History of the Czech lands facts for kids

The history of the Czech lands – the area we now call the Czech Republic – began about 800,000 years ago! The very first simple stone tool was found near Brno. Many ancient cultures lived here during the Stone Age, which ended around 2000 BCE. One important culture was the Únětice Culture, known for about 500 years at the end of the Stone Age and beginning of the Bronze Age.

The first people we know by name were the Celts, who arrived around 500 BCE. One Celtic tribe, the Boii, gave the Czech lands their first name: Boiohaemum, which means the Land of the Boii. Before the Common Era began, Germanic tribes mostly pushed the Celts out. The Marcomanni were a famous Germanic tribe, and signs of their wars with the Roman Empire can still be found in south Moravia.

After a time of big migrations, Slavic tribes settled the Czech lands. In 623, the first known state formed when Samo united local Slavic tribes. He defended them from the Avars and later won a battle against the Franks. After Samo's state ended, the Great Moravia kingdom appeared. Its main power was in Moravia and today's western Slovakia. In 863, Cyril and Methodius, two scholars from Greece, brought Christianity and the first Slavic alphabet, Glagolitsa, to Great Moravia. The kingdom fell apart during the Magyar invasion in the early 900s.

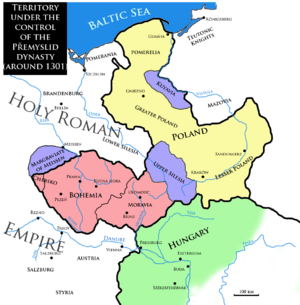

A new state grew around the Premyslids tribe, forming the Duchy of Bohemia. This duchy was strongly connected to the Holy Roman Empire. In 1212, Duke Ottokar I became a hereditary king. The Přemyslid family line ended in the early 1300s and was replaced by the Luxembourg dynasty. The most famous Luxembourg ruler was Charles IV, who became the Holy Roman Emperor. He started the Archbishopric of Prague and Charles University, the first university north of the Alps and east of Paris.

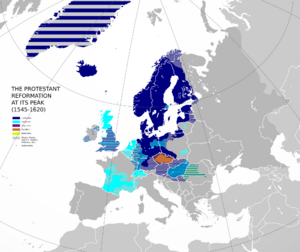

In the early 1400s, ideas similar to Protestantism began to spread in the Czech lands. When Jan Hus was executed, it started the Hussite Wars and a big religious split. The Jagiellon dynasty took the Czech throne in 1471. They ruled for 50 years until King Louis Jagiellon died in the Battle of Mohács. The empty throne then went to the House of Habsburg.

After Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg died, religious and political tensions grew. This led to the Second Defenestration of Prague, which started the Thirty Years War. Many Czech nobles who supported the Protestant side lost their lands. The Czech lands then saw more German influence and a return to Catholicism. In the late 1700s, Romanticism helped spark the Czech National Revival. After 1848, Czech leaders worked harder to gain more freedom for the Czech lands within the Habsburg Monarchy.

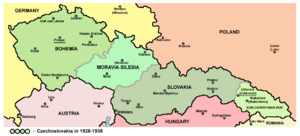

World War I offered a chance for full independence. In 1915, Czech and Slovak leaders agreed to create a shared state. After Austria-Hungary surrendered in 1918, the Czechoslovak Republic was born. This "First Republic" lasted 20 years until World War II. After World War II, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia took power in 1948, and Czechoslovakia joined the Eastern Bloc. In August 1968, Warsaw Pact armies invaded to stop reforms. In November 1989, the Velvet Revolution peacefully ended Communist rule, creating the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic. Three years later, Czech and Slovak leaders agreed to split into separate countries. In 1999, the Czech Republic joined NATO, and in 2004, it became part of the European Union.

Contents

Ancient Times: Early Humans and Tribes

Stone Age: First People and Discoveries

A simple stone tool, made by early human ancestors, was found in Red Hill in Brno. It is about 800,000 years old. The first signs of human camps were found near Prague and Brno, dating back about 600,000 years ago.

Stone tools from 120,000 years ago were found in the Kůlna Cave in central Moravia. Even older stone tools and bones of a Neanderthal man were found there, from about 50,000 years ago.

Human bones from 45,000 years ago were discovered in the Koněprusy Caves. Bones from 30,000 BCE were found in the Mladeč caves. Huge mammoth tusks with detailed carvings (also around 30,000 BCE) were found in Pavlov and Předmostí. This makes south Moravia a very important archaeological area in Europe.

The site at Předmostí has the largest collection of human remains from the Gravettian culture. This culture was famous for making small statues called Venus figurines. One of the most famous is the Venus of Dolní Věstonice (29,000–25,000 BCE), found in Dolní Věstonice. Another, the Venus of Petřkovice, was found in what is now Ostrava. Remains of mammoth hunters from 22,000 BCE were also found in Kůlna Cave. Later, reindeer and horse hunters lived there around 10,000 years later.

Between 5500 and 4500 BCE, people of the Linear Pottery culture lived in the Czech lands. Their settlement was found near Kutná Hora. Other cultures like the Lengyel culture and Funnelbeaker culture followed them.

Copper and Bronze Ages: New Cultures

During the Copper Age, the Corded Ware culture was in the north and the Baden culture in the south. The Bell Beaker culture marked the change from the Copper Age to the Bronze Age.

With the start of the Bronze Age, the Únětice culture appeared. It's named after a village near Prague where it was first discovered. Many of their burial mounds were found, especially in central Bohemia. After them came the Tumulus culture around 1600 BC. The Urnfield culture (1300-800 BC) is known for burning their dead and burying the ashes in urns. The Hallstatt culture was the last culture of the Late Bronze Age and early Iron Age. A special bronze bull statue was found at their main site, the Býčí skála Cave.

Iron Age: Celts, Germans, and Romans

Celtic tribes settled the area at the start of the Iron Age. The most important tribe in Bohemia was the Boii, who gave the region its name, Boiohaemia. Before the 1st century CE, various Germanic tribes like the Marcomanni and Quadi pushed the Celts out. Around 60-50 BC, the Dacian king Burebista's empire reached into the lands of the Boii. After Burebista died, his empire broke apart, freeing the Boii lands.

Signs of Roman army camps were found in south Moravia, especially near Mušov. The winter camp in Mušov could hold about 20,000 soldiers. The Romans often fought the Marcomanni tribe during the first two centuries CE.

Arrival of the Slavs: A New Beginning

The next few centuries, known as the Great Migration, changed the people living in the Czech lands again. In the 500s, Slavic tribes moved into the Czech lands from the east. They often fought with the neighboring Avars, who were nomads who raided Slavic lands.

Samo's Realm: The First Slavic State

In 623, Slavic tribes rebelled against the Avars. A Frankish merchant named Samo supposedly joined the Slavs and helped them defeat the Avars. The Slavs then chose Samo as their ruler. Later, Samo and the Slavs fought against the Frankish empire. In 631, Samo's new kingdom successfully defended its freedom in the Battle of Wogastisburg. After Samo died, his kingdom broke apart.

Medieval Times: Kingdoms and Dynasties

Great Moravia: A Powerful Slavic Kingdom

The kingdom of Great Moravia likely started in the 830s in today's Moravia and western Slovakia. It saw the rise of the first Slavic written language, Old Church Slavonic language, and the creation of the Glagolitic alphabet. This alphabet was later simplified into the Cyrillic alphabet used today in Russia and other countries.

St. Cyril and St. Methodius created Glagolitic. They arrived in Great Moravia in 863 from the Byzantine Empire. King Rastislav invited them to bring literacy and a legal system. His nephew, Svatopluk I, focused more on Rome. Great Moravia came under the protection of the Holy See in 880. During Svatopluk's rule, Great Moravia was at its strongest. After his death, the kingdom split among his sons and soon fell apart due to internal fights and constant Magyar raids in the early 900s.

Duchy of Bohemia: The Přemyslid Rulers

Bořivoj, from the Přemyslid family, was the first known ruler. In 880, he moved his home to Prague Castle, which later became the city of Prague. He was a ruler under Great Moravia and was baptized by St. Cyril and St. Methodius. His son, Spytihněv I, used the fall of Great Moravia to swear loyalty to the East Frankish king in 895.

Spytihněv's nephew, Wenceslaus (later a Catholic saint), ruled from 921. He had to accept the Saxon king's power to keep his own rule. His younger brother, Boleslaus I, murdered him. Boleslaus I expanded the Duchy of Bohemia to the east, taking Moravia, Silesia, and areas around Kraków. He stopped paying tribute to the Saxon king, which led to a war he lost. He then had to accept Saxon rule over Bohemia. The Bishopric of Prague was founded in 973 during the rule of his son, Boleslaus II.

In 1002, during Duke Vladivoj's rule, the Duchy of Bohemia officially became part of the Holy Roman Empire. After some family conflicts, Oldřich took power. His son, Břetislav I, led many conquests and later rebelled against the Holy Roman Emperor Henry III to gain full freedom for Bohemia. Despite early success, he lost to the imperial army and had to give up all his conquests except Moravia, accepting Henry III as his ruler.

After Břetislav died, the Přemyslid family continued to fight among themselves. Some notable rulers, like Vratislaus II and Vladislaus, were given lifetime titles of kings by the Holy Roman Emperors for their service.

Kingdom of Bohemia: A New Era

Late Přemyslids: Expanding the Kingdom

In 1212, Ottokar I was granted the hereditary title of King of Bohemia by Emperor Frederick II. This started the Kingdom of Bohemia, which lasted until the end of World War I. His reign also saw the start of German settlement eastward, which slowly changed the languages spoken in the Czech Lands.

His son, Wenceslaus I, had to deal with the Mongol invasion of Europe in the early 1240s. He successfully defended Bohemia, but Moravia was badly damaged. When the Duke of Austria died without male heirs, Wenceslaus I tried to gain Austrian lands for his son, but his son died early. Wenceslaus I then invaded Austria and succeeded.

His successor, Ottokar II, continued to expand the kingdom. He gained more land south of Austria and led two crusades. He hoped to become Emperor but lost the election in 1273 to Rudolf of Habsburg. Rudolf demanded that Ottokar II return all the lands he had gained south of Bohemia. Ottokar refused and fought two wars against the emperor, dying in the Battle on the Marchfeld in 1278.

The crown went to his 6-year-old son, Wenceslaus II. After some regents, Wenceslaus II began ruling independently in 1290. A year later, he also became King of Poland. In the late 1200s, huge silver deposits were found in Kutná Hora. This allowed him to mint many silver coins called Prague groschen. In 1301, another king died, and Wenceslaus II had his son, Wenceslaus III, crowned King of Hungary. Four years later, Wenceslaus II died at only 33, likely from tuberculosis.

Wenceslaus III gave up his claim to the Hungarian throne. Before he could fight for his rule in Poland, he was murdered in Olomouc by unknown attackers.

House of Luxembourg: Charles IV's Golden Age

Wenceslaus III was the last male of the main Přemyslid family. The Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII of the House of Luxembourg married his son, John of Luxembourg, to Wenceslaus III's sister, Elisabeth, securing the Bohemian throne for him. John was raised in Paris, didn't speak Czech, and was not popular with Czech nobles. He traveled a lot and fought in many wars. In 1336, he lost his eyesight, earning him the nickname John the Blind. He died in 1346 in the Battle of Crécy.

His eldest son, Charles IV, became King of Bohemia.

Earlier in 1346, the Pope declared Emperor Louis IV a heretic and called for a new election. Charles IV was the Pope's choice and was crowned King of Romans. Charles had been managing the Czech Lands since 1333 because his father was often away or ill. Soon after becoming King of Bohemia and King of Romans, he settled in Prague. He started building the New Town, expanding the capital.

In 1348, he founded the University of Prague, the first university north of the Alps and east of Paris. He also legally established the Lands of the Bohemian Crown, meaning the core territories belonged to the Bohemian monarchy itself, not just a king or family.

In 1355, Charles IV traveled to Rome and was crowned Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He ruled as Emperor for over 20 years and made sure his eldest son, Wenceslaus IV, would become King of Romans.

Wenceslaus IV was not as good a ruler as his father. In 1393, the murder of a church official led to a noble rebellion. He was imprisoned and only released after his younger brother, Sigismund, who was King of Hungary, intervened. In 1400, Wenceslaus IV was removed as Holy Roman Emperor. Two years later, Sigismund briefly imprisoned Wenceslaus IV again.

In 1414, Sigismund called the Council of Constance, which resolved a split in the Papacy. It also condemned the teachings of Jan Hus, a popular church reformer and rector of the University of Prague. When Jan Hus refused to change his teachings, he was publicly executed. This sparked the Hussite Wars. These religious wars ended in 1434, but religious tensions continued. Sigismund became the King of Bohemia after Wenceslaus IV's death in 1419, but was only fully recognized in 1436. He died a year later.

House of Habsburg: A Short Rule

After Sigismund's death, the title of King of Bohemia went to his son-in-law, Albert from the House of Habsburg, who died soon after. The claim then passed to his unborn son, Ladislaus, who was raised at the court of Emperor Frederick III. Although he was crowned King of Bohemia in 1453, his regent, George of Poděbrady, effectively ruled Bohemia. Ladislaus died in Prague at age seventeen. Many thought he was poisoned, but modern tests show he died of leukemia. His death ended this line of the Habsburg family.

House of Poděbrady: King of Two Peoples

In 1458, the nobles of Bohemia elected George of Poděbrady as the new King of Bohemia. He had a tough job trying to keep peace between Catholics and Hussites, earning him the nickname "King of two peoples." Despite his efforts, Catholic nobles formed a group against him in 1465. A year later, the Pope excommunicated him, giving the Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus a reason to invade the Czech Lands and start a war.

House of Jagiellon: Uniting Crowns

After King George's death, Vladislaus II from the House of Jagiellon continued the war. George of Poděbrady himself had offered him the Bohemian throne. After ten years of fighting, the war ended in 1479. Moravia, Silesia, and Lusatia were given to Matthias Corvinus for his lifetime, and both kings could use the title King of Bohemia.

In 1485, Vladislaus II confirmed that all Bohemian nobles and commoners could freely follow either Hussitism or Catholicism. After Matthias Corvinus died in 1490, Vladislaus II was elected King of Hungary and regained all the territories he had given up. He then ruled from Buda. Vladislaus II had two children late in life: a son, Louis, and a daughter, Anne. His children married two children of Emperor Maximilian I, linking the Jagiellon and Habsburg families.

In 1516, Vladislaus II died, and his ten-year-old son, Louis II, became king of both Hungary and Bohemia. In 1521, he refused to pay tribute to the Ottoman sultan, Süleyman I, and executed his ambassadors. War followed, and Belgrade fell to the Ottomans. In 1526, Louis II led his forces against Suleiman I in the Battle of Mohács. The Hungarian army suffered a huge defeat, and Louis II drowned while trying to retreat. He had no children, so the Lands of the Bohemian Crown were inherited by Ferdinand I from the House of Habsburg, as had been agreed.

Part of Habsburg Monarchy: Religious Changes and Revival

Protestantism and Conflict

After the Battle of Mohács, the Ottomans failed to take Vienna in 1529. Ferdinand I signed a treaty, delaying Ottoman expansion. Ferdinand and his brother, Emperor Charles V, also faced the Schmalkaldic League, which protected Lutheran states. Many Protestant Czech nobles supported the League. So, when Ferdinand I ordered the Czech nobles to raise an army against the Protestant Electorate of Saxony in 1546, they did so unwillingly.

The next year, the Czech nobles refused to gather an army again and rebelled. They were punished after the Schmalkaldic League lost a major battle. As a result, Ferdinand I strengthened his power in Bohemia, limited city rights, and began bringing Catholicism back by inviting the Jesuit Order to Prague in 1556.

Maximilian II became emperor in 1562 and ruled from Vienna. He approved the Czech Confession, a document confirming religious freedoms for Protestants. He also protected Jews in Bohemia. His son, Rudolf II, became emperor in 1576 and moved the royal court to Prague in 1583. Prague became a major cultural center under Rudolf, who loved art. He was a quiet ruler who preferred his hobbies to state affairs.

In 1605, Rudolf II's family forced him to give Hungary to his younger brother, Archduke Matthias. Differences between the brothers led to Rudolf's imprisonment at Prague Castle, and Matthias took over. After Rudolf II died in 1612, the royal court moved back to Vienna. Matthias had no children and died six years later.

His cousin, Ferdinand II, became emperor. The Bohemian nobles confirmed Ferdinand's position only after he promised to respect the Letter of Majesty, a document granting religious freedoms signed by Rudolf II. However, Ferdinand II was not as tolerant. A year after his coronation, he banned building Protestant churches on royal land. This led to protests among Protestant nobles, who saw it as breaking the Letter of Majesty.

This led to the Second Defenestration of Prague in 1618, which started the Thirty Years War. The rebelling Bohemian nobles chose Frederick V as their new king and prepared for war. Ferdinand II asked his Spanish relative for help. Spanish forces prevented other Protestant armies from joining the Bohemian revolt. After dealing with rebels in Austria, Ferdinand II decisively defeated Frederick V at the Battle of White Mountain near Prague.

Widespread confiscation of property followed, which was then sold to loyal nobles, often from other countries. Ferdinand II also had 27 leaders of the revolt publicly executed and strengthened royal power. The Czech Lands, especially Silesia, were hit hardest by the devastating Thirty Years War. The war continued even after Ferdinand II's death during the reign of Ferdinand III.

Absolutism and National Revival: Habsburg Rule and Czech Awakening

Late Habsburgs: Centralization and Reforms

In 1648, the Thirty Years War finally ended. Ferdinand III continued his father's policies of making the country more Catholic and centralizing power. After his death in 1657, his son, Leopold I, became emperor. During a war with the Ottomans in 1663, the Turkish army invaded Moravia before being stopped. Leopold continued fighting wars with the Ottomans and France. He increased forced labor (corvée) to three days a week, which caused the Peasant Revolt of 1680. More protests against corvée happened, but they failed. In 1705, Leopold I's rule ended, and his son, Joseph I, succeeded him. Joseph I planned many reforms but died young from smallpox.

Charles VI had no sons. With the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, he made sure his titles could be inherited by a woman. He got other European powers to agree. Still, after her father's death, Maria Theresa had to defend her inheritance from a coalition of countries in the War of Austrian Succession in 1740. She managed to keep her title but lost Silesia to Prussia. This ended the unity of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown. In 1757, during the Seven Years' War, the Prussians invaded Bohemia again and besieged Prague. They later lost a battle and were pushed back. Maria Theresa could not regain Silesia, and the war ended in a draw.

Maria Theresa tried to follow Enlightenment ideas. She started compulsory secular primary schools but also censored books against the Catholic religion. Because she married Francis Stephen of Lorraine, her children were part of the new House of Habsburg-Lorraine.

House of Habsburg–Lorraine: Enlightenment and Nationalism

After Maria Theresa's husband died in 1765, her son, Joseph II, ruled with her and then alone from 1780. He made many reforms, including ending serfdom, expanding religious freedom, and closing monasteries not involved in education, healthcare, or science. To centralize power, he also pushed for the German language to be used everywhere. Both his wives died young, and he had no sons, so his younger brother, Leopold II, succeeded him.

Although Leopold II ruled for only two years, he spent several weeks in Prague in 1791 and was crowned King of Bohemia. The first Czech Industrial Exhibition was held for his visit, and the Czech nobles commissioned an opera from Mozart. Leopold II was succeeded by Francis I, his eldest son.

In 1805, Napoleon's army defeated the Austrian and Russian armies in the Battle of Austerlitz in south Moravia. In the peace treaty, Francis I lost many territories, and soon after, the Holy Roman Empire dissolved. After the Napoleonic Wars ended, the Congress of Vienna in 1815 restored the Austrian Empire as a major European power. Francis I supported traditional ways and suppressed new liberal and nationalist movements. He was the first Austrian monarch to widely use secret police and increased censorship.

His son, Ferdinand I, became Austrian Emperor. Because of his frequent seizures, he was not able to rule well, and a Regent's Council held the real power. In 1836, he was crowned King of Bohemia as Ferdinand V.

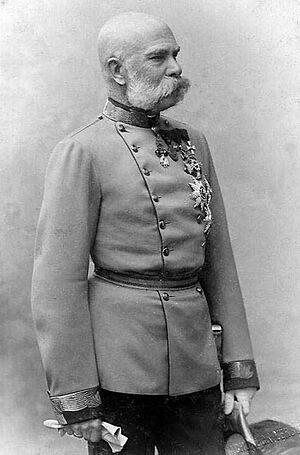

Throughout the 1800s, nationalist movements in the Czech lands, known as the Czech National Revival, slowly grew. Leaders included linguists Josef Dobrovský and Josef Jungmann, historian and politician František Palacký, writer Božena Němcová, and journalist Karel Havlíček Borovský. These efforts first peaked during the revolutions of 1848. Ferdinand I was forced to step down, and his young nephew, Francis Joseph I, became emperor.

When Francis Joseph I lost wars with Italy in 1859 and Prussia in 1866, Hungarian leaders forced him to end his absolute rule over Hungary. This led to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. Czech leaders, who hoped for similar freedom, were left out, and the Czech lands remained under Austrian control.

Austria-Hungary: Towards Independence

The new union of Austria-Hungary lasted for 50 years. Policies suppressing the Czech National Revival continued under the Austrian government. The end of the 1800s also saw a population boom and rapid growth of cities. Populations in industrial centers doubled or tripled in a few decades.

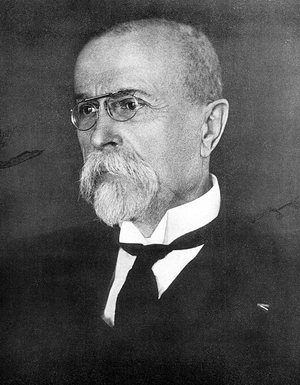

In the early 1900s, Austria's takeover of Bosnia in 1908 caused the Bosnian Crisis. This eventually led to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, sparking World War I in 1914. Many Czech nationalists saw the war as a chance to gain full independence from Austria-Hungary. Czech soldiers often deserted, and Czechoslovak Legions were formed to fight for the Allied Powers. In 1915, Czech and Slovak leaders declared their goal of creating a common state based on self-determination. When World War I ended in 1918, the Kingdom of Bohemia officially ended, and the new democratic republic of Czechoslovakia took its place.

Modern Times: Republic and Division

Czechoslovakia: A New Nation

The Republic of Czechoslovakia was declared in October 1918. It was a democratic presidential republic. In 1920, its territory included not only Czechs and Slovaks but also many Germans (23%), Hungarians (5.5%), and Ruthenians (3.4%). The Great Depression in the late 1920s and the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany in the 1930s caused growing tensions among different nationalist groups in Czechoslovakia.

In foreign relations, the new republic relied heavily on its Western allies, Great Britain and France. This proved to be a mistake. In 1938, both allied countries agreed to Hitler's demands and signed the Munich Treaty. This took away Czechoslovakia's borderlands, leaving it defenseless.

German Protectorate: World War II Era

After giving up Sudetenland, the Second Czechoslovak Republic lasted only half a year before it was completely broken apart before World War II. The Slovak Republic declared independence and became a German client state. Two days later, the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was created. During World War II, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia became a major center for military production for Germany.

The oppression of ethnic Czechs increased after the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich by members of the Czech resistance in 1942. After Germany's defeat in 1945, most ethnic Germans were forcefully deported from Czechoslovakia.

Rule of the Communist Party: Cold War Era

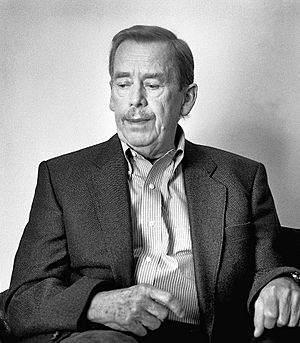

In February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia took power in a coup. Klement Gottwald became the first communist president. He nationalized industries and collectivized farms, following the Soviet model. Czechoslovakia became part of the Eastern Bloc. Attempts to reform the political system during the Prague Spring of 1968 were ended by an invasion of armies from the Warsaw Pact. Czechoslovakia remained under Communist Party rule until the Velvet Revolution of 1989.

Post-Cold War: The Czech Republic Today

One of the leaders of the dissent movement, Václav Havel, became the first president of democratic Czechoslovakia. Slovakia's demands for sovereignty were met in late 1992. Czech and Slovak representatives agreed to split Czechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. The current Czech Republic officially began on January 1, 1993. The Czech Republic joined NATO on March 12, 1999, and the European Union on May 1, 2004.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la República Checa para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la República Checa para niños

- Lech, Czech and Rus

- Czech Silesia

- Politics of the Czech Republic

- Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

Lists:

- List of presidents of Czechoslovakia

- List of prime ministers of Czechoslovakia

- List of presidents of the Czech Republic

- List of prime ministers of the Czech Republic

- List of rebellions in the Czech Republic

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |