Second Bulgarian Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bulgarian Empire

ц︢рьство блъгарское

българско царство |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1185–1396 | |||||||||||||||||

|

Top: Flag according to Dulcert's portolan (c. 1325)

Bottom: Flag according to Soler's portolan (c. 1380) |

|||||||||||||||||

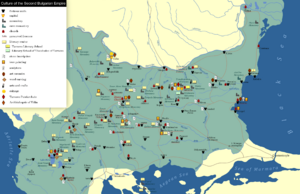

Second Bulgarian Empire under Ivan Asen II

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tarnovo (1185–1393) Nikopol (1393–1395) Vidin (1356/1371–1396 as capital of the Tsardom of Vidin) |

||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Bulgarian, Common Romanian, Balkan Latin, Medieval Greek, Cuman | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Bulgarian Orthodoxy (official, 1204–1235 in the union with Rome) Bogomilism (banned) |

||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Bulgarian | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Tsar (Emperor) | |||||||||||||||||

|

• 1185–1190

|

Peter IV (first) | ||||||||||||||||

|

• 1397–1422

|

Constantine II of Bulgaria (last) | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||

| 1185 | |||||||||||||||||

|

• Fall under Ottoman rule

|

1396 | ||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| 1230 | 293,000 km2 (113,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

The Second Bulgarian Empire was a powerful medieval state in the Balkans. It existed from 1185 to 1396. This empire was a successor to the First Bulgarian Empire. It became very strong under leaders like Kaloyan and Ivan Asen II. However, it was slowly taken over by the Ottomans in the late 1300s.

For a long time, until 1256, the Second Bulgarian Empire was the strongest power in the Balkans. It won many important battles against the Byzantine Empire. In 1205, Emperor Kaloyan defeated the new Latin Empire at the Battle of Adrianople. His nephew, Ivan Asen II, defeated the Despotate of Epiros. This made Bulgaria a major force in the region again. During his rule, Bulgaria stretched from the Adriatic Sea to the Black Sea. Its economy also grew a lot.

Later, in the late 1200s, the Empire started to weaken. It faced constant attacks from Mongols, Byzantines, Hungarians, and Serbs. There were also many problems and revolts inside the country. By the 1300s, Bulgaria was split into three parts just before the Ottoman invasion.

Even with strong Byzantine influences, Bulgarian artists and builders created their own unique style. The 1300s were known as the Second Golden Age of Bulgarian culture. During this time, writing, art, and architecture thrived. The capital city, Tarnovo, was seen as a "New Constantinople." It became the main cultural center for Bulgarians and the Eastern Orthodox Church. After the Ottomans took over, many Bulgarian religious leaders and scholars moved to other places. They went to Serbia, Wallachia, Moldavia, and Russian principalities. There, they shared Bulgarian culture, books, and hesychastic ideas.

Contents

What Was It Called?

People at the time usually called the empire "Bulgaria." The state itself used this name. During Kaloyan's rule, it was sometimes known as the state of both Bulgarians and Vlachs. Important foreign leaders, like Pope Innocent III and Latin Emperor Henry, called it "Bulgaria" or the "Bulgarian Empire" in their official letters.

Today, historians call it the "Second Bulgarian Empire." This helps tell it apart from the First Bulgarian Empire. Sometimes, for the period before the mid-1200s, it's also called the "Empire of Vlachs and Bulgarians."

How the Empire Began

In 1018, the Byzantine emperor Basil II conquered the First Bulgarian Empire. He was careful in how he ruled. The tax system, laws, and power of the local nobles stayed the same at first. The Bulgarian Orthodox Church became part of the Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople. It was lowered to an archbishopric but kept some independence.

As the Byzantine Empire weakened, new taxes and attacks from groups like the Pechenegs made people unhappy. This led to several big uprisings in the 1000s and 1100s. The first rebellions started in what is now Macedonia. These were put down by the Byzantines with great effort.

History of the Second Bulgarian Empire

The Start of the Rebellion

The rule of the last Byzantine emperor, Andronikos I, made life hard for Bulgarian farmers and nobles. His successor, Isaac II Angelos, added a new tax to pay for his wedding. In 1185, two noble brothers from Tarnovo, Theodore and Asen, asked the emperor for land and a place in the army. Isaac II refused and even slapped Asen.

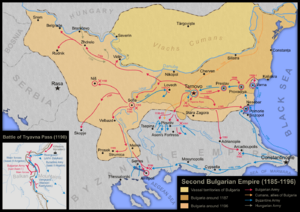

When they returned to Tarnovo, the brothers built a church for Saint Demetrius of Salonica. They showed the people a famous picture of the saint. They claimed he had left Thessalonica to help the Bulgarians. This encouraged people to rebel against the Byzantines. Theodore, the older brother, was crowned Emperor Peter IV. Almost all of Bulgaria north of the Balkan Mountains joined the rebels. They also got help from the Cumans, a Turkic tribe. The Cumans became a key part of the Bulgarian army.

Peter IV tried to take the old capital of Preslav but failed. He declared Tarnovo the new capital of Bulgaria. The Bulgarians then attacked northern Thrace while the Byzantine army was fighting the Normans. The Byzantines tried to crush the rebellion in mid-1186. The Bulgarians had blocked the mountain passes, but the Byzantines found a way through. The rebels avoided a direct fight. Peter IV pretended he would surrender, while Asen went north to gather more soldiers. The Byzantine emperor burned Bulgarian crops and went back to Constantinople.

Soon after, Asen returned with Cuman help. He declared he would fight until all Bulgarian lands were free. The Byzantines sent new armies, but the Bulgarians kept raiding Thrace. In 1190, Isaac II led another campaign against Bulgaria. It ended in a huge defeat at the Tryavna Pass. The emperor barely escaped, and the Bulgarians captured his treasury. After this win, Asen was crowned emperor and became Ivan Asen I. Peter IV willingly stepped aside for his more active brother.

Over the next four years, the war moved south of the Balkan mountains. Ivan Asen's quick attacks helped him take important cities like Sofia and Niš. In 1194, the Byzantines were defeated again at the Battle of Arcadiopolis. Ivan Asen demanded all Bulgarian lands back, and the war continued. In 1196, the Byzantine army lost again at Serres. When he returned to Tarnovo, Ivan Asen was killed by his cousin Ivanko. Peter IV was murdered less than a year later.

The Empire Grows Stronger

Kaloyan, the youngest brother of Asen and Peter IV, took the throne. He was a strong ruler who wanted Bulgaria to be recognized by other countries. He also wanted revenge on the Byzantines for blinding 14,000 of Emperor Samuel's soldiers. Kaloyan called himself "Roman-slayer," like Basil II was called "Bulgar-slayer."

Kaloyan quickly made peace with his brother's killer, Ivanko. In 1201, Kaloyan captured Varna, the last Byzantine stronghold in Moesia. He ordered all Byzantine soldiers to be thrown into the moat. He then made peace with the Byzantines, securing Bulgaria's new lands. While Bulgaria was busy in the south, the Hungarian king Andrew II and his Serbian ally took some northern lands. But Kaloyan defeated the Hungarians and Serbs, taking back his territory.

Kaloyan knew the Byzantines would not accept his title as emperor. So, he started talking with Pope Innocent III. He based his claims on the earlier Bulgarian emperors. The Pope agreed to recognize Kaloyan as king if the Bulgarian Church joined Rome. After long talks, Kaloyan was crowned king in late 1204. The Bulgarian Archbishop Basil was named Primate. Kaloyan, however, still saw himself as emperor and Basil as Patriarch. The Pope eventually accepted this. The union between Bulgaria and Rome was mostly on paper; Bulgarians kept their Orthodox traditions.

A few months before Kaloyan's crowning, leaders of the Fourth Crusade attacked the Byzantine Empire. They captured Constantinople and created the Latin Empire. The Bulgarians tried to be friends with the Latins, but the Latins claimed Bulgarian lands. Kaloyan and the Byzantine nobles in Thrace formed an alliance. On April 14, 1205, the Bulgarians defeated the Crusaders at Adrianople. The Latin emperor Baldwin I was captured. This battle greatly weakened the new Latin Empire.

After this victory, the Bulgarians took back most of Thrace. However, the Byzantine nobles then plotted against Kaloyan. Kaloyan reacted harshly against the Byzantines in Thrace. The war against the Latins continued. In 1206, the Bulgarians won at the battle of Rusion and took more towns. The next year, the King of Salonica was killed in battle. But Kaloyan was murdered before he could attack Salonica.

Kaloyan's cousin, Boril, took the throne. He tried to follow Kaloyan's plans but was not as skilled. His army lost to the Latins at the Battle of Philippopolis. Boril struggled to keep the empire together. His brother took over much of Macedonia. Boril also had to give up some land to Hungary to get help with a rebellion.

Ivan Asen II, son of Ivan Asen I, overthrew Boril in 1218. Ivan Asen II had been living in exile. After becoming emperor, he married the daughter of the Hungarian king and got back the cities of Belgrade and Braničevo. He then made an alliance with Theodore Komnenos, the ruler of the powerful Despotate of Epirus. Theodore conquered Salonica, making the Latin Empire much smaller.

By 1228, the Latins were in trouble. They talked with Bulgaria, offering to marry their young emperor to Ivan Asen II's daughter. This would have made the Bulgarian emperor a regent in Constantinople. But the Latins instead offered the regency to a French nobleman. In 1230, Theodore Komnenos, worried about Bulgaria, invaded with a huge army. Ivan Asen II quickly gathered a small force. He used the peace treaty with Theodore's oath on his spear as a banner. He won a major victory in the Battle of Klokotnitsa. Theodore Komnenos and his court were captured. Ivan Asen II let the ordinary soldiers go. All cities from Adrianople to Durazzo on the Adriatic Sea surrendered to him.

In 1231, Ivan Asen II allied with the Nicaean Empire against the Latins. After the Nicaeans recognized the Bulgarian Patriarchate in 1235, Ivan Asen II ended his union with the Pope. The joint attack on the Latins was successful, but they could not capture Constantinople. After the French nobleman died, Ivan Asen II decided to stop working with Nicaea. He thought that if they won, Constantinople would become the center of a restored Byzantine Empire under Nicaean rule. Ivan Asen II stayed peaceful with his southern neighbors until his death. In 1241, he defeated part of the Mongol army returning from attacking Poland and Hungary.

The Empire Weakens

Ivan Asen II's young son, Kaliman I, took over. Even though they had won against the Mongols, the new emperor's regents decided to pay tribute to them to avoid more attacks. Without a strong ruler and with growing fights among the nobles, Bulgaria quickly declined. Nicaea, which avoided Mongol raids, grew stronger in the Balkans. After Kaliman I died in 1246, several short-reigned rulers followed.

The Nicaean army took over large areas in southern Thrace, the Rhodopes, and Macedonia with little resistance. The Hungarians also took advantage of Bulgaria's weakness, occupying Belgrade and Braničevo. Bulgaria tried to fight back in 1253, regaining some land. But Michael II Asen's indecisiveness allowed the Nicaeans to take back most of their lost territory. In 1255, Bulgarians quickly regained Macedonia, as its people preferred Tarnovo's rule. But all gains were lost in 1256 due to a betrayal. This led to civil war until Constantine Tikh became emperor in 1257.

The new emperor faced many threats. The Latins attacked in 1257. More seriously, the Hungarians supported a rival emperor in Vidin. In 1260, Constantine Tikh took Vidin back. But a Hungarian counterattack forced the Bulgarians to retreat. The Byzantine Empire, now restored under Michael VIII Palaiologos, also made Bulgaria's situation worse. A big Byzantine invasion in 1263 led to the loss of coastal towns and cities in Thrace. Constantine Tikh tried to ally with the Mongols, but they just raided Thrace and left. The emperor became crippled after a hunting accident and was influenced by his wife, who caused more divisions among the nobles.

Constant Mongol raids, money problems, and the emperor's illness led to a huge uprising in 1277. The rebel army, led by a swineherd named Ivaylo, defeated the Mongols twice. This made Ivaylo very popular. Ivaylo then defeated the regular army and killed Emperor Constantine Tikh. He claimed the emperor did nothing to defend his honor.

The Byzantine emperor Michael VIII sent an army with a Bulgarian pretender, Ivan Asen III. But the rebels reached Tarnovo first. Constantine Tikh's widow married Ivaylo, and he was declared emperor. After the Byzantines failed, Michael VIII turned to the Mongols. They invaded and defeated Ivaylo's army, forcing him to hide. Ivaylo was then betrayed by the Bulgarian nobles, who let Ivan Asen III into Tarnovo. Ivaylo fought back, defeating two Byzantine armies. But his support weakened, and the Mongols were still a threat. Ivaylo sought refuge with the Mongols, who killed him. The nobles chose George I Terter as emperor. His rule brought more Mongol influence and loss of land. This period of trouble continued until 1300.

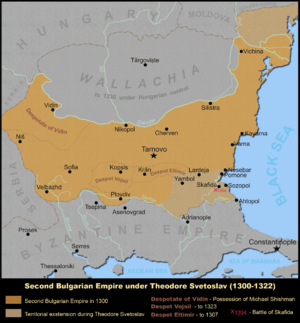

A Time of Stability

In 1300, Theodore Svetoslav, George I's oldest son, took advantage of a civil war among the Mongols. He overthrew a Mongol ruler and ended Mongol interference in Bulgaria. He also secured southern Bessarabia for Bulgaria. The new emperor started to rebuild the country's economy. He brought many independent nobles under control and punished those who helped the Mongols.

The Byzantines tried to cause trouble by supporting other rulers, but Theodore Svetoslav's uncle defeated them. Between 1303 and 1304, the Bulgarians took back many towns in north-eastern Thrace. The Byzantines were defeated in the battle of Skafida. They were forced to make peace in 1307, accepting Bulgaria's gains. Theodore Svetoslav spent the rest of his rule in peace. He had good relations with Serbia. These years of peace brought economic growth and boosted trade. Bulgaria became a major exporter of farm products, especially wheat.

In the early 1320s, problems grew between Bulgaria and the Byzantines. The Byzantines were in a civil war, and the new Bulgarian emperor George II Terter took Philippopolis. After George II died unexpectedly in 1322, the Byzantines recaptured the city. The next year, Michael Shishman was elected emperor. He immediately fought the Byzantine emperor and got back the lost lands. In late 1324, the two rulers signed a peace treaty. Michael Shishman divorced his Serbian wife, which worsened relations with Serbia. This change was due to Serbia's growing power in Macedonia.

Bulgaria and the Byzantines agreed to attack Serbia together. Michael Shishman gathered 15,000 troops and invaded Serbia. He fought the Serbian king Stephen Dečanski near Velbazhd. Both leaders expected more troops and agreed to a one-day truce. But when the Serbian king's son arrived, the Serbs broke the truce. The Bulgarians were defeated in the Battle of Velbazhd, and their emperor died. The Serbs did not invade Bulgaria, and peace was made. Bulgaria did not lose land but could not stop Serbia's growth in Macedonia.

After the defeat at Velbazhd, the Byzantines attacked Bulgaria. They took several towns in northern Thrace. Their success ended in 1332 when the new Bulgarian emperor Ivan Alexander defeated them at the battle of Rusokastro. He got back the captured lands. In 1344, the Bulgarians joined a Byzantine civil war, taking nine towns. This was the last major land gain for medieval Bulgaria. But it also led to the first attacks on Bulgarian land by the Ottoman Turks, who were allies of the other side in the civil war.

The Empire Falls

Ivan Alexander tried to fight off the Ottomans in the late 1340s and early 1350s. But he lost two battles. His oldest son and heir may have been killed. The emperor's relationship with his other son, Ivan Sratsimir, who ruled Vidin, got worse. This happened after Ivan Alexander divorced his wife to marry a Jewish woman in 1349. When their child was named heir, Ivan Sratsimir declared his independence.

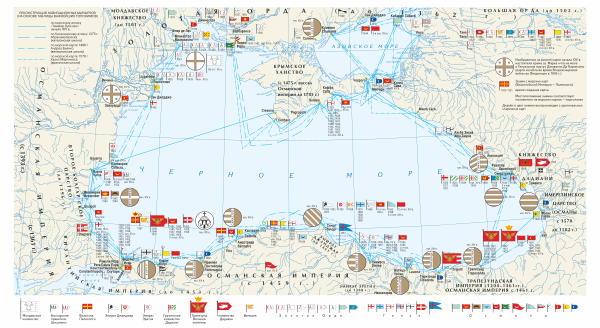

In 1366, Ivan Alexander refused to let the Byzantine emperor pass through. So, troops from the Savoyard crusade attacked the Bulgarian Black Sea coast. They took several towns, causing many deaths. The Bulgarians eventually let the Byzantine emperor pass, but the lost towns went to the Byzantines. In the north-west, the Hungarians attacked and took Vidin in 1365. Ivan Alexander got his province back four years later, with help from his allies.

When Ivan Alexander died in 1371, the country was divided. Ivan Shishman ruled in Tarnovo, Ivan Sratsimir in Vidin, and another noble in Karvuna. A German traveler in the 1300s described these lands as three parts of Bulgaria.

On September 26, 1371, the Ottomans defeated a large Christian army. They immediately turned on Bulgaria and conquered northern Thrace and other areas. This limited Ivan Shishman's power to lands north of the Balkan mountains. The Bulgarian ruler was forced to become an Ottoman vassal. In return, he got back some towns and had ten years of uneasy peace.

Ottoman attacks started again in the early 1380s, leading to the fall of Sofia. Ivan Shishman also fought Wallachia. He had bad relations with his brother Ivan Sratsimir, who had broken ties with Tarnovo. The two brothers did not work together against the Ottoman invasion. Ivan Shishman broke his promise to help the Ottomans. Instead, he joined Christian alliances, which led to huge Ottoman invasions in 1388 and 1393.

Despite strong resistance, the Ottomans took many important towns in 1388. Five years later, they captured Tarnovo after a three-month siege. Ivan Shishman died in 1395 when the Ottomans took his last fortress. In 1396, Ivan Sratsimir joined a Crusade, but the Christian army was defeated. The Ottomans then marched on Vidin and took it. This ended the medieval Bulgarian state. Resistance continued under Constantine and Fruzhin until 1422.

How the Empire Was Run

The Second Bulgarian Empire was a hereditary monarchy. This means the ruler's children inherited the throne. The ruler was called a Tsar, which is the Bulgarian word for Emperor. This title came from the First Bulgarian Empire. Bulgarian monarchs called themselves "Emperor and Autocrat of all Bulgarians." In the 1300s, "all Bulgarians" was added. This showed that the emperor in Tarnovo was the leader of all Bulgarian people, even those outside the country's borders.

The Emperor had total power over everything, both worldly and religious. The emperor's personal skills were very important for the country's success. If the monarch was a child, a group of regents, including the empress mother and the Patriarch, ran the government. As the country became more divided in the 1300s, it became common for the emperor's sons to get imperial titles while their father was still alive. They were called co-rulers or junior emperors.

The way Bulgaria was run was very much like the Byzantine system. Many titles for nobles, court officials, and administrators were taken directly from Byzantine Greek or translated into Bulgarian. The Bolyar Council included important nobles and the Patriarch. They discussed important issues like wars, alliances, and peace treaties. The highest officials were like a prime minister and a finance minister. High court titles were given to the Emperor's relatives but didn't always have specific jobs.

Tarnovo was the capital and was directly controlled by the emperor. Bulgaria was divided into provinces, which changed in number as the country's size changed. These provinces were usually named after their main city. Governors were called "duke" or "kefalia" and were chosen by the emperor. Provinces were further divided into smaller areas. During Ivan Asen II's rule (1218–41), provinces included Belgrade, Adrianople, Skopje, and Albania.

Bulgarian society had three main groups: clergy, nobles, and peasants. The nobles included the bolyars, who were like older Bulgarian nobles. They also included judges and the army. The bolyars were split into greater and lesser bolyars. The greater bolyars owned huge lands, sometimes with many villages. They held high government and military jobs. Peasants were the largest group. They worked for the central government or for local feudal lords. Over time, more peasants worked for feudal lords. The main types of peasants were paritsi and otrotsi. Both could own land, but only paritsi could pass it down to their children.

The Bulgarian Army

The emperor was the supreme commander of the army. The second-in-command was the "great voivoda." Army groups were led by a "voivoda." Another official was in charge of defending certain areas and recruiting soldiers. In the late 1100s, the army had 40,000 soldiers. By the early 1200s, Bulgaria could gather around 100,000 men. However, by the late 1200s, the army shrank to fewer than 10,000 men. Its strength grew again in the early 1300s, with 11,000–15,000 troops in the 1330s. The army had good siege equipment, like battering rams and catapults.

The Bulgarian army used different military tactics. They used the soldiers' experience and the local land features. The Balkan mountains were very important for defending the country. During wartime, Bulgarians would send light cavalry to destroy enemy lands. They would loot villages, burn crops, and take people and animals. The Bulgarian army was very fast. For example, before the Battle of Klokotnitsa, they covered three times the distance of the enemy army in four days.

Bulgaria had many fortresses to protect the country. The capital, Tarnovo, was in the center. There were lines of fortresses along the Danube river to the north. To the south, there were three lines of defense in the mountains. To the west, a line ran along the South Morava river valley.

Foreign and mercenary soldiers became a key part of the Bulgarian army. From the start of the rebellion, the fast Cuman cavalry was used effectively against the Byzantines and Crusaders. Cuman leaders even became part of the Bulgarian nobility. In the 1300s, the Bulgarian army used more foreign mercenaries, including Western knights, Mongols, and Wallachians. Both Michael III Shishman and Ivan Alexander had 3,000 Mongol cavalry in their armies. In the 1350s, Emperor Ivan Alexander even hired Ottoman groups.

Economy and Trade

The economy of the Second Bulgarian Empire relied on farming, mining, traditional crafts, and trade. Farming and raising animals were the main parts of the economy from the 1100s to the 1300s. Areas like Moesia and Dobrudzha were known for their rich grain harvests, including good quality wheat. Growing vegetables, fruits, and grapes became more important from the early 1200s. Large forests and pastures were good for raising livestock, especially in the mountains. Sericulture (raising silkworms) and apiculture (beekeeping) were also well developed. Honey and wax from Zagore were considered the best in Byzantine markets.

More towns meant more growth in handicrafts, metalwork, and mining. Processing crops into bread, cheese, butter, and wine was common. Salt was taken from the lagoon near Anchialus. Leatherwork, shoemaking, carpentry, and weaving were important crafts. Varna was known for processing fox fur for fancy clothes. Western European sources said there was a lot of silk in Bulgaria. There were also blacksmiths and engineers who built siege equipment like catapults. Metalworking was strong in western Bulgaria, as well as in Tarnovo.

Money circulation and coin making steadily increased. They reached their highest point during the rule of Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria (1331–1371). Emperor Kaloyan (1197–1207) got the right to mint coins. Well-organized mints started in the mid-1200s, making copper, billon, and silver coins. This helped stabilize the money market. However, the Uprising of Ivaylo and Mongol raids in the late 1200s caused problems, reducing coin making. With the empire's stability from 1300, Bulgarian monarchs issued more coins. By the 1330s, they could supply the market with their own coins. Along with Bulgarian coins, coins from the Byzantine Empire, Venice, Serbia, and other places were widely used.

Religion

Religious Policy

After Bulgaria was re-established, getting the emperor's title recognized and restoring the Bulgarian Patriarchate were top goals. The constant wars with the Byzantine Empire led Bulgarian rulers to turn to the Pope. In his talks with Pope Innocent III, Kaloyan (1197–1207) asked for an imperial title and a Patriarchate. He based his claims on the history of the First Bulgarian Empire. In return, Kaloyan promised to accept the Pope's authority over the Bulgarian Church.

The union between Bulgaria and Rome became official on October 7, 1205. Kaloyan was crowned King by a papal representative, and Archbishop Basil of Tarnovo was named Primate. In a letter to the Pope, Basil called himself Patriarch, and the Pope did not object. Like Boris I three centuries earlier, Kaloyan used these talks for political reasons, not because he truly wanted to convert to Roman Catholicism. The union with Rome lasted until 1235. It did not change the Bulgarian church's practices, which continued to follow Eastern Orthodox rules.

Bulgaria wanted to be the religious center of the Orthodox world. After Constantinople fell to the Crusaders in 1204, Tarnovo became the main center of Orthodoxy for a while. Bulgarian emperors eagerly collected relics of Christian saints to boost their capital's importance. The official recognition of the restored Bulgarian Patriarchate in 1235 was a big step. It led to the idea of Tarnovo as a "Second Constantinople." The Patriarchate strongly opposed the Pope's idea to reunite the Orthodox Church with Rome.

Hesychasm

Hesychasm is a prayer tradition in the Eastern Orthodox Church that became popular in the Balkans in the 1300s. It's a mystical movement that taught a way of mental prayer. When repeated with proper breathing, it could help someone see a divine light. Emperor Ivan Alexander (1331–71) was impressed by Hesychasm. He supported Hesychastic monks. In 1335, he gave refuge to Gregory of Sinai and helped build a monastery. This monastery attracted religious people from Bulgaria, Byzantium, and Serbia.

Hesychasm became the main idea of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. A student of Gregory of Sinai, Theodosius of Tarnovo, translated his writings into Bulgarian. Hesychasm reached its peak during the time of the last medieval Bulgarian patriarch, Euthymius of Tarnovo (1375–94). Theodosius founded the Kilifarevo Monastery near Tarnovo. This became the new center for Hesychastic ideas and writing in Bulgaria. Hesychastic thinkers stayed in touch with each other, no matter their nationality. This greatly helped cultural and religious exchange in the Balkans.

Bogomilism and Other Beliefs

Bogomilism was a religious group that started in the 900s during the First Bulgarian Empire. It later spread throughout the Balkans. The Eastern Orthodox Church saw the Bogomils as heretics. They taught civil disobedience, which worried the government.

Bogomilism became popular again in Bulgaria because of military and political problems during the rule of Boril (1207–18). The emperor took strong steps to stop the Bogomils. On February 11, 1211, he led the first anti-Bogomil synod in Bulgaria. During the meeting, the Bogomils were identified. Those who did not return to Orthodoxy were sent away. As a result of Boril's actions, the Bogomils' influence greatly decreased.

Many other religious movements, like Adamites, came to Bulgaria with exiles from the Byzantine Empire. These movements, along with Bogomilism and Judaism, were condemned by the Council of Tarnovo in 1360. This council was attended by the imperial family, the patriarch, nobles, and religious leaders. There are no records of Bogomils in Bulgaria after 1360. This suggests the group had already become very weak.

Culture and Arts

The Second Bulgarian Empire was a center of rich culture. It reached its peak in the mid-to-late 1300s under Emperor Ivan Alexander (1331–71). Bulgarian architecture, arts, and literature spread to other Slavic countries like Serbia, Wallachia, Moldavia, and the Russian principalities. Bulgaria was also influenced by Byzantine culture. The main cultural and spiritual center was Tarnovo. It became known as a "Second Constantinople" or "Third Rome." Other important cultural places included Vidin, Sofia, and many monasteries.

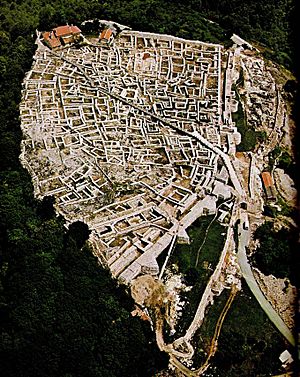

Architecture

More cities grew in the Second Bulgarian Empire during the 1200s and 1300s. New towns became important centers. Cities were usually built in hard-to-reach places. They often had an inner and outer town. Nobles lived in the inner town, which had a fortress. Most citizens lived in the outer town. There were separate areas for nobles, craftspeople, merchants, and foreigners. The capital, Tarnovo, had three fortified hills.

Fortresses were built on hills and plateaus. They were made with crushed stones held together with plaster. Gates and weaker parts were protected with towers. These towers were usually rectangular, but some were circular or other shapes.

Religious buildings were very important and well-decorated. During the 1200s and 1300s, older church styles were replaced with domed churches. The outside of churches had rich decorations. They used alternating layers of stone and brick. They were also decorated with green, yellow, and brown ceramic pieces. This style can be seen in churches in Messembria. A rectangular bell tower above the entrance was common for the architecture of the Tarnovo Artistic School.

The Church of the Holy Mother of God in Donja Kamenica (modern Serbia) has an unusual style. Its twin towers have sharp, pointed tops. This design was new for Bulgarian church architecture and was influenced by Hungary.

The Imperial Palace in Tarnovo was first a noble's castle. It was rebuilt twice. The palace was shaped like an uneven oval and covered a large area. Its walls were thick. The entrances were guarded by towers. The buildings were around a central courtyard with a royal church. The Patriarch's Palace was on the highest point of Tarnovo and overlooked the city.

Few noble houses have survived. The foundations of a noble house from the early 1200s have been found. It was L-shaped and had a living area and a small church. There were two types of common houses: semi-underground and above-ground. Above-ground houses in cities usually had two stories.

Art

The main style of Bulgarian art in the 1200s and 1300s is called the painting of the Tarnovo Artistic School. It was influenced by Byzantine art but had its own unique features. This school's works showed some realism and individual portraits. Very little non-religious art from this time has survived.

The frescoes in the Boyana Church near Sofia are an early example of this art, from 1259. They are some of the best-preserved medieval art in Eastern Europe. The portraits of the church's supporters and the ruling emperor and his wife are very realistic. The Rock-hewn Churches of Ivanovo also show the development of Bulgarian art. Both Boyana Church and the Rock-Hewn Churches of Ivanovo are on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

In Tarnovo, no complete art sets have survived. Fragments of frescoes were found in the ruins of churches in Tarnovo. The palace chapel was decorated with mosaics. In western Bulgaria, the art had older styles and simple colors.

Many books from the Second Bulgarian Empire had beautiful miniature paintings. Important examples include the Bulgarian translation of the Manasses Chronicle, the Tetraevangelia of Ivan Alexander, and the Tomić Psalter. These books have hundreds of miniatures. The style of these miniatures was influenced by Byzantine works.

The Tarnovo school continued the traditions of the First Bulgarian Empire's icon designs. Notable icons include St Eleusa (1342) and St John of Rila (14th century). Like the Boyana Church frescoes, St John of Rila uses realism. Some icons have silver coverings with enamel images of saints.

Literature

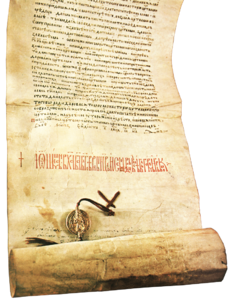

Churches and monasteries were the main places for writing and learning. They provided basic education. Some monasteries offered more advanced studies, including Greek language. Education was open to everyone, not just religious people. Those who finished advanced studies were called gramatik. Books were first written on parchment. Paper was introduced in the early 1300s. At first, paper was more expensive, but its cost fell later, leading to more books being made.

Few texts from the 1100s and 1200s have survived. Important examples include the "Book of Boril," which is a key source for Bulgarian history. Two poems written by a Byzantine poet at the Tarnovo court, about Emperor Ivan Asen II's wedding, have also survived.

In the 1300s, writing was supported by the court, especially by Emperor Ivan Alexander (1331–71). This, along with many skilled scholars, led to a great literary revival called the Tarnovo Literary School. Nobles and wealthy citizens also supported literature. Literature included translations of Greek texts and new original works, both religious and non-religious. Religious books included praising letters, stories of saints, and hymns. Non-religious literature included chronicles, poetry, novels, and popular tales.

The first notable Bulgarian scholar of the 1300s was Theodosius of Tarnovo (died 1363). He was influenced by Hesychasm and spread these ideas in Bulgaria. His most famous student was Euthymius of Tarnovo (c. 1325 – c. 1403). Euthymius was Patriarch of Bulgaria from 1375 to 1393 and founded the Tarnovo Literary School. He was a very productive writer. Euthymius also led a major language reform that standardized Bulgarian spelling and grammar.

When the Ottomans conquered Bulgaria, many scholars and students of Euthymius moved away. They took their texts, ideas, and skills to other Orthodox countries. So many texts went to Russia that scholars talk about a "second South Slavonic influence" on Russia. Euthymius's close friend, Cyprian, became Metropolitan of Kiev and All Rus'. He brought Bulgarian literary styles to Russia. Another important Bulgarian who moved was Constantine of Kostenets. He worked in Serbia, and his biography of a Serbian ruler is considered a very important historical work.

Apocryphal literature, which dealt with topics not in official religious works, was popular in the 1200s and 1300s. There were also many fortune-telling books. Some included political ideas. The authorities condemned these books. However, they still spread to Russia.

See also

In Spanish: Segundo Imperio búlgaro para niños

In Spanish: Segundo Imperio búlgaro para niños

- Byzantine–Bulgarian wars

- Bulgarian–Latin wars

- Bulgarian–Ottoman wars

- Bulgarian–Hungarian wars

- Bulgarian-Serbian Wars

- Medieval Bulgarian royal charters

- Medieval Bulgarian army

- Medieval Bulgarian navy

- Medieval Bulgarian coinage

- White Wallachia

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |