Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Croatia

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 925–1102 | |||||||||||

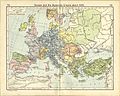

Croatia during the reign of King Tomislav in purple and vassal states in light purple

|

|||||||||||

| Capital | Varied through time Nin Biograd Solin Knin |

||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Croatian Old Church Church Slavonic Latin |

||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Croatian, Croat | ||||||||||

| Government | Feudal Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

|

• 925–928 (first)

|

Tomislav | ||||||||||

|

• 1093–1097 (last)

|

Petar Snačić | ||||||||||

| Ban (Viceroy) | |||||||||||

|

• c. 949–969 (first)

|

Pribina | ||||||||||

|

• c. 1075–1091 (last)

|

Petar Snačić | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

|

• Elevation to kingdom

|

c. 925 | ||||||||||

| 1102 | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

The Kingdom of Croatia (in Croatian: Kraljevina Hrvatska; in Latin: Regnum Croatiae) was a medieval kingdom in Southern Europe. It included most of what is now Croatia and much of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. This kingdom was a sovereign state for almost 200 years.

During its existence, the Kingdom of Croatia had many conflicts and peaceful times. It interacted with the Bulgarians, Byzantines, Hungarians, and Venice. Venice and Croatia often competed for control over the eastern Adriatic coast. In the late 11th century, Croatia gained control of most coastal cities in Dalmatia. This happened as Byzantine power in the region weakened. The kingdom was strongest under kings Peter Krešimir IV (1058–1074) and Demetrius Zvonimir (1075–1089).

The Trpimirović dynasty mostly ruled the state until 1091. After this, there was a succession crisis. For ten years, different groups fought for the throne. Eventually, the crown went to the Árpád dynasty of Hungary. King Coloman of Hungary was crowned "King of Croatia and Dalmatia" in Biograd in 1102. This event united the two kingdoms under one ruler.

Historians in the 19th century debated the exact relationship between Croatia and Hungary. Today, most Croatian and Hungarian historians see it as a personal union. This means the two kingdoms were separate but shared the same king. Croatia kept a lot of its own internal control. Real power often stayed with the local nobles.

Contents

Kingdom of Croatia: Its Name and History

The first official name of the country was "Kingdom of the Croats." This was Regnum Croatorum in Latin and Kraljevstvo Hrvata in Croatian. Over time, the name "Kingdom of Croatia" became more common.

How the Name Changed

From 1060, King Peter Krešimir IV took control of coastal cities that were once part of the Byzantine Empire. After this, the kingdom's official name became "Kingdom of Croatia and Dalmatia." This name was used until King Stephen II died in 1091.

Early Croatian History

Before becoming a kingdom, the area was known as the Duchy of Croatia. The Slavs arrived in southeastern Europe in the early 7th century. They formed several states, including this duchy.

Christian Faith in Croatia

The Croats started becoming Christians soon after they arrived. By the early 9th century, most were Christian. The duchy was ruled by two main families: the Domagojević and Trpimirović dynasties. It often competed with the nearby Republic of Venice. It also fought and allied with the First Bulgarian Empire. Sometimes, it was under the control of the Carolingian Empire or the Byzantine Empire. In 879, Pope John VIII recognized Duke Branimir as an independent ruler.

The Kingdom is Born

Croatia officially became a kingdom around 925. Tomislav was the first Croatian ruler to be called "king" by the Pope.

King Tomislav's Reign

It is believed that Tomislav was crowned in 925. However, we don't know exactly when, by whom, or even if he had a formal coronation. Documents from that time, like the Historia Salonitana, mention Tomislav as a "king." A letter from Pope John X also calls him "King of the Croats." Later rulers in the 10th century also used the title "king." Under Tomislav, Croatia grew into one of the most powerful kingdoms in the Balkans.

Tomislav was a key member of the Trpimirović dynasty. Between 923 and 928, he united the Croats from different regions. These regions included Pannonia and Dalmatia. Croatia likely covered most of Dalmatia, Pannonia, and parts of Bosnia. The kingdom was divided into eleven counties (županije) and one special area called a banate. Each region had a fortified royal town.

Conflicts and Alliances

Croatia soon faced conflicts with the Bulgarian Empire. The Bulgarian ruler, Simeon I, was already at war with the Byzantines. Tomislav made an agreement with the Byzantine Empire. This alliance might have given him control over some coastal cities and a share of their taxes.

In 924, Simeon conquered Serbia. Croatia then welcomed and protected the Serbs who were forced to leave their homes. In 926, Simeon tried to attack Croatia and the Byzantine lands. However, his army was defeated by Tomislav's forces in the Battle of the Bosnian Highlands. After Simeon's death in 927, peace was made between Croatia and Bulgaria. This was thanks to the Pope's representatives.

Ancient records suggest that Croatia had a very large army and navy at this time. Some historians believe these numbers might be exaggerated. However, it shows that Croatia was seen as a strong military power.

Changes in the 10th Century

Croatian society changed a lot in the 10th century. Local leaders were replaced by the king's followers. These new leaders took land from others, which led to a feudal system. Many free farmers became serfs, meaning they were tied to the land. This change also made Croatia's military weaker.

Rulers After Tomislav

Tomislav was followed by Trpimir II (around 928–935) and Krešimir I (around 935–945). They managed to keep their power and good relations with the Byzantine Empire and the Pope.

The rule of Krešimir's son, Miroslav, saw Croatia weaken. Some areas broke away from the kingdom. Miroslav was killed during a power struggle. His ban (a high official), Pribina, helped Michael Krešimir II (949–969) become king. Michael Krešimir II brought order back to most of the state. He and his wife, Helen, had good relations with the coastal cities. Helen built a church in Solin that became the burial place for Croatian rulers. An inscription on her tomb called her "Mother of the Kingdom."

Michael Krešimir II's son, Stephen Držislav (969–997), improved relations with the Byzantine Empire. He received royal symbols from the Byzantines. From his time, his successors called themselves "kings of Croatia and Dalmatia."

The 11th Century: Growth and Challenges

When Stephen Držislav died in 997, his three sons fought for the throne. This weakened Croatia. It allowed Venice and the Bulgarians to take control of Croatian lands along the Adriatic.

Venetian and Byzantine Influence

In 1000, the Venetian fleet took control of many islands and cities along the eastern Adriatic coast. King Krešimir III tried to get the Dalmatian cities back. He had some success until 1018, when Venice, allied with the Lombards, defeated him. His kingdom then briefly became a vassal (under the control) of the Byzantine Empire until 1025.

King Peter Krešimir IV

During the rule of Krešimir IV (1058–1074), the Croatian kingdom reached its largest size. The Byzantine Empire recognized him as the ruler of the Dalmatian cities. Croatia under Krešimir IV had twelve counties. It included the southern duchy of Pagania, and its influence reached over Zahumlje, Travunia, and Duklja.

The Roman Catholic Church introduced reforms in Croatia. These reforms banned the use of Slavonic language in church services and made Latin mandatory. This led to a rebellion in some parts of the kingdom, especially in the Kvarner region. King Krešimir IV supported the Pope. Even though the rebellion was quickly stopped, Slavonic church services and the Glagolitic script continued to be used in the Kvarner region.

In 1072, Krešimir helped a rebellion against the Byzantines. In return, the Byzantines sent Norman forces to attack Croatia in 1074. The Normans captured King Krešimir himself. Croatia was forced to give up several important cities to the Normans. In 1075, Venice drove out the Normans and took control of these cities. Krešimir IV's death in 1074 marked the end of the Trpimirović dynasty's direct rule.

King Demetrius Zvonimir

Demetrius Zvonimir (1075–1089) became the next king. He was crowned in Solin on October 8, 1076, with the support of Pope Gregory VII. Zvonimir helped the Normans in their fight against the Byzantine Empire and Venice. Because of this, the Byzantines gave their rights in Dalmatia to Venice in 1085.

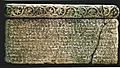

Zvonimir's rule is recorded on the Baška Tablet. This is one of the oldest written Croatian texts. His time as king is remembered as peaceful and prosperous. The connection between Croats and the Catholic Church became stronger during his reign. Croatian noble titles became similar to those used in other parts of Europe. Croatia was moving closer to Western Europe.

King Demetrius Zvonimir married Helen of Hungary in 1063. She was a Hungarian princess and the sister of the future Hungarian King Ladislaus I. Zvonimir died in 1089. The exact cause of his death is unknown. Some legends say he was killed during a revolt.

The kingdom did not have a single, permanent capital city. The royal residence changed with each ruler. Five cities were known as royal seats: Nin, Biograd, Knin, Šibenik, and Solin.

The Succession Crisis

Stephen II (1089–1091) was the last king from the main Trpimirović line. He was old when he became king and ruled for less than two years. He died in early 1091 without leaving an heir. Since there were no other male members of the Trpimirović family, a civil war began.

Hungarian Involvement

Helen, King Zvonimir's widow, tried to keep power in Croatia. Some Croatian nobles asked King Ladislaus I of Hungary for help. They offered him the Croatian throne, believing he had a right to it through his sister Helen. In 1091, Ladislaus crossed the Drava river and took control of Slavonia without much resistance. However, his advance was stopped near Mount Gvozd.

Ladislaus had to return to Hungary because of an attack by the Cumans. He appointed his nephew, Prince Álmos, to rule the Croatian areas he controlled. He also established the Diocese of Zagreb.

King Petar Svačić

While the war continued, Petar Svačić was chosen as king by Croatian nobles in 1093. His base was in Knin. Petar fought against Álmos, who eventually had to withdraw to Hungary.

Ladislaus died in 1095. His nephew, Coloman, continued the campaign. Coloman gathered a large army. In 1097, he defeated King Petar's troops in the Battle of Gvozd Mountain, where Petar was killed.

Since Croatia no longer had a leader, negotiations began between Coloman and the Croatian nobles. It took several years for the Croatian nobility to accept Coloman as their king. Coloman was crowned in Biograd in 1102. He claimed the title "King of Hungary, Dalmatia, and Croatia."

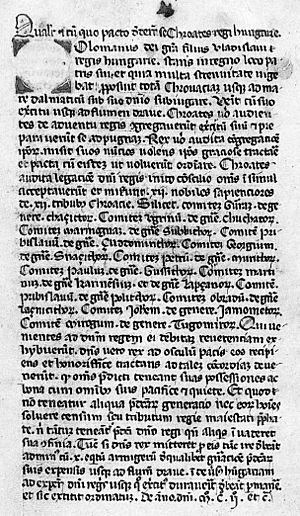

The Pacta Conventa

The terms of his coronation are summarized in a document called Pacta Conventa. In this agreement, Croatian nobles recognized Coloman as king. In return, the 12 Croatian nobles who signed the agreement kept their lands and were free from taxes. They also agreed to send armed horsemen to help the king if his borders were attacked. While the Pacta Conventa itself might not be an original document from 1102, historians believe there was a similar agreement that set out these terms.

Union with Hungary

In 1102, after the succession crisis, the crown of Croatia passed to the Árpád dynasty of Hungary. King Coloman of Hungary was crowned "King of Croatia and Dalmatia" in Biograd.

The Nature of the Union

The exact terms of this union were debated for a long time. Croatian historians believe it was a personal union. This means Croatia and Hungary were separate kingdoms that simply shared the same king. Many Hungarian historians now agree with this view. Some earlier historians saw it as Hungary taking over Croatia. However, today it is generally accepted that Coloman was crowned as king in Biograd.

Historians describe the relationship between Hungary and Croatia until 1526 as similar to a personal union. Croatia kept its own local governor, called a Ban. It also had its own powerful nobles and an assembly of nobles called the Sabor. Hungarian culture influenced northern Croatia, and the border between the two often changed.

Croatia kept a lot of its internal independence. The level of Croatian self-rule changed over the centuries, as did its borders.

Consequences of the Union

Croatia joining a personal union with Hungary had important effects. Separate Croatian state institutions continued to exist. The Sabor (parliament) and the Ban (viceroy) continued to govern in the king's name. The Croatian nobles kept their lands and titles. Coloman also kept the Sabor and removed taxes on Croatian land.

Coloman's successors continued to be crowned separately as Kings of Croatia in Biograd na Moru for some time. In the 14th century, a new term, Archiregnum Hungaricum (Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen), was used to describe the collection of independent states under the Hungarian King. Croatia remained a distinct crown linked to Hungary until the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Reino de Croacia para niños

In Spanish: Reino de Croacia para niños

- Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg)

- Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

- History of Croatia

- Pacta conventa (Croatia)

- Crown of Zvonimir

- Bans of Croatia

- Timeline of Croatian history

- List of rulers of Croatia