Great Moravia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Great Moravia

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 833–c. 907 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A reconstructed banner (vexillum) based on a 9th-century image, with red-purple being the most likely color.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

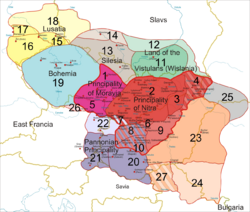

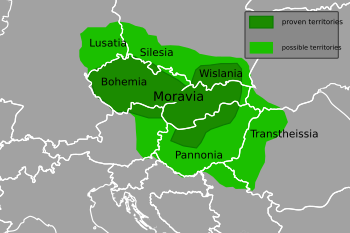

Great Moravia in the late 9th century

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Veligrad | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Slavic Old Church Slavonic Latin (religious) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Slavic Christianity Latin Christianity Slavic paganism |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy (principality) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| kъnendzь or vladyka | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• c. 820/830

|

Mojmír I (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 846

|

Rastislav | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 870

|

Svatopluk I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

833 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Decline and fall

|

c. 907 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Great Moravia was the first large state mainly made up of West Slavs. It grew in Central Europe around the 9th century. Today, parts of its territory are in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Austria, Germany, Poland, and other countries. Before Great Moravia, there was Samo's Empire and the Avar state in this region.

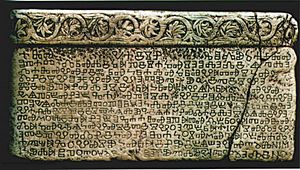

The main part of Great Moravia was in the area now called Moravia, in the eastern Czech Republic. This region is named after the Morava River. Great Moravia was important because it saw the start of the first Slavic literary culture. This culture used the Old Church Slavonic language. Christianity also spread here, first from missionaries from East Francia. Later, Saints Cyril and Methodius arrived in 863. They created the Glagolitic alphabet, which was the first alphabet for a Slavic language. A simpler alphabet called Cyrillic later replaced Glagolitic.

Great Moravia was largest under Prince Svatopluk I, who ruled from 870 to 894. After Svatopluk's death, the state began to weaken due to internal conflicts. It was eventually taken over by the Hungarians between 902 and 907.

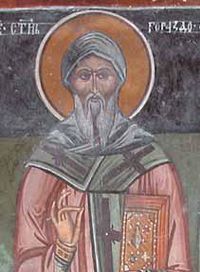

Under King Rastislav, Great Moravia saw big cultural changes. In 863, he asked the Byzantine emperor for a "teacher" to bring literacy and a legal system. This led to the arrival of Saints Cyril and Methodius. They introduced the Glagolitic alphabet and a Slavonic church service. This service was later approved by Pope Adrian II. The Glagolitic script was likely invented by Cyril. The language they used for translations was based on the Slavic dialect from their home city of Thessaloniki.

Later, King Svatopluk I expelled Cyril and Methodius's students. He wanted to focus on Western Christianity. However, these students spread their knowledge to other countries, especially in Southeastern Europe and Eastern Europe. In the First Bulgarian Empire, they continued the mission. Old Church Slavonic became an official written language in Bulgaria around 893. The Cyrillic alphabet was developed in Bulgaria and became official around 893. Cyrillic script and translated church services spread to other Slavic countries. This shaped their cultural development and led to the Cyrillic alphabets used today.

Saints Cyril and Methodius were named co-patrons of Europe by Pope John Paul II in 1980.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The Name "Great Moravia"

The meaning of "Great Moravia" has been discussed by historians. The name Megale Moravia (meaning "Great Moravia" in Greek) comes from a book written around 950 by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos. Some think the word "great" might have meant "old" instead. Another idea is that "great" referred to a territory outside the Byzantine Empire's borders. One historian, Lubomír E. Havlík, suggests that Byzantine scholars used this word for the homelands of nomadic peoples, like "Great Bulgaria."

The emperor's book is the only source from that time that uses "great" with Moravia. Other documents from the 9th and 10th centuries simply called it "Moravian realm" or "realm of Moravians." They also used names like "realm of Slavs" or "realm of Rastislav" or "realm of Svatopluk."

Where Did the Name "Morava" Come From?

"Morava" is the Czech and Slovak name for both the river and the country. It's believed the country was named after the river. The ending "-ava" is common in Czech and Slovak river names. It might come from an old Germanic word for "water." Some scholars link it to older Indo-European words meaning "water" or "sea." You can compare it to other river names like Mur in Austria or another Morava in Serbia.

Where Was Great Moravia?

After Great Moravia fell, its central lands were divided between the new Kingdom of Bohemia and the Hungarian Kingdom. The border was first along the Morava River. Over time, Czech kings gained more land on the eastern side.

The original heartland of Great Moravia is now in the eastern part of Moravia. It's between the White Carpathians and the Chřiby mountains. This area is called "Slovácko," which shows its shared history with neighboring Slovakia. This core region has a unique culture and rich folklore. It stretches south into two regions: Záluží on the Czech side of the Morava River and Záhorie on the Slovak side. Záhorie has the only building still standing from Great Moravian times: the chapel at Kopčany. This chapel is right across the Morava from the important archaeological site of Mikulčice.

Great Moravia expanded in the early 830s when Mojmír I conquered the nearby Principality of Nitra (now western Slovakia). The Principality of Nitra was often given to the future ruler, usually the ruling prince's nephew.

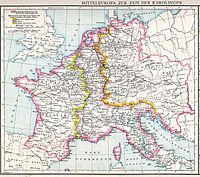

The exact size and even the location of Great Moravia are still debated. Some theories place its center south of the Danube River, in modern Serbia. Others suggest it was on the Great Hungarian Plain. The exact date it was founded is also unclear, but it was likely in the early 830s under Prince Mojmír I. Mojmír and his successor, Rastislav, first accepted the rule of the Carolingian kings. But Moravia's fight for independence led to many conflicts with East Francia from the 840s.

The Most Common View

Most historians believe Great Moravia's main lands were in the valley of the Morava River. This is in what is now the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Digs have found large early medieval forts and many settlements. This suggests an important power center grew here in the 9th century. Old writings also support this view. For example, Alfred the Great's translation of History of the World mentions Moravia's neighbors. Also, the story of Cyril and Methodius traveling from Moravia to Venice through Pannonia supports it.

The exact borders of Moravia are hard to know because old sources aren't very precise. For example, monks writing the Annals of Fulda in the 9th century didn't know much about Central European geography. Also, Moravian rulers kept expanding their territory in the 830s, so the borders changed often.

Moravia was largest under Svatopluk I (870–894). Regions like Lesser Poland and Pannonia had to accept his rule, at least for a short time. However, shared cultural zones found by archaeologists don't prove that these northern areas were always part of Moravia. Some scholars warn that it's wrong to draw exact borders for the core lands. They say Moravia hadn't developed to that level yet.

A Look at History

Early Times (Before 800 AD)

The first possible mention of Slavic tribes in the northern Morava river valley comes from the Byzantine historian Procopius. He wrote about Germanic people passing through "Sclavenes" territory in 512. Archaeological sites show handmade pottery from around 550 AD.

After 568, nomadic Avars from the Eurasian Steppes conquered large areas in the Pannonian Basin. Slavs had to pay tribute to the Avars and join their raids. Over time, Avars started to settle down and live alongside the local Slavs.

In the 7th and 8th centuries, the local Slavs developed quickly. The first Slavic fortified settlements were built in Moravia in the late 7th century. A new social group, warrior horsemen, appeared in Moravia, Slovakia, and Bohemia from the late 7th century. More fortified settlements were built in the 8th century, showing continued social growth. In Moravia, these were mostly around the Morava River. In Slovakia, the oldest fortified settlements are from the late 8th century. They were in areas not directly controlled by the Avars.

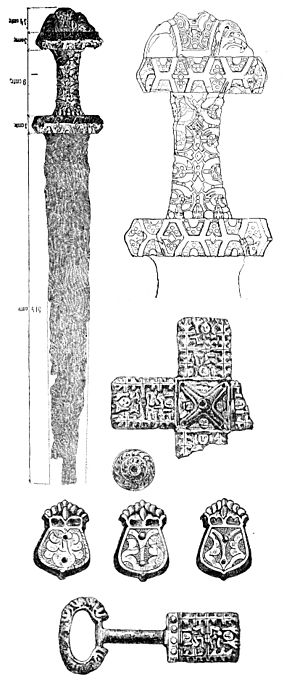

Charlemagne attacked the Avars in the late 8th century, causing the Avar Khaganate to collapse. After this, Frankish military gear became popular north of the Middle Danube. A new style of metalwork, called the "Blatnica-Mikulčice horizon," appeared. This style mixed Avar and Carolingian art. One famous item is a sword found in Blatnica, dated between 825 and 850. Some think it was made by a Frankish artisan, while others say Moravian craftsmen adapted Frankish styles.

Moravia Grows (800–846 AD)

Moravia, the first Western Slavic state, formed when Slavic tribes north of the Danube united. However, old writings don't say much about how it formed. The first mention of the Moravian state might be in 811. In that year, Avar rulers and Slavic leaders from along the Danube visited Emperor Louis the Pious's court. The first clear mention of Moravians was in 822. The emperor met with leaders from many East Slavic groups, including Moravians, at an assembly in Frankfurt.

A late 9th-century text, The Conversion of the Bavarians and the Carantanians, first mentions a Moravian ruler. It says Mojmír, "duke of the Moravians," expelled "one Pribina" across the Danube. Pribina then fled to Ratpot, who ruled the March of Pannonia from around 833. Historians debate if Pribina was an independent ruler or one of Mojmír's officials. Some say Mojmír and Pribina were both Moravian princes. Others say Pribina was Mojmír's helper in Nitra. Historians who see Pribina as an independent ruler say "Great Moravia" formed when Mojmír forced Pribina's Principality of Nitra to join Moravia.

A 9th-century list of forts north of the Danube mentions that the Moravians had 11 forts. It places them between the Bohemians and the Bulgars. It also mentions the Merehani and their 30 forts. Some historians think the Merehani were the people of the Principality of Nitra. Others believe the Merehani were another Moravia in Central Europe.

According to a 13th-century source, Bishop Reginhar of Passau baptized "all of the Moravians" in 831. We don't know much about this event. Some historians believe Mojmír was baptized then. However, other sources say Christian missionaries from Italy, Greece, and Germany were still arriving in Moravia in the 860s. They also say that missionaries from East Francia allowed pagan customs to continue for decades after 831.

Around August 15, 846, Louis the German, King of East Francia, attacked the "Moravian Slavs, who were planning to defect." The details are unclear. Some say Louis took advantage of internal problems after Mojmír's death. Others say Mojmír was captured and removed from power. What is clear is that Louis the German appointed Mojmír's nephew, Rastislav, as the new duke of Moravia during this campaign.

Fighting for Freedom (846–870 AD)

Rastislav (846–870) first accepted Louis the German's rule. But he soon made his own position stronger and expanded his lands. Some historians believe the state called "Great Moravia" by Constantine Porphyrogenitus really started to grow during Rastislav's rule.

Rastislav turned against East Francia and supported a rebellion against Louis the German in 853. The Frankish king invaded Moravia in 855. The Annals of Fulda says the Moravians were "defended by strong fortifications." The Franks left without defeating them, and fighting continued until a peace treaty in 859. This truce showed how strong Rastislav's realm was becoming. Conflicts continued for years. For example, Rastislav supported Louis the German's son, Carloman, in his rebellion in 861. The first record of Magyars (Hungarians) raiding Central Europe might be linked to these events. The Annals of St. Bertin says "enemies called Hungarians" attacked Louis the German's kingdom in 862. This suggests they helped Carloman.

Rastislav wanted to reduce the influence of Frankish priests, who served East Francia's interests. He first asked Pope Nicholas I in 861 to send missionaries who knew the Slavic language. When Rome didn't answer, Rastislav asked the Byzantine Emperor Michael III for the same. By connecting with Constantinople, he also wanted to counter an alliance between the Franks and Bulgarians. The emperor sent two brothers, Constantine and Methodius, to Moravia in 863. They spoke the Slavic dialect from their home in Thessaloniki. Constantine's story says he created the first Slavic alphabet and translated the Gospel into Old Church Slavonic around that time.

Louis the German invaded Moravia again in August 864. He surrounded Rastislav "in a certain city, which in the language of that people is called Dowina." The Franks couldn't take the fort, but Rastislav agreed to accept Louis the German's rule. However, he kept supporting the Frankish king's enemies.

The Byzantine brothers, Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius, visited Rome in 867. Pope Hadrian II approved their translations of church texts and ordained six of their students as priests. In 869, the pope told three Slavic rulers—Rastislav, his nephew Svatopluk, and Kocel (who ruled Pannonia)—that he approved using the local language in church services. In 869, Methodius was sent by the pope to Rastislav, Svatopluk, and Kocel. Methodius only visited Kocel, who sent him back to the pope. Hadrian then made Methodius an archbishop. Svatopluk was ruling what used to be the Principality of Nitra, under Rastislav. Frankish troops invaded both Rastislav's and Svatopluk's lands in August 869. The Annals of Fulda says the Franks destroyed many forts and took loot. But they couldn't take Rastislav's main fortress.

Svatopluk's Rule (870–894 AD)

Svatopluk joined forces with the Franks and helped them capture Rastislav in 870. Carloman took over Rastislav's realm and put two Frankish lords, William and Engelschalk, in charge. Frankish soldiers arrested Archbishop Methodius at the end of the year. Svatopluk, who still ruled his own lands, was accused of betrayal and arrested by Carloman in 871. The Moravians rebelled against the Frankish governors and chose Slavomír, a relative of Svatopluk, as their new duke. Svatopluk returned to Moravia, led the rebels, and drove the Franks out. Some historians say this rebellion in 871 led to the creation of the first Slavic state.

Louis the German sent his armies against Moravia in 872. The imperial troops looted the countryside but couldn't take the "extremely well-fortified stronghold" where Svatopluk was hiding. Svatopluk even gathered an army that defeated some imperial troops, forcing the Franks to leave Moravia. Svatopluk soon started talks with Louis the German, which ended with a peace treaty in May 874. At this meeting, Svatopluk's messenger promised that Svatopluk "would remain faithful" to Louis the German and pay a yearly tribute.

Meanwhile, Archbishop Methodius, released by Pope John VIII in 873, returned to Moravia. Methodius's story says that "Prince Svatopluk and all the Moravians" decided to give him control over "all the churches and clergy" in Moravia. Methodius continued translating religious texts. He translated "all the Scriptures in full, except Maccabees." However, Frankish priests in Moravia opposed the Slavic church service and even accused Methodius of heresy. Although the Pope never said Methodius was a heretic, in 880 he appointed Methodius's main opponent, Wiching, as bishop of Nitra. Svatopluk himself preferred the Latin church service.

A letter from around 900 mentions that the pope sent Wiching to a "newly baptized people" whom Svatopluk "had defeated in war and converted from paganism to Christianity." Other sources also show that Svatopluk greatly expanded his realm. For example, the Life of Methodius says Moravia "began to expand much more into all lands and to defeat its enemies successfully" after 874. The same source tells of a "very powerful pagan prince settled on the Vistula" in Poland. Svatopluk attacked and captured this prince.

In June 880, Pope John issued a special letter called a papal bull for Svatopluk. He called Svatopluk "glorious count" and "the only son" of the Holy See. This title was usually only used for emperors. The pope promised to protect the Moravian ruler, his officials, and his people. The bull also confirmed Methodius's role as the head of the church in Moravia. It gave him power over all clergy, including Frankish priests. Old Church Slavonic was recognized as the fourth liturgical language, along with Latin, Greek, and Hebrew.

The Annals of Salzburg mentions a raid by the Magyars and the Kabars in East Francia in 881. Some historians believe Svatopluk started this raid because his relationship with Arnulf, the son of King Carloman, was tense. Archbishop Theotmar of Salzburg clearly accused the Moravians of hiring "a large number of Hungarians" and sending them against East Francia.

During a civil war in Pannonia (882–884), Svatopluk "collected troops from all the Slav lands" and invaded Pannonia. The Bavarian Annals of Fulda says the Moravian invasion "laid waste" to Pannonia east of the Rába river. However, other sources say Arnulf of Carinthia kept control of Pannonia. Svatopluk met with Emperor Charles the Fat in 884. At this meeting, Svatopluk became the emperor's vassal and promised never to attack the emperor's realm.

Archbishop Methodius died on April 6, 885. His opponents, led by Bishop Wiching of Nitra, used his death to convince Pope Stephen V to limit the use of Old Church Slavonic in church services. Bishop Wiching even convinced Svatopluk to expel all of Methodius's students from Moravia in 886. This stopped the promising literary and cultural growth of Central European Slavs.

Pope Stephen's letter called Svatopluk "Svatopluk, King of the Slavs." This suggests Svatopluk was crowned king by the end of 885. Frankish records also sometimes called Svatopluk king during this time.

Moravia reached its largest size in the last years of Svatopluk's rule. King Arnulf of East Francia gave control of the Bohemians to Svatopluk in 890. Some historians believe Svatopluk also took over Silesia and Lusatia in the early 890s. In 892, King Arnulf wanted to meet Svatopluk, but Svatopluk refused and broke his promises. In response, Arnulf invaded Moravia in 892. He couldn't defeat Svatopluk, even with help from Magyar horsemen.

The End of Great Moravia (894–Before 907 AD)

Svatopluk, described as "a man most prudent among his people and very cunning," died in the summer of 894. His son, Mojmir II, took over. But the empire quickly fell apart. The tribes Svatopluk had conquered began to break free. For example, the Bohemian dukes accepted King Arnulf's rule in 895. Mojmír II tried to regain control over them but failed. However, he did manage to restore the Church in Moravia. He convinced Pope John IX to send his representatives to Moravia in 898. These representatives quickly appointed an archbishop and three bishops in Moravia.

Conflicts between Mojmír II and his younger brother, Svatopluk II, gave King Arnulf a reason to send troops to Moravia in 898 and 899. The Annals of Fulda says that Svatopluk II was rescued by Bavarian forces from prison in 899. Some historians believe Svatopluk II had inherited the "Principality of Nitra" from his father. They say the Bavarians destroyed the fortress at Nitra then.

Most sources from that time say the Hungarians played a big role in Great Moravia's fall. For example, one writer says Svatopluk I's "sons held his kingdom for a short and unhappy time, because the Hungarians utterly destroyed everything in it." The Hungarians began conquering the Carpathian Basin around 895.

A letter from around 900 shows that Moravians and Bavarians accused each other of making alliances with the Hungarians. One writer, Liudprand of Cremona, says the Hungarians "claimed for themselves the nation of the Moravians" in 900. Another source says a large Hungarian army "attacked and invaded" the Moravians in 900. Facing more Hungarian attacks, Mojmír II made a peace treaty with Louis the Child in 901.

We don't know the exact year Great Moravia ended because there aren't enough documents. Some say it was 902, others 903 or 904, and some say 907. A trade regulation from 903–906 still mentions "markets of the Moravians," suggesting Moravia still existed then. It's clear that no Moravian forces fought in the Battle of Pressburg in 907, where the Hungarians defeated a large Bavarian army.

How Great Moravia Was Organized

Sources of Information

Writings from the 9th century tell us very little about how Great Moravia worked internally. Only two legal texts have survived: the Nomocanon (a collection of Byzantine church laws) and the Court Law for the People (based on an 8th-century Byzantine law code). Methodius finished both of these shortly before his death in 885.

Besides old chronicles and documents, archaeological digs have helped us understand the Moravian state and society. Important Moravian sites like Mikulčice, Pohansko, and Staré Město were dug up in the 1950s and 1960s. However, there's still a lot of information from these digs that needs to be fully studied.

How Settlements Were Built

The main parts of Great Moravian settlements were well-protected forts. These were built by local Slavs on high places and in lowlands like marshes or river islands. Most Great Moravian castles were large hill forts. They were protected by wooden fences, stone walls, and sometimes moats. The typical Moravian walls combined an outer stone wall with an inner wooden structure filled with earth. The forts usually had several connected areas. Important buildings were in the center, and workshops were in the outer areas. Most buildings were made of wood, but churches and homes were made of stone. Often, old forts from prehistoric times were also used. Great Moravian towns, especially in Moravia and Slovakia's lowlands, were often far from stone quarries. Materials had to be moved many kilometers.

Great Moravian settlements fall into four main types. The most important were central places like Mikulčice-Valy, Staré Město – Uherské Hradiště, and Nitra. Here, several castles and settlements formed a huge fortified city-like area. Besides these main centers, there were fortified regional centers, forts mainly for defense, and refuge forts used only in times of danger. The largest forts were usually protected by a chain of smaller ones. Smaller forts also protected trade routes and offered shelter for farmers during attacks. Noble courts, like in Ducové, also existed. They were probably inspired by Carolingian estates.

In 9th-century Mikulčice, the main fortified area was on an island in the Morava River. It was surrounded by a stone wall that covered six hectares. A large unfortified settlement of 200 hectares was outside the walls. The exact location of the Great Moravian capital, "Veligrad," is unknown. But Mikulčice, with its palace and 12 churches, is the most likely candidate. Another important settlement was a large area in Pohansko near Břeclav. Nitra, the center of the eastern part of the empire, was ruled by the heir to the throne. Nitra had several large fortified settlements with different purposes. It also had about twenty specialized craft villages, making it a true metropolis. Crafts included luxury items like jewelry and glass. Many smaller forts surrounded this area.

Bratislava Castle had a stone two-story palace and a large three-nave church, built in the mid-9th century. Digs at the cemetery near the church found Great Moravian jewelry, similar to those from Mikulčice. The castle's name was first recorded in 907 as Brezalauspurc. This name might mean "Predslav's Castle" (after a son of Svatopluk I) or "Braslav's Castle" (after Braslav of Pannonia). Several fortified settlements were found in Slovak Bojná, with important Christian artifacts. Many castles were built on hills around the Váh and Nitra rivers, and in other areas.

The strong Devín Castle, near Bratislava, protected Great Moravia from attacks from the West. Some say it was built later by Hungarian kings. But digs have found an older Slavic fortified settlement from the 8th century. During the Great Moravian period, Devín Castle was home to a local lord. His followers were buried around a stone Christian church. These two castles were supported by smaller forts nearby. Another example is the fortress at Thunau am Kamp in Lower Austria. Its defenses reused old Bronze Age earthworks and were almost as big as the Frankish Emperor's capital of Regensburg.

The number of forts found is more than what old writings mention (11 centers for Moravians and 30 for "other Moravians"). The only castles named in texts are Nitrawa (828; Nitra), Dowina (864; possibly Devín Castle), and maybe Brezalauspurc (907; possibly Bratislava Castle). Some sources also claim Uzhhorod in Ukraine (903) was a Moravian fortress.

Rulers of Great Moravia

Great Moravia was ruled by kings from the House of Mojmir. The throne rarely passed from father to son. Svatopluk I was the only ruler whose son took over after him. Rastislav became king because the East Frankish king intervened. Slavomir was chosen as duke when the Franks captured Svatopluk in 871. This shows how strong the Mojmir family's claim to the throne was, as Slavomir was a priest when he was chosen. Moravian rulers were usually called dukes, but sometimes kings in 9th-century documents. Tombs inside a church have only been found at Mikulčice. This suggests that only royals had the special right to be buried in such an important place.

How the State Was Run

The Annals of Fulda never calls Moravian rulers heads of a state. Instead, it calls them heads of a people, like "duke of the Moravians." This suggests that Great Moravia was not mainly organized by land areas. It was more likely based on family ties within tribal groups. However, other historians say Moravia was divided into counties, each led by rich and noblemen. They say the number of counties grew from 11 to 30 by the second half of the 9th century. The existence of scattered groups of warrior-farmers suggests there were administrative units. Without such a system, the rulers couldn't organize their military campaigns.

Svatopluk added many Slavic tribes (like the Bohemians and Vistulans) to his empire. These conquered tribes were ruled by vassal princes or governors. But they kept some independence. This contributed to Great Moravia's quick breakup after Svatopluk's death.

Some historians believe Great Moravia had two main centers. They suggest that terms like "Moravian lands" and "Upper Moravias" refer to a dual organization of the state. This included the "Realm of Rastislav" (modern Moravia in the Czech Republic) and the "Realm of Svatopluk" (the Principality of Nitra in Slovakia). However, not everyone agrees with this view.

Warfare and the Army

Old writings mention about 65 events related to warfare in Great Moravia. The most detailed records are from Frankish sources during Svatopluk's rule. The Great Moravian army was mainly based on an early feudal system. Military service was mostly done by the ruling class.

The core of the Great Moravian army was a prince's personal guard of professional warriors, called družina. They collected tribute and punished wrongdoers. The družina included noblemen ("older retinue") and younger military groups ("younger retinue"). Some were permanent guards for the prince. The rest were stationed at forts or important locations. This družina was likely loyal and supported the prince, as there are no records of them being unhappy or rebelling. The permanent army was mainly cavalry. Great Moravian heavy cavalry copied Frankish knights. They used expensive equipment that only the richest people could afford. An Arab traveler noted that Svatopluk I had many cavalry horses. The total size of the družina is estimated at 3,000–5,000 men. For larger mobilizations, cavalry was joined by smaller units from local nobles and communities.

The second part of the army consisted of free citizens who were not professional warriors. They were important for defending Great Moravian territory. Their participation in wars of expansion was less common. The army was led by the prince or a commander-in-chief called a voivode. The army's maximum size is estimated at 20,000–30,000 men. Ordinary people helped defend and distract enemies during attacks. A key part of Great Moravia's defense was its strong forts. These were hard to attack with the military methods of the time. A Frankish writer was amazed by the size of Rastislav's fortress.

A common weapon for a West Slavic foot soldier was a specific type of axe called a bradatica. Spears were used by both foot soldiers and cavalry. Weapons linked to nomadic cultures, like sabres and specific bows, are missing. Instead, military equipment was more influenced by Western types. New weapons like double-edged swords became popular. Archers were part of the infantry.

Noble Families

The existence of a local noble class is well documented. Old sources mention "leading men" or "nobles." However, these documents don't explain how these Moravian chiefs gained their power. Richly decorated graves have only been found in Mikulčice and other large forts controlled by the rulers. This suggests that being close to the ruler, who traveled between centers, was the best way for the top elite to gain wealth. The nobles also had an important role in government. Rulers didn't make big decisions without discussing them in a council of Moravian "dukes."

The People of Great Moravia

Great Moravia was home to the West Slavs, a subgroup of the larger Slavic people. West Slavs came from early Slavic tribes who settled in Central Europe after Germanic tribes left. They "absorbed the remaining Celtic and Germanic populations" in the area.

Moravians had strong cultural ties to their western neighbors, the Franks. Many objects show Carolingian influence. Archaeological evidence shows that the material culture in modern Moravia in the 9th century was very much like Frankish culture, with little Byzantine influence.

Carolingian influence affected all parts of life in Great Moravia. After the Carolingian Empire split, the Ottonian dynasty continued these traditions. It's not a coincidence that new medieval West Slavic states borrowed from Carolingian traditions through the Ottonian Empire.

Most of the population were free people who had to pay a yearly tax. Slavery and feudal dependency also existed.

Studies of early medieval cemeteries in Moravia show that 40 percent of men and 60 percent of women died before age 40. More than 40 percent of graves contained children aged one to twelve. However, the cemeteries also show that people had good nutrition and advanced health care. For example, a third of the skeletons had no caries (cavities) or lost teeth, and bone fractures healed well.

Economy and Trade

The large 9th-century forts found at Mikulčice and other places were near where the Morava and Danube rivers meet. Two important trade routes crossed this region: the Danube River and the old Amber Road. This means these settlements, all on rivers, were important trade centers. Finds of tools, raw materials, and partly finished goods show that craftsmen lived in these settlements. The large forts were surrounded by small villages where people farmed. They grew wheat, barley, millet, and other cereals. They also raised cattle, pigs, sheep, and horses. Their animals were quite small, like modern Przewalski horses.

We don't have proof of a general currency in Moravia. There are no local coins, and foreign coins are rare. Some archaeologists believe axe-shaped metal bars found in forts were used as "pre-money." But this idea isn't accepted by everyone, as these objects might have been raw materials for other products. The lack of coins meant Moravian rulers couldn't easily collect taxes, customs, and fines. This weakened their position internationally.

Iron working and smithing were the most important local industries. For example, they made very good asymmetrical plowshares. There are no signs of silver, gold, copper, or lead mines in Moravia. But jewelry and weapons were made locally. This means their main materials were gained from raids, gifts, or brought by merchants. Archaeological research also shows that luxury goods were imported, including silk, brocade, and glass vessels. Some historians believe Moravians mainly traded slaves, taken as prisoners of war during raids, for these luxury goods. For example, Archbishop Thietmar of Salzburg accused Moravians of "bringing noble men and honest women into slavery" during their campaigns. Slave trading is also well documented. One story says many of Methodius's students "were sold for money to the Jews" after 885. A trade regulation also mentions slaves being sent from Moravia to the west.

Culture and Art

Church Buildings

Ideas about Great Moravian church architecture changed a lot in the second half of the 20th century. At first, people thought there were only simple wooden churches. But after digs in Staré Město in 1949, this changed. From the 1960s, stone churches were also found in Slovakia. By 2014, over 25 church buildings have been confirmed in the main area of Great Moravia (Moravia and Western Slovakia). Some of the first churches found were just "negatives" (ditches where foundations used to be). But later digs found actual foundations. After Great Moravian graves were found near the church in Kopčany, the idea that several standing churches in Slovakia are from Great Moravia became popular again. Scientists are still trying to find exact dates using methods like radiocarbon analysis.

Great Moravian church architecture shows many different styles. These include three-nave basilicas, triconcha (three-lobed buildings), and various types of rotundas (round buildings) with one or more apses (rounded ends). Most churches have been found in southeastern Moravia. Mikulčice stands out with twelve churches. Its first stone churches were built around 800. The three-nave basilica from Mikulčice is the largest church found so far. It is 35 meters by 9 meters and has a separate baptistery (a place for baptisms). The high number of churches in Mikulčice was more than the local people needed. So, they are believed to be private churches, like those in Francia. Large churches were also important church centers. The current dating of several churches is earlier than the Byzantine mission. The churches were mostly decorated with frescoes (paintings on wet plaster). The artists were probably from Francia and northern Italy.

Great Moravian church architecture was likely influenced by Frankish, Dalmatian-Istrian, Byzantine, and classical styles. This shows that many different missionary groups were active. Two open-air museums, in Modrá near Uherské Hradiště and in Ducové, are dedicated to Great Moravian architecture.

Religion and Beliefs

Like other Slavs, the Great Moravian Slavs originally believed in many gods and honored their ancestors. Several pagan worship sites from before the Christianization of Moravia have been found in Moravia (Mikulčice and Pohansko). We don't know what these objects, like a ring ditch with a fire or animal sacrifices, meant to them. One supposed pagan shrine in Mikulčice was reportedly used until the Moravian elite became Christian in the mid-9th century. Idols in Pohansko were put up where a church had been destroyed during a pagan reaction in the 10th century. The only Slavic pagan shrine found in modern Slovakia is in Most pri Bratislave. It was probably dedicated to Perun, the god of war and thunder. This shrine was abandoned in the mid-9th century.

The spread of Christianity happened in several steps and is still being studied. In older books, the first organized missions were often linked to Irish and Scottish missionaries. But modern studies are more doubtful about their direct impact. Great Moravia was first Christianized by missionaries from the Frankish Empire or Byzantine areas in Italy and Dalmatia. This started in the early 8th century, and sometimes even earlier. Signs of missions from Aquileia-Dalmatia are found in Great Moravian buildings and language. Italian influence is also thought to be behind golden plaques with Christian symbols from Bojná. These are important Christian artifacts from before the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius.

After the Avars were defeated in the late 8th century, Frankish missionaries became very important. The first Christian church of the Western and Eastern Slavs mentioned in writings was built in 828 by Pribina in Nitra. Bishop Adalram of Salzburg consecrated it. Most of the area was Christianized by the mid-9th century. Even though the leaders formally accepted Christianity, Great Moravian Christianity still had many pagan elements as late as 852. For example, grave goods like food could be found even in church graveyards. The Church in Great Moravia was overseen by Bavarian clergy until the Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius arrived in 863.

In 880, the pope made a monk named Wiching bishop of the new see of Nitra. Some experts say the location of this 9th-century diocese was different from today's Nitra.

Writing and Books

The work of Cyril and Methodius had a huge impact beyond religion and politics. Old Church Slavonic became the fourth official language for church services in the Christian world. However, after Methodius died in 885, all his followers were expelled from Great Moravia. So, the use of Slavic church services in Great Moravia lasted only about 22 years. Its later form is still used in the church services of the Ukrainian, Russian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbian, and Polish Orthodox Churches. Cyril also invented the Glagolitic alphabet, which was good for Slavic languages. He and Methodius were the first to translate the Bible into a Slavic language.

Methodius wrote the first Slavic legal code. It combined local customary law with advanced Byzantine law. Church law was simply taken from Byzantine sources.

Not many literary works can be clearly identified as originally written in Great Moravia. One is Proglas, a poem where Cyril defends the Slavic church service. Vita Cyrilli and Vita Methodii are biographies that give valuable information about Great Moravia under Rastislav and Svatopluk I.

The brothers also founded an academy, first led by Methodius. It trained hundreds of Slavic priests. A well-educated class was vital for running any early feudal state, and Great Moravia was no different. Vita Methodii mentions that the bishop of Nitra served as Svatopluk I's chancellor. Even Prince Koceľ was said to have mastered the Glagolitic script. The location of the Great Moravian academy is unknown. Possible sites include Mikulčice, Devín Castle, and Nitra. When Methodius's students were expelled from Great Moravia in 885, they spread their knowledge (including the Glagolitic script) to other Slavic countries like Bulgaria, Croatia, and Bohemia. They created the Cyrillic script, which became the main alphabet in the Kievan Rus' (modern Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus). Great Moravian culture continued in Bulgarian seminaries, preparing the way for the Christianization of Kievan Rus'.

The cultural mission of Cyril and Methodius greatly influenced most Slavic languages. It was the beginning of the modern Cyrillic alphabet. This alphabet was created in the 9th century in Bulgaria by Bulgarian students of Cyril and Methodius.

Art and Craftsmanship

In the first half of the 9th century, Great Moravian craftsmen were inspired by Carolingian art. In the second half of the 9th century, Great Moravian jewelry was influenced by Byzantine, Eastern Mediterranean, and Adriatic styles. However, as Czech archaeologist Josef Poulík said, "these new forms and techniques were not copied passively." Instead, they were changed to fit the local style, creating a unique Great Moravian jewelry style. Typical Great Moravian jewelry included silver and gold earrings decorated with fine granular filigree. They also made silver and gilded bronze buttons with leaf designs.

What Happened Next?

Great Moravian centers like Bratislava, Nitra, Tekov, and Zemplín continued to be important after Great Moravia fell. However, some historians debate if Bratislava, Tekov, and Zemplín were truly Great Moravian castles. Some sources suggest that Hungarian rulers used German or Bulgar models when setting up their new administrative system.

Social differences in Great Moravia reached an early stage of feudalism. This created the social base for later medieval states in the region. What happened to Great Moravian noble families after 907 is still debated. Recent research suggests that many local nobles were not greatly affected by the fall of Great Moravia. Their descendants became nobles in the new Kingdom of Hungary. The most famous examples are the powerful Hunt and Pázmán families. However, other old writings say that the important noble families of Hungary came from Magyar leaders or immigrants, not from Great Moravia. For example, the ancestors of the Hunt-Pázmán clan, who some Slovak scholars say were of Great Moravian origin, were reported to have arrived from the Duchy of Swabia in the late 10th century.

The territories called "one-third part of the Kingdom of Hungary" in medieval sources are called the "Duchy" in Hungarian studies and the "Principality of Nitra" in Slovak studies. These areas were ruled independently by members of the Árpád dynasty (the Hungarian ruling family). This practice was similar to the Great Moravian system of giving land to the heir to the throne. The existence of an independent political unit around Nitra is often seen by Slovak scholars as a sign of continued political life from the Great Moravian period.

Great Moravia also became a big theme in Czech and Slovak romantic nationalism in the 19th century. The Byzantine double-cross, believed to have been brought by Cyril and Methodius, is now part of the symbol of Slovakia. The Constitution of Slovakia mentions Great Moravia in its introduction. Interest in this period grew during the national revival in the 19th century. Great Moravian history has been seen as a cultural root for several Slavic nations in Central Europe. It was used to try and create a single Czechoslovak identity in the 20th century.

Although some sources say Great Moravia disappeared without a trace, archaeological research and place names suggest that Slavic people continued to live in the valleys of the Inner Western Carpathians. Also, there are occasional mentions of Great Moravia from later years. In 924/925, two writers mentioned Great Moravia. In 942, Magyar warriors captured during a raid said that Moravia was their northern neighbor. The fate of the northern and western parts of former Central Europe in the 10th century is still largely unclear.

The eastern part of Great Moravia (present-day Slovakia) came under the rule of the Hungarian Árpád dynasty. The northwest borders of the Principality of Hungary became mostly empty or sparsely populated land. This was a border region that lasted until the mid-13th century. The rest of the land stayed under the rule of local Slavic nobles. It was slowly integrated into the Kingdom of Hungary, a process finished in the 14th century. In 1000 or 1001, all of present-day Slovakia was taken over by Poland under Bolesław I. Much of this territory became part of the Kingdom of Hungary by 1031.

See also

In Spanish: Gran Moravia para niños

In Spanish: Gran Moravia para niños

- History of Moravia

- History of Slovakia

- History of the Czech lands

- Slavs in Lower Pannonia

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |