Tomáš Masaryk facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

|

|

|---|---|

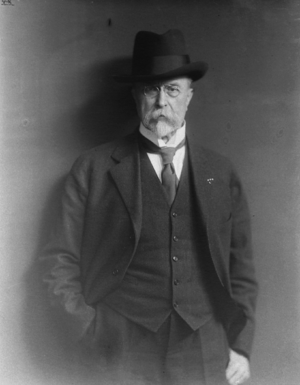

Masaryk in 1925

|

|

| President of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 14 November 1918 – 14 December 1935 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Edvard Beneš |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 7 March 1850 Göding, Margraviate of Moravia, Austrian Empire (now Czech Republic) |

| Died | 14 September 1937 (aged 87) Lány, Czechoslovakia |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | Charlotte Garrigue |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater | University of Vienna (PhD, 1876; Dr. hab., 1879) |

| Profession | Philosopher |

| Signature | |

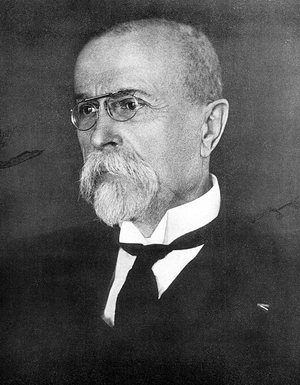

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (born March 7, 1850 – died September 14, 1937) was a very important Czechoslovak politician, leader, and thinker. He was also a sociologist and philosopher.

Before 1914, he wanted to change the Austro-Hungarian Empire into a group of equal states. But after World War I ended in 1918, he worked with other countries to make Czechoslovakia an independent nation. He helped create Czechoslovakia with Milan Rastislav Štefánik and Edvard Beneš. Masaryk then became the first president of this new country.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Tomáš Masaryk was born into a poor family. His birthplace was Hodonín, a city in what is now the Czech Republic. At that time, it was part of the Austrian Empire. His father, Jozef, was a carter and later worked on a large estate.

His mother, Teresie, was a cook. She had a German education. They met at the estate and got married in 1849. Tomáš grew up in the village of Čejkovice before moving to Brno to study.

Education and Early Career

Masaryk went to grammar school in Brno and Vienna from 1865 to 1872. He then studied at the University of Vienna. He earned his Ph.D. from the university in 1876. From 1876 to 1879, he also studied in Leipzig.

In 1878, Masaryk married Charlotte Garrigue, whom he had met in Leipzig. They lived in Vienna until 1881, then moved to Prague.

In 1882, Masaryk became a professor of philosophy at the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague. The next year, he started a magazine called Athenaeum. This magazine focused on Czech culture and science.

Masaryk was a strong believer in science. He thought that many social and political problems came from a lack of knowledge. He believed that by studying these problems scientifically, people could find the right solutions. He saw himself as a teacher who could help people learn and understand.

A Leader for His People

Masaryk served in the Austrian parliament from 1891 to 1893. He was part of the Young Czech Party. Later, from 1907 to 1914, he was in the Czech Realist Party, which he had started in 1900. At this time, he was not yet pushing for Czech and Slovak independence.

When World War I began in 1914, Masaryk decided that the best path was to seek independence. He left his home in December 1914 with his daughter, Olga. They traveled to many places, including Western Europe, Russia, the United States, and Japan.

While in exile, Masaryk worked to organize Czechs and Slovaks living outside Austria-Hungary. He made important connections that would help Czechoslovakia become independent. He gave speeches and wrote many articles to support the idea of a free Czechoslovakia.

Masaryk was key in forming the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia. This group of soldiers fought for the Allied Powers during World War I. In 1915, he became a professor at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies in London. He lectured about the challenges faced by smaller nations.

The Czechoslovak Legion and US Visit

In August 1914, Russia allowed a group of Czechs and Slovaks to form a battalion. This unit went to the front lines in October 1914. Masaryk wanted to make this group much larger. He hoped to recruit Czech and Slovak prisoners of war (POWs) held in Russian camps.

At first, Russia allowed this, but then changed its mind. It was not until 1917 that the Czechs and Slovaks were officially allowed to recruit POWs. Despite this, the Czechoslovak armed unit in Russia slowly grew.

Masaryk focused on influencing important leaders rather than just public opinion. In October 1915, he gave a speech in London. He argued that Britain should support the independence of "small" nations like the Czechs. He also gave a speech in Paris, talking about "The Slavs Among the Nations."

During the war, Masaryk's network of Czech revolutionaries gathered important information for the Allies. This network helped uncover a plot in San Francisco. Masaryk also taught at London University and wrote about Czechoslovak independence.

In 1916, Masaryk went to France to convince the French government that Austria-Hungary needed to be broken up. He also met with Russian leaders. After the 1917 February Revolution in Russia, he went there to help organize the Czechoslovak Legion. This group was dedicated to fighting against the Austrians.

After the Czechoslovak troops fought bravely in the Battle of Zborov in July 1917, Russia allowed Masaryk to recruit more volunteers from POW camps. The legion grew to about 40,000 soldiers by 1918.

In 1918, Masaryk traveled to the United States. He met with President Woodrow Wilson and convinced him that his cause was right. On May 5, 1918, over 150,000 people in Chicago welcomed him. Chicago was a major center for Czechoslovak immigrants.

Masaryk had strong ties to the United States. His wife was American, and he had friends who introduced him to important political figures. On October 18, 1918, he gave President Wilson the "Washington Declaration." This document, created with the help of his American friends, was a key step toward founding an independent Czechoslovak state.

First President of Czechoslovakia

When the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell in 1918, the Allied Powers recognized Masaryk as the head of the temporary Czechoslovak government. On November 14, 1918, he was elected president of Czechoslovakia by the National Assembly in Prague. He was still in New York at the time.

Masaryk was re-elected three times: in 1920, 1927, and 1934. The constitution usually limited a president to two terms. However, a special rule allowed Masaryk, as the first president, to run as many times as needed.

Even though the constitution gave the president limited power, Masaryk's influence was very strong. This was because many political parties existed, making it hard for one party to win a majority. This often led to changes in government. Masaryk's steady leadership and high reputation gave Czechoslovakia great stability.

He created an important political network called the "Hrad" (the Castle). Under his leadership, Czechoslovakia became the strongest democracy in Central Europe.

Masaryk visited France, Belgium, England, Egypt, and Palestine in 1923 and 1927. He also supported the first Prague International Management Congress in 1924. After Adolf Hitler came to power, Masaryk was one of the first European leaders to express concern. He resigned from office on December 14, 1935, due to his old age and poor health. Edvard Beneš became the next president.

Death and Lasting Impact

Masaryk died less than two years after leaving office, at the age of 87, in Lány. He did not live to see the Munich Agreement or the Nazi occupation of his country. He was known as the "Grand Old Man of Europe."

Remembering Masaryk

As the "Father of the Nation," Masaryk is highly respected by Czechs and Slovaks.

- Masaryk University in Brno, founded in 1919, was named after him.

- People hold annual events at his grave in Lány on his birthday (March 7) and the day he died (September 14).

- The Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, created in 1990, is a special honor. It is given to people who have made great contributions to humanity, democracy, and human rights.

- Many statues, busts, and plaques honor him in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. There are also statues in Washington, D.C., and Chicago in the United States.

- A main street in Mexico City, Avenida Presidente Masaryk, is named after him.

- The community of Masaryktown, Florida, founded by Slovaks and Czechs, is also named after him.

- In Israel, Masaryk is seen as an important friend. A village called Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk and Masaryk Square in Tel Aviv are named after him. Many other cities in Israel have streets named after him.

- Streets in cities like Zagreb, Belgrade, and Ljubljana are also named Masarykova ulica.

- Asteroid 1841 Masaryk is named after him.

Philosophy and Beliefs

Masaryk's motto was: "Do not fear, and do not steal." He was a philosopher who believed in rationalism and humanism. He focused on practical ethics. He was influenced by thinkers from England, France, and Germany. He did not agree with some German ideas or with Marxism.

Books He Wrote

Masaryk wrote several books in Czech, including:

- The Czech Question (1895)

- The Problems of Small Nations in the European Crisis (1915)

- The New Europe (1917)

- The World Revolution (1925), which was translated into English as The Making of a State (1927).

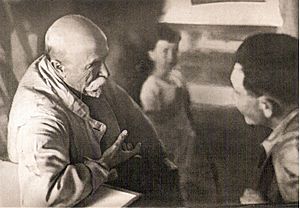

The writer Karel Čapek wrote a series of articles called Hovory s T.G.M. ("Conversations with T.G.M."). These were later put together as Masaryk's autobiography.

His Family Life

Masaryk married Charlotte Garrigue in 1878. He added her family name to his own. Charlotte was from Brooklyn, USA, and came from a Protestant family. She learned to speak Czech very well and wrote articles for a Czech magazine. She passed away in 1923.

Their son, Jan, became the Czechoslovak ambassador in London. He also served as the foreign minister in the government. Tomáš and Charlotte had four other children: Herbert, Alice, Eleanor, and Olga.

Masaryk was born a Catholic but later became a non-practicing Protestant. His wife, Charlotte, who was a Unitarian, influenced him.

Family Tree

| Tomáš Masaryk | Charlotte Garrigue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alice | Herbert | Jan | Eleanor | Olga | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See also

In Spanish: Tomáš Masaryk para niños

In Spanish: Tomáš Masaryk para niños

- School of Brentano, a group of philosophers and psychologists who studied with Franz Brentano

- 1841 Masaryk, an asteroid