Croatia in personal union with Hungary facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Croatia (and Dalmatia)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1102–1526 | |||||||||

|

Coat of arms

(14th–15th century) Note: Later used for Dalmatia Coat of arms (late 15th–16th century) |

|||||||||

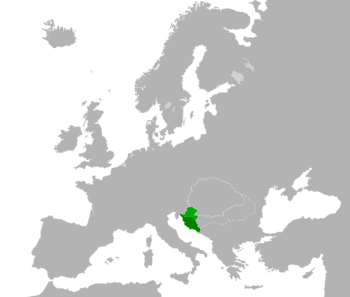

Kingdom of Croatia and Dalmatia (dark green) in 1260

|

|||||||||

| Status | In personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary (See historical context section) |

||||||||

| Capital | Biograd (until 1125) Knin (until 1522) |

||||||||

| Common languages | Latin, Croatian, Hungarian, | ||||||||

| Religion | Catholic Church | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Croatian, Croat | ||||||||

| Government | Feudal Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

|

• 1102–1116 (first)

|

Coloman | ||||||||

|

• 1516–1526 (last)

|

Louis II | ||||||||

| Ban (Viceroy) | |||||||||

|

• 1102–1105 (first)

|

Ugra | ||||||||

|

• 1522–1526 (last)

|

Ferenc Batthyány | ||||||||

| Legislature | Sabor | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

|

• Coronation of Coloman in Biograd

|

1102 | ||||||||

|

• Treaty of Zadar

|

18 February 1358 | ||||||||

|

• Battle of Krbava Field

|

9 September 1493 | ||||||||

|

• Fall of Knin

|

29 May 1522 | ||||||||

| 29 August 1526 | |||||||||

| Currency | Frizatik (12th–13th century) Banovac (1235–1384) |

||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | Croatia Bosnia and Herzegovina |

||||||||

The Kingdom of Croatia became part of a personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary in 1102. This happened after a time when Croatian kings ruled, followed by a period of trouble over who would be the next king.

In 1102, King Coloman was crowned "King of Croatia and Dalmatia" in Biograd. This meant that the Árpád dynasty from Hungary now ruled Croatia. This union lasted until 1301. After that, kings from the Capetian House of Anjou took over.

The centuries that followed were full of challenges. There were fights with the Mongols, who even attacked Zagreb in 1242. Croatia also competed with Venice for control of cities along the Dalmatian coast. There were also many internal wars among powerful Croatian noble families.

One important figure was Paul I Šubić of Bribir, who led the strong Šubić noble family. These powerful nobles sometimes managed to rule their lands almost like independent kings.

In the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire began to invade Europe. This greatly reduced Croatian lands and left the country weak. After King Louis II died in 1526 during the Battle of Mohács, both the Croatian and Hungarian crowns went to the Austrian House of Habsburg. This made Croatia part of the larger Habsburg monarchy.

Even though Croatia was united with Hungary, it kept its own special government. It had the Sabor (an assembly of Croatian nobles) and the Ban (a viceroy or governor). Croatian nobles also kept their lands and titles.

Contents

What was Croatia Called?

The official name of the kingdom was "Kingdom of Croatia and Dalmatia" in Latin (Regnum Croatiae et Dalmatiae). This name was used until 1359. After that, people started using the plural form "kingdoms" (regna).

This change happened because King Louis I won a big victory against the Republic of Venice. The Treaty of Zadar meant Venice lost its control over the Dalmatian coastal cities. However, the kingdom was still often called "Kingdom of Croatia and Dalmatia" until Venice got the coast back in 1409. In Croatian, the most common name was Hrvatska zemlja, meaning "Croatian country" or "Croatian land."

How Did Croatia Join Hungary?

The Search for a New King

Demetrius Zvonimir was a Croatian king from the House of Trpimirović. He married Helen of Hungary in 1063. Helen was a Hungarian princess and sister of King Ladislaus I of Hungary. They had a son, Radovan, who died young.

When King Zvonimir died in 1089, Stephen II became king. He was the last of the Trpimirović family. Stephen's rule was short and he died in 1091 without leaving an heir. This caused a big problem in Croatia, leading to civil war.

King Zvonimir's widow, Helen, tried to keep her power. Some Croatian nobles asked her brother, King Ladislaus I of Hungary, for help. They offered him the Croatian throne, believing he had a right to it through his sister.

In 1091, Ladislaus crossed the Drava river and took control of Slavonia. However, he couldn't conquer all of Croatia. He had to go back to Hungary because the Cumans attacked his kingdom. Ladislaus left his nephew, Prince Álmos, to rule the parts of Croatia he controlled.

Meanwhile, in 1093, Croatian nobles chose Petar Snačić as their new king. King Petar ruled from Knin. He fought against Álmos, who eventually had to leave Croatia.

The Coronation of Coloman

King Ladislaus died in 1095. His nephew, Coloman, continued the fight for the Croatian throne. In 1097, Coloman's army defeated King Petar's troops in the Battle of Gvozd Mountain. King Petar was killed in the battle.

Since Croatia no longer had a leader, and many coastal towns were hard to capture, Croatian nobles began talking with Coloman. After several years, the Croatian nobility accepted Coloman as their king.

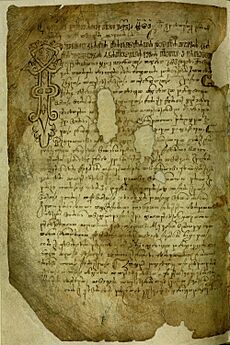

Coloman was crowned in Biograd in 1102. He then called himself "King of Hungary, Dalmatia, and Croatia." Some of the agreements made during his coronation are written in a document called Pacta Conventa. This document says that 12 Croatian noble families agreed to recognize Coloman as king. In return, they kept their lands and were free from taxes. They also agreed to send horsemen to help the king if his borders were attacked.

Even though the Pacta Conventa might not be the original document from 1102, historians believe there was an agreement that set up the relationship between Hungary and Croatia in a similar way.

How Croatia and Hungary Were Connected

The exact details of how Croatia and Hungary were united have been debated for a long time. Croatian historians believe it was a "personal union," meaning the two kingdoms simply shared the same king. Many Hungarian historians now agree with this view.

This union meant that Croatia kept its own government bodies. It had its own local governor, called a Ban, and an assembly of nobles, called the Sabor. Croatia also had its own laws and customs.

The level of Croatia's independence changed over the centuries. Sometimes it acted very independently, and other times it was more under Hungary's control. However, Croatia generally kept a good amount of freedom in its internal affairs.

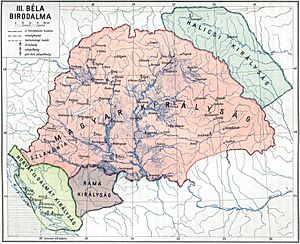

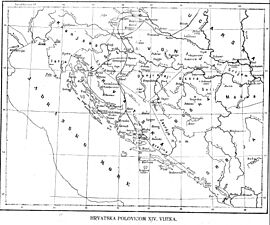

Geography and Administration

The Kingdom of Croatia stretched from the Kvarner Gulf in the north to the mouth of the Neretva river in the south. To the east, it was bordered by the Vrbas and Neretva rivers. To the north, it reached the Gvozd Mountain and the Kupa river.

Croatia was governed by a deputy for the king, called a ban. From 1198, Croatia and Slavonia were also ruled by Dukes of Croatia, who acted like semi-independent rulers. Under the duke, there was still a ban, who was usually a powerful nobleman.

At first, one ban ruled all Croatian areas. But after 1225, the territory was split into two parts, each with its own ban: the Ban of Croatia and Dalmatia, and the Ban of Slavonia. These two positions were sometimes held by the same person and officially merged back into one in 1476.

Croatia was divided into smaller areas called counties (županije). Each county was led by a count (župan). These Croatian counts were local nobles who inherited their positions and ruled according to Croatian laws.

Key Historical Events

Fights with Venice and Byzantium

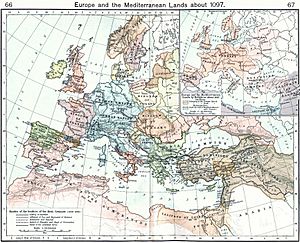

By 1107, King Coloman controlled most of the important coastal cities in Dalmatia. These cities were very valuable, so Hungarians and Croats often fought with Venice and the Byzantines for control of the region.

In 1116, after Coloman died, Venice attacked the Dalmatian coast. They captured Biograd, Split, Trogir, Šibenik, Zadar, and several islands. King Stephen II tried to get these cities back but didn't succeed at first.

Over the next few decades, there were many battles and truces. Cities like Zadar often rebelled against Venice. In 1202, during the Fourth Crusade, the Venetians and Crusaders attacked and sacked Zadar. This was unusual because Zadar was a Catholic city.

Hostilities with Venice continued for many years.

Powerful Noble Families

In the 12th century, powerful noble families became very important in Croatia. These families were mostly descendants of the original twelve noble Croatian tribes. They held and managed whole counties, ran local courts, and made their own decisions.

Some of the most important noble families were:

- The Šubić (Princes of Bribir), who ruled inland Dalmatia from their base in Bribir.

- The Babonić in western Slavonia.

- The Kačić, known for being pirates, between the Cetina and Neretva rivers.

- The Frankopan (Princes of Krk), who ruled the island of Krk.

During this time, Christian military orders like the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller also gained a lot of land in Croatia.

Mongol Invasion of Croatia

During the rule of King Béla IV, the Mongols (also called Tatars) invaded Hungary in 1241. They defeated the Hungarian army. King Béla fled to Croatia to escape them.

In 1242, the Mongols crossed the Drava river and started attacking Croatian lands. They sacked towns like Čazma and Zagreb, burning its cathedral. The king and nobles moved south to strongholds like fortress of Klis, Split, and Trogir. The Mongols tried to capture Klis but failed.

Soon, news arrived that the Mongol leader, Ögedei Khan, had died. The Mongols turned back to choose a new leader. One group went through Zeta, Serbia, and Bulgaria, looting as they went. Another group attacked the area around Dubrovnik and burned Kotor.

After the Mongols left, Croatia was devastated, and there was a great famine. The invasion showed that only fortified cities could protect people. So, work began on building new defenses and repairing old ones. Many new castles were built, like Medvedgrad above Zagreb. King Béla IV also made Gradec (part of modern Zagreb) a free royal city, giving its citizens special rights.

Civil War in the 13th Century

The Mongol invasion briefly stopped the internal fighting among nobles. But after the Mongols left in the 1240s, a civil war broke out in Croatia. The main reason was a dispute between Split and Trogir over a village called Ostrog.

King Béla IV tried to prevent future wars by giving the power to elect city governors to the Ban of Croatia, instead of the cities themselves. However, the powerful Šubić family was not happy with this decision.

Over time, local nobles continued to grow stronger. The weakening of royal power allowed the Šubić family to regain control over many coastal cities. In the 1270s, Paul I Šubić of Bribir became the head of the family and was soon named the Ban of Croatia and Dalmatia. His brothers became princes of important Dalmatian cities.

Dynastic Struggles and the Šubić Family's Power

In 1290, King Ladislaus IV died without sons, leading to a fight over who would be the next king. Croatian Ban Paul Šubić supported Charles Martel of Anjou. To gain Croatian support, Charles Martel's father promised Paul Šubić all lands from the Gvozd Mountain to the Neretva River. This made the position of ban hereditary for the Šubić family.

Paul Šubić became the most powerful family in Croatia. He even gained control over Bosnia in 1299, calling himself "Ban of the Croats and Lord of Bosnia." He appointed his brother, Mladen I Šubić, as Ban of Bosnia. Paul's power stretched from the Gvozd Mountain to the Neretva River, and from the Adriatic coast to the Bosna River. Only Zadar remained under Venetian rule.

Paul even minted his own money and acted like an independent ruler. In 1311, he helped Zadar rebel against Venice. When Paul died in 1312, his son Mladen II took over. However, the Šubić family's power began to decline.

In 1322, another civil war started in Croatia. Mladen II and his allies were defeated by other Croatian nobles and coastal towns. The king then ended the hereditary rule of the Šubić family. Their lands were reduced.

After the Šubić family's decline, Ivan Nelipić became the dominant figure in Croatia. He took control of the royal city of Knin. This meant that much of Croatia was outside the king's direct control. Nelipić ruled independently from Knin until his death in 1344. After his death, King Louis I restored royal power in Croatia.

Changes in Dalmatia

In 1345, Zadar rebelled against Venice again. After a long siege, Venice regained the city in 1346. King Louis I signed a peace treaty with Venice in 1348.

In 1356, King Louis attacked Venetian territories. Croatian army, led by Ban John Csúz, helped. Split, Trogir, and Šibenik soon got rid of Venetian governors, and Zadar fell after a short siege. Venice was forced to sign the Treaty of Zadar on February 18, 1358.

With this treaty, King Louis gained control over all of Dalmatia, including Dubrovnik (Ragusa), which acted as an independent city. The Doge of Venice had to give up his title "Duke of Croatia and Dalmatia." After this, all Croatian territory was united under one administration, led by the Ban of Croatia and Dalmatia. This led to a period of economic growth in Croatia, especially in the coastal cities.

Anti-Royal Movements

After King Louis I died in 1382, his wife Elizabeth of Bosnia became regent for their young daughter, Queen Mary. Some nobles disagreed with Queen Mary becoming ruler.

In Croatia, John of Palisna led a rebellion against Elizabeth. He was joined by Tvrtko I of Bosnia, who had been crowned King of Bosnia in 1371. John was defeated and fled to Bosnia.

Later, in 1385, a new movement against Queen Mary and Elizabeth started. It was led by John Horvat and his brother Paul Horvat. They were joined by John of Palisna. They supported Charles III of Naples as the rightful king. Charles briefly became king, but Elizabeth had him murdered in 1386.

The Horvat brothers then rebelled again, supporting Charles's son, Ladislaus of Naples. They captured Queen Mary and Elizabeth. Elizabeth was later murdered in prison. Sigismund of Luxemburg, Queen Mary's husband, was crowned king in 1387.

King Tvrtko I of Bosnia and his allies, including Hrvoje Vukčić Hrvatinić, gained control of most of Croatia and Dalmatia between 1387 and 1390. Tvrtko even called himself "King of Croatia and Dalmatia."

After Tvrtko died in 1391, Hrvoje Vukčić Hrvatinić became the strongest nobleman in Bosnia. Ladislaus appointed him as his deputy in Dalmatia and gave him the title of Duke of Split.

The situation changed in 1393 when Tvrtko's successor, Stephen Dabiša, made peace with Sigismund. Hrvoje Vukčić also submitted to Sigismund. In 1394, Sigismund captured John Horvat, ending the Horvat uprising. John was later murdered.

In 1397, Sigismund called a meeting in Križevci, Croatia. At this meeting, Stephen II Lackfi, who was Ladislaus's deputy for Croatia, was murdered along with other nobles. This event became known as the "Bloody Sabor of Križevci" and started a new uprising led by Hrvoje Vukčić.

Hrvoje was very powerful and resisted Sigismund's military actions for years. However, Ladislaus's lack of action disappointed his followers. Many Hungarian and Croatian nobles, including the Frankopans, eventually sided with Sigismund. In 1409, Ladislaus sold his rights in Dalmatia to Venice for a large sum of money.

Ottoman Wars and Croatian Resistance

After the Ottoman Empire conquered the Byzantine Empire in 1453, they quickly moved westward and threatened Croatia. Following the fall of the Kingdom of Bosnia in 1463, King Matthias Corvinus built stronger defenses.

Even though the Ottomans had trouble breaking through these defenses, they regularly raided Croatia and southern Hungary. In 1463, Croatian Ban Pavao Špirančić was captured during one such raid. The Ottomans expanded rapidly into southern areas, conquering parts of Herzegovina in 1482.

Croatia achieved its first major victory over the Ottomans in 1478, led by Count Petar Zrinski near Glina. In 1483, a Croatian army defeated about 7,000 Ottoman cavalry near modern-day Novi Grad. A peace treaty was signed that year, which reduced large Ottoman raids.

The peace ended when Matthias Corvinus died in 1490. In 1491, 10,000 Ottoman cavalry raided Carniola and were defeated on their way back. Two years later, a war started between the new Ban of Croatia, Emerik Derenčin, and the Frankopan family. They made peace when an Ottoman army, returning from a raid, entered Croatia.

Croatian nobles gathered about 10,000 men and decided to fight the Ottomans in an open battle. On September 9, 1493, the Croatian army was heavily defeated in the Battle of Krbava Field. Although it was a big loss, the Ottomans did not gain any territory from this battle. Many Croatian people from the affected areas moved to safer parts of the country or fled to other regions like Burgenland and Italy.

On August 16, 1513, Ban Petar Berislavić defeated an Ottoman army of 7,000 men. In February 1514, the Ottomans besieged Knin but failed to capture it. In 1519, Pope Leo X called Croatia the forefront of Christianity (Antemurale Christianitatis) because Croatian soldiers contributed greatly to the fight against the Ottomans.

Petar Berislavić fought the Ottomans for seven years, often facing money problems and too few troops. He was killed in an ambush on May 20, 1520. After two failed attempts, Ottoman forces led by Gazi Husrev-beg finally captured Knin on May 29, 1522. They also tried to capture Klis Fortress many times, but its captain, Petar Kružić, defended it for almost 25 years.

On April 23, 1526, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent began his invasion of Hungary. He reached the Sava river in July and captured Petrovaradin and Ilok. On August 23, his troops crossed the Drava river without resistance. King Louis II arrived at Mohács with about 25,000 men. Count Christopher Frankopan's army of 5,000 men did not arrive in time.

The Hungarian army waited for the Ottomans on the plain south of Mohács on August 29. They were completely defeated in less than two hours. The 1526 Battle of Mohács was a crucial event. King Louis II died, ending the rule of the Jagiellon dynasty. This defeat showed that the Christian armies were struggling to stop the Ottomans, who would remain a major threat for centuries.

The 1527 Parliament of Cetin

King Louis II had held the crown of Croatia, but he died without an heir. After his death, the Hungarian Diet (assembly) chose John Zápolya as king. However, another Hungarian assembly chose Archduke Ferdinand I of Austria.

Ferdinand wanted to be king of Croatia to oppose Zápolya. He promised to protect Croatia from the Ottomans. The Croatian nobles met on December 31, 1526, to decide their future. At an assembly in the Franciscan monastery below the Cetin Castle on January 1, 1527, the Croatian parliament unanimously elected Ferdinand of the House of Habsburg as King of Croatia. The document confirming Ferdinand's election was sealed by six Croatian nobles and four of Ferdinand's representatives.

However, on January 6, 1527, the nobility from Slavonia sided with John Zápolya.

Croatian historians say that the decision to join the Habsburg Empire was a free choice made by the Sabor. Austrian historians agree with this view. The political situation after the Battle of Mohács – with the king's death, two elected rulers, and Ottoman conquests – completely changed the medieval relationship system. A civil war broke out between Ferdinand's and Zápolya's supporters. This war ended with an agreement that benefited Ferdinand, and both crowns were united under the Habsburgs. While this technically restored a Croatian-Hungarian union, the relationship between the two countries changed forever.

Croatian Symbols

The first known symbol for Croatia, from the late 12th century, was a six-pointed star over a crescent moon. This was found on a Croatian coin called a Frizatik, minted by Andrew II.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the symbol that is now the coat of arms of Dalmatia was used to represent the Kingdom of Croatia. This symbol shows three crowned lion heads on a blue shield. It appeared in many old books of coats of arms and on coins and seals of kings.

The famous Croatian checkerboard design began to be used in the late 15th century. By the early 16th century (1525), it became the official symbol of Croatia. It usually had five rows of five interlocking silver and red squares. It was also used as a military flag at the Battle of Mohács.

See also

- Kingdom of Croatia before union with Hungary

- Hundred Years' Croatian–Ottoman War

- Bans of Croatia