's Serb allies there.

However, Venizelos insisted that the army must capture the important port city of Thessaloniki very quickly. He wanted to make sure the Bulgarians didn't get there first. This led to a strong exchange of messages. Venizelos told Constantine that "political reasons of the utmost importance" meant Thessaloniki had to be taken as soon as possible. When Constantine replied that his duty called him to Monastir "unless you forbid me," Venizelos gave a famous three-word order: "I forbid you."

Constantine had no choice but to turn east. After defeating the Ottoman army at Giannitsa, he accepted the surrender of Thessaloniki and its Ottoman soldiers on October 27. This happened less than 24 hours before Bulgarian forces arrived, hoping to capture the city themselves. Capturing Thessaloniki was a huge success. It meant Greece had control of the vital port, which was important for future peace talks.

Victories in Epirus

Meanwhile, the fighting in the Epirus area had stopped. The small Greek force couldn't get past the difficult land and strong Ottoman defenses at Bizani. Once the fighting in Macedonia was over, Constantine moved most of his forces to Epirus and took command. After careful planning, the Greeks broke through the Ottoman defenses in the Battle of Bizani. They captured Ioannina and most of Epirus, including what is now southern Albania.

These victories helped erase the shame of the 1897 defeat. They also made Constantine very popular with the Greek people.

Becoming King and the Second Balkan War

King George I was assassinated in Thessaloniki on March 18, 1913. Constantine then became the new king. At the same time, tensions grew between the Balkan allies. Bulgaria claimed land that Greece and Serbia had taken. In May, Greece and Serbia made a secret agreement to defend each other against Bulgaria. On June 16, the Bulgarian army attacked their former allies, but they were quickly stopped.

King Constantine led the Greek Army in its counterattack during the battles of Kilkis-Lahanas and the Kresna Gorge. The Bulgarian army began to fall apart. They were losing to the Greeks and Serbs, and then the Turks attacked them with fresh troops. Also, Romania advanced south, demanding land. Bulgaria asked for peace and agreed to a ceasefire.

Prime Minister Venizelos suggested that Constantine be given the rank of Field Marshal. His popularity was at its highest. He was seen as the "winner over the Bulgarians," the King who had doubled Greece's territory under his military command.

World War I and the National Schism

The idea that Constantine I was a "German sympathizer" came partly from his marriage to Sophia of Prussia. She was the sister of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany. People also pointed to his studies in Germany and his strong military beliefs.

However, Constantine actually refused Kaiser Wilhelm's request in 1914 for Greece to join the war on Germany's side. He told the Kaiser that while he felt sympathy for Germany, he would not join the war. Constantine also upset the British and French by stopping Prime Minister Venizelos's efforts to bring Greece into the war on the Allied side.

Constantine and his supporters said his choice to stay neutral was because he believed it was the best policy for Greece. They argued it wasn't because of his personal feelings or German family connections, as his opponents claimed.

Admiral Mark Kerr, a British naval officer who knew Constantine, wrote in 1920 that the way the Allied press treated King Constantine was "one of the most tragic affairs."

Even though Venizelos, with Allied help, forced Constantine to leave the throne in 1917, Constantine remained popular with many Greeks. They showed this by voting for his return in a 1920 public vote. Many Greeks saw the Allied actions as an attack on Greece's independence.

Key Events of the National Schism

After the successful Balkan Wars, Greece was very happy. Its land and population had doubled. Under the leadership of Constantine and Venizelos, the future looked bright. However, Constantine had been sick with a lung illness since the Balkan wars and almost died in 1915.

This good situation didn't last. When World War I started, the King and the government disagreed about who should decide Greece's foreign policy during a war.

Constantine had to decide where Greece's support should go. His main concern was Greece's safety. He refused Kaiser Wilhelm's early request for Greece to fight with Germany. He said Greece would stay neutral. Constantine's wife, Queen Sophie, was thought to support her brother, Kaiser Wilhelm. But it seems she was actually pro-British, like her mother. Venizelos strongly supported the Allies. He believed Germany caused the war and that the Allies would win quickly.

Both Venizelos and Constantine knew that Greece, as a country with a lot of sea trade, could not upset the Allies. The Allies had the strongest navies in the Mediterranean. Constantine chose neutrality because he thought it was the best way for Greece to stay safe and keep the new lands it had gained in the Balkan Wars.

In January 1915, the Allies offered Bulgaria and Greece a deal. Bulgaria would get eastern Macedonia from Greece, and Greece would get land in Asia Minor from Turkey after the war. Venizelos agreed, but Constantine said no.

Constantine believed his military judgment was correct, especially after the Allies' failed landing at Gallipoli. Despite Venizelos's popularity and his clear majority in Parliament for supporting the Allies, Constantine opposed him. Venizelos wanted Greece to join the Gallipoli operation, but the King rejected the idea after military leaders advised against it.

In autumn 1915, Bulgaria joined Germany and attacked Serbia. Greece had a treaty with Serbia. Venizelos again urged the King to let Greece join the war. The Hellenic army was called up for defense. But Constantine argued that the treaty only applied to Balkan issues, not a global war. He also said Serbia hadn't sent enough soldiers as required by the treaty.

The British then offered Cyprus to Greece if it joined the war, but Constantine refused this too. Venizelos allowed Allied forces to land in Thessaloniki. This created the Macedonian front to help Serbia, even though the King objected. This action by Venizelos, which went against Greece's neutrality, made the King very angry. He dismissed Venizelos for the second time.

At the same time, Germany offered to protect Greeks living in Turkey if Greece stayed neutral. Constantine's opponents also accused him of secret talks with Germany.

In March 1916, Constantine announced that Greece officially owned Northern Epirus. Greeks had controlled this area since 1914. But Italian and French forces drove the Greek troops out the next year.

In June 1916, Constantine and his prime minister allowed German and Bulgarian forces to occupy Fort Rupel and parts of eastern Macedonia without a fight. This was meant to balance the Allied forces in Thessaloniki. This made many people angry, especially in Greek Macedonia, who now faced a Bulgarian threat. Allied army leaders in Thessaloniki also worried that Constantine's army might attack them from behind.

In July 1916, a fire started in the forest around the royal summer palace at Tatoi. The king and his family were injured but managed to escape. Sixteen people died. Some rumors linked the fire to French agents, but this was never proven. After this, supporters of the King hunted down Venizelos's supporters in Athens.

In August 1916, a military uprising happened in Thessaloniki by officers who supported Venizelos. Venizelos set up a new government there, called the Movement of National Defence. This government created its own army and declared war on Germany and its allies. With Allied support, Venizelos's government took control of half the country, mostly the new lands won in the Balkan Wars. This created the National Schism, a deep division in Greek society between those who supported Venizelos and those who supported the King. This split affected Greek politics for many years, even after World War II. Venizelos publicly asked the King to fire his "bad advisors" and join the war as King of all Greeks, not as a politician. Constantine's government in Athens continued to talk with the Allies about possibly joining the war.

In late 1916, British and French troops landed in Athens. They demanded that Greece hand over military supplies equal to what was lost at Fort Rupel. This was to guarantee Greece's neutrality. After days of tension, they met resistance from pro-royalist forces. After a fight, the Allies left Athens and officially recognized Venizelos's government in Thessaloniki. Constantine became very unpopular with the Allies.

In early 1917, Venizelos's government took control of Thessaly. After the monarchy in Russia fell, Constantine lost his last supporter among the Allies who had been against removing him from the throne. Facing pressure from Venizelos and the British and French, King Constantine finally left Greece for Switzerland on June 11, 1917. His second son, Alexander, became king. The Allied Powers didn't want Constantine's oldest son, George, to be king. They thought George was too pro-German, like his father.

Return to Power and Final Exile

King Alexander died on October 25, 1920, after a strange accident. He was bitten by a monkey while walking his dogs. What seemed like a small injury turned into a serious infection, and he died a few days later. The next month, Venizelos surprisingly lost a general election.

At this time, Greece had been at war for eight years straight. World War I was over, but there was no lasting peace. Greece was already fighting against Turkish forces in Asia Minor. Young men had been fighting and dying for years. Farms were empty because there were no hands to work them. The country was tired and facing economic and political problems.

The political parties who supported the King promised peace and good times under the victorious Field Marshal of the Balkan Wars. They said he understood soldiers because he had fought alongside them.

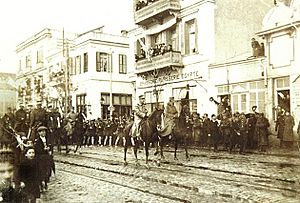

After a public vote where almost 99% of people voted for his return, Constantine came back as king on December 19, 1920. This made many people unhappy, especially the newly freed populations in Asia Minor. The British and French were also very unhappy about Constantine's return.

The new government decided to continue the war. The ongoing campaign in western Anatolia against the Turks started with some success. The Greeks first met disorganized resistance.

In March 1921, despite his health problems, Constantine went to Anatolia to boost the army's morale and personally command the Battle of Kütahya-Eskişehir.

However, a poorly planned idea to capture Kemal's new capital of Ankara failed. Ankara was deep in a dry area where there were few Greeks. The Greek Army was spread too thin and didn't have enough supplies. They were defeated and driven back to the coast in August 1922. After an army revolt by Venizelist officers, who blamed him for the defeat, Constantine gave up his throne again on September 27, 1922. His oldest son, George II, took his place.

Later Life and Passing

Constantine spent the last four months of his life living away from Greece in Italy. He died at 1:30 AM on January 11, 1923, in Palermo, Sicily, from heart failure. His wife, Sophia of Prussia, was never allowed to return to Greece. She was later buried next to her husband in the Russian Church in Florence.

After he became king again, George II arranged for the bodies of his family members who died in exile to be brought back to Greece. In November 1936, a big religious ceremony brought all the living royal family members together for six days. Constantine's body was buried at the royal burial ground at Tatoi Palace, where he rests today.

Family Life and Children

As the Crown Prince of Greece, Constantine married Princess Sophia of Prussia on October 27, 1889, in Athens. Sophia was a granddaughter of Queen Victoria and the sister of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany. They had six children. All three of their sons later became kings of Greece. Their oldest daughter, Helen, married Crown Prince Carol of Romania. Their second daughter married the 4th Duke of Aosta. Their youngest child, Princess Katherine, married a British commoner.

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| King George II | 20 July 1890 | 1 April 1947 | married Princess Elisabeth of Romania |

| King Alexander | 1 August 1893 | 25 October 1920 | married Aspasia Manos (also known as Princess Alexander of Greece) |

| Princess Helen | 2 May 1896 | 28 November 1982 | married Crown Prince Carol of Romania, who later became King of Romania |

| King Paul | 14 December 1901 | 6 March 1964 | married Princess Frederika of Hanover |

| Princess Irene | 13 February 1904 | 15 April 1974 | married Prince Aimone, Duke of Aosta |

| Princess Katharine | 4 May 1913 | 2 October 2007 | married Major Richard Brandram MC |

Legacy and Cultural Impact

Constantine remained a hero for his supporters, especially those on the conservative side, for many years after he died. However, today, the legacy of Venizelos is often more recognized.

In popular culture, a royalist slogan still exists: "psomí, elia ke Kotso Vasiliá" which means "bread, olives and King Constantine." This phrase was popular during a time when Allied ships blocked southern Greece (1916-1917), causing people to go hungry.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Constantino I de Grecia para niños

In Spanish: Constantino I de Grecia para niños