Pannonian Avars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Avar Khaganate

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 567 – after 822 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Avar Khaganate and surroundings circa 602.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Originally shamanism and animism, Christianity after 796 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Khanate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khagan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

567 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Defeated by Pepin of Italy

|

796 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

after 822 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Pannonian Avars were a group of different nomadic people from Europe and Asia. They were also called the Obri or Varchonitai. They created the Avar Khaganate, a powerful empire. This empire stretched across the Pannonian Basin (a large plain in Central Europe) and other parts of Central and Eastern Europe. It lasted from the late 500s to the early 800s.

We call them "Pannonian Avars" because they settled in the Pannonian Basin. This helps tell them apart from other groups called Avars who lived in the Caucasus mountains. The name "Avar" first appeared in the mid-400s. But the Pannonian Avars became important in the mid-500s. They came from the Pontic–Caspian steppe (a large grassland) because they wanted to escape the rule of the Göktürks. They are famous for their attacks and destruction during the Avar–Byzantine wars (568 to 626). They also influenced the movement of Slavic people into the Balkans.

New studies of ancient DNA show that the Avar leaders had Northeast Asian roots. This is similar to people from Mongolia today. But most of the common people in the Avar Khaganate were like the European groups around them. Some experts also think that some Avars might have spoken Iranian languages.

Contents

Where Did the Avars Come From?

Early Mentions of the Avars

The first clear mention of the Avars is around 463 AD. A writer named Priscus said that the Šaragurs and Onogurs were attacked by the Sabirs. The Sabirs had been attacked by the Avars. These Avars were running away from "man-eating griffins" from "the ocean." It's not clear if these early Avars were the same group who appeared later.

In the 500s, another writer, Menander Protector, wrote about the Göktürks. The Turks were angry at the Byzantines for making a deal with the Avars. The Turks saw the Avars as their subjects. A Turkic prince called the Avars "Varchonites" and "escaped slaves of the Turks." He said there were about 20,000 of them.

Another writer, Theophylact Simocatta, wrote more about the Avars around 629 AD. He said that the Turks defeated a group called the Abdali (Hephthalites) and then enslaved the Avar nation. He also said that the Avars who came to Europe were not the "real" Avars. He called them "Pseudo-Avars." He claimed they were actually two groups, the Var and the Chunni, who pretended to be Avars because the name was powerful.

Historians debate these stories. Some think the Turks wanted to show they were the strongest power. They might have called the Avars "pseudo-Avars" to make them seem less important.

Different Groups and Their Origins

Some scholars believe the Pannonian Avars came from a group formed near the Aral Sea. This group included the Uar and the Xionites. These people likely spoke Iranian or Turkic languages. The Pannonian Avars were also known as Uarkhon or Varchonites. This name might be a mix of "Var" and "Chunni."

Some historians connect the Avars to the Rouran Khaganate from Inner Asia. Chinese records say that the Rouran were defeated by the First Turkic Khaganate. Some Rouran people fled. This might be similar to the Avars fleeing the Turks. However, these events happened at different times, so the connection is still debated.

Other theories suggest the Avars were of Turkic origin, possibly from the Oghur branch. Some also think they had Tungusic roots. Many experts believe the Avars were a mix of different groups. These included Turkic (Oghuric) and Mongolic people. Later, in Europe, some Germanic and Slavic groups joined them.

How Steppe Empires Formed

Historians explain that many steppe empires were started by groups who lost earlier power struggles. These groups would flee and then try to build their own power. The Avars might have been a group that lost to the Ashina clan of the Western Turkic Khaganate. They then fled west.

These new groups were usually a mix of different peoples. They would choose a new leader, called a Khagan, to show they were independent. They also needed a new name to give everyone a shared identity. This new name was often a famous one, like "Huns" or "Avars." This helped them gain respect and show their power.

Avar identity was closely tied to their political system. Groups who rebelled against the Avars were not called "Avars" anymore. They were called "Bulgars" instead. When the Avar empire fell, their identity quickly disappeared.

Studies suggest that the early Pannonian Avars came from Central Asia. They were a mix of Iranian, Ugrian, Oghur-Turkic, and Rouran tribes.

Physical Appearance and Genetics

Early studies of Avar skeletons showed mostly "Europoid" (European-like) features. But their grave goods showed links to the Eurasian Steppe. Later Avar graves (from the 700s) had many skeletons with East Asian or mixed Eurasian features. About one-third of Avar graves from the 700s showed these features.

Recent genetic studies have given us more clues.

- A 2016 study looked at DNA from 31 people in the Carpathian Basin. Most had European DNA, but about 15% had Asian DNA.

- A 2018 study of 62 people in Slovakia found that 93% had West Eurasian DNA and 6% had East Eurasian DNA. Their DNA was similar to medieval and modern Slavs. This suggests Avar men might have married Slavic women.

- A 2019 study of 14 Avar males found that many carried East Asian paternal DNA. This type of DNA is common in modern Northeast Siberian and Buryat people. Most of these Avars likely had dark eyes and dark hair and were mainly of East Asian origin.

- A 2020 study of 26 elite Avars found their paternal DNA was almost all East Asian. This suggests the Avar elite were a very close-knit group for about 100 years. They came to the Pannonian Basin from East Asia, with both men and women migrating.

- Another 2020 study found that the Xiongnu (an ancient East Asian group) shared some DNA with the Huns and Avars. This suggests a possible link between them.

- A 2022 study in Cell analyzed 48 Avar samples. It found they were almost entirely from Ancient Northeast Asians. Their DNA was very similar to modern Mongolic and Tungusic people.

- A 2022 study in Current Biology looked at 143 Avar samples. It confirmed the East Asian origin for the Avar elite. It also showed that the general Avar population was mostly local European people. This means a small group of horse nomads (the Avar elite) ruled over a much larger settled population.

Avar History: From Arrival to Decline

Coming to Europe

In 557 AD, the Avars sent messengers to Constantinople (the capital of the Byzantine Empire). This was their first contact with the Byzantines. For gold, the Avars agreed to fight other "unruly groups" for the Byzantines. They conquered and took in tribes like the Kutrigurs and Sabirs. They also defeated the Antes.

By 562 AD, the Avars controlled the lower Danube river area and the grasslands north of the Black Sea. When they reached the Balkans, they were a mixed group of about 20,000 horsemen. The Byzantine Emperor Justinian I paid them to move on. So, they went northwest into Germania. But the Frankish people stopped their expansion there.

The Avars wanted rich lands for their horses. They first asked for land south of the Danube in present-day Bulgaria. But the Byzantines said no. They even threatened to use their contacts with the Göktürks against the Avars. So, the Avars looked towards the Carpathian Basin. This area had good natural defenses. The Carpathian Basin was held by the Gepids. In 567 AD, the Avars teamed up with the Lombards, who were enemies of the Gepids. Together, they destroyed much of the Gepid kingdom. The Avars then convinced the Lombards to move into northern Italy. This was the last big movement of Germanic people in the Migration Period.

The Byzantines continued to use their strategy of turning different groups against each other. They convinced the Avars to attack the Sclaveni (Slavic people) in Scythia Minor. This land was full of valuable goods. After destroying much of the Sclavenes' land, the Avars returned to Pannonia. Many of the Khagan's people had left to join the Byzantine emperor.

Early Avar Power (580–670 AD)

By about 580 AD, the Avar Khagan Bayan I was in charge of most of the Slavic, Germanic, and Bulgar tribes. These tribes lived in Pannonia and the Carpathian Basin. When the Byzantine Empire couldn't pay the Avars or hire them as fighters, the Avars attacked Byzantine lands in the Balkans. In 568 AD, Bayan led an army of 10,000 Kutrigur Bulgars and attacked Dalmatia. This cut off the Byzantine land connection to Italy and Western Europe.

In the 580s and 590s, many Byzantine armies were fighting the Persians. The remaining troops in the Balkans were not strong enough for the Avars. By 582 AD, the Avars had captured Sirmium, an important fort in Pannonia. When the Byzantines refused to pay more money, the Avars captured Singidunum (Belgrade) and Viminacium. However, they faced problems during Maurice's Balkan campaigns in the 590s.

By 600 AD, the Avars had built a nomadic empire. It ruled over many different peoples. It stretched from modern Austria in the west to the Pontic–Caspian steppe in the east. After being defeated in their homeland in 602 AD, some Avars left to join the Byzantines. But Emperor Maurice kept his army camp beyond the Danube through the winter. This was unusual and caused the army to rebel. This gave the Avars a much-needed break. They tried to invade northern Italy in 610 AD.

The Byzantine civil war led to a Persian invasion. After 615 AD, the Avars had free rein in the undefended Balkans. In 617 AD, while talking with Emperor Heraclius outside Constantinople, the Avars launched a surprise attack. They couldn't capture the city center, but they looted the suburbs and took 270,000 captives. Payments to the Avars reached a huge sum. In 626 AD, the Avars worked with the Sassanid army in a failed attack on Constantinople. After this defeat, the Avars' power began to weaken.

Byzantine and Frankish records show a war between the Avars and their western Slavic allies, the Wends.

Each year, the Huns [Avars] came to the Slavs, to spend the winter with them; [...] the Slavs were [...] forced to pay taxes to the Huns. But the sons of the Huns, who were raised with the wives and daughters of these Wends, could not stand this unfair treatment anymore. They refused to obey the Huns and started a rebellion. When the Wendish army fought the Huns, the merchant Samo went with them. Samo showed great bravery, and many Huns were killed by the Wends.

In the 630s, Samo, the leader of the first Slavic state (Samo's realm), grew stronger. He took control of lands north and west of the Avar Khaganate. He ruled until his death in 658 AD. The Chronicle of Fredegar says that during Samo's rebellion in 631 AD, 9,000 Bulgars left Pannonia. Most of them were killed in Bavaria. The remaining 700 joined the Wends.

Around this time, the Bulgar leader Kubrat led a successful revolt. He ended Avar rule over the Pannonian Plain. He created Old Great Bulgaria. A civil war among the Bulgars happened from 631 to 632 AD. After this, Kubrat made peace between the Avars and Byzantium in 632 AD. A group of Croats also fought against the Avars and then formed the Duchy of Croatia.

Later Avar Periods (670–804 AD)

After Samo died in 658 AD and Kubrat died in 665 AD, some Slavic tribes came under Avar rule again. Kubrat's sons could not keep Old Great Bulgaria together, and it broke into five parts. Some Bulgars moved to Ravenna. Another Avar leader took control of regions further north.

Around 677 AD, the principality of Ungvar was formed. Other Bulgar groups also fled. One group of Bulgarians, led by Khan Asparukh, settled along the Danube around 679–681 AD. They established the First Bulgarian Empire.

Even though the Avar empire became smaller, the Avars and Slavs kept their power in the central Danube region. They also spread their influence west towards the Vienna Basin. New types of pottery and burial sites appeared around 690 AD. These show that settlements in the Carpathian Basin became more stable. Popular Avar designs, like griffins and tendrils on belts and weapons, might show a longing for their old nomadic life. Or they might mean new nomads arrived from the Pontic steppes.

The Avar Khaganate in its later periods was a mix of Avar and Slavic cultures. The Slavic language might have been the most common language spoken. In the 600s, the Avar Khaganate helped Slavic people and their language spread to the Adriatic and Aegean regions.

In the early 700s, a new style of art and objects appeared in the Carpathian Basin. Some theories say this was from new settlers, like early Magyars. But this is still debated. Other historians think it was the Avars themselves changing and mixing with Bulgars who had arrived earlier. Many areas that were once important Avar centers lost their importance. New ones grew.

The Fall of the Avars

The Avars' power slowly declined, then fell quickly. A series of Frankish attacks, starting in 788 AD, led to the conquest of the Avar lands within ten years. The first fight between Avars and Franks happened after the Franks took control of Bavaria in 788 AD. The Avars attacked Bavaria, but they were pushed back. Frankish forces then attacked Avar lands along the Danube. The Avars were defeated in 788 AD. This showed the rise of Frankish power and the decline of the Avars.

In 790 AD, the Avars tried to make peace with the Franks, but they couldn't agree. A Frankish campaign against the Avars in 791 AD was successful. A large Frankish army, led by Charlemagne, marched into Avar territory. They found no resistance because the Avars had fled. Disease also killed most of the Avar horses. Fighting among the Avar tribes began, showing how weak their empire was.

The Franks were helped by the Slavs, who formed their own states on former Avar land. Charlemagne's son Pepin of Italy captured a large, fortified camp called "the Ring." This camp held much of the treasure the Avars had taken in earlier wars. By 796 AD, the Avar leaders had surrendered. They were open to becoming Christians. All of Pannonia was conquered. The Franks baptized many Avars and made them part of the Frankish Empire. In 799 AD, some Avars revolted.

In 804 AD, Bulgaria conquered the southeastern Avar lands. Many Avars became subjects of the Bulgarian Empire. Khagan Theodorus, who had become a Christian, died in 805 AD. He was followed by Khagan Abraham, who was also baptized. The Franks turned the Avar lands they controlled into a border region. This region was given to the Slavic Prince Pribina.

Whatever was left of Avar power ended when the Bulgars expanded their territory around 829 AD. Historians say that Avars were still present in Pannonia in 871 AD. But after that, their name is no longer used in records. It seems they couldn't keep their Avar identity after their empire fell. However, archaeological findings suggest that a significant Avar population remained in the Carpathian Basin in the late 800s.

Byzantine records from the 800s mention the Avars as an existing Christian people. The Avars had been mixing with the more numerous Slavs for many generations. They later came under the rule of the Franks, Bulgaria, and Great Moravia. Some historians believe that Avar descendants who survived the Hungarian Conquest in the 890s were absorbed by the Hungarian population. The De Administrando Imperio, written around 950 AD, says that "there are still descendants of the Avars in Croatia, and are recognized as Avars." However, modern historians believe this statement refers to Avars in Pannonia, not Dalmatia. There's also a group called the Avar people of the Caucasus today, but most scholars doubt they are directly related to the historical Pannonian Avars.

Known Avar Leaders

The recorded Avar khagans (leaders) were:

- Kandik (around 552 - 562 AD)

- Bayan I (562—602 AD)

- Bayan II (602—617 AD)

- Bayan III (617—630 AD)

- Kouver Chagan (677-?)

- Theodorus (795—805 AD)

- Abraham (805—?)

- Isaac (?—835 AD)

Avar Society and Tribes

The Pannonian Basin was the heart of the Avar empire. The Avars moved people they captured from the edges of their empire to more central areas. Avar cultural items are found as far south as Macedonia. But east of the Carpathian mountains, there are almost no Avar archaeological finds. This suggests they lived mainly in the western Balkans. Experts believe the Avar society was very organized and had a clear hierarchy. They had complex relationships with other groups. The Khagan was the most important leader. He was surrounded by a small group of nomadic nobles.

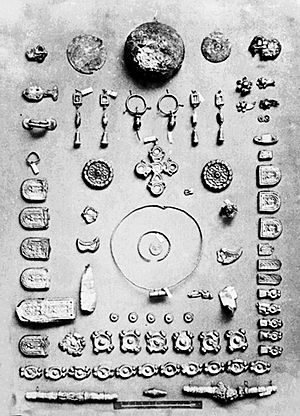

Some very rich burials have been found. These show that power was held by the Khagan and a small group of "elite warriors." These burials often included gold coins, decorated belts, weapons, and stirrups (footrests for riding horses) similar to those from Central Asia. Their horses were also buried with them. The Avar army was made up of many different groups. These included Slavic, Gepidic, and Bulgar fighters. There were also semi-independent "client" tribes, mostly Slavic. These tribes played important roles, like making diversionary attacks and guarding the Avars' western borders against the Frankish Empire.

At first, the Avars and the people they ruled lived separately. The only exceptions were Slavic and Germanic women who married Avar men. Over time, Germanic and Slavic people became part of the Avar social order and culture. This culture had influences from Persian and Byzantine styles. Scholars have found a mixed Avar-Slavic culture. This is seen in ornaments like half-moon earrings, Byzantine-style buckles, and bracelets. One historian noted that a mixed Slavic-Avar culture appeared in the 600s. This suggests peaceful relations between Avar warriors and Slavic farmers. It's possible that some Slavic tribal leaders became part of the Avar nobility. A few graves of Carolingian people (from the Frankish Empire) have also been found in Avar lands. They might have been hired fighters.

What Language Did the Avars Speak?

The language or languages spoken by the Avars are not fully known. Some experts believe that most Avar words found in old Latin or Greek texts might come from Mongolian or Turkic. Other theories suggest a Tungusic origin. Many of the titles and ranks used by the Pannonian Avars were also used by Turks, Bulgars, and Mongols. These include khagan, khan, kapkhan, tudun, tarkhan, and khatun.

However, there is also evidence that different groups within the Avar empire spoke different languages. Some scholars suggest Proto-Slavic became the common language of the Avar Khaganate. Other ideas include Caucasian, Iranian, Tungusic, and Hungarian. Based on archaeological and language information, some experts believe there is no strong evidence for Turkic or Mongolic languages among the Avars. Instead, they find evidence for Iranian languages, supported by Iranian words in local Slavic languages.

How the Avars Fought

The Avars were skilled warriors who fought almost entirely on horseback. They often used light horse archers. These archers had powerful composite bows. They wore little to no armor, sometimes just helmets or knee guards. The Avars also had heavy cavalry. These riders wore full armor, like chainmail or scale armor, and helmets. They carried long lances, swords, and daggers.

After taking control of the Slavic tribes in Pannonia, the Avars often teamed up with them. They used the Slavs as foot soldiers. Together, they even attacked Constantinople with many Persians. These Slavic warriors usually had bows, axes, spears, and round shields.

The Byzantine Emperor Maurice wrote about the Avars in his book Strategikon:

"They pay special attention to training in archery on horseback. A huge herd of male and female horses follows them. This provides food and makes their army look very big. They do not set up camps with fences, like the Persians and Romans [Byzantines]. Instead, until the day of battle, they spread out by tribes and clans. They continuously graze their horses in summer and winter... Also, in battle, when they face foot soldiers in a tight group, they stay on their horses and do not get off. They don't fight well on foot for long. They have been raised on horseback, and because they don't practice walking, they simply cannot walk around on their own feet..."-Maurice

Avar-Hungarian Connection Theory

Historian Gyula László suggested that many Avars who arrived in the Khaganate around 670 AD survived the Frankish attacks (791–795 AD). They lived through this period until the Magyars (Hungarians) arrived in 895 AD. László pointed out that the Hungarian settlements did not replace Avar ones. Instead, they filled in the gaps. Avars stayed on the good farming lands, while Hungarians took the river banks, which were good for grazing animals.

He also noted that Hungarian graveyards usually have 40–50 graves. Avar graveyards, however, have 600–1,000 graves. This suggests that the Avars not only survived but were much more numerous than the Hungarian conquerors. He also showed that Hungarians only settled in the center of the Carpathian Basin. Avars lived in a larger area. In areas where only Avars lived, the geographical names are Hungarian, not Slavic or Turkic. This is more evidence for a connection between Avars and Hungarians.

The names of Hungarian tribes, leaders, and titles suggest that at least the leaders of the Hungarian conquerors spoke Turkic. However, Hungarian is a Uralic language, not Turkic. So, it's possible that the Turkic-speaking Hungarian leaders were absorbed by the more numerous Avars.

László's theory suggests that the modern Hungarian language comes from the language spoken by the Avars, not the conquering Magyars. DNA evidence from graves shows that the original Magyars were most similar to modern Bashkirs, a Turkic people near the Ural mountains. The Khanty and Mansi people, whose languages are most similar to Hungarian, live northeast of the Bashkirs.

See also

In Spanish: Pueblo ávaro para niños

In Spanish: Pueblo ávaro para niños

- Keszthely culture

- Treasure of Nagyszentmiklós

- Pannonian Romance

- Székelys

- Palóc People

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |