History of Dalmatia facts for kids

The History of Dalmatia is about the area along the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea and its nearby inland regions. This story stretches from about 200 BC to today. Around 1,000 BC, the region was home to Illyrian tribes, including the Delmatae. They formed a kingdom, and Dalmatia is named after them! Later, the powerful Roman Empire took control, making Dalmatia a Roman province. In the early 4th century, rough tribes attacked Dalmatia.

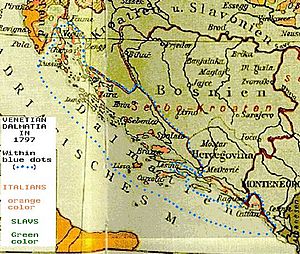

In the 6th and 7th centuries, Slavs, including Croats, began to settle here. These new arrivals created the Kingdom of Croatia and other Slavic areas. Many powerful groups like the Byzantines, Hungarians, Venetians, and Ottomans all fought for control of Dalmatia. In the south, the Republic of Ragusa (1358-1808) became a strong independent city-state. The Republic of Venice controlled a large part of Dalmatia from 1420 to 1797 (see Venetian Dalmatia).

In 1527, the Kingdom of Croatia became part of the Habsburg lands. Later, in 1812, the Kingdom of Dalmatia was formed. After World War I, Dalmatia joined the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, which then became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. After World War II, Dalmatia became part of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia within SR Croatia.

Contents

Ancient Times: Illyrians and Romans

Who were the Illyrians?

Around 1000 BC, the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea was home to the Illyrians. These were people from the western Balkans. Starting in the 8th century BC, several Illyrian kingdoms grew in this area. They traded with and were influenced by nearby Greek kingdoms.

A Greek historian named Polybius described Illyrian society. He said peasant soldiers fought for rich leaders, who controlled towns. Their kings ruled by family line and used marriages to make alliances with other powerful groups.

Three Greek settlements were built on Dalmatian islands: Pharos (Hvar), Issa (Vis), and Black Korkyra (Korčula).

Rome's Conquest of Illyria

In 229 BC, Rome began a series of wars called the Illyro-Roman Wars to conquer Illyria. These wars lasted for over 200 years, until 9 AD. A key figure in the Second Roman-Illyrian War was Demetrius of Pharos (Hvar). In 222 BC, he became a leader of the Illyrian Ardiaean Kingdom. He broke their alliance with Rome and joined forces with Macedonia. He even led a fleet of 90 ships to Greece!

In 180 BC, the Illyrian tribe called the Delmatae declared themselves independent from the Illyrian king, Gentius. They formed their own republic. Their capital was Delminium (now Tomislavgrad). Their land stretched from the Neretva river north to the Cetina river, and later to the Krka river.

After the fall of the Illyrian Ardiaean Kingdom in the south, the Delmatae were the strongest group fighting against the Romans. A series of Roman-Dalmatian Wars were fought for control of Dalmatia. The first war (156 BC – 155 BC) ended with the Roman army destroying the Delmatae capital, Delminium. More wars happened in 118-117 BC and 78 BC-76 BC. The last one ended with Rome capturing the Delmatae stronghold of Salona (near modern Split). There were more uprisings against Rome in 34 BC, when Rome captured Klis, and during the Great Illyrian Revolt in 6-9 AD. This huge revolt involved half a million fighters and civilians!

Roman Rule in Dalmatia

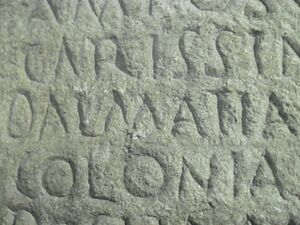

After the Illyrian wars, Dalmatia became more Roman, much like Gaul (France) and Hispania (Spain). The Roman province of Dalmatia spread inland to cover the Dinaric Alps and most of the eastern Adriatic coast. Its capital was the city of Salona (Solin).

Emperor Diocletian made Dalmatia famous by building a huge palace for himself a few kilometers south of Salona, in a place called Aspalathos, which is now Spalatum (Split). Other important Dalmatian cities at that time included Zadar, Trogir, Dubrovnik, and Kotor.

Dividing the Roman Empire

The Roman Emperor Diocletian (who ruled from 284 to 305 AD) changed how the empire was governed. He created the Tetrarchy, which divided the empire into Western and Eastern parts. Each part was led by an "Augustus," who had a chosen successor called a "Caesar."

In Diocletian's system, Dalmatia was part of the Eastern Court, led by Diocletian. But it was managed by his Caesar, Galerius, who lived in the city of Sirmium. In 395 AD, Emperor Theodosius I permanently split the empire, giving his two sons control of the West and East. This time, Spalatum and Dalmatia became part of the Western Court, led by Honorius.

In 468 AD, Flavius Julius Nepos became the ruler of Dalmatia. Four years later, in 472, the Western Emperor Anthemius was killed. The Eastern Emperor, Leo I the Thracian, chose Nepos to be the new Western Emperor. In June 474, Nepos sailed to Ravenna (the Western capital), forced the current emperor to step down, and took the throne.

However, in 475, his general Orestes forced Nepos to flee back to Salona. Orestes' son, Romulus Augustulus, was made emperor, but he was removed the next year. Odoacer, the general who removed Romulus Augustulus, ended the Western Empire. But Julius Nepos continued to rule in Dalmatia until 480 AD, still seen as the true Western Emperor.

Byzantine Rule in Dalmatia

After the Western Roman Empire fell in 481 AD, Dalmatia was briefly ruled by Goths like Odoacer and Theodoric the Great, who also controlled Italy. During the rule of the Ostrogoths, Dalmatia was joined with the Pannonian area (south of the Drava river) into one military region, governed from Salona.

In 545 AD, during Justinian I's war against the Ostrogoths, Dalmatia became part of the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. It was ruled from Constantinople and became a Byzantine province.

In the 6th and 7th centuries, Slavs and Avars gradually arrived in Dalmatia. They conquered many Dalmatian cities like Salona and Epidaurum. The old borders between provinces disappeared. The Byzantines only held a narrow strip of coastal towns and islands, while the inland areas became Slavic.

By 751 AD, what was left of Byzantine Dalmatia (coastal cities like Zadar, Trogir, Split, Dubrovnik, and Kotor, plus some islands) was organized into a separate "Dalmatian theme." This was managed by a Byzantine general in Zadar. For centuries, until the early 13th century, Split remained under Byzantine control. However, its inland areas were often controlled by Croatian, Venetian, or Hungarian rulers. The city of Split had a lot of freedom because the Byzantine government was often busy or weak.

Middle Ages in Dalmatia

After the big Slavic migration into Illyria in the 6th century, Dalmatia became divided into two main groups:

- The inland areas, which had lost many people due to Barbarian Invasions, were settled by Slavic tribes, mostly Croats. There were also some Romanized Illyrian natives and Celts in the north.

- The Byzantine areas, which were coastal towns like Ragusa, Iadera, Tragurium, Spalatum, and Cattaro. These were populated by people who spoke a Romance language called Dalmatian, descended from Romans and Illyrians.

|

|---|

The Duchy and Kingdom of Croatia

As Slavs arrived and formed their own states, the Roman province of Dalmatia changed. By the 9th century, the name "Dalmatia" mostly referred to a narrow coastal and island area under Byzantine influence, called the Theme of Dalmatia.

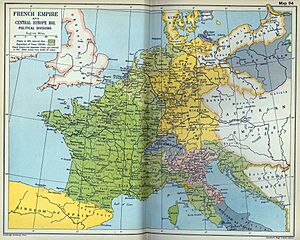

The most important Slavic state in the former Roman Dalmatia was the Duchy of Croatia. Borna of Croatia (803–821) was one of its earliest known rulers. In 806, Dalmatia was briefly part of the Frankish Empire. But the coastal cities were given back to Byzantium by the Treaty of Aachen in 812.

Friendly relations between the coastal cities and the Croatian duchy began with Duke Mislav (835). He signed a peace treaty with the Venetian leader in 840. He also started giving land to churches in the cities. Dalmatia's Croatian Duke Trpimir (ruled 845–864) greatly expanded the new Duchy. He founded the House of Trpimir. His lands reached the Drina river, covering all of Bosnia. He fought against the Bulgars and Serbs. Arab pirates attacked southern cities in 840 and 842, but a joint Frankish-Byzantine effort ended this threat in 871.

From the time of Duke Branimir of Croatia, Venetians had to pay taxes to Croatia and the Narentines for their ships. The Dalmatian city-states paid tribute to the Croatian ruler.

Duke Tomislav created the Kingdom of Croatia in 924 or 925. He was crowned in Tomislavgrad. His powerful kingdom spread its influence south to Duklja. Between 986 and 990, King Stephen Držislav was given the title "Patriarch and Exarch of Dalmatia" by the Byzantine Emperor Basil II. This gave him formal power over the Theme of Dalmatia.

As the Croatian Duchy became a kingdom after 925, its capitals were in Dalmatia. These included Biaći, Nin, Split, and Knin. Many Croatian noble families, who had the right to choose the Croatian ruler, were from Dalmatia.

Croatian kings collected tribute from Byzantine cities like Tragurium and Iadera. They also strengthened their power in Croatian towns like Nin and Šibenik. The city of Šibenik was founded by Croatian kings!

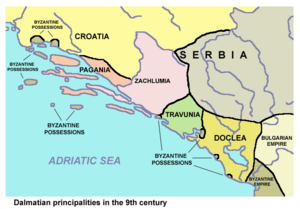

Southern Dalmatian Principalities

The southern part of Dalmatia was divided into four smaller areas: Pagania, Zahumlje, Travunia, and Duklja. Pagania was a small duchy between the Cetina and Neretva rivers. Zahumlje and Travunia stretched further inland than today's Dalmatia. Duklja began south of Dubrovnik and went down to Skadar Lake.

Pagania: The Pirate Land

Pagania got its name because its people were still pagan when nearby tribes were Christian. The pirate-like people of Pagania (also called Narenta, after the Narenta river) were skilled pirates. They attacked Venetian ships in the Adriatic in 827 and 828. When the Venetian fleet returned, the Narentines retreated. But when the Venetians left, the Narentines would start raiding again.

In 834 and 835, they captured and killed several Venetian traders. To punish them, the Venetian leader launched a military attack in 839. The war continued with the Dalmatian Croats joining in. A truce was quickly signed, but only with the Dalmatian Croats and some Pagan tribes. In 840, the Venetians attacked the Narentine Prince Ljudislav, but failed. In 846, a new operation attacked the Slavic land of Pagania, destroying one of its main cities. But this didn't stop the Narentines, who kept raiding and stealing from the Venetians.

It wasn't until 998 that the Venetians finally gained control. Their leader, Peter II Orseolo, crushed the Narentines and took the title "Duke of the Dalmatians." In 1050, the Narentines became part of the Kingdom of Croatia under King Stjepan I.

Zahumlje: Land of Hum

Zahumlje was named after the mountain of Hum near Bona, where the Buna river flowed. It included the old cities of Bona and Hum. Zahumlje covered parts of modern-day Herzegovina and southern Dalmatia. Zahumlje's first known ruler was Michael of Zahumlje. He was mentioned with Tomislav of Croatia in a letter from Pope John X in 925. Michael remained ruler of Zahumlje through the 940s, keeping good relations with the Pope.

Travunia: A Fiefdom's Story

Travunia was first a town, now Trebinje. It became a fiefdom during the rule of Vlastimir of Serbia. It was ruled by one family until the next century. Dragomir Hvalimirović restored the title of Travunia, but he was killed around 1010. The coastal lands were then taken by the Byzantines, and later by Serbia. Travunia remained part of Serbia until 1377, when Bosnian Ban Tvrtko took the area.

Venice, Hungary, and Local Power

As the Dalmatian city-states lost Byzantine protection, they had to seek help from either Venice or Hungary. Each of these powerful groups had supporters within the Dalmatian cities, mostly for economic reasons.

The Venetians, who shared language and culture with the Dalmatians, offered good terms. Their main goal was to prevent any strong rivals from growing on the eastern Adriatic. In exchange for protection, the cities often provided soldiers or ships and sometimes paid tribute in money or goods. For example, Arbe (Rab) paid Venice ten pounds of silk or five pounds of gold each year.

Hungary, on the other hand, defeated the last Croatian king in 1097 and claimed all Croatian lands. King Coloman conquered Dalmatia between 1102 and 1105. Farmers and traders who dealt with the inland areas preferred Hungary. Hungary was their most powerful neighbor on land and confirmed their city rights.

Cities could elect their own leaders, bishops, and judges. Their Roman laws remained valid. They could even make their own alliances. No foreigner, not even a Hungarian, could live in a city if they were not welcome. People who disliked Hungarian rule could leave with all their belongings. Instead of tribute, the income from customs duties was sometimes shared equally by the king, city leader, bishop, and city.

However, these rights were often ignored. Hungarian soldiers were stationed in unwilling towns, and Venice interfered with trade and city appointments. Because of this, Dalmatians were loyal only when it suited them, and revolts often happened. Even in Zadar, there were four uprisings between 1180 and 1345, even though Zadar was treated well by Venice.

In 1202, crusaders agreed to transport to the Holy Land for Venice. As payment, Venice demanded help to capture Zadar. Despite Pope Innocent III forbidding an attack on a Christian city, the Venetians and crusaders attacked and sacked the city. The Pope excommunicated them. After wintering in Zadar, the Fourth Crusade continued, leading to the siege of Constantinople. In 1204, this army conquered Byzantium, removing the Eastern Empire as a player in Dalmatia.

The early 13th century was peaceful. Dalmatian cities accepted foreign rule (mainly Venice), but eventually wanted independence again. The Mongol invasion greatly weakened Hungary. In 1241, King Béla IV had to hide in Dalmatia (in the Klis fortress). The Mongols attacked Dalmatian cities for a few years but then left.

Croats were no longer seen as enemies by city people. In fact, powerful Croatian nobles, like the counts Šubić of Bribir, sometimes ruled the northern areas (between 1295 and 1328). In 1344, Zadar rebelled against Venice again. The Venetians crushed the rebellion with 20,000-30,000 troops and their navy during the Siege of Zadar (1345-1346). In 1346, the Black Death hit Dalmatia. The economy was also bad, and cities became more dependent on Venice.

Stephen Tvrtko I, who founded the Bosnian kingdom, took control of the Adriatic coast between Kotor and Šibenik in 1389. He even claimed control over the northern coast up to Fiume (Rijeka), except for Venetian-ruled Zadar and independent Ragusa (Dubrovnik). This was temporary. Hungarians and Venetians continued fighting over Dalmatia after Tvrtko died in 1391.

An internal struggle in Hungary also affected Dalmatia. In the early 15th century, all Dalmatian cities welcomed the Neapolitan fleet, except Dubrovnik. The Bosnian duke Hrvoje Vukčić Hrvatinić controlled Dalmatia for the Angevins, but later switched loyalty. This struggle weakened Hungarian influence. In 1409, Ladislaus of Naples sold his "rights" over Dalmatia to Venice for 100,000 Ducats. Venice gradually took over most of Dalmatia by 1420. In 1437, Sigismund recognized Venetian rule over Dalmatia.

From 1448 to 1482, the Duchy of St. Sava held Herzegovina and southern Dalmatia. In 1482, it was taken by the Ottoman Empire. Only the Republic of Ragusa remained independent.

The Republic of Ragusa (Dubrovnik)

The history of Ragusa (Dubrovnik) goes back to at least the 7th century. After the fall of the Ostrogothic Kingdom, the town was protected by the Byzantine Empire. In the 12th and 13th centuries, Dubrovnik grew into a republic ruled by a few powerful families. It became an important trading post for the Serbian and Bosnian states.

After the Crusades, Dubrovnik was under the rule of Venice (1205–1358). Ragusa grew by buying islands and land from Serbia. By the Peace Treaty of Zadar in 1358, Dubrovnik became mostly independent as a vassal state of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Between the 14th century and 1808, Dubrovnik ruled itself as a free state. It paid tribute to the Ottoman Empire from 1382 to 1804. The Republic was strongest in the 15th and 16th centuries. Its ships sailed as far as India and America, competing with Venice and other Italian sea powers. The city became a center of culture, especially for literature written in the local Slavic language, which became the basis for today's Croatian.

Languages in Dalmatia

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, towns on the Dalmatian coast continued to speak Latin. Their language developed on its own, becoming a unique language called Dalmatian (now extinct). The earliest mention of this language is from the 10th century. It's thought that about 50,000 people spoke it along the eastern Adriatic coast at that time.

Dalmatian speakers lived mainly in coastal towns like Zadar, Trogir, Split, Dubrovnik, and Kotor. Each city had its own dialect. The most important ones were Vegliot (spoken on Krk island) and Ragusan (spoken in Dubrovnik). The Zadar dialect disappeared, mixing with Venetian due to Venice's strong influence. The other dialects also faded as Slavic languages became more common.

The once rival Romanic and Slavic populations eventually started building a common culture. Ragusa (Dubrovnik) was a great example of this. By the 13th century, the names of council members in Ragusa were mixed. By the 15th century, Ragusan literature was even written in the Slavic language (which Croatian comes from). The city was often called by its Slavic name, Dubrovnik.

Religion in Dalmatia

The split in Christianity was important in Dalmatia's history. The Croatian Catholic Church in Nin was under the Papal authority, but they used the Slavic liturgy (church service). Both the Latin-speaking people in the cities and the Holy See (Pope's office) preferred the Latin liturgy. This caused tension between different church areas. The Croatian people preferred local priests who were married and spoke Croatian during mass, so they could be understood.

The Great Schism between Eastern and Western Christianity in 1054 made the divide between the coastal cities and the inland areas even stronger. Some Slavs in southeastern Dalmatia preferred Eastern Orthodoxy. Areas of today's Bosnia and Herzegovina also had their own Bosnian Church.

Latin influence in Dalmatia grew, and Byzantine practices were suppressed at church meetings. For example, the bishopric of Nin was demoted, and the archbishoprics of Spalatum (Split) and Dioclea (Montenegro) were established. Using any liturgy other than Greek or Latin was forbidden.

As the Grand Principality of Serbia grew, the Nemanjić dynasty gained control of the southern Dalmatian states by the late 12th century. Here, the population was Catholic. The Nemanjić Serbia controlled several southern coastal cities, like Kotor and Bar.

Culture and Identity

Dalmatia never became a single political or ethnic nation. But it achieved amazing progress in art, science, and literature. The Neo-Latin Dalmatian city-states were often isolated. They had to rely on Venice for support or try to be independent.

Dalmatia's location explains why Byzantine culture had a relatively small influence, even though Dalmatia was part of the Eastern Empire for six centuries (535–1102). Towards the end of this period, Byzantine rule became more symbolic, while Venice's influence grew.

Medieval Dalmatia still included much of the inland area of the old Roman province. However, the name "Dalmatia" began to refer more to just the coastal, Adriatic areas, rather than the mountains inland. By the 15th century, the word "Herzegovina" was introduced, showing that Dalmatia's borders were shrinking to a narrow coastal strip.

Early Modern Period: Venice and Ottomans

Divided Dalmatia (15th-18th Century)

The Republic of Venice controlled a large part of Dalmatia from 1420 to 1797 (see Venetian Dalmatia). A period of peace followed, but the Ottoman Empire kept advancing. When the Ottomans arrived, Venice controlled the islands and coastal areas, while the Hungarian-Croatian Kingdom held most of the Dalmatian hinterland. Christian kingdoms and regions to the east fell one by one: Constantinople in 1453, Serbia in 1459, neighboring Bosnia in 1463, and Herzegovina in 1483.

Dubrovnik stayed safe by being friends with the Ottomans. In one case, it even sold two small strips of its land (Neum and Sutorina) to the Ottomans. This was to prevent Venice from having land access to Dubrovnik.

In 1508, the League of Cambrai forced Venice to bring its soldiers home. After Hungary's defeat in 1526, the Turks easily conquered most of Dalmatia by 1537. This happened when the Siege of Klis ended with the fall of the Klis Fortress to the Ottomans. This led to the formation of the Sanjak of Klis, part of the Eyalet of Bosnia.

With the fall of the Hungarian-Venetian border in Dalmatia, Venetian Dalmatia now directly bordered the Ottoman Empire. Venice still called this inland area "Banadego" (lands of the Ban, meaning a Banate). Venetian Dalmatia controlled most of the important sea points in the Eastern Adriatic between 1420 and 1797. Ottoman Dalmatia, between 1499 and 1646, had access to the sea between Omiš and Poljica and in Obrovac.

Christian Croats from nearby lands now flocked to the towns. They outnumbered the Romanic population even more, making Croatian the main language. The "uskoks" were a group of these refugees, especially near Senia. Their actions led to a new war between Venice and Turkey (1571–1573). Reports from Venetian agents describe this war like a medieval knightly story, full of duels and adventures. They also show that Dalmatian soldiers were much better than Italian mercenaries. Many of these troops served abroad. At the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, a Dalmatian squadron helped the allied fleets defeat the Turkish navy.

The Venetian Republic promised the peasants in the hinterland freedom from feudal lords if they served in the military. The Roman Catholic Church, as the religion of both Venetians and Croats, had a major influence. The Serbian Patriarchate of Peć (later the Serbian Orthodox Church) was also active in Dalmatia, mostly in Ottoman-controlled areas where many Christians converted to Islam. Orthodox Slavs often came as soldiers for the Ottomans. Orthodoxy is linked to the Ottoman history of the region. "Orthodox Dalmatia" (as Serbs call it) emerged due to Ottoman and Venetian conquests, creating the later religious borders between Catholics and Orthodox people in Dalmatia.

During the War of Candia (1645-1669) and the Great Turkish War (1683-1699), Venice gained almost all of Dalmatia down to Ston, and the region beyond Ragusa, from Sutorina to Boka kotorska. After the Venetian-Turkish war (1714–1718), Venice's land gains were confirmed by the 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz.

Dalmatia experienced strong economic and cultural growth in the 18th century. Trade routes with the inland areas were reopened in peacetime. Because the Venetians reclaimed some inland territories in the north during the Turkish wars, the name "Dalmatia" was no longer just for the coast and islands. The border between the Dalmatian hinterland and Ottoman Bosnia and Herzegovina changed a lot until the Morean War. Then, Venice's capture of Knin and Sinj set much of the border at its current position. This period ended suddenly with the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797.

Modern Era: Changes and Conflicts

Dalmatia in the Napoleonic Era

In 1797, in the treaty of Campo Formio, Napoleon I gave Dalmatia to Austria in exchange for Belgium. The republics of Ragusa (Dubrovnik) and Poljica remained independent. Ragusa grew rich by staying neutral during the early Napoleonic wars.

By the Peace of Pressburg in 1805, Istria, Dalmatia, and the Bay of Kotor were given to France. In 1805, Napoleon created his Kingdom of Italy around the Adriatic Sea, adding the former Venetian Dalmatia to it.

In 1806, the Republic of Ragusa (Dubrovnik) finally fell to French troops led by General Marmont. The same year, a Montenegrin force, supported by the Russians, tried to fight the French by taking Boka Kotorska. The allied forces pushed the French to Ragusa. The Russians convinced the Montenegrins to help, and they took the islands of Korčula and Brač. But they didn't advance further and withdrew in 1807 under the Treaty of Tilsit. The Republic of Ragusa was officially added to Napoleon's Kingdom of Italy in 1808.

In 1809, the War of the Fifth Coalition began, and French and Austrian forces fought in the Dalmatian Campaign (1809). Austrian forces briefly retook Dalmatia that summer. But this only lasted until the Treaty of Schönbrunn, when Austria gave more provinces north of Dalmatia to France. So, Napoleon removed Dalmatia from his Kingdom of Italy and created the Illyrian Provinces.

Most of the Dalmatian population was Roman Catholic. From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, Italian and Slavic communities in Dalmatia lived peacefully. They didn't identify as separate nations, but rather as "Dalmatians" of "Romance" or "Slavic" culture.

Habsburg Austrian Rule and Nationalism

In the War of the Sixth Coalition, the Austrian Empire declared war on France in 1813. Austria regained control over Dalmatia by 1815 and formed a temporary Kingdom of Illyria. In 1822, this was ended, and Dalmatia was placed under direct Austrian rule.

Like elsewhere in 19th-century Europe, nationalism grew in Dalmatia. Slavic-speaking people increasingly identified as Croats and Serbs, and Italian-speakers as Italians. The Habsburg Empire had its own plans for Dalmatia. It opposed the creation of an Italian state but supported the development of Italian culture in Dalmatia. This was a careful balance to serve its own interests.

At the time, most rural people spoke Croatian, while the city's upper class spoke Italian. In the first Austrian census of 1865, Italian speakers made up 12.5% of the population. The Italian-leaning upper class first promoted a separate Dalmatian identity under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. This helped them keep the privileged social status they had under Venice.

In the 1860s, two main political groups appeared in Dalmatia. The first was pro-Croatian, advocating for Dalmatia to join the rest of Croatia under Hungarian rule. The second was autonomist and pro-Italian. In the 1861 election, the autonomists won. But as more citizens gained voting rights, the Croatian parties gained the majority in 1870. Many arguments were about language. Local Italian officials, against Austrian laws, declared only Italian as the official language.

Among Croatians, who were the majority, a pan-South-Slavic movement emerged in the first half of the 19th century. This movement aimed to create a Croatian national identity within Austria-Hungary through language and ethnic unity. This was part of the Croatian national revival. In the 1860s, more nationalist Croatian leaders saw Austria as their main enemy. In Dalmatia, growing nationalism meant seeking to unite Dalmatia with other Croatian lands in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. They also fought for language rights for the Croatian majority, which they felt were suppressed by the Italian-speaking elite.

Many Dalmatian Italians supported the Risorgimento movement, which aimed to unite Italy. However, after 1866, when the Veneto and Friuli regions were given to the new Kingdom Italy, Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This led to the rise of Italian irredentism among many Italians in Dalmatia. They demanded that Dalmatia join Italy.

The Italians in Dalmatia supported Italian unification. As a result, the Austrians saw Italians as enemies and favored the Slavic communities, encouraging Croatian nationalism. In 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria ordered strong action against Italian influence in certain regions, promoting Germanization or Slavization.

Dalmatia, especially its coastal cities, once had a significant local Italian population (Dalmatian Italians). They made up 33% of Dalmatia's population in 1803, but this dropped to 20% in 1816. According to Austrian censuses, Dalmatian Italians were 12.5% of the population in 1865, but only 2.8% in 1910. The Italian population in Dalmatia constantly declined, partly due to aggressive anti-Italian policies and forced Slavization by the Austrians.

The Italian population in Dalmatia was mostly in the larger coastal cities. In Split in 1890, there were 1,969 Dalmatian Italians (12.5% of the population). In Zadar, there were 7,423 (64.6%). In other Dalmatian places, the number of Dalmatian Italians decreased sharply.

Political alliances in Dalmatia changed over time. At first, the unionists (pro-Croatian) and autonomists (pro-Italian) were allied against Vienna's central rule. Later, when national identity became more important, they split. A third split happened when the local Orthodox population, few of whom were nationally conscious Serbs, heard about the idea of uniting all Serbs through the Serbian Orthodox Church. As a result, the Serbian Orthodox population started to side with the autonomists and irredentists rather than the unionists.

20th Century: Wars and Changes

First Half of the 20th Century

In 1909, Italian lost its official language status in Dalmatia, with only Croatian recognized. This meant Italian could no longer be used in public and administrative life.

In World War I, Austria-Hungary was defeated and broke apart. This helped solve the internal political conflict in Dalmatia. Under the Treaty of London in 1915, Italy was supposed to get northern Dalmatia (including Zadar, Šibenik, and Knin). But after World War I, Italy only got a smaller area. Dalmatia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. After talks, only Zadar (officially "Zara" in Italian) and the islands of Cres, Lošinj, and Lastovo remained part of the Kingdom of Italy.

When the Croatian Banate was formed in 1939, most of Dalmatia was included in it.

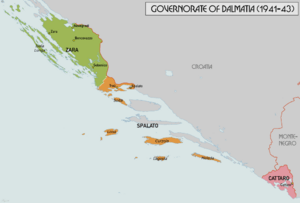

In April 1941, during World War II, the Axis powers invaded and conquered Yugoslavia. A month later, large parts of Dalmatia were taken by the Kingdom of Italy (forming the Governorate of Dalmatia). The rest was formally left to the Independent State of Croatia, but Italian forces occupied it and later supported Chetniks in Serb-populated areas.

Many Croats from Dalmatia joined the resistance movement led by Tito's Partisans. Others joined the fascist Croatia of Ante Pavelić. This led to a terrible guerrilla war that devastated all of Dalmatia.

In September 1943, after Italy surrendered, Partisans temporarily controlled large parts of Dalmatia. But then, the German Wehrmacht reoccupied these areas. Later in the war, many Dalmatian Croats went into exile, fearing German revenge. In the second half of 1944, Partisans, supplied by the Allies, finally took control of all Dalmatia. The Italian population of Dalmatia, mostly in Zadar, suffered huge losses due to Allied bombings in 1944.

After 1945, most of the remaining Dalmatian Italians fled the region (350,000 Italians left Istria and Dalmatia in the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus). They were seen as remnants of the occupation force and were given the option to leave for Italy. Some died in the so-called foibe massacres, though this was more common in Istria than in Dalmatia. The "disappearance" of Italian-speaking populations in Dalmatia was almost complete after World War II. Italians were 33% of the Dalmatian population in 1803, but today there are only about 300 Italians in Croatian Dalmatia and 500 in coastal Montenegro.

After World War II, Dalmatia was divided among three republics of socialist Yugoslavia. Almost all the territory went to Croatia, leaving Bay of Kotor to Montenegro and a small strip of coast at Neum to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Breakup of Yugoslavia and Homeland War

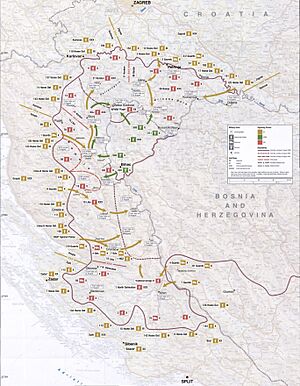

In 1990, as Yugoslavia began to break apart, Croatian leaders announced their plan to declare independence, which they did in 1991. The first battlefields of what would be called the Homeland War (Domovinski rat) appeared in northern Dalmatia. This area had a significant Serb population. They rebelled, encouraged and helped by Serbian nationalist groups. They formed their own SAO Kninska Krajina and started the "Log Revolution." The center of this unrest was the northern Dalmatian town of Knin.

This Serb-held region later became the SAO Krajina, and then the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK), combined with other Serb-held regions across Croatia. The RSK was helped by the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and paramilitary troops from Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. Serbian forces had more equipment and weapons because of JNA support. They committed various acts of violence, including shelling civilian areas.

The Yugoslav People's Army operated from their barracks, mostly in larger cities and important strategic points. In some bigger cities, the JNA had built large residential buildings. At the start of the war, it was thought these buildings would be used by snipers or for spying.

The battle for control of Dalmatia during the Croatian War of Independence was fought on three main fronts:

- The land front between Knin and the cities of Zadar, Šibenik, and Sinj.

- The sea front near Split.

- The land front near the border with Montenegro and Herzegovina, including the Siege of Dubrovnik.

First attempts to take over JNA facilities in August in Sinj failed. But a major action took place in September 1991. The Croatian Army and police were more successful, taking over repair shops, warehouses, and similar facilities. Major bases, commanded by loyal officers and manned by reservists, became standoffs that usually ended with JNA personnel and equipment being evacuated under international supervision. This process finished shortly after the Sarajevo armistice in January 1992.

All non-Serb people were forced out of Serb-controlled areas, notably the villages of Škabrnja (Škabrnja massacre) and Kijevo (siege of Kijevo). Tens of thousands of Croatian refugees found shelter in Dalmatian coastal towns, where they were placed in empty tourist facilities.

On May 2, 1991, the 1991 anti-Serb riot in Zadar happened. In this event, 168 Serb-owned shops were looted by Croatian civilians.

By early 1992, military positions were mostly set, and the RSK's expansion stopped. Serbian forces continued random shelling of Croatian cities, which happened occasionally for the next four years.

Besides the northern inland area bordering Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Yugoslav People's Army also occupied parts of southern Dalmatia around Dubrovnik, as well as the islands of Vis and Lastovo. These occupations lasted until 1992.

The United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) was deployed in UN-protected zones, including northern Dalmatia.

The Croatian government gradually regained control over all of Dalmatia through military operations:

- September 1991: September War for Šibenik - successful defense of Šibenik from JNA attacks and takeover of JNA bases.

- May and July 1992: Operation Tiger - JNA was forced to retreat from Vis, Lastovo, Mljet, and areas around Dubrovnik.

- July 1992: Miljevci Heights in the Šibenik hinterland were liberated in the Miljevci Plateau incident.

- January 1993: Operation Maslenica - Croatian forces liberated Zadar and Biograd hinterland.

- In August 1995, Croatian forces conducted Operation Storm, ending the Krajina and restoring Croatian control to internationally recognized borders.

During Operation Storm, most of the Serb population from Krajina left their homes. A minority stayed. Homes left by ethnic Serbs were taken over by ethnic Croatian refugees from Bosnia-Herzegovina, with help from Croatian authorities. Over the past decade, some ethnic Serb refugees have returned, gradually changing the population in certain areas. However, it's unlikely their proportion will reach pre-war levels again.

21st Century: Recovery and Challenges

Dalmatia suffered greatly during the war, especially the inland areas, where much of the infrastructure was destroyed. The tourism industry, which was very important, was deeply affected by negative publicity. It didn't fully recover until the late 1990s.

The Dalmatian population generally saw a dramatic drop in living standards. This created a gap between Dalmatia and the more prosperous northern parts of Croatia. This gap was reflected in strong nationalism, which had visibly higher support in Dalmatia than in the rest of Croatia.

This was seen not only in Dalmatia being a strong supporter of the Croatian Democratic Union and other right-wing parties, but also in large protests against Croatian Army generals being tried for war crimes. The charges against General Mirko Norac in early 2001 brought 150,000 people to the streets of Split. This was arguably the largest protest in modern Croatian history.

See also

- Dalmatia

- History of Croatia

- Italianization

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |