Beekeeping facts for kids

Beekeeping (also called apiculture) is when people keep honey bee colonies. They usually keep them in special homes called hives. A beekeeper is a person who looks after bees. They do this to collect honey and other things bees make. These include beeswax, propolis, pollen, and royal jelly. Beekeepers also help bees pollinate crops. Sometimes, they even raise bees to sell to other beekeepers. A place where bees are kept is called an apiary or "bee yard."

People started collecting honey from wild bees about 10,000 years ago. Beekeeping in pottery pots began around 9,000 years ago in North Africa. Ancient Egyptian art from about 4,500 years ago shows people keeping bees. They used simple hives and smoke. Honey was stored in jars, and some were found in the tombs of pharaohs like Tutankhamun. It wasn't until the 1700s that Europeans learned enough about bees to build hives with movable combs. This meant they could get honey without harming the whole bee colony.

Contents

Why Do People Keep Bees?

In the past, people mostly kept bees for their honey. Today, beekeeping is also very important for crop pollination. Bees help plants grow fruits and vegetables. Beekeepers also collect other useful products. These include beeswax and propolis.

Each hive has only one queen bee. She is bigger than all the other bees. The queen lays all the eggs. This means all the other bees in the hive are her children. But they do not control the hive.

Different Ways to Keep Bees

Some beekeeping is done by big farms. These are businesses that make money from bees. Other people keep bees as a hobby. This means they do it for fun.

Keeping bees in cities is becoming popular. This is called urban beekeeping. Some people have found that "city bees" are actually healthier. This is because cities often have fewer pesticides. They also have more different kinds of plants for bees to visit.

A Look at Beekeeping History

At some point, humans started trying to keep wild bees in special homes. These early hives were made from hollow logs, wooden boxes, or clay pots. Some were even woven straw baskets called "skeps." We know this because traces of beeswax have been found in old pottery. These traces date back to about 7000 BCE in the Middle East.

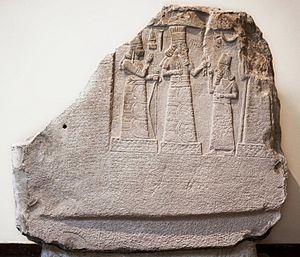

Beekeeping in Ancient Egypt

Honeybees were kept in Egypt a very long time ago. Pictures on the walls of the sun temple of Nyuserre Ini show workers blowing smoke into hives. This was done while they took out honeycombs. This was before 2422 BCE. Writings about making honey are found in the tomb of Pabasa (around 650 BCE). These show honey being poured into jars and round hives. Jars of honey were even found in the tomb of pharaohs like Tutankhamun.

Bees in Ancient Greece and Israel

In ancient Greece, especially on Crete and in Mycenae, beekeeping was very important. People have found old hives, smoke pots, and tools for honey. Beekeeping was a respected job.

Archaeologists found old beekeeping tools at Rehov in Israel. They found 30 hives made of straw and clay. These hives were found in neat rows and date back to about 900 BCE. There could have been about 100 hives, holding over 1 million bees. This shows that ancient Israel had a big honey industry 3,000 years ago.

Beekeeping Around the World

In ancient Greece, Aristotle wrote a lot about bees and beekeeping. Roman writers like Virgil also wrote about it.

Beekeeping was also done in ancient China. A book from the Spring and Autumn period (around 771-476 BCE) talks about how to keep bees. It said that the quality of the wooden box used for the hive was important.

The ancient Maya in Central America kept a different kind of bee. These were stingless bees. This type of beekeeping is called meliponiculture. It is still done today in places like Brazil and Australia.

Where Do Bees Come From?

There are over 20,000 types of wild bees. Many bees live alone, like mason bees. Others live in small groups, like bumblebees. Some honey bees are wild, like the giant honeybee.

Beekeeping focuses on social honey bees. These bees live in very large groups, sometimes up to 100,000 bees! In Europe and America, beekeepers mostly manage the Western honey bee. This bee has different types, like the Italian bee. In warmer places, other honey bees are kept, such as the Asiatic honey bee.

Collecting Wild Honey

Collecting honey from wild bees is one of the oldest human activities. People still do this in parts of Africa, Asia, and South America. In Africa, special honeyguide birds help humans find bee nests. This shows that humans have been collecting wild honey for a very long time.

Early cave paintings from around 13,000 BCE show people gathering honey. To get honey from wild nests, people often use smoke to calm the bees. Then they break open the tree or rocks where the nest is. This often destroys the nest.

Learning About Honey Bees

It wasn't until the 1700s that scientists really started to study bees. People like Jan Swammerdam and René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur used microscopes to learn about bees' bodies. Réaumur even built a hive with glass walls to watch the bees.

A blind scientist named François Huber made huge discoveries. He used a secretary, François Burnens, to help him observe bees for over 20 years. Huber proved that queens mate with male drones outside the hive, high in the air. He also showed that a queen mates with several drones. Huber is known as "the father of modern bee-science." His book, "New Observations on Bees," explained many basic facts about bee biology.

The Movable Comb Hive

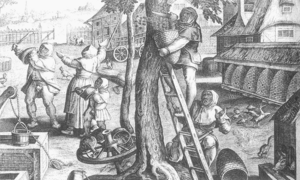

Before, when people collected honey, they often destroyed the whole bee colony. They would break into the wild hive, use smoke, and tear out the honeycombs. This destroyed the eggs, young bees, and honey. The liquid honey was then strained. This was messy and bad for the bees. It meant beekeeping was not a continuous activity.

During the Middle Ages, monasteries were important for beekeeping. Beeswax was needed for candles. Fermented honey was used to make mead, an alcoholic drink.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, beekeeping changed a lot. People learned how to get honey without killing the bees. Thomas Wildman, in the 1760s, described hives where bees built combs on wooden bars. This was a step towards modern hives. He also talked about stacking hives, like modern "supers."

But the biggest change came from an American named Lorenzo Langstroth.

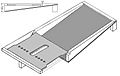

Langstroth was the first to use a special discovery. He learned that bees leave a specific small space between their wax combs. This space is called the bee space. It is about 5 to 8 millimeters (1/4 to 3/8 inches). Bees do not fill this space with wax.

Langstroth then designed wooden frames that fit into a rectangular hive box. He made sure there was always the correct bee space between the frames. Bees built their honeycombs on these frames without sticking them to each other or the hive walls. This meant beekeepers could slide any frame out to check on the bees. They could do this without harming the bees or the comb. Honey could be taken out without destroying the comb. Empty combs could be put back for the bees to refill. Langstroth's book, The Hive and Honey-bee, published in 1853, explained his ideas.

This invention helped commercial honey production grow a lot.

How Hive Designs Changed

Langstroth's design was quickly used by beekeepers everywhere. Many different movable comb hives were made in England, France, Germany, and the United States. Each country developed its own popular designs. For example, Dadant and Langstroth hives are common in the USA.

Hives are usually made of cedar, pine, or cypress wood. But now, hives made from strong polystyrene foam are also used.

Hives often have a "queen excluder." This is a screen that keeps the queen from laying eggs in the parts of the hive where honey is stored for people to eat. Also, because of tiny pests called mites, many hives now have wire mesh floors.

Traditional Beekeeping Methods

Hives with Fixed Combs

A fixed comb hive is one where the combs cannot be removed without damaging them. Almost any hollow space can be used, like a hollow log or a clay pot. Fixed comb hives are not common in modern countries. In many places, they are even against the law. This is because beekeepers need to check for diseases like varroa mites.

However, in many developing countries, fixed comb hives are still used. They are cheap to make from local materials. Beekeeping with these hives helps many communities earn a living.

Modern Beekeeping Methods

Top-Bar Hives

Top-bar hives are popular in Africa. They are light and easy to use. It is also easier to collect honey from them. One downside is that the combs are delicate. They cannot usually be put back after the honey is taken. This means less honey might be produced.

More and more hobby beekeepers are using top-bar hives. These hives have no frames. The honey-filled comb is not returned after honey is taken. This type of hive has been used for over 2000 years in Greece and Vietnam.

Top-bar hives are cheaper to start. They also make it easier to work with bees. You don't have to lift heavy boxes. These hives are widely used in developing countries.

Horizontal Frame Hives

Hives like the De-Layens hive are used in Spain, France, and parts of Russia. These hives have movable frames, which is an improvement. But their size is fixed and cannot be easily made bigger. Honey must be removed one frame at a time.

Vertical Stackable Frame Hives

In the United States, the Langstroth hive is very common. It was the first successful hive that opened from the top and had movable frames. Many other hive designs are based on Langstroth's idea of bee space.

In the United Kingdom, the British National hive is most common. Dadant hives are popular in France and Italy because they are large. The Rose hive is a newer design. The main benefit of these hives is that you can add more boxes of frames. This gives bees more space for brood and honey. It also makes honey collection easier because you can remove a whole box of honey at once.

Beekeeper's Tools and Safety

Protective Clothing

Most beekeepers wear some protective clothing. New beekeepers usually wear gloves and a suit with a hood or a hat and veil. Experienced beekeepers sometimes don't wear gloves. This is because gloves can make it harder to do delicate tasks.

It is most important to protect your face and neck. So, most beekeepers wear at least a veil. A sting on the face can hurt a lot more. A sting on a bare hand can often be quickly scraped off to reduce the venom.

Protective clothing is usually light-colored and smooth. This helps bees see that the person is not a dark, furry animal like a bear.

If a bee stings your clothing, the stinger can release a warning smell. This smell can attract more bees to sting. Washing suits often helps remove this smell.

If you get stung, quickly scrape off the stinger with your fingernail. Do not squeeze it, as this can push more venom into your skin. Wash the area with soap and water. Then, put ice or a cold pack on it.

The Smoker

Smoke is a very important tool for beekeepers. Most beekeepers use a "smoker." This tool makes smoke from burning different materials. Smoke calms bees. It makes them think there might be a fire, so they start eating honey. When bees eat honey, their bellies get full, which makes it harder for them to sting.

Smoke also hides the warning smells that guard bees release. This confusion allows the beekeeper to open the hive and work without getting stung.

You can use many natural materials in a smoker. These include hessian (a type of cloth), twine, pine needles, or rotten wood. Some beekeepers use "liquid smoke" spray as a safer option.

Different Styles of Beekeeping

Natural Beekeeping

The natural beekeeping movement believes that modern practices can weaken bee hives. These practices include moving hives often, using medicines, and feeding bees sugar water.

People who practice "natural beekeeping" often use top-bar hives. These are simple hives without frames. The horizontal top-bar hive is a modern version of old hollow log hives. It has wooden bars where bees build their combs. This method became popular after Philip Chandler's book, The Barefoot Beekeeper, was published in 2007.

Another popular natural hive is the Warré hive. It was designed by a French priest named Abbé Émile Warré.

Urban or Backyard Beekeeping

Urban beekeeping is about keeping bees in cities or backyards. It is a way to get honey without big industrial farms. Many people see urban beekeeping as a growing trend.

Some people have found that "city bees" are healthier than "rural bees." This is because cities often have fewer pesticides. They also have more different kinds of plants for bees. Homeowners can help city bees by planting flowers that provide nectar and pollen all year.

Indoor Beekeeping

Some modern beekeepers have tried raising bees indoors. They do this in a controlled environment. This can be for space reasons or to watch the bees closely. In winter, large beekeepers sometimes move colonies to special warehouses. These warehouses have controlled temperature, light, and humidity. This helps the bees stay healthy but mostly inactive.

Scientists have also experimented with keeping bees indoors for longer. At MIT, a project called Synthetic Apiary created a springtime environment indoors during winter. They provided food and long "days." The bees were active and reproduced like they would outdoors. This suggests that indoor beekeeping could be done all year if needed.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Apicultura para niños

In Spanish: Apicultura para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |