History of Croatia facts for kids

The land we know today as Croatia was once part of the Roman Empire. After the Western Roman Empire fell apart in the 5th century, the area was ruled by the Ostrogoths for 50 years. Then, it became part of the Byzantine Empire.

Croatia first appeared as a small state called a duchy in the 7th century. It was known as the Duchy of Croatia. This duchy later joined with another nearby area and became the Kingdom of Croatia. This kingdom lasted from 925 to 1102. From the 12th century, the Kingdom of Croatia joined with the Kingdom of Hungary in a special agreement called a personal union. Croatia remained a separate state with its own ruler, called a Ban, and its own parliament, the Sabor. However, it chose its kings from powerful families in nearby countries, mainly Hungary, Naples, and the Habsburg monarchy.

From the 15th to the 17th centuries, Croatia faced big challenges. There were many fights between the Ottoman Empire from the south and the Habsburg Empire from the north.

After World War I ended in 1918, Croatia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In April 1941, during World War II, Germany invaded Yugoslavia. A new state, the Independent State of Croatia, was set up. It was allied with the Axis powers. This state was defeated in May 1945. After that, the Socialist Republic of Croatia was formed. It was one of the republics within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In 1991, Croatia decided to leave Yugoslavia and declared its independence. This happened as Yugoslavia was breaking up.

Contents

- Ancient Times in Croatia

- Roman Control of Croatia

- Duchy of Croatia (800–925)

- Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102)

- Personal Union with Hungary (1102–1527)

- Croatia in the Habsburg Monarchy (1527–1918)

- Croats in the First Yugoslavia (1918–1941)

- World War II and the Independent State of Croatia (1941–1945)

- Socialist Yugoslavia (1945–1991)

- Republic of Croatia (1991–Present)

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Times in Croatia

The land that is now Croatia has been home to people for a very long time. Scientists have found bones of Neanderthals in northern Croatia. These bones are from the Middle Stone Age. The most famous place where these bones were found is Krapina.

Many signs of early farming cultures have also been found across the country. Most of these ancient sites are in the river valleys of northern Croatia. Important cultures like the Starčevo, Vučedol, and Baden culture lived here. During the Iron Age, people from the early Illyrian Hallstatt culture and the Celtic La Tène culture also lived in this area.

Early History: Greek Settlers

Around 500 BC, a Greek writer named Hecataeus of Miletus wrote about the eastern Adriatic region. He said that groups like the Histrians, Liburnians, and Illyrians lived there. Later, Greek settlers came and built communities on islands like Issa (Vis) and Pharos (Hvar).

Roman Control of Croatia

Before the Romans arrived, the eastern Adriatic coast was the northern part of the Illyrian kingdom. This kingdom existed from the 4th century BC until the Illyrian Wars in the 220s BC. In 168 BC, the Roman Republic took control of the area south of the Neretva river. The land north of the Neretva slowly became Roman territory. The Roman province of Illyricum was officially created around 32–27 BC.

These lands then became part of the Roman province of Illyricum. Between 6 and 9 AD, local tribes, including the Dalmatae, rebelled against the Romans. This was called the Great Illyrian revolt. But the Romans crushed the uprising. In 10 AD, Illyricum was split into two provinces: Pannonia and Dalmatia. The province of Dalmatia stretched inland, covering most of the Dinaric Alps and the eastern Adriatic coast.

Diocletian, a Roman Emperor, was born in Dalmatia. When he retired in 305 AD, he built a huge palace near Salona. The city of Split later grew around this palace.

Some historians believe that by the 4th century, everyone in Dalmatia spoke Latin and followed Roman ways. Others argue that Roman culture mostly spread in cities, but not so much in the countryside. In the countryside, older Illyrian ways of life continued.

After the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 AD, the region was ruled by the Ostrogoths. Then, in 535 AD, Justinian I added the territory to the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines later created a region called the Theme of Dalmatia in the same area.

The Migration Period

The Roman period ended with invasions by the Avars and Croats in the 6th and 7th centuries. Almost all Roman towns were destroyed. Roman survivors moved to safer places on the coast, islands, and mountains. For example, the city of Ragusa was founded by people who escaped from Epidaurum.

According to a book written by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII in the 10th century, the Croats came to what is now Croatia from southern Poland and Western Ukraine in the early 7th century. However, this idea is debated. Some believe it happened in the late 6th or early 7th century, while others suggest the late 8th or early 9th century. Recent discoveries show that the Slavs/Croats migrated and settled in the late 6th and early 7th centuries.

Duchy of Croatia (800–925)

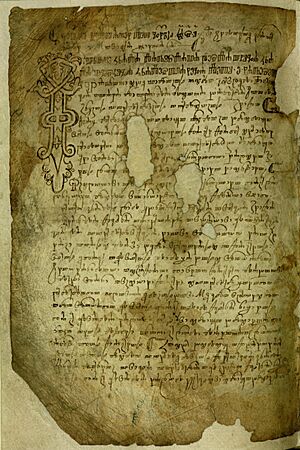

From the mid-7th century until 925, there were two main duchies in the area of modern Croatia. These were the Duchy of Croatia and the Principality of Lower Pannonia. Eventually, the Duchy of Croatia was formed. It was ruled by Borna, as mentioned in old records from 818. These records show the first Croatian states, which were under the rule of Francia at the time.

The most important ruler of Lower Pannonia was Ljudevit Posavski. He fought against the Franks from 819 to 823. He ruled Pannonian Croatia from 810 to 823.

Frankish rule ended during the time of Duke Mislav. Duke Mislav was followed by Duke Trpimir, who started the Trpimirović dynasty. Trpimir successfully fought against the Byzantines, Venice, and Bulgaria. After him came Duke Domagoj, who often fought against the Venetians and Byzantines. The Venetians even called him "the worst Croatian prince."

The Christianization of Croats is often linked to the 9th century. In 879, under Branimir, the Duke of Croatia, Dalmatian Croatia was officially recognized as a state by Pope John VIII.

Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102)

The first king of Croatia is generally believed to be Tomislav. He ruled in the first half of the 10th century. He is mentioned as king in records from Church Councils in Split and in a letter from Pope John X.

Other important Croatian rulers from this time include:

- Mihajlo Krešimir II (949-969): He conquered Bosnia and made the Croatian kingdom powerful again.

- Stjepan Držislav (969-997): He was an ally of Byzantium in a war against the Bulgarian emperor Samuil.

- Stjepan (1030-1058): He brought back the strength of the Croatian kingdom and started a diocese (church area) in Knin.

Two Croatian queens are also known from this century: Domaslava and Helen of Zadar. Helen's tombstone was found in the Solin area in the late 19th century.

The medieval Croatian kingdom was strongest in the 11th century. This was during the reigns of Petar Krešimir IV (1058–1074) and Demetrius Zvonimir (1075–1089). When Stjepan II died in 1091, the Trpimirović family line ended. Ladislaus I of Hungary then claimed the Croatian crown. He said he had a right to it because Zvonimir's wife, Jelena (Helen), was the daughter of Hungarian king Béla I.

People who opposed this claim led to a war. One army was loyal to Petar Sančić, and the other to the Hungarian king Koloman I. After Petar Sančić's army was defeated, Croatia and Hungary formed a personal union in 1102. Coloman became the ruler of both.

Personal Union with Hungary (1102–1527)

Croatia under the Árpád Dynasty

When Croatia joined in a personal union with Hungary, a new system called feudalism was introduced. This meant that land was given to nobles in exchange for loyalty and military service. Over the next four centuries, the Kingdom of Croatia was managed by its own parliament, the Sabor, and a Ban (a viceroy) chosen by the king.

In 1217, Hungarian king Andrew II went on the Fifth Crusade. He traveled through Croatia to reach the Holy Land. Later, King Béla IV had to deal with the first Mongol invasion of Hungary. After a big defeat in 1241, the king fled to Dalmatia to find safety. The Mongols chased him but eventually left when they heard their leader, Ögedei Khan, had died. During Béla's time in Dalmatia, the noble Šubić family helped him. In return, the king gave them the County of Bribir. This is where their power became very strong under Paul I Šubić of Bribir.

This period saw the rise of powerful Croatian noble families like the Frankopans and the Šubićs. Many future Bans of Croatia came from these families. The princes of Bribir from the Šubić family became especially important. They controlled large parts of Dalmatia, Slavonia, and even Bosnia.

Croatia under the Anjou Dynasty

Lord Paul Šubić became so powerful that he ruled almost like an independent king. He even made his own money and held the title of Ban of Croatia as a family right. When King Ladislaus IV of Hungary died without a son, there was a crisis over who would be the next king. In 1300, Paul invited Charles Robert of Anjou to become the new king of Hungary. This led to a civil war, which Charles's side won in 1312.

Over time, the custom of separately crowning kings of Croatia stopped. Charles Robert was the last to be crowned King of Croatia in 1301. After that, Croatia had its own separate laws. Lord Paul Šubić died in 1312, and his son Mladen became the Ban of Croatia. However, Mladen's power was reduced by the new king's efforts to centralize power. Mladen and his forces were defeated in 1322.

The fall of Mladen Šubić created a power vacuum. Venice used this chance to regain control over many cities in Dalmatia.

The reign of King Louis the Great (1342–1382) is seen as a golden age for medieval Croatian history. Louis launched a war against Venice to take back the Dalmatian cities. He succeeded, forcing Venice to sign the Treaty of Zadar in 1358. This peace treaty also led to the Republic of Ragusa becoming independent from Venice.

Struggles Against the King

After King Louis the Great died in 1382, Hungary and Croatia entered a period of civil war. This was called the Anti-Court movement. Two groups fought for power. One supported Louis's daughter, Mary, her mother Queen Elizabeth, and Mary's fiancé Sigismund of Luxemburg. The other group was made up of Croatian nobles who wanted Charles of Durazzo to be the new king. They didn't want to be ruled by a woman or by Sigismund, whom they saw as a foreigner.

They arranged for Charles of Durazzo to come to Croatia. He was crowned the new king of Hungary-Croatia in December 1385. In response, Queen Elizabeth and Princess Mary had Charles assassinated in February 1386. The angry anti-court supporters then ambushed the two queens in July 1386. Their guards were killed, and both queens were taken prisoner to Novigrad Castle near Zadar. Queen Elizabeth was killed there, but Mary was eventually rescued by Sigismund.

In 1387, Sigismund of Luxemburg crowned himself the new king of Hungary-Croatia. He continued to fight against opposing Croatian and Bosnian nobles to secure his rule. In 1396, Sigismund led a crusade against the growing Ottoman Empire. This ended in the Battle of Nicopolis. After the battle, it was unclear if Sigismund was alive. So, some nobles declared Ladislaus of Naples the new king.

When Sigismund returned to Croatia, he called a meeting in Križevci in 1397. There, he confronted and eliminated his enemies. Sigismund had to fight for control again. By 1403, all of southern Croatia and the Dalmatian cities had switched their loyalty to Ladislaus of Naples. Sigismund finally crushed the anti-court movement by winning a battle in Bosnia in 1408.

Since Ladislaus had lost hope of winning against Sigismund, he sold all his claims in Dalmatia to the Republic of Venice for 100,000 ducats in 1409. The Venetians took control of most of Dalmatia by 1428. Venice ruled most of Dalmatia for nearly four centuries (around 1420–1797).

Another long-term result of these struggles was the arrival of the Ottomans. A powerful Bosnian duke invited them to help him fight against King Sigismund. The Ottomans slowly gained influence in Bosnia and finally conquered the kingdom in 1463.

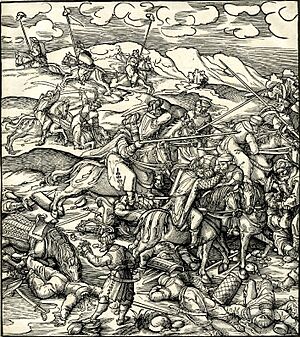

Ottoman Expansion

Serious attacks by the Ottoman Empire on Croatian lands began after Bosnia fell to the Ottomans in 1463. At this time, the Ottomans were not yet focused on Central Europe, but on Italy. Croatia was in their way. As the Ottomans expanded further into Europe, Croatian lands became a constant battlefield. This period is considered one of the hardest times for people living in Croatia. A poet from that time described it as "two centuries of weeping Croatia."

Croatian noble armies fought many battles to stop Ottoman raids. Ottoman forces often attacked the Croatian countryside, stealing from towns and villages and taking people as slaves. These "scorched earth" tactics, also called "The Small War," were usually done once a year. They aimed to weaken the region's defenses but didn't always lead to actual conquest.

And after conquering Greece and Bulgaria, Bosnia and Albania, [Turks] flocked onto people of Croatia by sending many armies. Many warlords started frequent battles with Christian people fighting on the fields and in mountain passes and on river fords. That's when all Croatian and Slavic lands were enslaved all the way to Sava river and Drava and even Mons Claudius, all settlements of Carniola all the way to sea, by enslaving, robbing, burning houses of Lord and crushing Lord's altars. They attacked old people using weapons, young women [...] widows and even squealing children; not only that they took people of God in violent sorrow, shackled in chains, but they also sold people on markets like it is accustomed to do with the cattle.

After King Mathias Corvinus died in 1490, a war started over who would be the next king. Supporters of Vladislaus Jagiellon won over those of Maximilian Habsburg. Maximilian had many supporters among Croatian nobles. A good peace treaty he made with Vladislaus allowed Croatians to increasingly turn to the Habsburgs for protection from Ottoman attacks. Their own king, Vladislaus, couldn't provide much help. In the same year, Croatian nobles also refused to recognize Vladislaus II as ruler until he promised to respect their freedoms. They insisted he remove certain phrases from the laws that seemed to make Croatia just a province. This disagreement was settled in 1492.

Meanwhile, constant Ottoman attacks, along with famines, diseases, and cold weather, caused many people to leave. People fled to safer areas. A Croatian historian points out that Croatia "lost almost three-fifths of its population" and its territory became less connected. Because of this, the center of the Croatian medieval state slowly moved north into western Slavonia (Zagreb). Frequent Ottoman raids led to the 1493 Battle of Krbava field, which ended in a Croatian defeat.

Croatia in the Habsburg Monarchy (1527–1918)

The "Remnants of the Remnants"

Croats fought many battles but lost more and more land to the Ottoman Empire. Eventually, Croatia was reduced to a small area. This is often called the "Remains of the Remains of Once Glorious Croatian Kingdom." A very important battle between the Hungarian army and the Ottomans occurred on Mohács in 1526. The Hungarian king Louis II was killed, and his army was destroyed.

Because of this, in November 1526, the Hungarian parliament chose János Szapolyai as the new king of Hungary. In December 1526, another Hungarian parliament chose Ferdinand I of the House of Habsburg as King of Hungary.

The Croatian nobles met in Cetingrad in 1527. They chose Ferdinand I of the Habsburg family as the new ruler of Croatia. They had two conditions: he had to help defend Croatia against the Ottomans, and he had to respect Croatia's political rights. The parliament of Slavonia, however, chose Szapolyai. A civil war started between the two kings. But later, the Habsburgs won, and both crowns were united. The Ottoman Empire used these problems to expand in the 16th century. They took most of Slavonia, western Bosnia (then called Turkish Croatia), and Lika. These areas became part of the Ottoman Empire.

Later in the same century, Croatia was so weak that its parliament allowed Ferdinand Habsburg to take large parts of Croatia and Slavonia. These areas were next to the Ottoman Empire. They were used to create the Military Frontier. This was a buffer zone against the Ottomans, managed directly by Austria. This area became empty due to constant fighting. It was later settled by Serbs, Vlachs, Croats, and Germans.

People living in the Military Frontier had to serve in the army for the Habsburg Empire. Because of this, they were free from serfdom (a type of forced labor) and had more political freedom. This was different from the people living in areas managed by the Croatian Ban and Sabor. This was officially confirmed by a decree in 1630 called Statuta Valachorum.

Hasan Pasha's Big Attack on Croatia

In the 1590s, a fierce leader named Telli Hasan Pasha became the new governor of the Ottoman Bosnian region. He launched a huge attack on Croatia. His goal was to completely conquer the remaining Croatian lands. He gathered all available troops from his Bosnian region.

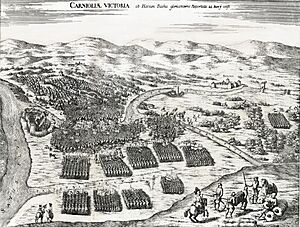

His attack had some success against the Croatians and their allies. For example, he won the Siege of Bihać (which Croatians never took back) and the Battle of Brest. However, his campaign was finally stopped in the Battle of Sisak in June 1593. Not only did the Ottomans lose this battle, but Hasan Pasha himself was killed.

News of this defeat made the Ottoman leaders in Constantinople very angry. They officially declared war on the Habsburg Monarchy, starting the Long Turkish War. In a strategic sense, the Ottoman defeat near Sisak helped stabilize the border between Croatia and the Ottoman Empire. Historians say that this border remained mostly stable in the 17th century as the Ottoman Empire's power began to decline.

Zrinski-Frankopan Conspiracy

In the 17th century, a famous Croatian noble named Nikola Zrinski became a leading general in the fight against the Ottomans. In 1663/1664, he led a successful attack into Ottoman territory. This attack destroyed the important Osijek bridge, which connected the Pannonian plain with the Balkan lands. For his victory, Zrinski was praised by the French king Louis XIV. This helped him connect with the French court. Croatian nobles also built Novi Zrin castle to protect Croatia and Hungary from further Ottoman attacks.

At the same time, Emperor Leopold of Habsburg wanted to have complete control over all Habsburg lands. This meant the Croatian parliament and Ban would lose their power. This made many Croats unhappy with Habsburg rule.

In July 1664, a large Ottoman army attacked and destroyed Novi Zrin. As this army marched into Austrian lands, it was defeated in the Battle of St. Gotthard by the Habsburg imperial army. Croatians expected the Habsburgs to launch a big counter-attack to push the Ottomans back. But Leopold decided to sign an unfavorable peace treaty with the Ottomans, called the Vasvar peace treaty. He did this because he had problems with the French on the Rhine at the time.

In Croatia, this decision angered leading nobles. It led to a secret plan to replace the Habsburgs with different rulers. After Nikola Zrinski died in strange circumstances while hunting, his relatives Fran Krsto Frankopan and Petar Zrinski supported the plan.

The plotters contacted the French, Venetians, Poles, and even the Ottomans. But Habsburg spies at the Ottoman court discovered their plan. The plotters were invited to make peace with the emperor, which they agreed to. However, when they arrived in Austria, they were accused of treason and sentenced to death. They were executed in Wiener Neustadt in April 1671. Their families, who had been important in Croatian history for centuries, were then destroyed by the imperial authorities. All their property was taken away.

Great Turkish War: Croatia Reborn

Even though the Ottoman Empire was getting weaker in the 17th century, the Ottoman leaders decided to attack the Habsburg capital of Vienna in 1683. Their attack was a disaster, and the Ottomans were defeated near Vienna by Christian armies. Soon after, the Holy League was formed, and the Great Turkish War began.

In Croatia, several commanders became famous. Friar Luka Ibrišimović led rebels who defeated the Ottomans in Požega. Marko Mesić led an uprising against the Ottomans in Lika. Hajduk leader Stojan Janković led troops in Dalmatia. Croatian Ban Nikola (Miklos) Erdody led his troops in the Siege of Virovitica, which was freed from the Ottomans in 1684. Osijek was freed by 1687, Kostajnica by 1688, and Slavonski Brod by 1691. An attempt to retake Bihać in 1697 was called off because there weren't enough cannons.

In the same year, General Eugene of Savoy led an army from Osijek into Bosnia. He attacked the capital of the Bosnia Eyalet, Sarajevo, and burned it down. After this attack, many Christian refugees from Bosnia settled in Slavonia, which was almost empty then.

After the Ottomans were decisively defeated in the Battle of Zenta in 1697, the Peace of Karlowitz was signed in 1699. This treaty confirmed that all of Slavonia was freed from the Ottomans. However, Croatia lost large parts of its medieval territories between the rivers Una and Vrbas. These areas remained part of the Ottoman Bosnia Eyalet. In the following years, the German language became more common in the new military borderland. German-speaking settlers moved into these areas over the next two centuries.

Enlightened Rulers

By the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire had been pushed out of Hungary. Austria brought its empire under central control. Since Emperor Charles VI had no sons, he wanted his daughter Maria Theresa of Austria to inherit the throne. This led to the War of Austrian Succession from 1741–1748. The Croatian Parliament agreed to accept Maria Theresa as a ruler. In return, they asked that whoever inherited the throne would recognize and respect Croatia's independence from Hungary. The king reluctantly agreed.

Maria Theresa's rule brought some modern changes in education and healthcare. The Croatian Royal Council was founded in Varaždin in 1767. It acted as the Croatian government. However, it was abolished in 1779, and its power was given to Hungary. The founding of the Croatian Royal Council in Varaždin made this town the administrative capital of Croatia. But a big fire in 1776 badly damaged the city, so these important Croatian government offices moved to Zagreb.

Maria Theresa's son, Joseph II of Austria, also ruled as an enlightened absolute monarch. But his changes aimed to centralize power and spread German culture. During this time, roads were built connecting Karlovac with Rijeka, and the Jozefina road connecting Karlovac with Senj. The Treaty of Sistova, which ended the Austro-Turkish War (1788-1791), gave Ottoman-held areas like Donji Lapac and Cetingrad to the Habsburg monarchy. These were added to the Croatian Military Frontier.

19th Century in Croatia

Napoleonic Wars

As Napoleon's armies took control of Europe, Croatian lands also came into contact with the French. When Napoleon ended the Republic of Venice in 1797, the former Venetian territories in Dalmatia came under Habsburg rule. In 1809, after Napoleon defeated the Austrians, French-controlled territory expanded to the Sava river.

The French created the "Illyrian Provinces" with their center in Ljubljana. Marshal Auguste de Marmont was appointed their governor-general. The French brought new ideas from the French Revolution to the Croats, like freedom and equality. The French built roads and printed the first newspapers in the local language in Dalmatia. One newspaper, Kraglski Datmatin/Il Regio Dalmata, was printed in both Italian and Croatian. Croatian soldiers even fought with Napoleon in Russia. In 1808, Napoleon abolished the Republic of Ragusa.

Ottoman forces from Bosnia raided French Croatia and took control of the Cetingrad area in 1809. Auguste de Marmont responded by occupying Bihać in May 1810. After the Ottomans promised to stop raiding French territories and leave Cetingrad, he withdrew from Bihać. With Napoleon's fall, the French-controlled Croatian lands returned to Austrian rule.

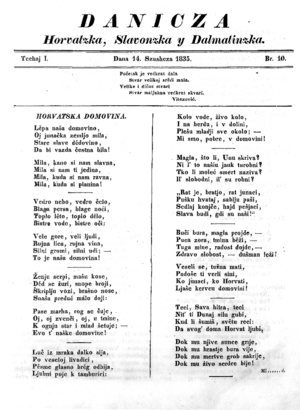

Croatian National Revival

In the mid-19th century, a movement called the Croatian National Revival began. It was influenced by German ideas, French political thought, and pan-Slavism (the idea of unity among Slavic peoples). This movement aimed to stop the spread of German and Hungarian culture in Croatia.

Ljudevit Gaj became a leader of this movement. A key goal was to standardize the Croatian language. Since the Shtokavian dialect was common among Croats and Serbs, this movement also had a South-Slavic feel. At the time, "Croatian" referred only to people in certain parts of Croatia. The term "Illyrian" was used to attract more people across the South-Slavic world. Illyrian activists chose the Shtokavian dialect as the standard Croatian language. However, the Illyrian movement was not fully accepted by Serbs or Slovenes, and it remained mainly a Croatian national movement.

In 1832, Croatian count Janko Drašković wrote an important text called Disertacija (Dissertation). This text called for uniting Croatia with Slavonia, Dalmatia, Rijeka, the Military Frontier, Bosnia, and Slovene lands into one unit within the Hungarian part of the Austrian Empire. This new unit would have Croatian as its official language and be governed by a Ban. The movement spread throughout Dalmatia, Istria, and among Bosnian Franciscan monks. It led to the creation of the modern Croatian nation and the first Croatian political parties. After the name "Illyrian" was banned in 1843, its supporters changed their name to "Croatian."

On May 2, 1843, Ivan Kukuljević Sakcinski gave the first speech in the Croatian language in the Croatian Sabor (parliament). He asked for Croatian to become the official language in public offices. This was a big step because Latin was still used in public institutions in Croatia. In 1847, the Sabor officially declared Croatian as the official language in Croatia.

Croats in the 1848 Revolutions

In the Revolutions of 1848, the Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia supported the Habsburg rulers. They did this because they feared Hungarian nationalism.

During a meeting of the Croatian Sabor on March 25, 1848, Colonel Josip Jelačić was chosen as Ban of Croatia. A petition called "Demands of The People" was written to be given to the Austrian Emperor. These demands asked for:

- Independence for Croatia.

- Unification of all Croatian lands.

- A Croatian government responsible to the Croatian parliament, independent from Hungary.

- Financial independence from Hungary.

- Croatian language in offices and schools.

- Freedom of the press and religious freedom.

- End of serfdom and noble privileges.

- Creation of a people's army.

- Equality before the law.

The Hungarian government refused to recognize the Croatian name and nation. It treated Croatian institutions as if they were just local offices. So, Jelačić cut ties between Croatia and Hungary. In May 1848, the Ban's Council was formed. It had all the executive powers of the Croatian government. The Croatian parliament ended feudalism and serfdom. It also demanded that the Monarchy become a federal state of equal nations. This state would have independent national governments and one federal parliament in Vienna. The Croatian parliament also asked for the unification of the Military Frontier and Dalmatia with Croatia proper. It also wanted an alliance with Istria, Slovene lands, and parts of southern Hungary where Croats and Serbs lived.

Jelačić was also made governor of Rijeka and Dalmatia. He was also the "Imperial Commander of Military Frontier." This meant he controlled most of the Croatian lands. Talks between Croats and Hungarians failed, leading to war. Jelačić declared war on Hungary on September 7, 1848. On September 11, 1848, the Croatian army crossed the Drava river and took Međimurje. When crossing the Drava, Jelačić ordered his army to switch Croatian flags with Habsburg Imperial flags.

Even though Ban Josip Jelačić helped put down the Hungarian war of independence, Croatia was not treated much better by Vienna than the Hungarians. Croatia lost its internal independence.

Croatia in the Dual Monarchy

The dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary was created in 1867. Croatian independence was restored in 1868 with the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement. This agreement was quite good for Croatians, but it still had problems. For example, the status of Rijeka was not resolved. In 1873, the Military Frontier was demilitarized. In July 1871, it was decided to include it into Croatia. Croatian Ban Ladislav Pejačević took over its authority.

Pejačević's successor, Károly Khuen-Héderváry, caused more problems. He violated the Croatian-Hungarian Settlement with his strong policies to make Croatia more Hungarian. This happened from 1883 to 1903. Héderváry's policies led to big riots in 1903. Croatian protesters burned Hungarian flags and fought with police and soldiers. Several protesters died. As a result, Héderváry left his position as Ban of Croatia, but he was appointed prime minister of Hungary.

A year earlier, in 1902, the Srbobran newspaper in Zagreb published an article. The article denied the existence of the Croatian nation and language. It announced Serbian victory over "servile Croats," who, it claimed, would be wiped out. This article caused major anti-Serb riots in Zagreb. Barricades were put up, and Serb-owned properties were attacked. Serbs in Zagreb later distanced themselves from the article's opinions.

World War I ended the Dual Monarchy. Croatia suffered many losses in World War I. Towards the end of the war, there were ideas to change the monarchy into a federal one. This would include a separate Croatian/South Slavic section. However, these plans were never carried out. This was partly because Woodrow Wilson announced a policy of self-determination for the peoples of Austria-Hungary.

Shortly before the war ended in 1918, the Croatian Parliament cut ties with Austria-Hungary. This happened after they heard that the Czechoslovak parts had also separated. The Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia became part of the new provisional State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. This state was not recognized internationally. It included all South Slavic territories of the old Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Its temporary government was in Zagreb.

Its biggest problem was the advancing Italian army. Italy wanted to take the Croatian Adriatic territories that were promised to them by the Treaty of London in 1915. A solution was sought by uniting with the Kingdom of Serbia. Serbia had an army that could fight the Italians. It also had international support among the members of the Entente Cordiale. These countries were about to redraw European borders at the Paris Peace Conference.

Croats in the First Yugoslavia (1918–1941)

A new state was formed in late 1918. Srijem left Croatia-Slavonia and joined Serbia. This was soon followed by a vote for Bosnia and Herzegovina to join Serbia. The People's Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs decided to merge with the Kingdom of Serbia. This decision was made without the approval of the Croatian Sabor.

An Italian army eventually took Istria. It began to annex the Adriatic islands one by one and even landed in Zadar. A partial solution to the Adriatic Question came in 1920 with the Treaty of Rapallo.

The Kingdom changed significantly in 1921, to the dismay of Croatia's largest political party, the Croatian Peasant Party. The new constitution got rid of historical regions, including Croatia and Slavonia. It centralized power in the capital, Belgrade. The Croatian Peasant Party boycotted the government, except for a short time between 1925 and 1927. This was when Italy and its allies threatened Yugoslavia.

Two different ideas about how the new state should be run became the main source of conflict. Croatian leaders wanted a federal state where Croats would have some independence. Serbian-centered parties wanted a centralized state with one strong government. The new country's military was also mostly Serbian. By 1938, only about 10% of all army officers were Croats. The new school system focused on Serbian culture. Croatian teachers were often retired, removed, or moved to other places. Serbs were also appointed to high government positions. The old money was exchanged at an unfair rate.

In the early 1920s, the Yugoslav government used police pressure, seized opposition pamphlets, and rigged elections. This kept the opposition, mainly the Croatian Peasant Party, in the minority in parliament. The prime minister believed that Yugoslavia should be as centralized as possible. He wanted to create a "Greater Serbia" with power concentrated in Belgrade.

Murders and Royal Dictatorship

During a Parliament session in 1928, a Serbian deputy shot at Croatian deputies. This resulted in the killing of two Croatian politicians and the wounding of others. Stjepan Radić, a very important Croatian political leader, was wounded and later died from his injuries. This caused great anger among the Croatian people. It led to violent protests, strikes, and armed conflicts across Croatian parts of the country. The shooter was tried but served his sentence in a luxurious villa.

In response to the shooting, King Aleksandar ended the parliamentary system and declared a personal dictatorship. He introduced a new constitution that aimed to remove all existing national identities and create a single "Yugoslav" identity. He also renamed the country from the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Croatia's territory was largely divided into two new regions. Political parties were banned, and the royal dictatorship became very harsh. Vladko Maček, who took over as leader of the Croatian Peasant Party, was imprisoned.

This new situation inspired Ante Pavelić to leave Yugoslavia and create the Ustaše Movement. Their ultimate goal was to destroy Yugoslavia and make Croatia an independent country. In 1931, the royal regime organized the assassination of Croatian scientist Milan Šufflay in Zagreb. This assassination was condemned by famous thinkers like Albert Einstein. In 1932, the Ustaše Movement tried to start an uprising in Lika, but it failed. Despite the harsh rule, the Ustaše movement never gained strong support among the Croatian people.

Banovina of Croatia

In 1934, King Aleksandar was assassinated during a visit to Marseille. This was done by a group of Ustaše and Bulgarian revolutionaries. This ended the Royal dictatorship. The government that took power in 1935 moved Yugoslavia closer to Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.

With the rise of Nazis in Germany and the possibility of another European war, Serbian political leaders decided it was time to improve relations with the Croats. They wanted the country to be united in case of a new war. Negotiations began, leading to the Cvetković–Maček Agreement and the creation of Banovina of Croatia. This was an independent Croatian province within Yugoslavia.

Banovina of Croatia was created in 1939. It included parts of Bosnia, most of Herzegovina, and the city of Dubrovnik and its surroundings. It had a rebuilt Croatian Parliament that would choose a Croatian Ban and Viceban.

World War II and the Independent State of Croatia (1941–1945)

When the Axis occupation of Yugoslavia happened in 1941, the Croatian far-right Ustaše group came to power. They formed the "Independent State of Croatia" (NDH), led by Ante Pavelić. Following the example of other fascist governments in Europe, the Ustaše passed laws against certain groups. They set up eight concentration camps targeting Serbs, Roma, and Jewish people, as well as Croats and Bosnian Muslims who opposed the regime. The largest concentration camp was Jasenovac in Croatia. The NDH had a plan to remove Serbs from Croatia, and about 330,000 Serbs were killed.

Various Serbian nationalist groups also committed terrible acts against Croats in areas like Lika and parts of northern Dalmatia. During World War II in Yugoslavia, these groups killed an estimated 18,000-32,000 Croats.

The anti-fascist communist-led Partisan movement started in early 1941. It was led by Josip Broz Tito, who was born in Croatia. This movement quickly spread across Yugoslavia. The 1st Sisak Partisan Detachment, often seen as the first armed anti-fascist resistance group in occupied Europe, was formed in Croatia. As the movement grew, Partisans gained strength from Croats, Bosniaks, Serbs, Slovenes, and Macedonians who wanted a united, but federal, Yugoslav state.

By 1943, the Partisan resistance movement was winning. In 1945, with help from the Soviet Red Army, they drove out the Axis forces and their local supporters. The State Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Croatia (ZAVNOH) had been working since 1942. By 1943, it formed a temporary civil government.

After the Independent State of Croatia was defeated at the end of the war, many Ustaše, civilians who supported them, and anti-Communists tried to flee to Austria. They hoped to surrender to British forces and find safety. However, after the Bleiburg repatriations, they were instead held by British forces and returned to the Partisans. There, many were executed.

Socialist Yugoslavia (1945–1991)

Tito's Leadership (1945–1980)

Croatia was one of six socialist republics in the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia. Under the new communist system, private factories and lands were taken over by the state. The economy was based on a type of planned market socialism. The country rebuilt after World War II, became more industrialized, and started developing tourism.

The socialist system provided free apartments from large companies. These companies, with worker investments, paid for living spaces. From 1963, Yugoslav citizens could travel to almost any country because of its neutral politics. No visas were needed for Eastern or Western countries. This was very unusual at the time, especially compared to countries in the Eastern Bloc. This freedom helped Croatians who found better-paying jobs in foreign countries. Many planned to return to Croatia after retirement to buy property.

In Yugoslavia, people in Croatia had free healthcare, free dental care, and secure pensions. Older people found this comforting, as pensions sometimes exceeded their former paychecks. Free trade and travel within the country also helped Croatian industries. They imported and exported goods throughout all the former republics.

Students and military personnel were encouraged to visit other republics to learn about the country. All levels of education, including high school and college, were free. However, housing was often poor, medical care lacked basic supplies, and schools were used for propaganda. Travel was often a necessity for the country to earn foreign money. Free speech was limited, and citizens were not always protected from ethnic attacks.

Being a member of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia was often required for college admission and government jobs. Private businesses did not grow much because taxes on them were very high. Inexperienced managers sometimes made decisions that hurt productivity or profit. Strikes were forbidden.

The economy developed a system called samoupravljanje (self-management). In this system, workers controlled state-owned businesses. This type of market socialism created much better economic conditions than in Eastern Bloc countries. Croatia went through rapid industrialization in the 1960s and 1970s. Industrial output increased many times, and Zagreb surpassed Belgrade in industry. Factories and other organizations were often named after Partisans who were declared national heroes. This also happened with street names, parks, and buildings.

Before World War II, Croatia's industry was not developed. Most people worked in agriculture. By 1991, the country had completely changed into a modern industrialized state. At the same time, the Croatian Adriatic coast became a popular tourist spot. Coastal republics, especially Croatia, benefited greatly from this. Tourist numbers reached levels still not surpassed in modern Croatia. The government brought economic growth, high levels of social security, and a very low crime rate. The country fully recovered from WWII and achieved high economic growth.

The constitution of 1963 balanced power between Croats and Serbs. This helped fix the fact that Croats were again a minority. However, events after 1965 led to the Croatian Spring of 1970–71. During this time, students in Zagreb organized protests. They wanted more civil liberties and greater Croatian independence. The government stopped the protests and jailed the leaders. But this led to a new constitution in 1974, which gave more rights to the individual republics.

Croatian groups living outside Yugoslavia tried to cause trouble within Yugoslavia. For example, in June 1971, a group of 19 armed men tried to start a popular uprising against the "Serbo-communist" government in Belgrade, but they failed.

Until the Breakup of Yugoslavia (1980–1991)

In 1980, after Tito's death, economic, political, and religious problems began to grow. The federal government started to fall apart. The crisis in Kosovo and the rise of Slobodan Milošević in Serbia in 1986 caused a very negative reaction in Croatia and Slovenia. Politicians from both republics feared that Milošević's actions would threaten their independence.

As changes swept across Eastern Europe in the 1980s, the communist system was challenged. At the same time, Milošević's government began to slowly concentrate Yugoslav power in Serbia. Calls for free multi-party elections became louder.

In June 1989, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) was founded. It was led by Croatian nationalist Franjo Tuđman, a former Partisan fighter and general. At this time, Yugoslavia was still a one-party state. Open displays of Croatian nationalism were seen as dangerous. So, the new party was founded almost secretly. It was only on December 13, 1989, that the ruling League of Communists of Croatia agreed to allow opposition political parties and hold free elections in the spring of 1990.

On January 23, 1990, the Communist League of Yugoslavia voted to end its monopoly on political power. On the same day, it effectively stopped existing as a national party. This happened when the League of Communists of Slovenia walked out after Serbia's President Slobodan Milošević blocked all their reform proposals. This caused the League of Communists of Croatia to further distance themselves from the idea of a joint state.

Republic of Croatia (1991–Present)

New Political System

On April 22 and May 7, 1990, the first free multi-party elections were held in Croatia. Franjo Tuđman's Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) won with 42% of the votes. Ivica Račan's reformed communist Party of Democratic Change (SDP) won 26%. Croatia's election system allowed Tuđman to form the government quite easily. The HDZ wanted to make Croatia independent. This was against the wishes of some ethnic Serbs in Croatia and federal politicians in Belgrade. The very tense situation quickly grew worse between the two groups.

On July 25, 1990, a Serbian Assembly was set up in Srb, north of Knin. It was meant to represent the Serbian people in Croatia. This assembly declared "sovereignty and autonomy of the Serb people in Croatia." Their idea was that if Croatia could leave Yugoslavia, then Serbs could leave Croatia. Milan Babić, a dentist from Knin, was chosen as president. The rebel Croatian Serbs formed some armed groups led by Milan Martić, the police chief in Knin.

On August 17, 1990, the Serbs of Croatia started what became known as the Log Revolution. They put barricades of logs across roads in the south. This showed their desire to separate from Croatia. This effectively cut Croatia in two, separating the coastal region of Dalmatia from the rest of the country. The Croatian government sent special police teams in helicopters, but they were stopped by Yugoslav Air Force jets and forced to return to Zagreb.

The Croatian constitution was passed in December 1990. It listed Serbs as a minority group, along with other ethnic groups. On December 21, 1990, Babić's group announced the creation of a Serbian Autonomous Oblast of Krajina. Other Serb-majority communities in eastern Croatia said they would also join SAO Krajina. They stopped paying taxes to the Zagreb government.

On Easter Sunday, March 31, 1991, the first deadly clashes happened. Police from the Croatian Ministry of the Interior entered the Plitvice Lakes National Park to remove rebel Serb forces. Serb armed groups ambushed a bus carrying Croatian police. This led to a day-long gun battle. One Croat and one Serb policeman were killed. Twenty other people were injured, and twenty-nine Serb armed men and policemen were captured by Croatian forces. Among the prisoners was Goran Hadžić, who later became the President of the Republic of Serbian Krajina.

On May 2, 1991, the Croatian parliament voted to hold an independence referendum. On May 19, 1991, almost 80% of people voted. Of those, 93.24% voted for independence. Krajina boycotted the referendum. They had held their own referendum a week earlier, on May 12, 1991, in the areas they controlled. They voted to stay in Yugoslavia. The Croatian government did not recognize their referendum as valid.

On June 25, 1991, the Croatian Parliament declared independence from Yugoslavia. Slovenia declared independence on the same day.

War of Independence (1991–1995)

During the Croatian War of Independence, many civilians fled the areas of fighting. Hundreds of thousands of Croats moved away from the Bosnian and Serbian border areas. In many places, large groups of civilians were forced out by the Yugoslav National Army (JNA). This army was mostly made up of soldiers from Serbia and Montenegro, and irregular fighters from Serbia. This became known as ethnic cleansing.

The border city of Vukovar was under siege for three months during the Battle of Vukovar. Most of the city was destroyed, and most of the people were forced to flee. Serbian forces took the city on November 18, 1991, and the Vukovar massacre happened.

Later, the United Nations arranged ceasefires. The fighting groups mostly stayed in their positions. The Yugoslav People's Army left Croatia and went into Bosnia and Herzegovina. There, new tensions were growing, and the Bosnian War was about to start. During 1992 and 1993, Croatia also took in about 700,000 refugees from Bosnia, mostly Bosnian Muslims.

Armed conflict in Croatia continued on and off, mostly on a small scale, until 1995. In early August, Croatia launched Operation Storm. This attack quickly took back most of the territories from the Republic of Serbian Krajina authorities. This led to many Serbs leaving the area. Estimates of Serbs who fled range from 90,000 to 200,000.

Because of this operation, the Bosnian War ended a few months later with the Dayton Agreement. The remaining Serbian-controlled territories in eastern Slavonia were peacefully integrated into Croatia by 1998, under UN supervision. Most of the Serbs who fled from former Krajina did not return. This was due to fears of ethnic violence, discrimination, and problems getting their property back. The Croatian government has not yet fully created the conditions for their complete return. According to the United Nations, about 125,000 ethnic Serbs who fled the 1991–1995 conflict have returned to Croatia. About 55,000 of them have stayed permanently.

Since the End of the War

Croatia became a member of the Council of Europe in 1996. The years 1996 and 1997 were a time of recovery after the war and improving economic conditions. However, in 1998 and 1999, Croatia faced an economic downturn, leading to thousands of people losing their jobs.

The rest of the former Krajina, near the FR Yugoslavia, negotiated a peaceful return to Croatia. This was done through the Erdut Agreement. The area became a temporary protectorate of the UN. It was officially rejoined with Croatia by 1998.

Franjo Tuđman's government started to lose popularity. It was criticized for its involvement in questionable privatization deals in the early 1990s and for international isolation. The country had a small economic slowdown in 1998 and 1999.

Tuđman died in 1999. In the early 2000 parliamentary elections, the nationalist Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) government was replaced by a center-left group. Ivica Račan became prime minister. At the same time, presidential elections were held, and a moderate, Stjepan Mesić, won. The new government changed the constitution. It shifted the political system from a presidential system to a parliamentary system. This moved most of the president's executive powers to the parliament and the prime minister.

The new government also started several big building projects. These included state-sponsored housing, more efforts to help refugees return, and building the A1 highway. The country saw good economic growth during these years. The unemployment rate continued to rise until 2001, when it finally started to fall. Croatia became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2000. It began the process of joining the Accession of Croatia to the European Union in 2003.

In late 2003, new parliamentary elections were held. A reformed HDZ party won, led by Ivo Sanader, who became prime minister. Joining Europe was delayed by disagreements over sending army generals to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), including Ante Gotovina.

Sanader was reelected in the close 2007 parliamentary election. Other issues continued to slow down the EU negotiation process. Most notably, Slovenia's blockade of Croatia's EU accession in 2008–2009. In June 2009, Sanader suddenly resigned and named Jadranka Kosor in his place. Kosor introduced measures to deal with the economic crisis. She also started a campaign against corruption among public officials. In late 2009, Kosor signed an agreement with Borut Pahor, the prime minister of Slovenia. This allowed the EU accession process to continue.

In the Croatian presidential election, 2009–2010, Ivo Josipović won by a large margin. Sanader tried to rejoin HDZ in 2010 but was then removed. He was soon arrested on several corruption charges. In November 2012, a Croatian court sentenced former Prime Minister Ivo Sanader to 10 years in prison for taking bribes. Sanader argued that the case against him was politically motivated.

In 2011, the agreement to join the EU was finalized. This gave Croatia the green light to join.

The 2011 Croatian parliamentary election was held on December 4, 2011. The Kukuriku coalition won. After the election, a center-left government was formed, led by new prime minister Zoran Milanović.

After the Treaty of Accession 2011 was approved and the 2012 Croatian European Union membership referendum was successful, Croatia joined the EU on July 1, 2013.

In the 2014–15 Croatian presidential election, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović became the first female President of Croatia.

The 2015 Croatian parliamentary election resulted in a victory for the Patriotic Coalition. They formed a new government. However, a vote of no confidence brought down this government. After the 2016 Croatian parliamentary election, a new government was formed.

In January 2020, the former prime minister Zoran Milanović won the presidential election. He defeated the current president, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović. In March 2020, the Croatian capital Zagreb experienced a 5.3 magnitude earthquake. It caused significant damage to the city. In July 2020, the ruling center-right party won the parliamentary election. In December 2020, Banovina, a less developed region of Croatia, was hit by a 6.4 magnitude earthquake. Several people died, and the town of Petrinja was destroyed.

During two and a half years of the global COVID-19 pandemic, 16,103 Croatian citizens died from the disease. In March 2022, a Soviet-made Tu-141 drone crashed in Zagreb. This was most likely due to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. On July 26, 2022, Croatian authorities opened the Pelješac Bridge. This bridge connects the southernmost part of Croatia with the rest of the country. On January 1, 2023, Croatia became a member of both the Eurozone (using the Euro currency) and the Schengen Area (allowing free travel).

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Croacia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Croacia para niños

- Bans of Croatia

- Croatian art

- Croatian History Museum

- Croatian Military Frontier

- Croatian nobility

- Culture of Croatia

- History of Dalmatia

- History of Hungary

- History of Istria

- Hundred Years' Croatian–Ottoman War

- Kingdom of Dalmatia

- Kingdom of Slavonia

- Kings of Croatia

- List of noble families of Croatia

- List of rulers of Croatia

- Military history of Croatia

- Timeline of Croatian history

- Turkish Croatia

- Twelve noble tribes of Croatia

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |