Edvard Beneš facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edvard Beneš

|

|

|---|---|

Beneš c. 1942

|

|

| President of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 2 April 1945 – 7 June 1948 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Emil Hácha |

| Succeeded by | Klement Gottwald |

| In exile 17 October 1939 – 2 April 1945 |

|

| Prime Minister | Jan Šrámek |

| In office 18 December 1935 – 5 October 1938 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Tomáš Masaryk |

| Succeeded by | Emil Hácha |

| 4th Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 26 September 1921 – 7 October 1922 |

|

| President | Tomáš Masaryk |

| Preceded by | Jan Černý |

| Succeeded by | Antonín Švehla |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 14 November 1918 – 18 December 1935 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Milan Hodža |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 May 1884 Kožlany, Bohemia, Cisleithania, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 3 September 1948 (aged 64) Sezimovo Ústí, Bohemia, Czechoslovakia |

| Nationality | Czech |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse |

Hana Benešová

(m. 1909) |

| Alma mater | |

| Signature |  |

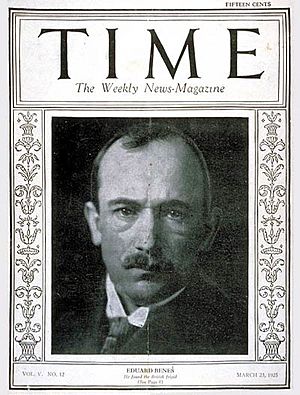

Edvard Beneš (Czech pronunciation: [ˈɛdvard ˈbɛnɛʃ] (![]() listen); 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was an important Czech politician. He served as the president of Czechoslovakia twice. His first term was from 1935 to 1938. His second term was from 1945 to 1948. During World War II, he led the Czechoslovak government-in-exile from 1939 to 1945.

listen); 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was an important Czech politician. He served as the president of Czechoslovakia twice. His first term was from 1935 to 1938. His second term was from 1945 to 1948. During World War II, he led the Czechoslovak government-in-exile from 1939 to 1945.

As president, Beneš faced two big challenges that led to his resignation. The first was the Munich Agreement in 1938. This agreement allowed Nazi Germany to take over parts of Czechoslovakia. This forced his government to go into exile in the United Kingdom. The second challenge was the Communist takeover in 1948. This event created the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. Before becoming president, Beneš was also the first foreign affairs minister (1918–1935) and a prime minister (1921–1922) of Czechoslovakia. He was known as a very skilled diplomat.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Where and When He Was Born

Edvard Beneš was born in 1884 in a small town called Kožlany. This was in the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time. He came from a peasant family. He was the youngest of ten children. One of his brothers, Vojta Beneš, also became a politician.

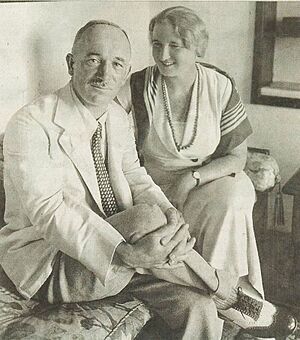

His School Years and Marriage

Beneš spent much of his youth in Prague. He went to a grammar school there from 1896 to 1904. He met his future wife, Anna Vlčková, through his landlord's family. They studied French, history, and literature together in Paris. Edvard and Anna got engaged in 1906 and married in 1909. Anna later changed her name to Hana, which Edvard preferred. Edvard also changed his own name from "Eduard" to "Edvard."

He played soccer as an amateur for Slavia Prague. After studying philosophy in Prague, he continued his studies in Paris. He earned his law degree in 1908. Later, he became a sociology lecturer at Charles University. He was also involved in scouting.

In 1907, Beneš wrote many articles about his experiences in Western Europe. He found Germany to be "an empire of force and power." He also described life in London as "terrible." However, he loved Paris, calling it the "city of light." He felt it was a "magnificent synthesis of modern civilization." For the rest of his life, Beneš loved France and always said Paris was his favorite city.

Starting His Political Career

Working for an Independent Czechoslovakia

During World War I, Beneš worked to create an independent Czechoslovakia. He secretly organized a group called Maffia that was against Austria-Hungary. In 1915, he moved to Paris. There, he worked hard to get France and the United Kingdom to recognize Czechoslovakia's independence. From 1916 to 1918, he was a Secretary of the Czechoslovak National Council in Paris. He also served as a minister in the temporary Czechoslovak government.

In 1917, Beneš, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, and Milan Rastislav Štefánik helped create the "Czechoslovak Legion." This group of tens of thousands of Czechs and Slovaks fought for the Western Allies in France and Italy. They also fought in Russia.

Czechoslovakia's First Foreign Minister

From 1918 to 1935, Beneš was Czechoslovakia's first and longest-serving Foreign Minister. He was very skilled in international matters. He kept this job through 10 different governments. He even led one of these governments himself as prime minister from 1921 to 1922. He represented Czechoslovakia at the peace conference in Paris in 1919. This conference led to the Versailles Treaty.

Beneš believed that Czechs and Slovaks were not separate ethnicities. He served in the National Assembly for many years. He was also a professor for a short time in 1921.

Beneš was an important figure at international meetings. He was a member of the League of Nations Council from 1923 to 1927. He also served as president of its committee from 1927 to 1928. He was known for his influence at conferences like those in Genoa (1922) and Locarno (1925).

First Time as President

When President Tomáš Masaryk retired in 1935, Beneš became the new president. The president's office, known as the Hrad (meaning "the castle"), had a lot of power. By 1938, Beneš was the main decision-maker in Czechoslovakia.

The Sudetenland Crisis

Edvard Beneš did not want Nazi Germany to take the Sudetenland region in 1938. This area had many German-speaking people. The crisis began when a local German party demanded that the Sudetenland become independent. Beneš offered a plan to give the region more freedom, but it was rejected. He wanted to fight Germany if other powerful countries would help Czechoslovakia.

The British government tried to mediate the crisis. They sent Lord Runciman to help. Beneš was a skilled negotiator. He made it seem like the Czech offers were reasonable, and that the Sudeten Germans were being stubborn.

On 30 September 1938, Germany, Italy, France, and the United Kingdom signed the Munich Agreement. This agreement allowed Germany to take over the Sudetenland. Czechoslovakia was not even asked about it. Beneš agreed to this, even though many in his country were against it. France and the United Kingdom had warned that they would not help Czechoslovakia if a war started. Beneš was forced to resign on 5 October 1938. Emil Hácha replaced him.

Many Czechs felt this was a "Western betrayal." However, some historians believe that if war had started in 1938, Czechoslovakia would have been destroyed. Czechoslovakia had strong border defenses, but Germany could have attacked from other directions. Fighting a long war in a small country would have been devastating.

In March 1939, German troops marched into the rest of Czechoslovakia. They made it a "protectorate of Nazi Germany." Slovakia became a separate puppet state. This completed the German occupation of Czechoslovakia until 1945.

Living in Exile During the War

On 22 October 1938, Beneš went into exile in Putney, London. Czechoslovakia's intelligence service, led by František Moravec, stayed loyal to Beneš. They provided valuable information from a German spy. Beneš shared some of this information with the British. This helped him gain influence.

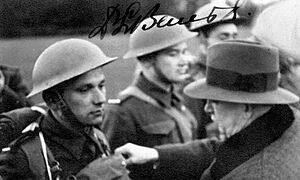

In the summer of 1939, Beneš hoped that a crisis with Germany would lead to war. He saw war as the only way to restore Czechoslovakia. He also started meeting regularly with Winston Churchill, who was then a Member of Parliament.

On 23 August 1939, Beneš met with the Soviet ambassador to ask for Soviet support. He even suggested giving Ruthenia to the Soviet Union to create a shared border. On the same day, he learned about the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact between Germany and the Soviet Union. He believed the Soviets wanted war to start a "world revolution." On 1 September, Germany invaded Poland, and Britain and France declared war.

Setting Up a Government in Exile

In October 1939, Beneš formed the Czechoslovak National Liberation Committee. This group declared itself the Provisional Government of Czechoslovakia. Britain and France did not fully recognize it at first. Beneš wanted Britain to cancel the Munich Agreement. This was important because Britain still saw the Sudetenland as part of Germany.

After the Dunkirk evacuation, Britain faced a possible German invasion. At the same time, 500 Czechoslovak airmen and half a military division arrived in Britain. Beneš used this as a strong argument for recognition. On 21 July 1940, the United Kingdom recognized Beneš's government-in-exile. Beneš argued that his 1938 resignation was forced and therefore not valid.

The intelligence Beneš provided was very important to the British. He used this to get more support for his government. He was invited to lunch by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and even by King George VI. In November 1940, Beneš and his family moved to The Abbey in Buckinghamshire. His staff also moved to nearby villages.

The Soviet Union Joins the War

Beneš had difficult relations with the Polish government-in-exile. They disagreed about the Teschen region. However, Beneš thought a Polish-Czechoslovak alliance was needed after the war. He even considered a Polish–Czechoslovak confederation.

But when Operation Barbarossa brought the Soviet Union into the war in June 1941, Beneš became less interested in the Polish alliance. He felt more comfortable dealing with the Soviets. The Soviet Union promised to support Czechoslovakia getting Teschen back.

On 22 June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Beneš believed the Soviet Union would defeat Germany. He thought the Soviets would play a big role in Eastern Europe after the war. He urged Czech leaders in the Protectorate to resign rather than help the Germans.

On 18 July 1941, the Soviet Union and the UK recognized Beneš's government-in-exile. They promised not to interfere in Czechoslovakia's internal affairs. They also allowed Czechoslovakia to raise an army to fight with the Red Army. Most importantly, they recognized Czechoslovakia's borders as they were before the Munich Agreement. This was a big win for Beneš.

Working with the Czech Resistance

The Allies wanted the Czechs to do more resistance work. They were disappointed there wasn't much sabotage in factories. In late 1941, Reinhard Heydrich took over the Protectorate and cracked down on resistance. Many leaders were arrested and executed. Communication with London was cut off.

Faced with this, Beneš decided on a dramatic act of resistance. In 1941, Beneš and František Moravec planned Operation Anthropoid. This was a mission to assassinate Reinhard Heydrich. Heydrich was a high-ranking German official who was very harsh on Czech culture and resistance. Beneš felt this act would show the world that Czechs were still fighting.

Some resistance leaders asked Beneš to cancel the attack. They worried about the terrible consequences for the Czech people. But Beneš insisted the attack go forward. The assassination happened in 1942. It led to brutal German revenge. Thousands of Czechs were executed, and two villages, Lidice and Ležáky, were completely destroyed.

Britain Rejects the Munich Agreement

In 1942, Beneš finally convinced the British Foreign Office to say that Britain had cancelled the Munich Agreement. They now supported the return of the Sudetenland to Czechoslovakia. Beneš saw this as a great diplomatic victory. He was very angry about how the ethnic Germans in the Sudetenland had acted in 1938. He decided that when Czechoslovakia was rebuilt, he would expel all of them to Germany.

Although not a Communist, Beneš was friends with Joseph Stalin. He believed that Czechoslovakia would benefit more from an alliance with the Soviet Union than with Poland. He stopped plans for a Polish–Czechoslovak confederation. In 1943, he signed an alliance with the Soviets.

Beneš believed that the Soviet Union and Western nations would become more similar after the war. He hoped that the wartime alliance of the "Big Three" (Soviet Union, United Kingdom, and United States) would continue. He saw Czechoslovakia and himself as mediators between these big powers.

Second Time as President

In April 1945, Beneš flew from London to Košice in eastern Slovakia. This city had been taken by the Red Army and became the temporary capital of Czechoslovakia. Beneš formed a new government called the National Front. The leader of the Communist Party, Klement Gottwald, became prime minister. Communists also held important positions like defense and interior ministers.

Beneš also introduced the Košice programme. This plan declared that Czechoslovakia would be a state for Czechs and Slovaks. It said that the German population and Hungarian population would be expelled. It also stated that Czechoslovakia would have a pro-Soviet foreign policy.

His Role in the Prague Uprising

During the Prague uprising in May 1945, the city was surrounded by German forces. The Czech resistance asked a German-sponsored Russian army division to switch sides. They promised them safety in Czechoslovakia. This Russian division helped defend Prague. However, Beneš later sent these soldiers back to the Soviet Union, where they faced severe punishment.

Returning to Prague

After the war, Beneš returned to Prague and became president again. He was confirmed in office by the Interim National Assembly in October 1945. In December 1945, all Soviet forces left Czechoslovakia. In June 1946, Beneš was formally elected for his second term.

Beneš led a coalition government with the Communists. In the 1946 elections, the Communists won the most votes (38%). For a while, Czechoslovakia had a period of peace. Democracy was restored, and things like the media and opposition parties were free.

In July 1947, Beneš and Gottwald wanted to accept Marshall Plan aid from the United States. But the Soviet Union ordered Gottwald to refuse it. When Beneš visited Moscow, the Soviet Foreign Minister told him that accepting the aid would break their 1943 alliance. Beneš called this a "second Munich." He felt it was wrong for the Soviet Union to control Czechoslovakia's decisions. This made public opinion turn against the Communists.

Expelling Germans and Hungarians

Beneš did not want Germans in the newly freed republic. He believed that taking action quickly would be better than long trials. When he arrived in Prague in May 1945, he called for the "liquidation of Germans and Hungarians." This was for the "interest of a united national state of Czechs and Slovaks."

The Beneš decrees were official orders. They took away property from German and Hungarian citizens. They also helped with the Potsdam Agreement by creating laws for taking away citizenship and property from about three million Germans and Hungarians. However, Beneš's plans to expel Hungarians from Slovakia caused problems with Hungary. The Soviet Union eventually stopped the expulsion of Hungarians. But the Soviets had no problem with expelling the Sudeten Germans. So, the Czechoslovak authorities continued to expel them until very few Germans remained.

In March 1946, a high-ranking German official named Karl Hermann Frank was put on trial in Prague for war crimes. Beneš made sure the trial was very public. It was broadcast live on radio. After Frank was found guilty, he was publicly executed in May 1946.

The Communist Takeover of 1948

In February 1948, non-Communist ministers threatened to resign. They were protesting that the police were being filled with Communists. The Communists formed "action committees" and a "people's militia" of 15,000. On 21 February 1948, 12 non-Communist ministers resigned. They wanted to protest the Communist prime minister, Gottwald, who refused to stop putting Communists in the police force. They hoped Beneš would support them.

Beneš at first refused to accept their resignations. He insisted that a government could not be formed without the non-Communist parties. However, Gottwald threatened a general strike if Beneš did not appoint a Communist-led government. The Communists also took over the offices of the resigned ministers.

Faced with this crisis, Beneš hesitated. There were fears of a civil war and rumors that the Red Army would come to help Gottwald. On 25 February, Beneš gave in. He accepted the resignations and appointed a new government. This government was controlled by Communists, even though some non-Communist parties were still technically represented. Beneš had essentially given legal approval to a Communist takeover.

During this time, Beneš did not gather support from groups that could have helped him. He still saw Germany as the main threat to Czechoslovakia. He believed Czechoslovakia needed the alliance with the Soviet Union. Also, Beneš was very ill in February 1948. He suffered from high blood pressure and other health problems. His poor health likely affected his ability to fight.

Soon after, elections were held. Voters could only choose from a single list from the Communist-controlled National Front. On 9 May, a new constitution was approved. It was very similar to the Soviet Constitution. Beneš refused to sign it. He resigned as president on 7 June 1948. Gottwald then took over his duties and was elected as his successor a week later.

After his resignation, Soviet and Czechoslovak media criticized Beneš. They accused him of being an enemy of the Soviet Union. They claimed he refused Soviet military help in 1938. Beneš was very angry about this claim. During the Communist era, Beneš was often called a traitor for supposedly turning down this offer.

Death and What He Left Behind

Beneš was already in poor health after having two strokes in 1947. Seeing his life's work undone by the Communist takeover left him completely broken. He died of natural causes at his home in Sezimovo Ústí on 3 September 1948. This was seven months after the Communist takeover. He is buried in the garden of his villa. His wife Hana, who lived until 1974, is buried next to him.

There is still much debate about his character and decisions. Some historians, like A. J. P. Taylor, praised Beneš. Taylor wrote in 1945 that Beneš's foreign policy during the war had given Czechoslovakia a secure future. He saw Beneš as a man of integrity. This view was widely shared in 1945.

Honors and Awards

He received many awards and decorations before and after World War II.

National Orders

| Award or decoration | Country | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Czechoslovak War Cross 1918 | Czechoslovakia | 1919 | |

| Czechoslovak Victory Medal | Czechoslovakia | 1920 | |

| Czechoslovak Revolutionary Medal | Czechoslovakia | 1922 | |

| Order of the White Lion | Czechoslovakia | 1936 | |

| Czechoslovak War Cross 1939–1945 | Czechoslovakia | 1945 | |

| Military Order of the White Lion | Czechoslovakia | 1945 | |

Foreign Orders

| Award or decoration | Country | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Order of St. Sava | 1920 | ||

| Order of the Star of Romania | 1921 | ||

| Légion d'honneur | 1922 | ||

| Order of the Crown of Italy | 1921 | ||

| Order of the British Empire | 1923 | ||

| Order of Leopold | 1923 | ||

| Order of the Oak Crown | 1923 | ||

| Order of Charles III | 1924 | ||

| Order of Polonia Restituta | 1925 | ||

| Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria | 1926 | ||

| Order of the Three Stars | 1927 | ||

| Order of the Rising Sun | 1928 | ||

| Order of Muhammad Ali | 1928 | ||

| Order of the White Eagle | 1929 | ||

| Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas | 1929 | ||

| Order of the Cross of the Eagle | 1931 | ||

| Military Order of Christ | 1932 | ||

| Military Order of Saint James of the Sword | 1933 | ||

| Order of the Redeemer | 1933 | ||

| Order of the Dannebrog | 1933 | ||

| Order of Saint-Charles | 1934 | ||

| Order of the Spanish Republic | 1935 | ||

| Order of the White Elephant | 1935 | ||

| Order of the Aztec Eagle | 1935 | ||

| Order of Karađorđe's Star | 1936 | ||

| Order of Brilliant Jade | 1936 | ||

| Order of Boyaca | 1937 | ||

| Order of Carol I | 1937 | ||

| Order of Pahlavi | 1937 | ||

| Order pro Merito Melitensi | 1938 | ||

| Order of St. Olav | 1945 | ||

| Order of Propitious Clouds | 1947 | ||

See also

In Spanish: Edvard Beneš para niños

In Spanish: Edvard Beneš para niños