Fourth Crusade facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Fourth Crusade |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crusades | |||||||

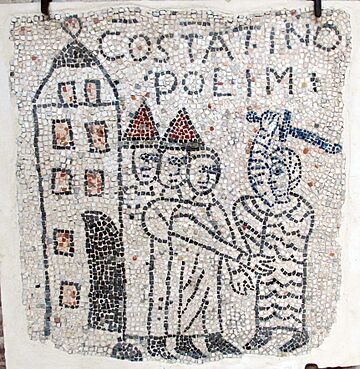

A 15th-century miniature depicting the conquest of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Kingdom of France

|

In Europe: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Al-Adil |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a big military journey by Western European Christians. It was called by Pope Innocent III. The main goal was to take back the city of Jerusalem from Muslim control. To do this, the plan was to first defeat the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid Sultanate.

However, things didn't go as planned. Because of money problems and political changes, the Crusader army ended up attacking the city of Zadar (Zara) in 1202. Then, in 1204, they attacked and looted Constantinople. This was the capital of the Byzantine Empire, which was a Christian city. This event led to the Byzantine Empire being split up by the Crusaders and their allies from Venice. This period is known as Frankokratia, or "Rule of the Franks."

The Republic of Venice agreed to build a large fleet to carry the Crusader army. But the Crusader leaders thought more soldiers would show up than actually did. The army that arrived couldn't pay the agreed price for the ships. So, the leader of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, suggested that the Crusaders help him attack the city of Zara. Zara had rebelled against Venice.

In November 1202, the Crusaders attacked and took Zara. This was the first time a Catholic Crusader army attacked a Catholic city. Pope Innocent III had told them not to attack other Christians. When the Pope found out, he temporarily removed the Crusaders from the Church.

In January 1203, on their way to Jerusalem, the Crusader leaders made a deal with a Byzantine prince named Alexios IV Angelos. He asked them to go to Constantinople and help him put his father, Isaac II Angelos, back on the throne. In return, Alexios promised to help them with their journey to Jerusalem. On June 23, 1203, the main Crusader army reached Constantinople. Some other Crusader groups continued towards the Holy Land.

After a battle in August 1203, Alexios was crowned co-emperor. But in January 1204, a rebellion removed him from power. This meant the Crusaders wouldn't get the money Alexios had promised. After Alexios was killed in February, the Crusaders decided to conquer Constantinople themselves. In April 1204, they captured the city and took its huge wealth. Only a few Crusaders went on to the Holy Land after this. Some important Crusaders disagreed with attacking Zara and Constantinople. They refused to join and left the Crusade.

After Constantinople was conquered, the Byzantine Empire broke into three smaller states. The Crusaders then created new Crusader states in the former Byzantine lands. These were called Frankokratia states. The most important was the Latin Empire of Constantinople. These new states quickly started fighting with the Byzantine successor states and the Bulgarian Empire. Eventually, one of the Byzantine states, the Empire of Nicaea, took Constantinople back in July 1261. This restored the Byzantine Empire.

The Fourth Crusade made the split between the Eastern Orthodox and Western Catholic Churches much worse. It also severely damaged the Byzantine Empire. The looting of Constantinople and the many deaths weakened the region. The empire lost control of much of its land. This made the restored Byzantine Empire smaller and weaker. It was then more vulnerable to attacks from the growing Ottoman Sultanate in later centuries. The Byzantine Empire finally fell to the Ottomans in 1453.

Contents

Why the Crusade Happened

Jerusalem and the Truce

In 1187, the Ayyubid Sultanate led by Saladin conquered most of the Christian Crusader states. Jerusalem was lost after a battle in 1187. This led to the start of the Third Crusade. The Crusader states were left with only three cities on the coast: Tyre, Tripoli, and Antioch.

The Third Crusade (1189–1193) aimed to get Jerusalem back. It managed to reclaim a lot of land and rebuilt the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Jerusalem itself wasn't taken back, but important coastal towns like Acre and Jaffa were. On September 2, 1192, a peace treaty was signed with Saladin. This ended the crusade and set a truce for over three years.

This crusade also increased tensions between Western Europe and the Byzantine Empire. During the Third Crusade, Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa almost attacked Constantinople. This was because the Byzantine Emperor, Isaac II Angelos, didn't give him safe passage. The Byzantines also thought Frederick was working with rebellious Serbian and Bulgarian groups. King Richard I Lionheart of England also took the Byzantine island of Cyprus. He gave it to Guy of Lusignan, a former king of Jerusalem.

Saladin died in 1193. His empire was then divided among his sons and brothers. The new ruler of Jerusalem, Henry II of Champagne, extended the truce with the Egyptian Sultan. In 1197, German Crusaders arrived and broke the peace. They attacked the territory of al-Adil I, who responded by attacking Jaffa. Jaffa was taken. However, the Germans did capture Beirut in the north.

Henry was replaced by Aimery of Cyprus. He signed a new truce with al-Adil in 1198. This truce kept things mostly the same. Jaffa stayed with the Ayyubids, but its defenses couldn't be rebuilt. Beirut stayed with the Crusaders. Before this truce ended in 1204, al-Adil had united Saladin's former empire. His lands almost completely surrounded the smaller Crusader states.

Constantinople's Situation

Constantinople was a huge and advanced city. It had been around for 874 years by the time of the Fourth Crusade. It was the largest city in the Christian world. It still had many ancient Roman buildings, baths, and aqueducts working. At its peak, about half a million people lived there. Strong triple walls, about 20 km (13 miles) long, protected the city.

Constantinople's location made it the capital of the eastern Roman Empire. It was also a major trading hub. Trade routes from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea, China, India, and Persia passed through it. This made it a rich target for new Western states, especially the Republic of Venice.

In 1195, the Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelos was removed from power by his brother. His brother, Alexios III Angelos, became the new emperor. Alexios III had his brother Isaac blinded, which was a common punishment for treason. Isaac had been a weak ruler. He had spent the empire's money and let the navy weaken. The new emperor, Alexios III, was no better. He spent even more money and neglected the empire's defenses and diplomacy. The navy's admiral even sold off equipment for his own profit.

Meeting in Venice

Pope Innocent III became Pope in 1198. His main goal was to start a new crusade. European kings mostly ignored his call. England and France were fighting each other. But a crusading army was finally formed in 1199. This happened at a tournament in Écry-sur-Aisne. Count Thibaut of Champagne was chosen as leader. He died in 1201 and was replaced by Boniface of Montferrat.

Boniface and other leaders sent people to Venice, Genoa, and other cities in 1200. They wanted to arrange transport to Egypt, which was their target. One of these envoys was the future historian Geoffrey of Villehardouin. Earlier crusades had traveled slowly by land across a difficult Anatolia. Attacking Egypt meant needing a large fleet. Genoa wasn't interested. But in March 1201, negotiations began with the leader of Venice, Enrico Dandolo.

Dandolo agreed to transport 33,500 Crusaders. This was a very ambitious number. Venice needed a full year to build many ships and train sailors. This also meant stopping their usual trading activities. The Crusader army was expected to have 4,500 knights, 9,000 squires, and 20,000 foot soldiers.

Most of the Crusader army that left Venice in October 1202 came from France. Other groups came from Flanders, Montferrat, and the Holy Roman Empire. The Venetian soldiers and sailors were led by Doge Enrico Dandolo. The plan was to sail by June 24, 1203, directly to Cairo, the Ayyubid capital. Pope Innocent approved this plan. He strictly forbade attacks on Christian states.

The Crusade Changes Course

Attack on Zara

Not all Crusaders sailed from Venice. Many chose other ports like Marseille and Genoa. By May 1202, most of the Crusader army was in Venice. But there were far fewer soldiers than expected: about 12,000 instead of 33,500. The Venetians had built enough ships for three times the army.

The Venetians, led by the old and blind Doge Dandolo, wouldn't let the Crusaders leave without full payment. The original price was 85,000 silver marks. The Crusaders could only pay 35,000 marks at first. Dandolo threatened to keep them there. So, another 14,000 marks were collected, which made the Crusaders very poor. This was bad for Venice too, as they had stopped their trade to prepare the fleet. Also, about 14,000 to 30,000 Venetians were needed to man the fleet, which strained their economy.

Dandolo suggested that the Crusaders pay their debt by attacking cities along the Adriatic coast. This would end with an attack on Zara in Dalmatia. Zara had been under Venice's economic control but rebelled in 1181. It had allied with King Emeric of Hungary. King Emeric was Catholic and had joined a crusade himself.

Many Crusaders were against attacking Zara. Some, like Simon de Montfort, refused to take part. They went home or sailed to the Holy Land on their own. The Pope's representative, Cardinal Peter of Capua, said it was necessary to save the crusade. But the Pope was worried and threatened to remove the Crusaders from the Church.

This letter from Pope Innocent III might not have reached the army in time. The army arrived at Zara on November 10–11, 1202. The citizens of Zara showed they were fellow Catholics by hanging banners with crosses. But the city still fell on November 24, 1202, after a short battle. There was a lot of looting. The Venetians and Crusaders even fought over the spoils. The leaders decided to stay in Zara for the winter. The Venetians destroyed Zara's defenses.

When Pope Innocent III heard about the attack, he sent a letter removing them from the Church. He ordered them to go to Jerusalem. But the Crusader leaders didn't tell their followers about this. The Pope later changed his mind for the non-Venetians. He thought they had been forced by the Venetians.

The Decision to Go to Constantinople

There was a lot of bad feeling between Venice and the Byzantine Empire. This was made worse by the memory of the Massacre of the Latins. According to one story, Doge Enrico Dandolo had been blinded by the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos in 1171. This might have made him personally angry at the Byzantines.

Meanwhile, Boniface of Montferrat had left the fleet before it sailed from Venice. He visited his cousin Philip of Swabia. It's debated why he went. He might have known Venice's plans and wanted to avoid being removed from the Church. Or he might have wanted to meet the Byzantine prince Alexios IV Angelos. Alexios was Philip's brother-in-law and the son of the recently removed Byzantine emperor Isaac II Angelos.

Alexios IV offered to pay the Crusaders' debt to Venice. He also offered 200,000 silver marks to the Crusaders. He promised 10,000 Byzantine soldiers for the Crusade. He would also provide 500 knights in the Holy Land and the Byzantine navy to transport the army to Egypt. Finally, he promised to put the Eastern Orthodox Church under the Pope's authority. This offer reached the Crusader leaders on January 1, 1203, while they were in Zara.

Doge Dandolo strongly supported the plan. He knew a lot about Byzantine politics. It's likely he knew Alexios's promises were false. He probably knew no Byzantine emperor could raise that much money or give the church to the Pope. Count Boniface agreed. Alexios IV then rejoined the fleet at Corfu. Most other Crusader leaders, encouraged by Dandolo, also accepted the plan.

However, some disagreed. Led by Renaud of Montmirail, they refused to attack Constantinople. They sailed directly to Syria. The remaining fleet of 60 war galleys, 100 horse transports, and 50 large troop transports sailed in late April 1203. This fleet had 10,000 Venetian oarsmen and marines. They also brought 300 siege engines. The Pope then said not to attack Christians unless they were stopping the Crusade. But he didn't fully condemn the plan.

Constantinople's Defenses

When the Fourth Crusade arrived at Constantinople on June 23, 1203, the city had about 500,000 people. It had a small army of 15,000 men, including 5,000 Varangians. It also had a fleet of 20 galleys. The city's army was usually small for political and financial reasons. In the past, reinforcements could be called from other areas. But this time, the Crusaders' sudden arrival put the defenders at a disadvantage.

The Crusaders' main goal was to put Alexios IV on the Byzantine throne. This was so they could get the money he promised. Conon of Bethune delivered this demand to the Byzantine Emperor Alexios III Angelos. Alexios III was the uncle of Alexios IV and had taken the throne from Alexios IV's father, Isaac II. The people of Constantinople didn't care much about the deposed emperor and his son. In their culture, one brother taking the throne from another wasn't seen as wrong.

First, the Crusaders attacked the suburbs of Chalcedon and Chrysopolis. They were pushed back. They then won a small cavalry battle, defeating 500 Byzantines with only 80 Frankish knights.

July 1203 Battle

To take the city, the Crusaders first had to cross the Bosphorus strait. About 200 ships carried the army across. Alexios III had lined up his army along the shore. But the Crusader knights charged straight from their ships, and the Byzantine army ran away. The Crusaders then attacked the Tower of Galata. This tower held the huge chain that blocked ships from entering the Golden Horn harbor. The Tower of Galata had mercenary soldiers. On July 6, the largest Crusader ship broke the chain.

While the Crusaders attacked the Tower of Galata, the defenders tried to fight back. They often lost many soldiers. Once, many defenders drowned trying to escape back to the tower. The tower was quickly taken. The Golden Horn was now open to the Crusaders. The Venetian fleet entered. The Crusaders sailed along Constantinople's walls with 10 galleys. They showed Alexios IV to the citizens. But the people on the walls made fun of the Crusaders. The Crusaders had been told the citizens would welcome Alexios as a hero.

On July 11, the Crusaders took positions near the Palace of Blachernae. Their first attacks were pushed back. But on July 17, the Venetians attacked the sea walls from the Golden Horn. They took a section of the wall with about 25 towers. The Varangian Guard, the emperor's elite soldiers, held off the Crusaders on the land wall. The Varangians moved to fight the Venetians. The Venetians retreated under fire. The fire destroyed about 120 acres of the city. About 20,000 people lost their homes.

Alexios III finally attacked. He led 17 divisions, much larger than the Crusaders. Alexios III's army of about 8,500 men faced the Crusaders' 3,500 men. But Alexios III lost his courage. The Byzantine army returned to the city without a fight. This retreat and the fire hurt morale. Alexios III then secretly left the city and fled. Imperial officials quickly removed him and restored Isaac II. This took away the Crusaders' reason to attack.

The Crusaders insisted they would only recognize Isaac II if his son, Alexios, was also made co-emperor. On August 1, Alexios was crowned as Alexios IV Angelos, co-emperor.

Alexios IV's Rule

Alexios IV soon realized his promises were hard to keep. Alexios III had fled with a lot of gold and jewels. This left the imperial treasury low on money. Alexios IV ordered valuable Roman icons to be destroyed and melted for their gold and silver. But even then, he could only raise 100,000 silver marks. To the Greeks, this was a shocking sign of desperation. The Byzantine historian Nicetas Choniates called it "the turning point towards the decline of the Roman state."

Forcing people to destroy their religious icons for foreign soldiers made Alexios IV very unpopular. Fearing for his life, Alexios IV asked the Crusaders to stay for another six months, until April 1204. Alexios IV then led 6,000 Crusader soldiers against his rival Alexios III.

While Alexios IV was away in August, riots broke out in Constantinople. Some Latin residents were killed. In return, armed Venetians and other Crusaders entered the city. They attacked a mosque, which was defended by Muslims and Byzantine Greeks. To cover their retreat, the Westerners started the "Great Fire." This fire burned from August 19 to 21. It destroyed a large part of Constantinople and left about 100,000 people homeless.

In January 1204, the blind and sick Isaac II died. Opposition to his son, Alexios IV, had grown. The Byzantine Senate elected a young noble, Nicolas Canabus, as emperor. But he refused and sought safety in a church.

A nobleman named Alexios V Doukas (nicknamed Mourtzouphlos) became the leader of the anti-Crusader group. He had led Byzantine forces against the Crusaders and was respected. He moved against Alexios IV, overthrew him, imprisoned him, and had him killed in early February. Doukas was then crowned Emperor Alexios V Doukas Mourtzouphlos. He immediately strengthened the city's defenses and called for more soldiers.

War Against Alexios V

The Crusaders and Venetians were angry about the murder of Alexios IV. They demanded that Alexios V honor the promises Alexios IV had made. When the new emperor refused, the Crusaders attacked the city again. On April 8, Alexios V's army fought strongly. They threw large rocks at the enemy siege machines, breaking many of them. Bad weather also hindered the Crusaders. A strong wind blew from the shore, stopping most ships from getting close to the walls. Only five towers were attacked, and none were taken. By afternoon, the attack had failed.

The Latin church leaders discussed the situation. They decided to tell the army that the failure was not God's judgment. They said the campaign was right and would succeed with faith. They explained that God was testing the Crusaders. They argued that attacking Constantinople was right because the Greeks were "traitors and murderers" for killing Alexios IV. They claimed the Greeks were "worse than the Jews" and said God and the Pope supported their actions.

Pope Innocent III had again told them not to attack. But the clergy hid his letter. The Crusaders prepared for another attack, while the Venetians attacked from the sea. Alexios V's army stayed to fight. But when the unpaid Varangians left the city, Alexios V himself fled during the night. An attempt was made to find a new Byzantine emperor, but the situation was too chaotic.

On April 12, 1204, the weather helped the Crusaders. A strong northern wind pushed the Venetian ships close to the walls. After a short fight, about seventy Crusaders entered the city. Some made holes in the walls for knights to crawl through. The Venetians also climbed the walls from the sea. The Anglo-Saxon "axe bearers" had been good defenders. But they tried to get higher pay from the Byzantines, then left or surrendered. The Crusaders captured the Blachernae section of the city. They used it as a base to attack the rest. While trying to defend themselves with fire, they accidentally burned even more of the city. This second fire left 15,000 people homeless. The Crusaders completely took the city on April 13.

Looting of Constantinople

The Crusaders looted Constantinople for three days. Many ancient Greek and Roman artworks were stolen or destroyed. Many civilians were killed, and their property was taken. Even though they faced being removed from the Church, the Crusaders destroyed and looted churches and monasteries. It's said that about 900,000 silver marks were stolen from Constantinople.

The Venetians received 150,000 silver marks they were owed. The Crusaders received 50,000 silver marks. Another 100,000 silver marks were split between them. But many Crusader knights secretly kept back 500,000 silver marks. Eyewitnesses like Niketas Choniates and Geoffrey of Villehardouin all said the Crusaders were very greedy.

Historian Speros Vryonis described the looting:

The Latin soldiers looted the greatest city in Europe in an unspeakable way. For three days they murdered, [...] looted and destroyed so much that even the ancient Vandals and Goths would have found it unbelievable. [...] The defeat of Byzantium, which was already in decline, made its political situation worse. This made the Byzantines easy targets for the Turks later. The Fourth Crusade and the Crusades in general ended up helping Islam, which was the opposite of their original goal.

When Pope Innocent III heard about what his pilgrims had done, he was filled with shame and anger. He strongly criticized them.

The Holy Land

The main army that sailed from Venice to Constantinople had many soldiers leave. They wanted to fulfill their vows by going directly to the Holy Land. Most of them sailed from ports in southern Italy to Acre. According to Villehardouin, most of those who started the Fourth Crusade went to the Holy Land. Only a few participated in the attack on Constantinople. However, modern historians think Villehardouin might have exaggerated this.

Historians now believe a good number, but not a majority, went to the Holy Land. For example, about a tenth of the knights from Flanders who joined the crusade went to the Holy Land. More than half of those from Île-de-France did. In total, about 300 knights and their groups from northern France made it to the Holy Land. There were also soldiers from other areas who left the main army.

A large sum of money collected by the preacher Fulk of Neuilly did reach the Holy Land. It was used to repair walls and defenses damaged by an earthquake in May 1202. A second wall was even added at Acre.

From Italy to Acre

Some Crusaders, instead of going to Venice, went south in Italy in 1202. They planned to go directly to the Holy Land from southern Italian ports. Several hundred knights and foot soldiers reached the Holy Land this way. The force was so small that King Aimery of Jerusalem refused to break his truce with the Ayyubids. He wouldn't let them go to war.

Eighty Crusaders decided to go to the Principality of Antioch, which had no truce. They were ambushed on the road, and all but their leader, Renard, were killed or captured. Renard stayed captive for thirty years.

After the crusade was diverted to Zara, more Crusaders left the main army. Some found other ways to go to the Holy Land. The historian's nephew, Geoffrey I of Villehardouin, was one of them. Others, like Stephen of the Perche, sailed directly to the Holy Land from southern Italy in March 1203.

After the siege of Zara, about 2,000 men left the main army. Most were poorer Crusaders. Two ships carrying them sank. An official group was sent to the Holy Land from Zara. They were supposed to return to the main army, but they stayed in the Holy Land until after Constantinople fell.

In the winter of 1203–1204, Simon V of Montfort led a large group of Crusaders who were disgusted with the attack on Zara. They were also against going to Constantinople. They marched from Zara back to Italy. Then they sailed from Italy to Palestine.

Flemish Fleet

For unknown reasons, Baldwin of Flanders split his forces. He led half to Venice and sent the other half by sea. The Flemish fleet left Flanders in the summer of 1202. It sailed into the Mediterranean. According to one writer, it attacked and captured a Muslim city in Africa. The fleet then went to Marseille, where it stayed for the winter of 1202–1203. Many French Crusaders joined the fleet there.

The pilots from Marseille were very experienced. They could sail to Acre in fifteen days in the summer. They had enough ships to transport a large army. It was also a cheaper port for the French.

Baldwin sent orders for his fleet in Marseille to sail at the end of March 1203. They were to meet the Venetian fleet off Methoni. His messengers must have also brought news of the decision to go to Constantinople first. So, the Flemish leaders might have ignored the meeting and sailed directly to Acre. They probably arrived there before April 25, 1203. Part of the fleet stopped at Cyprus. Thierry of Flanders claimed the island for his wife. But the king of Cyprus ordered them to leave. So they went to the Kingdom of Armenia.

The Flemish Crusaders in Acre faced the same problem as Renard of Dampierre. King Aimery didn't want to break his truce for such a small army. So the Crusaders split up. Some joined the army of Antioch, and others joined Tripoli. Some even ended up fighting their former comrades. By November 5, 1203, the truce was broken. Muslims seized two Christian ships, and Christians seized six Muslim ships in return. The Flemish Crusaders returned to the Kingdom of Jerusalem to fight.

On November 8, two Crusaders were sent to the main army, which was attacking Constantinople. They urged the army to continue to the Holy Land now that the truce was broken. The envoys arrived on January 1, 1204. But the army was in heavy fighting, and nothing came of their request.

The East–West Split

Pope Innocent III was very upset about the terrible things the Crusaders had done. He spoke against them, saying:

How will the Greek Church, no matter how much it suffers, return to unity with the Pope? It has seen only destruction and evil from the Latins. Now, with good reason, it hates the Latins more than dogs. Those who were supposed to seek Jesus Christ's goals, not their own, made their swords drip with Christian blood. They spared no religion, age, or gender. [...] They not only broke into the imperial treasury and stole from princes and common people, but they also took treasures from churches. Even worse, they took the churches' own property. They ripped silver plates from altars and cut them into pieces among themselves. They violated holy places and carried off crosses and holy items.

Splitting the Byzantine Empire

After the conquest, a treaty divided the Byzantine Empire among Venice and the Crusader leaders. The Latin Empire of Constantinople was created. Boniface was not chosen as the new emperor. The Venetians thought he had too many connections to the old empire. They also thought he would favor Genoa over Venice. Instead, they put Baldwin of Flanders on the throne.

Boniface went on to create the Kingdom of Thessalonica. This was a state that served the new Latin Empire. The Venetians also created the Duchy of the Archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Meanwhile, Byzantine refugees formed their own smaller states. The most important were the Empire of Nicaea, the Empire of Trebizond, and the Despotate of Epirus. This division was known as the Partitio terrarum imperii Romaniae.

Venetian Lands

The Republic of Venice gained several lands in Greece. Some of these stayed Venetian until 1797.

- Crete (1211–1669): A very important possession. Venice held it despite many Greek revolts until the Ottomans captured it.

- Corfu (1207–1214 and 1386–1797): Venice took it after the Fourth Crusade. It was later retaken by others but Venice got it back in 1386.

- Lefkas (1684–1797): Came under Ottoman rule, then conquered by Venetians in 1684.

- Zakynthos (1479–1797): Fell to Venice in 1479.

- Cephalonia and Ithaca (1500–1797): Conquered by Venetians in 1500.

- Tinos and Mykonos: Given to Venice in 1390.

- Various coastal forts in Greece, like Modon and Koroni.

Genoese Lands

The Republic of Genoa tried to take Corfu and Crete but Venice stopped them. In the 1300s, as the Byzantine Empire weakened, Genoese nobles set up their own areas in the northeastern Aegean.

- The Gattilusi family ruled islands like Lesbos (1355–1462) and Lemnos.

- The Lordship of Chios with the port of Phocaea.

Crusader Lands

The Latin Empire and the Fourth Crusade leaders created their own kingdoms in the Byzantine Empire.

- Duchy of Philippopolis (1204 – after 1230): A part of the Latin Empire in northern Thrace, later taken by the Bulgarians.

- Lemnos: An island ruled by the Venetian Navigajoso family until 1278.

- The Kingdom of Thessalonica (1205–1224): This kingdom was given to Boniface of Montferrat. He expanded Latin control south into Greece. It was often at war with the Second Bulgarian Empire. It was eventually conquered by the Despotate of Epirus.

- The County of Salona (1205–1410): Created as a state serving the Kingdom of Thessalonica. It was later sold to the Knights Hospitaller.

- The Marquisate of Bodonitsa (1204–1414): Also created as a state serving the Kingdom of Thessalonica.

- The Principality of Achaea (1205–1432): This state in the Peloponnese became the strongest Crusader state. It lasted even after the Latin Empire fell.

- The Duchy of Athens (1205–1458): With capitals at Thebes and Athens. It was later conquered by the Catalan Company.

- The Lordship of Argos and Nauplia (1212–1388): Given to the Duke of Athens. Later sold to Venice.

- The Duchy of the Archipelago or of Naxos (1207–1579): Founded by the Sanudo family. It included most of the Cyclades islands. It became an Ottoman vassal and was later fully taken by the Ottoman Empire.

- The Triarchy of Negroponte (1205–1470): This island was divided into three parts. Venice gained control of the whole island by 1390.

- The County palatine of Cephalonia and Zakynthos (1185–1479): Included the Ionian Islands.

- Rhodes: Became the headquarters of the Knights Hospitaller in 1310. They controlled the island until the Ottomans took it in 1522.

Frankish Rule in Greece

The Frankokratia (meaning "rule of the Franks") or Latinokratia ("rule of the Latins") was a period in Greek history after the Fourth Crusade (1204). During this time, many French and Italian states were set up in the lands of the broken Byzantine Empire. The terms "Franks" and "Latins" were used by the Eastern Orthodox Greeks for the Western Europeans.

The length of the Frankokratia period varied. The Frankish states often broke apart or changed hands. The Greek successor states also took back many areas. Except for the Ionian Islands and some Venetian forts, the Frankokratia ended in most Greek lands with the Ottoman conquest. This happened mainly from the 1300s to the 1600s. This period is known as "Tourkokratia" ("rule of the Turks").

During the half-century after the Fourth Crusade, the unstable Latin Empire used up much of Europe's crusading energy. The Fourth Crusade left a deep feeling of betrayal among Greek Christians. The events of 1204 made the split between the Eastern and Western Churches permanent.

During the Frankokratia, the Latin Empire faced many enemies. The Crusaders couldn't take over the entire Byzantine Empire. They faced several smaller Eastern Roman states. These states saw themselves as the true successors to the emperor. The three most important were the Despotate of Epirus, the Empire of Nicaea, and the Empire of Trebizond. The Crusaders were also threatened by the Christian Second Bulgarian Empire and the Muslim Sultanate of Rûm. The Crusaders simply didn't have enough soldiers to hold their new lands permanently.

The broken Eastern Roman states fought against the Crusaders, Bulgarians, Turks, and each other. The unstable Latin Empire used up much of Europe's crusading energy. The legacy of the Fourth Crusade and Frankokratia was a deep sense of betrayal felt by the Greek Christians. The events of 1204 made the split between the Eastern and Western Churches permanent.

During Frankokratia, the Latin-French areas in Greece helped connect with Western Europe. They also encouraged the study of Greek. There was also French cultural influence, like a collection of laws called the Assises de Romanie. The Chronicle of Morea was written in French and Greek. You can still see impressive Crusader castles and Gothic churches in Greece. However, the Latin Empire was always weak.

Constantinople was taken back by the Nicaeans in 1261. This led to the restoration of a smaller Byzantine Empire. Trade with Venice restarted. But the Nicaeans gave their Genoese allies control of Galata, a fortress across the Golden Horn.

The Fourth Crusade had other big impacts. During Frankokratia, Byzantine lands without stable governments were lost forever to the Seljuks in Anatolia. Southern Greece and the Greek islands mostly stayed under the rule of Crusaders, Italian nobles, and Venice. Even the Greek Despotate of Epirus was ruled by an Italian noble family. Most of these Crusader kingdoms would later become part of the Ottoman Empire, not the restored Byzantine state. The Byzantine Empire's treasury was emptied, mostly by the Crusaders. All these factors sped up the final fall of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. This final fall began a new era for Greece, known as Tourkokratia, or "the Rule of the Turks."

Images for kids

-

The Frankish tower on the Acropolis of Athens, demolished in 1874

-

Rhodes (city), around 1490

-

Church of Virgin, Rhodes (city)

Venetian possessions (till 1797):

-

Stato da Màr of the Republic of Venice

-

Venetian map of Negroponte (Chalkis)

-

Palamidi, Nafplion

-

Rocca a Mare fortress in Heraklion

-

The Morosini fountain, Lions Square, Heraklion

See also

In Spanish: Cuarta cruzada para niños

In Spanish: Cuarta cruzada para niños

- Latin Church in the Middle East

- Third Crusade

- Bulgarian-Latin Wars

- Laskaris

- Timeline of Orthodoxy in Greece (1204–1453)

- Succession of the Roman Empire

- Second Bulgarian Empire

- Medieval Bulgarian Army

- Principality of Arbanon