Constantine XI Palaiologos facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Constantine XI Palaiologos |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |||||

15th-century portrait of Constantine XI (from a 15th-century codex containing a copy of the Extracts of History by Joannes Zonaras)

|

|||||

| Byzantine emperor | |||||

| Reign | 6 January 1449 – 29 May 1453 | ||||

| Predecessor | John VIII Palaiologos | ||||

| Despot of the Morea | |||||

| Reign | 1 May 1428 – March 1449 | ||||

| Predecessor | Theodore II Palaiologos (alone) | ||||

| Successor | Demetrios and Thomas Palaiologos | ||||

| Co-rulers | Theodore II Palaiologos (1428–1443) Thomas Palaiologos (1428–1449) |

||||

| Born | 8 February 1405 Constantinople, Byzantine Empire |

||||

| Died | 29 May 1453 (aged 48) Constantinople, Byzantine Empire |

||||

| Spouse |

Theodora Tocco

(m. 1428; died 1429)Caterina Gattilusio

(m. 1441; died 1442) |

||||

|

|||||

| Dynasty | Palaiologos | ||||

| Father | Manuel II Palaiologos | ||||

| Mother | Helena Dragaš | ||||

| Religion | Orthodox | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos (born February 8, 1405 – died May 29, 1453) was the very last Byzantine emperor. He ruled from 1449 until his death in battle during the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. His death marked the final end of the Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire. This empire had started way back in 330 AD when Constantine the Great made Constantinople the new capital of the Roman Empire.

Constantine was the fourth son of Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos and Helena Dragaš. Helena was the daughter of a Serbian ruler named Konstantin Dejanović. We don't know much about Constantine's early life. But from the 1420s, he showed he was a very skilled general. People who knew him said he was mostly a soldier.

However, Constantine was also a good leader. His older brother, Emperor John VIII Palaiologos, trusted him a lot. John made Constantine a regent (someone who rules for the emperor) twice. This happened when John traveled away from Constantinople in 1423–1424 and 1437–1440.

In 1427–1428, Constantine and John defended the Morea (which is the Peloponnese in Greece) from an attack. In 1428, Constantine became a Despot of the Morea. He ruled this area with his brothers Theodore and Thomas. Together, they took back almost all of the Peloponnese for the first time in over 200 years. They also rebuilt the old Hexamilion wall to protect the area. Constantine even led a military campaign into Central Greece and Thessaly in 1444–1446. He tried to expand Byzantine rule there, but it didn't last.

In 1448, Emperor John VIII died without children. Constantine was his chosen successor. So, on January 6, 1449, Constantine was made emperor. His short time as emperor was filled with three main problems. First, he had no children, so there was no clear heir. His friend George Sphrantzes tried to find him a wife, but Constantine died without marrying again.

Second, there was a big religious disagreement in his small empire. Constantine and John VIII both thought that the Orthodox and Catholic Churches needed to unite. They hoped this would bring military help from Catholic Europe. But many people in the empire were against this idea.

Finally, the biggest problem was the growing Ottoman Empire. By 1449, the Ottomans completely surrounded Constantinople. In April 1453, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II attacked Constantinople. He had a huge army, maybe 80,000 soldiers. The city's defenders were much fewer, perhaps less than 8,000. But Constantine refused to leave Constantinople. He stayed to defend the city. On May 29, Constantinople fell. Constantine died that same day. Most stories say he led a final charge against the Ottomans and died fighting.

Constantine was the last Christian ruler of Constantinople. His bravery during the city's fall made him a legendary figure in history and Greek stories. Some people believed that Constantinople, the "New Rome," was founded by a Constantine and lost by another Constantine. This was like "Old Rome" being founded by Romulus and lost by another Romulus, Romulus Augustulus. In Greek folklore, he became known as the Marble Emperor. This legend says Constantine didn't die. An angel saved him and turned him into marble. He is hidden under the Golden Gate of Constantinople, waiting for God's call to wake up and take back the city and the old empire.

Contents

Early Life and Military Career

Family and Background

Constantine Dragases Palaiologos was born on February 8, 1405. He was the fourth son of Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos, who ruled from 1391 to 1425. Manuel was the eighth emperor of the Palaiologos family. Constantine's mother was Helena Dragaš, who gave him his second last name. She was the daughter of a Serbian ruler named Konstantin Dejanović. Constantine was called Porphyrogénnētos, meaning "born in the purple." This special title was given to sons born to a ruling emperor inside the imperial palace.

Manuel ruled a Byzantine Empire that was getting smaller and weaker. The empire began to fall apart after the Seljuk Turks arrived in Anatolia in the 11th century. Even though some emperors tried to get parts of Anatolia back, these gains didn't last. Anatolia was the empire's richest area. After losing it, the Byzantine Empire slowly declined. The empire was also badly hurt in 1204 by the Fourth Crusade. Crusaders took Constantinople and formed the Latin Empire.

The Byzantine Empire, led by Michael VIII Palaiologos, took Constantinople back in 1261. But the damage was too great. The empire kept shrinking in the 14th century because of many civil wars. By 1405, the Ottoman Turks had conquered huge areas. They ruled much of Anatolia, Bulgaria, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, and Thessaly. The Byzantine Empire, which once covered the eastern Mediterranean, was now just Constantinople, the Peloponnese, and a few islands. It also had to pay money to the Ottomans.

As the empire got smaller, emperors gave parts of their land to their sons. These sons were called despots. They were meant to defend and govern these areas. Manuel's oldest son, John VIII Palaiologos, was made co-emperor. His second son, Theodore II Palaiologos, became Despot of the Morea. His third son, Andronikos, became Despot of Thessaloniki in 1408. The younger sons, Constantine, Demetrios, and Thomas, stayed in Constantinople. There wasn't enough land left for them.

We don't know much about Constantine's early life. People who knew him admired him. Later writers often said he was brave, adventurous, and good at fighting, riding horses, and hunting. Many stories about Constantine were written after he died. They often praised him a lot. Based on his actions, Constantine seemed more interested in military matters than in politics. But he was also a good administrator. He listened to his advisors on important state issues. We don't have any real pictures of Constantine from his time.

Early Career and Regent Role

After an Ottoman attack on Constantinople failed in 1422, Emperor Manuel II had a stroke. He was paralyzed on one side. He lived for three more years, but Constantine's brother John effectively ran the empire. The city of Thessaloniki was also under attack by the Ottomans. To save it, John gave the city to the Republic of Venice. John hoped to get help from Western Europe. He left Constantinople in November 1423 to visit Venice and Hungary. Manuel had given up on Western help. He even tried to stop John, believing that uniting the churches would only anger the Turks and his own people.

John was impressed by Constantine's actions during the 1422 Ottoman attack. He trusted Constantine more than his other brothers. Constantine was given the title of despot. He was left to rule Constantinople as a regent. With his father Manuel's help, Constantine made a new peace treaty with the Ottoman Sultan Murad II. This treaty saved Constantinople from more Turkish attacks for a while. John returned in November 1424, but he had failed to get help. On July 21, 1425, Manuel died, and John became Emperor John VIII Palaiologos. Constantine was given a small but important piece of land north of Constantinople. This showed that both Manuel II and John trusted him.

After Constantine's good job as regent, John saw him as loyal and capable. Their brother Theodore was unhappy as Despot of the Morea. So, John called Constantine from his land and made him Theodore's successor. Theodore later changed his mind. But John eventually sent Constantine to the Morea as a despot in 1427. The Morea was often threatened by outside forces. In 1423, the Ottomans broke through the old Hexamilion wall and damaged the Morea. The Morea was also threatened by Carlo I Tocco, an Italian ruler from Epirus. He attacked Theodore in 1426 and took land in the Morea.

In 1427, John VIII went to deal with Tocco. He brought Constantine and Sphrantzes with him. On December 26, 1427, the brothers reached Mystras, the capital of the Morea. They went to Glarentza, which Tocco's forces had captured. In a sea battle, Tocco was defeated. He agreed to give up his lands in the Morea. To make peace, Tocco offered his niece, Maddalena Tocco (later called Theodora), to marry Constantine. Her wedding gift was Glarentza and other Morea lands. Glarentza was given to the Byzantines on May 1, 1428. On July 1, Constantine married Theodora.

Despot of the Morea

Ruling the Morea

When Constantine received Tocco's lands, it made the Morea's government more complex. His brother Theodore didn't want to step down as despot. So, for the first time, the despotate was ruled by two imperial family members. Soon after, their younger brother Thomas (who was 19) was also made a third Despot of the Morea. This meant the area was split into three smaller parts. Theodore kept control of Mystras. He gave Constantine lands across the Morea, including the port town of Aigio and areas in the south and west. Constantine made Glarentza his capital. Thomas was given lands in the north and lived in the castle of Kalavryta. During his time as despot, Constantine was brave and energetic, but also careful.

Soon after becoming despots, Constantine and Thomas, with Theodore, tried to capture the important port of Patras. This city was in the northwest of the Morea and ruled by a Catholic Archbishop. Their first attempt failed. Constantine then decided to try again by himself. He told Sphrantzes and John that if he failed, he would go back to his old lands by the Black Sea. Constantine and Sphrantzes believed the Greek people in Patras would support them. They marched to Patras on March 1, 1429, and attacked the city on March 20. The attack lasted a long time. At one point, Constantine's horse was shot, and he almost died. Sphrantzes saved him but was captured. He was released later, almost dead.

After almost two months, the city's defenders agreed to talk in May. The Archbishop went to Italy to get more soldiers. The defenders said if he didn't return by the end of the month, Patras would surrender. Constantine agreed and pulled back his army. On June 1, Constantine returned. Since the Archbishop hadn't come back, Constantine met with the city's leaders on June 4. They accepted him as their new ruler. The Archbishop's castle on a nearby hill held out for another 12 months before giving up.

Constantine taking Patras angered the Pope, the Venetians, and the Ottomans. To calm things down, Constantine sent ambassadors to all three. Sphrantzes went to talk with the Ottoman governor of Thessaly. Sphrantzes succeeded in stopping a Turkish attack. But the threat from the west came true. The Archbishop returned with an army of mercenaries. These mercenaries were not interested in helping him get Patras back. Instead, they attacked and took Glarentza. Constantine had to buy it back for 6,000 gold coins. They also started robbing the Morea's coast. To stop pirates from taking Glarentza, Constantine ordered it to be destroyed. During this hard time, Constantine suffered another loss: Theodora died in November 1429. Constantine was very sad. He first buried her in Glarentza, then moved her to Mystras. When the Archbishop's castle surrendered in July 1430, Patras was fully under Byzantine rule again after 225 years. In November, Sphrantzes was made governor of Patras.

By the early 1430s, Constantine and his younger brother Thomas had brought almost all of the Peloponnese back under Byzantine control. Thomas ended the Principality of Achaea by marrying the daughter of its last prince. When the prince died in 1432, Thomas took control of all his lands. The only parts of the Peloponnese still under foreign rule were a few port towns held by Venice. Sultan Murad II was worried about the Byzantines' successes in the Morea. In 1431, Murad ordered his troops to destroy the Hexamilion wall. This was to remind the despots that they were under the Sultan's power.

Second Time as Regent

In March 1432, Constantine made a new land deal with Thomas. Thomas gave his castle Kalavryta to Constantine, who made it his new capital. In return, Thomas got Elis, which became his new capital. The relationship between the three despots became difficult. Emperor John VIII had no sons. So, it was thought that one of his four living brothers would take the throne. John VIII wanted Constantine to be his successor. Thomas accepted this, but Constantine's older brother Theodore did not like it. The argument between Constantine and Theodore was not solved until late 1436. They agreed that Constantine would return to Constantinople. Theodore and Thomas would stay in the Morea. John needed Constantine in Constantinople because he was leaving for Italy soon. On September 24, 1437, Constantine arrived in Constantinople. He was not made co-emperor, but he was made regent for a second time. This showed that John intended for him to be the next emperor.

John left for Italy in November to attend a church meeting called the Council of Ferrara. He wanted to unite the Eastern and Western churches. Many in the Byzantine Empire were against this. They felt it meant giving up their religious freedom to the Pope. But John thought unity was necessary to get help from the West. John brought a large group to Italy, including the Patriarch of Constantinople. His younger brother Demetrios also came, even though he was against church union. John didn't want to leave Demetrios in the East because he had shown signs of rebellion. Constantine had trusted advisors in Constantinople. His cousin and a skilled statesman stayed with him. His mother Helena and Sphrantzes also advised Constantine. In 1438, Constantine was the best man at Sphrantzes' wedding. He later became the godfather to two of Sphrantzes' children.

While John was away, the Ottomans kept the peace. Only once did trouble seem to start. In early 1439, Constantine wrote to his brother in Italy. He reminded the Pope that the Byzantines were promised two warships. Constantine hoped the ships would leave Italy soon. He believed Murad II was planning a big attack on Constantinople. The ships were not sent. But Constantinople was not in danger. Murad's army focused on taking a city in Serbia.

In June 1439, the council in Florence, Italy, announced that the churches were reunited. John returned to Constantinople on February 1, 1440. Constantine and Demetrios welcomed him with a big ceremony. But the news of the union made many people angry. They felt John had betrayed their faith. Many feared the union would make the Ottomans suspicious. Constantine agreed with his brother about the union. He believed that if giving up some church independence meant Westerners would help save Constantinople, it was worth it.

Second Marriage and Ottoman Threats

Constantine stayed in Constantinople for the rest of 1440. He wanted to find a new wife. It had been over ten years since Theodora died. He chose Caterina Gattilusio, the daughter of a Genoese lord from the island of Lesbos. Sphrantzes went to Lesbos in December 1440 to arrange the marriage. In late 1441, Constantine sailed to Lesbos with Sphrantzes. He married Caterina in August. In September, he left Lesbos, leaving Caterina with her father. He then traveled to the Morea.

When he returned to the Morea, Constantine saw that Theodore and Thomas had ruled well. He thought he could help the empire more if he was closer to the capital. His younger brother Demetrios ruled Constantine's old land near Mesembria. Constantine thought he and Demetrios could switch places. Constantine would get his old land back, and Demetrios would get Constantine's lands in the Morea. Constantine sent Sphrantzes to suggest this to Demetrios and Sultan Murad II. By this time, the Sultan had to approve any such changes.

By 1442, Demetrios wanted the imperial throne. He had made a deal with Murad and raised an army. He said he was fighting for those who opposed the church union. He declared war on John. When Sphrantzes reached Demetrios with Constantine's offer, Demetrios was already preparing to march on Constantinople. He was so dangerous that John called Constantine from the Morea to help defend the city. In April 1442, Demetrios and the Ottomans began their attack. In July, Constantine left the Morea. On the way, he met his wife at Lesbos. They sailed to Lemnos, where an Ottoman blockade trapped them for months. Caterina became sick and died in August. She was buried on Lemnos. Constantine didn't reach Constantinople until November. By then, the Ottoman attack had been stopped. Demetrios was briefly put in prison. In March 1443, Sphrantzes was made governor of Selymbria in Constantine's name. From Selymbria, they could watch Demetrios. In November, Constantine gave Selymbria to Theodore. Theodore had left his position as Despot of the Morea. This made Constantine and Thomas the only Despots of the Morea. Constantine also gained Mystras, the capital of the despotate.

Despot at Mystras

With Theodore and Demetrios gone, Constantine and Thomas wanted to make the Morea stronger. By this time, the Morea was a center for Byzantine culture. It felt more hopeful than Constantinople. Artists and scientists had moved there. Churches, monasteries, and mansions were still being built. The two brothers hoped to make the Morea a safe and self-sufficient area. A philosopher named Gemistus Pletho, who worked for Constantine, said that Mystras and the Morea could become a "New Sparta." This would be a strong Greek kingdom.

One of their plans was to rebuild the Hexamilion wall. The Turks had destroyed it in 1431. Together, they completely rebuilt the wall by March 1444. This project impressed many people, even the Venetian lords in the Peloponnese. The Venetians had refused to help pay for it. The rebuilding cost a lot of money and manpower. Many landowners in the Morea had fled to Venetian lands to avoid paying. Others had rebelled before being forced to help. Constantine tried to win the loyalty of the landowners. He gave them more land and special rights. He also held local athletic games for young people.

In the summer of 1444, Constantine attacked the Latin Duchy of Athens. This duchy was his neighbor to the north and paid tribute to the Ottomans. Constantine was encouraged by news that a crusade had started from Hungary in 1443. Constantine quickly captured Athens and Thebes. This forced the Duke of Athens to pay tribute to Constantine instead of the Ottomans. Taking Athens back was seen as a great achievement. One of Constantine's advisors compared him to the ancient Athenian general Themistocles.

However, the crusading army was destroyed by the Ottoman army in the Battle of Varna on November 10, 1444. But Constantine was not stopped. His first campaign had been very successful. He also received help from Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy, who sent him 300 soldiers. With these soldiers, Constantine raided central Greece. He went as far north as the Pindus mountains in Thessaly. The local people welcomed him as their new ruler. As Constantine's campaign continued, one of his governors also attacked Thessaly. He took the town of Lidoriki from the Ottomans. The townspeople were so happy that they renamed the town in his honor.

Sultan Murad II was tired of Constantine's successes. In 1446, Murad II, along with the Duke of Athens, marched on the Morea. His army might have had as many as 60,000 men. Despite the huge number of Ottoman troops, Constantine refused to give up his gains in Greece. He prepared for battle. The Ottomans quickly took back control of Thessaly. Constantine and Thomas gathered at the Hexamilion wall. The Ottomans reached the wall on November 27. Constantine and Thomas were determined to hold the wall. They brought all their available soldiers, maybe 20,000 men, to defend it. The wall might have held against the large Ottoman army in normal times. But Murad had brought cannons. By December 10, the wall was in ruins. Most of the defenders were killed or captured. Constantine and Thomas barely escaped. Murad sent his general to devastate Constantine's lands. Although Mystras was not captured, Murad only wanted to scare the people. The Turks left the Peloponnese destroyed and empty. Constantine and Thomas had to accept Murad as their ruler. They had to pay him tribute and promise never to rebuild the Hexamilion wall.

Reign as Emperor

Becoming Emperor

Theodore, the former Despot of the Morea, died in June 1448. On October 31 of that same year, John VIII Palaiologos died in Constantinople. Among his living brothers, Constantine was the most popular. This was true in both the Morea and the capital. Everyone knew that John wanted Constantine to be his successor. In the end, his mother Helena Dragaš, who also preferred Constantine, made the final decision. Both Thomas and Demetrios rushed to Constantinople. Demetrios certainly wanted the throne. Many people supported Demetrios because he was against the church union. But Helena kept her right to be regent until Constantine arrived. She stopped Demetrios from taking the throne. Thomas accepted Constantine's appointment. Demetrios was overruled, though he later said he accepted Constantine as emperor. Soon after, Sphrantzes told Sultan Murad II, who also accepted the appointment on December 6, 1448. With the succession settled peacefully, Helena sent two messengers to the Morea. They were to declare Constantine emperor and bring him to the capital. Thomas also went with them.

In a small ceremony at Mystras, perhaps in a church or the Despot's Palace, on January 6, 1449, Constantine was given the title of "Basileus" of the Romans. He was not given a crown. Instead, Constantine put a smaller imperial hat on his head himself. Emperors were usually crowned in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. But there were times when smaller, local ceremonies happened. For example, centuries ago, Manuel I Komnenos was given the title of emperor by his dying father in Cilicia. Constantine's great-grandfather, John VI Kantakouzenos, was declared emperor in Thrace. Both Manuel I and John VI were careful to have the traditional coronation in Constantinople later. But in Constantine's case, this never happened. Both Constantine and the Patriarch of Constantinople, Gregory III Mammas, supported the Union of the Churches. If Gregory had crowned Constantine, it might have caused the anti-unionists in the capital to rebel. Constantine's rise to emperor was debated. He was accepted because of his family line. But his lack of a full coronation and his support for the church union hurt how people saw him.

Constantine believed his declaration at Mystras was enough. He thought it gave him all the rights of a true emperor. In his first known imperial document from February 1449, he called himself "Constantine Palaiologos in Christ true Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans." Constantine arrived in Constantinople on March 12, 1449, on a Catalan ship.

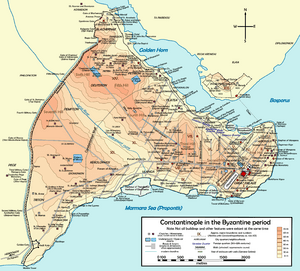

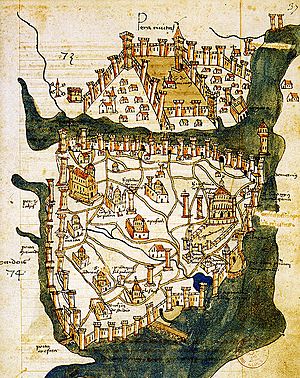

Constantine was well prepared to be emperor. He had been regent twice and ruled many areas in the shrinking empire. By Constantine's time, Constantinople was not as grand as it used to be. The city never fully recovered from the 1204 attack by the crusaders. In the 15th century, Constantinople was more like a rural area with small towns. Many churches and palaces were abandoned. The emperors lived in the Palace of Blachernae, closer to the city walls. The city's population had dropped a lot. By the time Constantine became emperor, only about 50,000 people lived there.

Early Challenges as Emperor

One of Constantine's biggest worries was the Ottomans. One of his first actions as emperor was to make a truce with Murad II. He sent an ambassador to the sultan. The ambassador succeeded, and the truce also included Constantine's brothers in the Morea. This protected the province from more Ottoman attacks. To get his rebellious brother Demetrios away from the capital, Constantine made Demetrios his replacement as Despot of the Morea. Demetrios would rule with Thomas. Demetrios got Constantine's old capital, Mystras. Thomas ruled other parts of the despotate.

Constantine tried to talk with the anti-unionists in the capital. These were people who opposed the church union. They had formed a group to go against Patriarch Gregory III. Constantine was not extreme about the union. He just thought it was needed for the empire to survive. The anti-unionists thought this argument was weak. They believed help would come from God, not from a Western crusade.

Another big concern was that neither Constantine nor his brothers had sons. This meant there was no one to continue the imperial family. In February 1449, Constantine sent a messenger to Alfonso V of Aragon and Naples. He wanted military help against the Ottomans and a marriage alliance. The plan was for Constantine to marry Alfonso's niece, Beatrice of Coimbra. But this alliance failed. In October 1449, Constantine sent Sphrantzes to the east. He was to visit the Empire of Trebizond and the Kingdom of Georgia to find a suitable bride. Sphrantzes traveled for almost two years.

While at the court of Emperor John IV of Trebizond, Sphrantzes learned that Murad II had died. John IV thought this was good news. But Sphrantzes was more worried. The old sultan had given up on conquering Constantinople. His young son and successor, Mehmed II, was ambitious and energetic. Sphrantzes thought that Mehmed might not attack Constantinople if Constantine married Murad II's widow, Mara Branković. Constantine liked this idea when he got Sphrantzes' report in May 1451. He sent messengers to Serbia, where Mara had returned. Many of Constantine's advisors were against this idea. They didn't trust the Serbians. In the end, Mara didn't want to remarry. She had promised to live a life of purity after Murad II's death. Sphrantzes then decided a Georgian bride would be best. He returned to Constantinople in September 1451 with a Georgian ambassador. Constantine thanked Sphrantzes. They agreed that Sphrantzes would go back to Georgia in spring 1452 to arrange a marriage. But tensions with the Ottomans grew, so Sphrantzes never went back to Georgia.

On March 23, 1450, Helena Dragaš died. She was highly respected and deeply mourned. Philosophers and future patriarchs wrote speeches praising her. Helena's death left Constantine unsure who to trust most. His advisors often disagreed with him and each other. The most powerful person at court was Loukas Notaras. He was a skilled statesman and the commander of the navy. Notaras believed Constantinople's strong defenses would stop any attack. He thought this would give Western Christians time to help. Constantine was likely influenced by Notaras's ideas. Sphrantzes was promoted to a high position. This gave him close access to the emperor. Sphrantzes was more careful about the Ottomans than Notaras. He thought Notaras risked making the new sultan angry.

Looking for Allies

After Murad II died, Constantine quickly sent messengers to the new Sultan Mehmed II. He wanted to arrange a new truce. Mehmed supposedly treated Constantine's messengers with great respect. He swore by his religion that he would live in peace with the Byzantines. But Constantine was not convinced. He suspected Mehmed's mood could change. To prepare for a possible Ottoman attack, Constantine needed allies. The most powerful possible allies were in the West.

The closest potential ally was Venice. They had a large trading colony in Constantinople. But the Venetians were not always trustworthy. In his first few months as emperor, Constantine raised taxes on Venetian goods. The imperial treasury was almost empty, and money was needed. In August 1450, the Venetians threatened to move their trade to another port, perhaps one controlled by the Ottomans. Even though Constantine wrote to the Doge of Venice, Francesco Foscari, the Venetians were not convinced. They signed a formal treaty with Mehmed II in 1451. To annoy the Venetians, Constantine tried to make a deal with the Republic of Ragusa in 1451. He offered them a place to trade in Constantinople with lower taxes. But Ragusa could offer little military help.

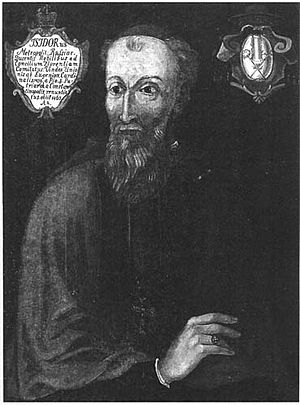

Most kingdoms in Western Europe were busy with their own wars. The crushing defeat at the Battle of Varna had reduced the desire for crusades. The news that Murad II had died and was replaced by his young son also made Western Europeans feel too safe. For the Pope, the Union of the Churches was more important than the Ottoman threat. In August 1451, Constantine's messenger arrived in Rome. He delivered a letter to Pope Nicholas V. The letter explained the anti-unionists' objections in Constantinople. Constantine hoped the Pope would understand his difficulties. The letter suggested a new church council in Constantinople, with equal numbers from both churches. On September 27, Nicholas V replied. He said Constantine had to try harder to convince his people. He also said that military aid from the West depended on full acceptance of the union. The Pope's name had to be mentioned in Greek churches, and Gregory III had to be made patriarch again. This ultimatum was a setback for Constantine. He had tried his best to enforce the union without causing riots. The Pope seemed to ignore the anti-unionists' feelings. Nicholas V sent a papal legate, Cardinal Isidore of Kiev, to Constantinople. He was to help Constantine enforce the union. But Isidore didn't arrive until October 1452, when the city faced bigger problems.

Dealing with Mehmed II

A great-grandson of Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I, named Orhan Çelebi, lived as a hostage in Constantinople. Besides Mehmed II, Orhan was the only other living male member of the Ottoman royal family. This made him a possible rival for the sultan's throne. Mehmed had agreed to pay yearly for Orhan to be kept in Constantinople. But in 1451, Constantine sent a message to the sultan. He complained that the payment was not enough. He hinted that if more money wasn't paid, Orhan might be set free. This could start an Ottoman civil war. Constantine's father had used this strategy before. But it was very risky. Mehmed's chief minister received the message and was shocked. He thought the Byzantines were foolish. This minister had often helped the Byzantines keep peace with the Ottomans. But his influence over Mehmed was limited.

Constantine and his advisors had completely misunderstood the new sultan's determination. Throughout his short reign, Constantine and his advisors could not create a good foreign policy towards the Ottoman Empire. Constantine mostly continued what his predecessors did. He tried to prepare Constantinople for attack. But he also switched between begging and challenging the Ottomans. Constantine's advisors didn't know much about the Ottoman court. They disagreed on how to deal with the Ottoman threat. As Constantine listened to different advisors, his policy was not clear. This led to disaster.

Mehmed II believed Constantine had broken their 1449 truce. He quickly took back the small favors he had given the Byzantines. The threat of releasing Orhan gave Mehmed a reason to focus all his efforts on taking Constantinople. This had been his real goal since he became sultan. Mehmed believed that conquering Constantinople was vital for the Ottoman state to survive. By taking the city, he would stop any future crusade from using it as a base. He would also prevent it from falling into the hands of a more dangerous rival. Also, Mehmed was very interested in ancient Greek and Roman history. His childhood heroes were figures like Achilles and Alexander the Great.

Mehmed began preparations right away. In the spring of 1452, work started on the Rumelihisarı castle. It was built on the western side of the Bosporus strait. This was opposite the existing Anadoluhisarı castle on the eastern side. With both castles, Mehmed could control sea traffic in the Bosporus. He could block Constantinople by both land and sea. Constantine was horrified. He protested that Mehmed's grandfather had asked Emperor Manuel II's permission before building the eastern castle. He reminded the sultan of their truce. Based on his actions in the Morea, Constantine was clearly against the Turks. His appeals to Mehmed were just a way to buy time. Mehmed replied that the area he built the fortress on was empty. He said Constantine owned nothing outside Constantinople's walls.

Panic spread in Constantinople. The Rumelihisarı was finished in August 1452. It was meant to block Constantinople and be the base for Mehmed's conquest. To build the new castle, some local churches were torn down. This angered the local Greek people. Mehmed had them killed. The Ottomans also sent animals to graze on Byzantine farmland. When Greek farmers protested, Mehmed sent troops to attack them. About forty were killed. Outraged, Constantine officially declared war on Mehmed II. He closed Constantinople's gates and arrested all Turks inside the city. But seeing how pointless this was, Constantine changed his mind three days later. He set the prisoners free. Later, during Mehmed's siege, some Italian ships were captured, and their crews executed. Constantine then reluctantly ordered the execution of all Turks inside Constantinople.

Constantine began to prepare for a blockade or a siege. He gathered supplies and repaired Constantinople's walls. Manuel Palaiologos Iagros, one of the envoys who had made Constantine emperor, was in charge of fixing the strong walls. This project was finished in late 1452. Constantine sent more urgent requests for help to the West. In late 1451, he sent a message to Venice. He said that unless they sent help at once, Constantinople would fall. The Venetians felt bad for the Byzantines. But they replied in February 1452 that they could send armor and gunpowder. However, they had no troops to spare because they were fighting in Italy. In November 1452, the Ottomans sank a Venetian trading ship in the Bosporus. They executed the crew for not paying a new toll. This changed the Venetian attitude. They were now also at war with the Ottomans. Desperate for help, Constantine sent pleas to his brothers in the Morea. He also asked Alfonso V of Aragon and Naples for help. He promised Alfonso the island of Lemnos if he brought aid. The Hungarian warrior John Hunyadi was invited. He was promised land if he came. The Genoese on the island of Chios were also asked for help. They were promised payment. Constantine received little real help.

Religious Disagreements in Constantinople

Most importantly, Constantine sent many appeals for help to Pope Nicholas V. The Pope was sympathetic. But he believed the papacy could not help the Byzantines unless they fully accepted the Union of the Churches. Also, he knew the papacy alone could not do much against the strong Ottoman Turks. This was similar to Venice's response. Venice promised military help only if others in Western Europe also came to Constantinople's defense. On October 26, 1452, Pope Nicholas V's representative, Isidore of Kiev, arrived in Constantinople. He came with the Latin Archbishop of Mytilene, Leonard of Chios. They brought a small force of 200 archers. These soldiers made little difference in the coming battle. But the people of Constantinople probably appreciated them more than the reason for Isidore's visit: to strengthen the Union of the Churches. Their arrival made the anti-unionists very angry.

Constantine and John VIII before him had badly misjudged how much people opposed the church union. Loukas Notaras managed to calm things down a bit in Constantinople. He explained to a meeting of nobles that the Catholic visit was well-intentioned. He said the soldiers might be just an advance group, and more help might be coming. Many nobles were convinced that they could pay a spiritual price for material rewards. They thought if they were saved from immediate danger, they could think more clearly later. Sphrantzes suggested to Constantine that he name Isidore as the new Patriarch of Constantinople. This was because Gregory III had not been seen for some time. Constantine knew that such an appointment would only anger the anti-unionists more. Once the people of Constantinople realized no more immediate help was coming from the Pope, they rioted.

Leonard of Chios told the emperor that he was too soft on the anti-unionists. He urged Constantine to arrest their leaders and push harder for the church union. Constantine disagreed. He thought arresting them would make them martyrs. Instead, Constantine called the leaders of the anti-unionist group to the imperial palace on November 15, 1452. He asked them again to write down their objections to the union. On November 25, the Ottomans sank another Venetian trading ship with cannon fire. This event captured the Byzantines' attention. It united them in fear and panic. As a result, the anti-unionist cause slowly faded. On December 12, a Catholic church service was held in the Hagia Sophia. It mentioned the names of the Pope and Patriarch Gregory III. Constantine and his court were there, as were many citizens.

Final Preparations for Siege

Constantine's brothers in the Morea could not help him. Mehmed had ordered his general to invade and devastate the Morea again in October 1452. This kept the two despots busy. Constantine then had to rely on Venice, the Pope, and Alfonso V of Aragon and Naples. Venice had been slow to act. But the Venetians in Constantinople acted immediately when the Ottomans sank their ships. The Venetian leader in Constantinople called an emergency meeting. Constantine and Cardinal Isidore also attended. Most Venetians voted to stay in Constantinople and help defend the city. They agreed that no Venetian ships would leave the harbor. This decision by the local Venetians had a much greater effect on the Venetian government than Constantine's pleas.

In February 1453, the Doge of Venice ordered warships and soldiers to be prepared. They were to head for Constantinople in April. He sent letters to the Pope, Alfonso V, the King of Hungary, and the Holy Roman Emperor. He told them that unless Western Christianity acted, Constantinople would fall. The increase in diplomatic activity was impressive. But it came too late to save Constantinople. Getting the papal-Venetian fleet ready took longer than expected. The Venetians had misjudged the time they had. Messages took at least a month to travel from Constantinople to Venice. Emperor Frederick III's only response was a letter to Mehmed II. He threatened the sultan with an attack from all of Western Christendom. This would happen unless the sultan destroyed the Rumelihisarı castle and gave up his plans for Constantinople. Constantine kept hoping for help. He sent more letters in early 1453 to Venice and Alfonso V. He asked not only for soldiers but also for food. His people were starting to suffer from the Ottoman blockade. Alfonso responded by quickly sending a ship with supplies.

Throughout the long winter of 1452–1453, Constantine ordered the people of Constantinople to repair the city's strong walls. They also gathered as many weapons as they could. Ships were sent to the islands still under Byzantine rule to get more supplies. The defenders grew worried. News reached the city about a huge cannon at the Ottoman camp. It was built by a Hungarian engineer. Loukas Notaras was given command of the sea walls along the Golden Horn. Various members of the Palaiologos and Kantakouzenos families were put in charge of other positions. Many foreign residents, especially Venetians, offered their help. Constantine asked them to man the walls. This would show the Ottomans how many defenders they faced. When the Venetians offered to guard four of the city's land gates, Constantine accepted. He gave them the keys. Some Genoese people in the city also helped. In January 1453, a famous Genoese soldier named Giovanni Giustiniani arrived voluntarily. He brought 700 soldiers. Constantine made Giustiniani the general commander for the land walls. Giustiniani was promised the island of Lemnos as a reward. In addition to the limited Western help, Orhan Çelebi, the Ottoman rival held hostage in the city, and his soldiers also helped defend the city.

On April 2, 1453, Mehmed's first troops arrived outside Constantinople. They began setting up camp. On April 5, the sultan himself arrived with his army. He camped within firing range of the city's Gate of St. Romanus. The bombardment of the city walls began almost immediately on April 6. Most estimates say that 6,000–8,500 soldiers defended Constantinople's walls in 1453. About 5,000–6,000 of these were Greeks, mostly untrained militia. Another 1,000 Byzantine soldiers were kept as reserves inside the city. Mehmed's army was much larger than the Christian defenders. His forces might have been as many as 80,000 men, including about 5,000 elite janissaries. Even with this, Constantinople's fall was not certain at first. The strength of the walls made the Ottoman numbers less important at first. Under other circumstances, the Byzantines and their allies could have survived until help arrived. But the Ottoman use of cannons greatly sped up the siege.

Fall of Constantinople

The Siege Begins

An Ottoman fleet tried to enter the Golden Horn. Meanwhile, Mehmed began firing cannons at Constantinople's land walls. Constantine had expected this. He had built a huge chain across the Golden Horn to block the fleet. The chain was only lifted briefly a few days after the siege began. This was to let three Genoese ships sent by the Pope and a large food ship from Alfonso V pass. The arrival of these ships on April 20 was a big victory for the Christians. It greatly boosted their morale. The ships carried soldiers, weapons, and supplies. They had passed Mehmed's scouts unnoticed. Mehmed ordered his admiral to capture the ships at all costs. A naval battle began between the smaller Ottoman ships and the large Western ships. Mehmed rode his horse into the water, shouting commands. The Ottoman cannons were too low to damage the Western ships. As the sun set, the wind returned. The ships passed through the Ottoman blockade, helped by three Venetian ships.

The sea walls were weaker than Constantinople's land walls. Mehmed was determined to get his fleet into the Golden Horn. He needed a way around Constantine's chain. On April 23, the defenders of Constantinople saw something amazing. The Ottoman fleet was being pulled over land. They were using a huge series of tracks built on Mehmed's orders. The ships were pulled across the hill behind Galata, a Genoese colony. The Venetians tried to attack the ships and set them on fire, but they failed.

As the siege continued, it became clear that there were not enough defenders. They couldn't man both the sea walls and the land walls. Also, food was running out. Food prices rose, and many poor people began to starve. Constantine ordered the Byzantine soldiers to collect money from churches, monasteries, and private homes. This money was to buy food for the poor. Precious metal objects from churches were taken and melted down. Constantine promised the clergy he would repay them four times over if they won. The Ottomans constantly fired cannons at the city's outer walls. They eventually made a small hole that exposed the inner defenses. Constantine grew more and more worried. He sent messages begging the sultan to leave. He promised any amount of tribute. But Mehmed was determined to take the city.

For Constantine, leaving Constantinople was unthinkable. He didn't even reply to the sultan's offer to surrender. Some days later, Mehmed sent a new messenger to the citizens of Constantinople. He urged them to surrender and save themselves from death or slavery. The sultan said he would let them live as they were, in exchange for yearly tribute. Or, he would let them leave the city unharmed with their belongings. Some of Constantine's friends and advisors begged him to escape. They said if he escaped, he could start an empire in exile in the Morea. He could continue the war against the Ottomans. But Constantine refused. He didn't want to be remembered as the emperor who ran away.

The only hope the citizens had was news that the Venetian fleet was coming. But a Venetian scout ship returned to the city. It reported that no relief force had been seen. It became clear that the few forces in Constantinople would have to fight the Ottoman army alone. The news that all of Christendom seemed to have abandoned them worried some Venetian and Genoese defenders. Fights broke out between them. Constantine had to remind them that they had bigger enemies. Constantine decided to trust in Christ. If the city fell, it would be God's will.

Final Days and Attack

The Byzantines saw strange and bad signs in the days before the final Ottoman attack. On May 22, there was a lunar eclipse for three hours. This seemed to confirm a prophecy that Constantinople would fall when the moon was shrinking. To encourage the defenders, Constantine ordered that the icon of Mary, the city's protector, be carried through the streets. But the procession stopped when the icon slipped from its frame. Then it started to rain and hail. Carrying out the procession the next day was impossible because a thick fog covered the city.

On May 26, the Ottomans held a war meeting. One general advised Mehmed to make a deal with the Byzantines. He thought Western military aid was coming soon. But another officer urged the sultan to keep fighting. He pointed out that Alexander the Great had conquered much of the world when he was young. Mehmed ordered this officer to ask the soldiers for their opinions. On the evening of May 26, the dome of the Hagia Sophia was lit by a strange light. The Ottomans also saw it from their camp. The Ottomans saw it as a good sign for their victory. The Byzantines saw it as a sign of coming doom. May 28 was calm. Mehmed had ordered a day of rest before his final attack. Citizens who were not working prayed in the streets. On Constantine's orders, icons and holy objects from all churches were carried along the walls. Both Catholic and Orthodox defenders prayed together. Constantine led the procession himself. Giustiniani asked Loukas Notaras to bring his cannons to defend the land walls. Notaras refused. Giustiniani accused Notaras of betrayal. They almost fought before Constantine stepped in.

In the evening, the crowds went to the Hagia Sophia. Orthodox and Catholic Christians prayed together. The fear of doom had united them more than any councils. Cardinal Isidore was there, as was Emperor Constantine. Constantine prayed and asked for forgiveness from all the bishops. Then he received communion at the church's altar. The emperor then left the church. He went to the imperial palace and said goodbye to his household. Then he disappeared into the night. He went to make a final check of the soldiers on the city walls.

Without warning, the Ottomans began their final attack in the early hours of May 29. The service in the Hagia Sophia was interrupted. Men old enough to fight rushed to the walls. Others helped the army inside the city. Waves of Mehmed's troops attacked Constantinople's land walls. They hammered at the weakest section for over two hours. Despite the fierce attack, the defense held firm. Giustiniani led it, supported by Constantine. But unknown to anyone, after six hours of fighting, just before sunrise, Giustiniani was badly wounded.

Giustiniani was too weak. His bodyguards carried him to the harbor. He escaped the city on a Genoese ship. The Genoese troops lost heart when they saw their commander leave. The Byzantine defenders fought on. But the Ottomans soon took control of both the outer and inner walls. About fifty Ottoman soldiers got through one of the gates, the Kerkoporta. It had been left unlocked by a Venetian group the night before. They were the first enemies to enter Constantinople. They raised an Ottoman flag above the wall. The Ottomans stormed through the wall. Many defenders panicked with no way to escape. Constantinople had fallen. Giustiniani died of his wounds on his way home. Loukas Notaras was captured alive but executed shortly after. Cardinal Isidore dressed as a slave and escaped. Orhan, Mehmed's cousin, dressed as a monk to escape. But he was identified and killed.

Death of the Emperor

Constantine died the day Constantinople fell. No one saw his death and survived to tell the story. The Greek historian Michael Critobulus, who later worked for Mehmed, wrote that Constantine died fighting the Ottomans. Later Greek historians agreed. They never doubted that Constantine died as a hero. This idea was never seriously questioned in the Greek world. Most people who wrote about Constantinople's fall, both Christians and Muslims, agree that Constantine died in battle. Only three accounts claim he escaped. According to Critobulus, Constantine's last words were: "The city is fallen and I am still alive."

There were other different stories about Constantine's death. Leonard of Chios, who was captured but escaped, wrote that Constantine lost courage after Giustiniani fled. The emperor begged his young officers to kill him so he wouldn't be captured alive. None of the soldiers were brave enough. When the Ottomans broke through, Constantine fell in the fight. He got up briefly before falling again and being trampled. A Venetian doctor who was there wrote that no one knew if the emperor had died or escaped.

Ottoman accounts all agree that Constantine was killed. One Ottoman writer, who was part of Mehmed's army, wrote a less heroic story. He said Constantine panicked and fled to the harbor to find a ship. On his way, he met some Turkish soldiers. After almost killing one, he was killed. A later Ottoman historian wrote a similar story. He said the emperor's head was cut off by a giant soldier who didn't know who he was. A Venetian who had been captured by the Ottomans gave an account to Alfonso V in 1454. He said Constantine's fate "deserved to be recorded and remembered for all time." He stated that Constantine refused to escape. He preferred to die with his empire. Constantine went to where the fighting was thickest. He threw off his imperial clothes so he wouldn't stand out. He disappeared into the fight, sword in hand. When Mehmed wanted Constantine brought to him, he was told the emperor was dead. A search found his body. His head was cut off and paraded through Constantinople. Then it was sent as a gift to the Sultan of Egypt.

Legacy of Constantine

Historical Importance

Constantine's death marked the end of the Byzantine Empire. This empire's history went back to Constantine the Great's founding of Constantinople in 330. Even as their land became smaller, the Byzantines always called themselves Romaioi (Romans). So, Constantine's death also marked the final end of the Roman Empire, which began with Augustus 1,480 years earlier. The fall of Constantinople also marked the true start of the Ottoman Empire. It ruled much of the eastern Mediterranean until its fall in 1922. Taking Constantinople had been a dream of Islamic armies for centuries. By owning it, Mehmed II and his successors claimed to be the heirs of the Roman emperors.

There is no proof that Constantine ever gave up on the church union. He had worked hard to achieve it. Many of his people had called him a traitor. But he, like many emperors before him, died in agreement with the Church of Rome. Still, Constantine's actions during the Fall of Constantinople and his death fighting the Turks changed how people saw him. Greeks forgot that he might have been a "heretic." Many saw him as a martyr. The Orthodox Church saw his death as making him a hero. In Athens, the capital of Greece, there are two statues of Constantine. One is a huge statue of him on horseback. The other is a smaller statue in the city's main church square. It shows him on foot with a sword. There are no statues of other emperors who were more successful and died peacefully.

Historians who study Constantine and the fall of Constantinople often show him and his advisors as victims. There are three main books about Constantine's life. The first was written in 1892. It was meant to be propaganda for Greece. It showed Constantine as a sad victim of events he couldn't control. The second major book, from 1965, also shows Constantine as a tragic figure. It says he did everything to save his empire. But it also partly blames him for making Mehmed II angry. The third major book, from 1992, looks at Constantine's whole life. It analyzes the challenges he faced as emperor and as Despot of the Morea. This book puts less focus on individuals. Constantine is still shown as mostly tragic.

A less positive view of Constantine came out in 2019. This historian found no evidence that Constantine was a great leader or soldier. He thought Constantine was not good at diplomacy. He also couldn't inspire his people to reach his goals. This historian criticized the earlier book for being unbalanced. He pointed out that Constantine's reconquest of the Morea was mostly through marriages, not military wins. While much of this work uses old sources, some of his negative ideas are guesses. He suggests Constantine's campaigns in the Morea made it "easier prey for the Turks." But actual events don't fully support this.

Legends of Constantine's Family

Constantine's two marriages were short. He tried to find a third wife before Constantinople fell. But he died unmarried and without children. His closest living relatives were his brothers Thomas and Demetrios. Despite this, a story spread that Constantine had left a wife and several daughters. The earliest record of this idea is in a letter from July 1453. In a later book, the story grew. It said Mehmed II supposedly harmed and killed the empress and Constantine's daughters after his victory. It also spoke of an imaginary son of Constantine who escaped. This story might have spread through a Russian tale from the late 15th or early 16th century. A 16th-century French writer said Mehmed kept the empress in his harem.

The story of Constantine's supposed family continued in modern Greek folklore. One story, told until the 20th century, said Constantine's empress was six months pregnant when Constantinople fell. A son was born to her while Mehmed was fighting in the north. The empress raised the boy. He learned about Christianity and Greek. But as an adult, he became Muslim and eventually became sultan. This meant all Ottoman sultans after him would have been Constantine's descendants. This story is fictional. But it might have a tiny bit of truth. A grandson of Constantine's brother Thomas, Andreas Palaiologos, lived in Constantinople in the 16th century. He became Muslim and worked for the Ottoman court.

Another folk story said Constantine's empress locked herself in the imperial palace after Mehmed's victory. The Ottomans couldn't break in. So Mehmed had to agree to three things. All coins minted by the sultans in the city would have Constantinople or Constantine's name. There would be a street only for Greeks. And Christian dead would get Christian funerals.

Sad Songs and the Marble Emperor

The Fall of Constantinople shocked Christians across Europe. In Orthodox Christianity, Constantinople and the Hagia Sophia became symbols of lost greatness. In a Russian tale, Constantinople (the New Rome) was founded by Constantine the Great. Its loss under an emperor with the same name was seen as fate. Just like Old Rome was founded by Romulus and lost under Romulus Augustulus.

A Greek scholar who fled to Italy wrote a text called Monodia. In it, he mourns the fall of Constantinople and Constantine Palaiologos. He calls Constantine "a ruler more perceptive than Themistocles, more fluent than Nestor, wiser than Cyrus, more just than Rhadamanthus and braver than Hercules".

A Greek poem from 1453, whose author is unknown, blames Constantine's bad luck on his decision to destroy Glarentza in the 1420s. The author says all of Constantine's other troubles were because of Glarentza. Even so, the author believed Constantine was not to blame for Constantinople's fall. He had done what he could. He relied on help from Western Europe that never came.

The Marble Emperor Legend

In the late 15th century, a legend began among the Greeks. It said Constantine had not actually died. He was just asleep, waiting for a call from heaven to save his people. This became the legend of the "Marble Emperor" (Greek: Marmaromenos Vasilias). This means "Emperor/King turned into Marble." The legend says Constantine Palaiologos, the hero of Constantinople's last Christian days, was saved. An angel turned him into marble just before he was killed. The angel then hid him in a secret cave under the Golden Gate of Constantinople. This was where emperors used to march during triumphs. He waits there for the angel's call to wake up and take back the city. The Turks later walled up the Golden Gate. The story says this was to stop Constantine's return. When God wants Constantinople to be restored, the angel will come down. It will bring Constantine back to life. It will give him the sword he used in the final battle. Then Constantine will march into his city and restore his fallen empire. He will drive the Turks far away to their legendary homeland. The legend says Constantine's return will be announced by a loud bellowing ox.

The story is shown in 17 pictures in a 1590 book by a Cretan painter. The pictures show the emperor sleeping under Constantinople, guarded by angels. He is crowned again in the Hagia Sophia. He enters the imperial palace. Then he fights many battles against the Turks. After his victories, Constantine prays in a city called Kayseri. He marches to Palestine and returns to Constantinople in triumph. In Jerusalem, Constantine gives his crown and the True Cross to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Finally, he travels to Calvary, where he dies, his mission complete. In the last picture, Constantine is buried in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

In 1625, an English diplomat asked the Ottoman government for permission. He wanted to remove some stones from the walled-up Golden Gate. He wanted to send them to a friend who collected old things. He was refused. The diplomat noticed that the Turks had a strange fear of the gate. He wrote that the statues on it were enchanted. If they were destroyed, a "great alteration" would happen to the city.

The prophecy of the Marble Emperor lasted until the Greek War of Independence in the 19th century and beyond. It grew stronger when the King of Greece named his first son Constantine in 1868. His name echoed the old emperors. It showed his connection not just to the new Greek kings, but to the Byzantine emperors before them. When he became King Constantine I of Greece, many in Greece called him Constantine XII. His capture of Thessaloniki from the Turks in 1912 seemed to show the prophecy was coming true. People believed Constantinople was his next goal. When Constantine was forced to step down in 1917, many thought he was unfairly removed before finishing his sacred destiny. The hope of capturing Constantinople finally ended with the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War in 1922.

Regnal Number

Constantine Palaiologos is usually called the eleventh emperor with that name. So, he is known as Constantine XI. This number helps tell him apart from other rulers with the same name. But Roman emperors never used these numbers. Even though there were many emperors named Michael, Leo, John, or Constantine in the Middle Ages, the Byzantine Empire never started this practice. Instead, they used nicknames or family names to tell emperors apart. The modern numbering of Byzantine emperors was invented by historians.

The name Constantine was very popular. It connected an emperor to the founder of Constantinople and the first Christian Roman emperor, Constantine the Great. While modern history usually counts eleven emperors named Constantine, older works sometimes numbered Constantine Palaiologos differently. Some counted him as Constantine XIII. The modern number, XI, became common in 1836. There is some confusion because two different Roman emperors are called Constantine III. Also, an emperor known today as Constans II actually ruled under the name Constantine. And it's unclear if Constantine Laskaris was truly an emperor. If he was, Constantine Palaiologos would be Constantine XII.

If we count everyone officially recognized as a ruler named Constantine, including those who were only co-emperors but had the supreme title, there would be 18 emperors named Constantine. But historians usually don't number co-emperors. This is because their rule was mostly just a title. They didn't have independent power unless they later inherited the throne. If we count the Western Constantine III, Constans II, and Constantine Laskaris (who had supreme power, though Laskaris's case is debated), then Constantine Palaiologos would be Constantine XIV.

See also

In Spanish: Constantino XI Paleólogo para niños

In Spanish: Constantino XI Paleólogo para niños

- List of Byzantine emperors

- Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty

- Rise of the Ottoman Empire

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |