A. J. P. Taylor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

A. J. P. Taylor

|

|

|---|---|

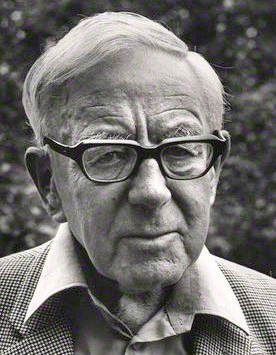

Taylor in 1977

|

|

| Born |

Alan John Percivale Taylor

25 March 1906 Southport, England

|

| Died | 7 September 1990 (aged 84) London, England

|

| Alma mater | Oriel College, Oxford |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Awards | Fellow of the British Academy |

Alan John Percivale Taylor (born March 25, 1906 – died September 7, 1990) was a famous British historian. He was an expert in European diplomacy from the 1800s and 1900s.

Taylor was also a journalist and a TV personality. Millions of people knew him from his history talks on television. He was great at both serious academic work and making history fun for everyone. Because of this, he was called the "Macaulay of our age," comparing him to another great historian. In a 2011 poll, he was named the fourth most important historian of the past 60 years.

Contents

Life of A. J. P. Taylor

Early Years and Education

Alan John Percivale Taylor was born in 1906 in Birkdale, England. He was the only child of Percy Lees Taylor, a cotton merchant, and Constance Sumner Taylor, a schoolteacher. His parents were wealthy and had strong left-wing views, which Alan inherited.

His parents were also pacifists, meaning they were against war. They sent Alan to Quaker schools to protest against the First World War. These schools included The Downs School and Bootham School. In 1924, he went to Oriel College, Oxford, to study history.

In the 1920s, Taylor's mother was involved with the Comintern, an international communist organization. One of his uncles helped start the Communist Party of Great Britain. Alan himself joined the Communist Party for a short time from 1924 to 1926. He left because he felt the party didn't do enough during the 1926 General Strike in the UK. After that, he supported the Labour Party for over sixty years. He visited the Soviet Union in 1925 and again in 1934.

University Career

Taylor finished his studies at Oxford in 1927 with top honors. After a brief job as a legal clerk, he started his advanced studies. He went to Vienna to research the Chartist movement and its impact on the 1848 Revolution. When that topic didn't work out, he switched to studying Italian unification. This led to his first book, The Italian Problem in European Diplomacy, 1847–49, published in 1934.

From 1930 to 1938, Taylor taught history at the University of Manchester. He then became a Fellow at Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1938, where he stayed until 1976. He also taught modern history at the University of Oxford from 1938 to 1963. He was so popular at Oxford that he had to give his lectures early in the morning to avoid overcrowding.

In 1964, the University of Oxford decided not to renew his teaching position. This happened after some debate about his book The Origins of the Second World War. He then moved to London and taught at the Institute of Historical Research and the Polytechnic of North London.

World War II Involvement

During the Second World War, Taylor was part of the British Home Guard. He became friends with leaders from Central Europe who had moved to Britain, like the former Hungarian President Count Mihály Károlyi and Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš. These friendships helped him understand that part of the world better.

In 1943, Taylor wrote a pamphlet called Czechoslovakia's Place in a Free Europe. In it, he suggested that after the war, Czechoslovakia could be a "bridge" between Western countries and the Soviet Union. During the war, he also worked for the Political Warfare Executive, sharing his knowledge about Central Europe. He often spoke on the radio and at public meetings. He also supported Josip Broz Tito's Partisans as the rightful government of Yugoslavia.

Later Life and Family

In 1979, Taylor resigned from the British Academy. He did this to protest their decision to remove Anthony Blunt, who was found to be a Soviet spy. Taylor saw this as unfair.

Taylor was married three times. His first wife was Margaret Adams, whom he married in 1931. They had four children and divorced in 1951. His second wife was Eve Crosland, whom he married in 1951. They had two children and divorced in 1974. His third wife was the Hungarian historian Éva Haraszti, whom he married in 1976.

A. J. P. Taylor's Key Works

Taylor's main area of study was Central European, British, and diplomatic history. He was especially interested in the Habsburg dynasty and Bismarck.

Early Books

His first book, The Italian Problem in European Diplomacy, 1847–49, was published in 1934. In 1941, he wrote The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918. In this book, Taylor argued that the Habsburg rulers mainly saw their lands as a way to conduct foreign policy. He believed they struggled to create a true nation-state.

The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918

In 1954, Taylor published his major work, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918. This book looked at how different European powers competed for control during that period. He followed this with The Trouble Makers in 1957, which was about people who had disagreed with British foreign policy.

Bismarck: The Man and the Statesman

Taylor's best-selling biography of Bismarck came out in 1955. He made a controversial argument that Otto von Bismarck unified Germany more by chance than by a grand plan. This idea went against what many other historians believed.

The Origins of the Second World War

In 1961, Taylor published his most debated book, The Origins of the Second World War. This book made him known as a "revisionist" historian, someone who challenges common historical views.

In the book, Taylor argued against the popular idea that Adolf Hitler had a clear plan to start the Second World War. He believed that the war in 1939 was an unfortunate accident. He said it was caused by mistakes made by many leaders, not just Hitler's evil plan.

Taylor saw Hitler as a normal German leader in foreign affairs, not a unique evil figure. He argued that Hitler wanted Germany to be the strongest power in Europe but didn't necessarily plan for a big war. Taylor also believed that the Treaty of Versailles after World War I was flawed. He felt it was harsh enough to make Germans hate it but not strong enough to stop Germany from becoming a major power again.

English History 1914–1945

After the debate over his previous book, Taylor had a huge success with English History 1914–1945 in 1965. This book was his only work on social history and cultural history. It offered a warm look at Britain between 1914 and 1945. It became a best-seller, selling more copies in its first year than all previous volumes of the Oxford History of England combined.

War by Timetable

In his 1969 book War by Timetable, Taylor explored how the First World War began. He concluded that no major power wanted war in 1914. Instead, they all believed that being able to mobilize their armies faster than others would prevent war. However, this led to complex military timetables. When the crisis of 1914 happened, these timetables pushed countries towards war, even if their leaders didn't intend it.

Beaverbrook: A Biography

Taylor became friends with Lord Beaverbrook in the 1950s and 1960s. He later wrote Beaverbrook's biography in 1972. Lord Beaverbrook was a Conservative politician who believed strongly in the British Empire. Taylor was fascinated by politics and politicians, even though he often criticized them in his writings.

Public Life and Media

Journalism

Taylor started working as a book reviewer for the Manchester Guardian in 1931. From 1957, he wrote a column for the Observer. He also wrote for tabloid newspapers like the Sunday Pictorial and the Daily Herald.

From 1957 to 1982, he wrote for the Sunday Express, which was owned by his friend Lord Beaverbrook. In his articles, Taylor often wrote about his Euroscepticism, meaning he was against Britain joining the European Economic Community. He also often criticized the BBC and the anti-smoking movement.

Broadcasting

During World War II, Taylor started working in radio and later television. He first appeared on BBC radio in 1942. After the war, he became one of the first historians to appear on television. He was a panelist on the BBC's In The News from 1950 to 1954. He was known for his strong opinions and sometimes argumentative style.

From 1955, Taylor was a panelist on ITV's Free Speech. In 1957, he started giving half-hour lectures on ITV without notes, covering topics like the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the First World War. These shows were very popular. He continued to make historical series for both the BBC and ITV throughout his career.

Taylor had a well-known rivalry with historian Hugh Trevor-Roper. They often debated on television. One famous exchange happened in 1961 when Trevor-Roper criticized Taylor's book The Origins of the Second World War. Taylor's frequent TV appearances made him the most famous British historian of the 20th century.

A. J. P. Taylor's Views

Throughout his life, Taylor often spoke out on important issues. In the early 1930s, he was part of a left-wing pacifist group. At first, he was against Britain rearming its military. However, after 1936, he changed his mind. He then urged Britain to rearm against the Nazi threat and supported an alliance with the Soviet Union.

He strongly criticized appeasement, the policy of giving in to aggressive powers like Nazi Germany. In October 1938, he spoke out against the Munich Agreement, which allowed Germany to take parts of Czechoslovakia.

Taylor was generally sympathetic to the Soviet Union's foreign policy, especially after 1941 when they became Britain's ally. He was very grateful for the Red Army's role in defeating Nazi Germany. However, he was critical of Stalinism, the harsh rule of Joseph Stalin.

As a socialist, Taylor believed the capitalist system was wrong. He felt it was unstable and prevented a fair international system. He also blamed the United States for the Cold War. In the 1950s and 1960s, he was a leader in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, which called for getting rid of nuclear weapons. He believed Britain should be neutral in the Cold War, or if it had to choose, it should align with the Soviet Union rather than America.

He also opposed the British Empire and Britain's involvement in the European Economic Community and NATO.

Taylor was known for supporting unpopular people and causes. In 1980, he resigned from the British Academy to protest the removal of art historian and Soviet spy Anthony Blunt. He saw this as an act of McCarthyism, which is when people are unfairly accused of disloyalty.

Views on Germany

Taylor held strong anti-German views. In his 1945 book, The Course of German History, he argued that National Socialism was a natural outcome of German history. He believed there was a strong connection between Hitler and the German people. He accused Germans of constantly expanding eastward against their Slavic neighbors since the time of Charlemagne. This book was a best-seller and helped make Taylor famous in the United States.

Populist Approach to History

Taylor believed that history should be available to everyone. He liked being called the "People's Historian." He often argued that history is made more by the mistakes of leaders than by their genius. He felt that leaders mostly reacted to events, and what happened in the past was often due to a series of errors that no one fully controlled.

While he often showed leaders as making blunders, he did believe some individuals could play a positive role. His heroes included Vladimir Lenin and David Lloyd George. Even though he later had mixed feelings about appeasement, Winston Churchill remained one of his heroes. In English History 1914–1945, he famously called Churchill "the saviour of his country."

Humor and Irony

Taylor used humor and irony in his writing and talks to make history entertaining. He would look at history from unusual angles, pointing out the silly parts of historical figures. He was famous for his "Taylorisms," which were witty and sometimes puzzling remarks. These remarks were meant to show the strange parts of modern international relations. For example, he said about the dictator Benito Mussolini, "kept up with his work – by doing none."

His desire to share history with everyone led to his many appearances on radio and television. He also made sure to show that historians aren't always right. When asked about the future, he once said, "Dear boy, you should never ask an historian to predict the future – frankly we have a hard enough time predicting the past."

Criticisms of A. J. P. Taylor

The Origins of the Second World War Criticisms

When The Origins of the Second World War was published in 1961, it caused a big debate. Many historians criticized Taylor's ideas. They disagreed with his arguments that appeasement was a reasonable strategy. They also didn't like his idea that the Second World War was an "accident" caused by diplomatic mistakes. Many also disliked his portrayal of Hitler as a "normal leader" and his dismissal of Nazi ideas as a driving force.

His main critic was Hugh Trevor-Roper, who argued that Taylor had wrongly interpreted the evidence. Trevor-Roper believed that Hitler clearly intended to go to war, regardless of the specific plans. Many other historians also criticized the book.

Despite the criticism, The Origins of the Second World War is seen as a very important book in the study of how the Second World War began. Historians have praised Taylor for:

- Making people think about whether fascist states followed a strict plan or just took advantage of situations.

- Showing connections in German foreign policy between 1871 and 1939, which helped put Nazi foreign policy in a broader context.

- Highlighting that appeasement was a popular policy in Britain, not just something a small group did.

- Showing that the Anschluss (Germany's annexation of Austria) was very popular in Austria.

- Being one of the first to present Hitler as a regular human being, though with terrible beliefs, which helped explain his actions.

Views on Mussolini

Taylor described Benito Mussolini as a great showman but a weak leader with no strong beliefs. While many agree he was a showman, some historians disagree that he had no beliefs. Taylor argued that Mussolini was sincere in trying to work with Britain and France against Germany. He believed that the League of Nations' economic punishments against Italy for invading Ethiopia pushed Mussolini into an alliance with Nazi Germany. However, some experts on Italian history argue that Mussolini had a clear foreign policy goal of expanding Italy's influence in the Mediterranean, which would have led to conflict anyway.

Retirement and Death

In 1984, Taylor was badly injured when he was hit by a car in London. This accident led to his retirement in 1985. In his final years, he suffered from Parkinson's disease, which made it impossible for him to write. His last public appearance was at his 80th birthday in 1986. He died on September 7, 1990, at the age of 84, in a nursing home in London.

Works

- The Italian Problem in European Diplomacy, 1847–1849, 1934.

- (editor) The Struggle for Supremacy in Germany, 1859–1866 by Heinrich Friedjung, 1935.

- Germany's First Bid for Colonies 1884–1885: a Move in Bismarck's European Policy, 1938.

- The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918, 1941, revised edition 1948, reissued in 1966 .

- The Course of German history: a Survey of the Development of Germany since 1815, 1945. Reissued in 1962.

- Trieste, (London: Yugoslav Information Office, 1945). 32 pages.

- Co-edited with R. Reynolds British Pamphleteers, 1948.

- Co-edited with Alan Bullock A Select List of Books on European History, 1949.

- From Napoleon to Stalin, 1950.

- Rumours of Wars, 1952.

- The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918 (Oxford History of Modern Europe), 1954.

- Bismarck: the Man and Statesman, 1955. Reissued by Vintage Books in 1967 .

- Englishmen and Others, 1956.

- co-edited with Sir Richard Pares Essays Presented to Sir Lewis Namier, 1956.

- The Trouble Makers: Dissent over Foreign Policy, 1792–1939, 1957.

- Lloyd George, 1961.

- The Origins of the Second World War, 1961. Reissued by Fawcett Books in 1969 .

- The First World War: an Illustrated History, 1963. American edition has the title: Illustrated history of the First World War.

- Politics in Wartime, 1964.

- English History 1914–1945 (Volume XV of the Oxford History of England), 1965.

- From Sarajevo to Potsdam, 1966. 1st American edition, 1967.

- From Napoleon to Lenin, 1966.

- The Abdication of King Edward VIII by Lord Beaverbrook, (editor) 1966.

- Europe: Grandeur and Decline, 1967.

- Introduction to 1848: The Opening of an Era by F. Fejto, 1967.

- War by Timetable, 1969. ISBN: 0-356-02818-6

- Churchill Revised: A Critical Assessment, 1969.

- (editor) Lloyd George: Twelve Essays, 1971.

- (editor) Lloyd George: A Diary by Frances Stevenson, 1971. ISBN: 0091072700

- Beaverbrook, 1972. ISBN: 0-671-21376-8

- (editor) Off the Record: Political Interviews, 1933–43 by W. P. Corzier, 1973.

- A History of World War Two: 1974.

- "Fritz Fischer and His School," The Journal of Modern History Vol. 47, No. 1, March 1975

- The Second World War: an Illustrated History, 1975.

- The Last of Old Europe: a Grand Tour, 1976. Reissued in 1984. ISBN: 0-283-99170-4

- Essays in English History, 1976. ISBN: 0-14-021862-9

- "Accident Prone, or What Happened Next," The Journal of Modern History Vol. 49, No. 1, March 1977

- The War Lords, 1977.

- The Russian War, 1978.

- How Wars Begin, 1979. ISBN: 0-689-10982-2

- Politicians, Socialism, and Historians, 1980.

- Revolutions and Revolutionaries, 1980.

- A Personal History, 1983.

- An Old Man's Diary, 1984.

- How Wars End, 1985.

- Letters to Eva: 1969–1983, edited by Eva Haraszti Taylor, 1991.

- From Napoleon to the Second International: Essays on Nineteenth-century Europe. Ed. 1993.

- From the Boer War to the Cold War: Essays on Twentieth-century Europe. Ed. 1995. ISBN: 0-241-13445-5

- Struggles for Supremacy: Diplomatic Essays by A.J.P. Taylor. Edited by Chris Wigley. Ashgate, 2000. ISBN: 1-84014-661-3

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: A. J. P. Taylor para niños

In Spanish: A. J. P. Taylor para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |