History of Italy facts for kids

Italy is a European country with a very long history. People have lived there for at least 850,000 years! Over time, many different groups made Italy their home. These included the ancient Etruscans, various Italic peoples like the Latins, Celts, and Greek colonists from Magna Graecia.

Ancient Italy was the homeland of the Romans. Rome started as a kingdom in 753 BC and became a republic in 509 BC. The Roman Republic then united Italy and grew to rule much of Western Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. After the assassination of Julius Caesar, the Roman Empire took over. It lasted for centuries, shaping Western culture, ideas, science, and art.

After the fall of Rome in AD 476, Italy broke into many small city-states and regions. This lasted until the country was fully united in 1871. Important trading cities like Venice and Genoa became very rich. Central Italy was ruled by the Papal States (the Pope's lands). Southern Italy was often ruled by different foreign powers like the Byzantines, Arabs, Normans, and Spanish.

The Italian Renaissance was a time of great change. It brought new interest in humanism, science, exploration, and art. This period spread across Europe and marked the start of the modern age.

In the mid-1800s, Giuseppe Garibaldi helped unite Italy. With support from the Kingdom of Sardinia, a single Italian nation was formed. The new Kingdom of Italy quickly modernized and built a colonial empire in Africa and around the Mediterranean. However, Southern Italy remained poor, leading many people to move away in the Italian diaspora.

Italy joined World War I and gained more land, completing its unification. It also got a permanent seat in the League of Nations. But its involvement in World War II ended in defeat. After the war, Italy became a republic in 1946. It then had an economic boom and helped found the European Union, NATO, and the G7.

Contents

- Ancient Beginnings: Prehistory and Early Civilizations

- Iron Age: Etruscans, Italics, and Greeks

- Roman Period: From Republic to Empire

- Middle Ages: Fragmentation and City-States

- Renaissance: A Rebirth of Art and Ideas

- From Counter-Reformation to Napoleon: Foreign Control and Change

- Unification (1814–1861): The Risorgimento

- Liberal Period (1861–1922): A New Kingdom

- Fascist Regime, World War II, and Civil War (1922–1946)

- Republican Era (1946–present): Modern Italy

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Beginnings: Prehistory and Early Civilizations

Prehistoric Italy: First Humans and Early Cultures

The first humans arrived in Italy about 850,000 years ago. Evidence of Neanderthals has been found near Rome and Verona, dating back about 50,000 years. Modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) appeared later, during the Stone Age. Famous ancient finds include stone carvings in Valcamonica and the well-preserved body of Ötzi the Iceman, from about 3400–3100 BC.

During the Copper Age, people from other parts of Europe moved into Italy. They brought new skills like working with copper. Later, in the Bronze Age, more groups arrived, bringing bronze tools and new ways of life. These groups included the Beaker culture and the Terramare culture. The Terramare people hunted, farmed, and were skilled at working with bronze.

In the late Bronze Age, around 1000 BC, the Proto-Villanovan culture brought iron-working to Italy. This culture is linked to the arrival of the early Italic languages.

Nuragic Civilization: Sardinia's Ancient Towers

The Nuragic civilization grew in Sardinia and southern Corsica. It lasted from about 1800 BC until the islands became part of the Roman Empire. This civilization is famous for its unique stone towers called nuraghes. More than 7,000 of these towers can still be seen in Sardinia today.

We don't have many written records from this civilization. Most of what we know comes from ancient Greek and Roman stories, which are often more like myths. The language they spoke is also a mystery.

-

Monte d'Accoddi, a large stone structure from the 4th millennium BCE.

-

The Giants of Mont'e Prama, ancient stone statues.

-

A bronze sculpture of a Nuragic chief from Uta.

Iron Age: Etruscans, Italics, and Greeks

Etruscan Civilization: Masters of Central Italy

The Etruscan civilization became powerful in central Italy after 800 BC. They likely developed from an earlier local culture. The Etruscans had a form of state, with leaders and tribal traditions. Their religion believed that gods were present in everything around them.

Etruscans expanded their influence through trade, especially in copper and iron. This made them rich and powerful in Italy and the western Mediterranean. They sometimes clashed with the Greeks who were also settling in the area. Around 540 BC, a sea battle with the Greeks changed the balance of power.

By the 5th century BC, the Etruscans began to decline. Their allies, the Carthaginians, were defeated by Greek cities. Later, the Romans and Samnites took over their southern lands. In the 4th century BC, a Gallic invasion weakened their control in the north. Slowly, Rome began to take over Etruscan cities, and by 500 BC, Etruscan culture was absorbed by Rome.

-

The Necropolis of Banditaccia in Cerveteri, an ancient Etruscan burial ground.

Italic Peoples: Tribes of the Peninsula

The Italic peoples were groups who spoke Italic languages, part of the larger Indo-European language family. Important Italic groups in Italy included the Osci, Veneti, Samnites, Latins, and Umbri.

In central Italy, the Latins developed their own culture. In the northeast, the Veneti had a distinct culture. Other groups like the Osco-Umbrians spread across the southern part of the peninsula. Sicily was also home to native Italic tribes like the Elymians, Sicani, and Sicels.

By the middle of the first millennium BC, the Latins of Rome became very powerful. After freeing themselves from Etruscan rule, they became the leading Italic tribe. They fought many wars, including the Samnite Wars, and eventually united the Italic peoples. In the early 1st century BC, some Italic tribes rebelled against Roman rule in the Social War. After Rome won, all people in Italy (except the Celts in the Po Valley) were granted Roman citizenship. Over time, these Italic tribes adopted the Latin language and Roman culture.

Magna Graecia: Greek Colonies in Southern Italy

In the 8th and 7th centuries BC, Greeks began to settle in Southern Italy. They were looking for new trade routes and places to live. They brought their Greek culture, language, religious practices, and independent city-states (polis) with them. This led to the growth of a unique Greek civilization in Italy, which later mixed with native Italic and Roman cultures.

One of the most important things the Greeks brought was their alphabet. The Chalcidean/Cumaean Greek alphabet was adopted by the Etruscans. This alphabet then developed into the Latin alphabet, which is now used all over the world.

Many of these new Greek cities became very rich and powerful. Some famous ones include Neapolis (Naples), Syracuse, Acragas, and Sybaris. After a war where Pyrrhus of Epirus tried to stop Rome, Southern Italy came under Roman control around 282 BC.

Roman Period: From Republic to Empire

Roman Kingdom: The Legendary Beginnings

We don't know much for sure about the early Roman Kingdom. Most stories come from legends written much later. According to myth, Rome was founded on April 21, 753 BC, by twin brothers Romulus and Remus. They were said to be descendants of the Trojan prince Aeneas. Rome's location was good because it had a place to cross the Tiber River and hills that were easy to defend.

Tradition says Rome was ruled by seven kings. However, modern historians don't believe this timeline is fully accurate. Many early Roman records were destroyed when the Gauls attacked Rome in 390 BC. So, stories about the kings must be looked at carefully.

Roman Republic: Growth and Power

The Roman Republic was formed around 509 BC. This happened when the last king, Tarquin the Proud, was removed. Rome then set up a system with elected leaders and different assemblies. A constitution created a system of checks and balances to prevent any one person from having too much power. The most important leaders were two consuls, who shared executive power and military command. They worked with the senate, which was a council of important noble families.

In the 4th century BC, the Gauls attacked Rome and even sacked the city. But the Romans fought back and drove them out. Rome then slowly took control of other peoples on the Italian peninsula. The last major challenge to Roman rule in Italy came from Pyrrhus of Epirus in 281 BC, but his efforts failed.

In the 3rd century BC, Rome faced a powerful enemy: Carthage. After three long Punic Wars, Rome defeated Carthage. This gave Rome control over Spain, Sicily, and North Africa. By the 2nd century BC, Rome had also defeated the Macedonian and Seleucid Empires, becoming the most powerful force in the Mediterranean Sea. Roman culture began to mix with Greek culture, making the Roman elite more sophisticated.

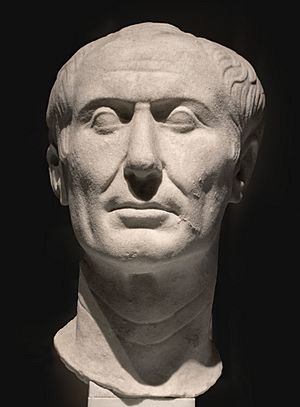

By the mid-1st century BC, the Republic faced political problems and social unrest. This is when Julius Caesar became very important. He formed an alliance with two other powerful men, Marcus Licinius Crassus and Pompey. After Crassus died, Caesar and Pompey became rivals. After winning the Gallic Wars, Caesar marched his army into Rome in 49 BC and quickly defeated Pompey. Caesar was made dictator for life, but he was murdered in 44 BC.

Caesar's death led to more chaos. His adopted son, Octavian, formed an alliance with Mark Antony and Lepidus. After some power struggles, Octavian defeated Mark Antony and his ally Cleopatra in the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. This gave Rome complete control of the seas.

Roman Empire: A Golden Age and Decline

Octavian's leadership brought a golden age to Rome, lasting for 40 years. When he took the name Augustus in 27 BC, it marked the start of the Roman Empire. Officially, Rome was still a republic, but Augustus held all the real power. He controlled the army and the most important provinces.

Roman Italy had a special status. It was considered the "ruler of the provinces" and the "parent of all lands." People in Italy had special rights and privileges. Under Augustus, Roman literature flourished with famous poets like Vergil and Horace. This peaceful and prosperous time, lasting 200 years, is known as the Pax Romana.

The Empire didn't expand much after Augustus, except for the conquest of Britain and Dacia. Roman armies also fought against Germanic tribes and the Parthian Empire. There were also some rebellions and civil wars within the Empire.

After Emperor Theodosius I died in 395 AD, the Empire split into an Eastern and a Western Roman Empire. The Western part faced many problems, including economic crises and constant invasions from barbarian tribes. In 476 AD, the last Western Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was removed from power.

Middle Ages: Fragmentation and City-States

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Italy was ruled by the Ostrogoths. Later, the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire tried to take control, leading to a devastating war. This allowed another Germanic tribe, the Lombards, to take over large parts of Italy. In 751, the Lombards ended Byzantine rule in northern Italy.

The Pope then asked the Franks for help. In 756, Frankish forces defeated the Lombards and gave the Pope control over much of central Italy, creating the Papal States. In 800, Charlemagne, the Frankish king, was crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. After his death, the empire weakened, and Italy faced attacks from Arab forces in the south. In the north, cities began to gain more power.

By the 11th century, trade started to recover, and cities grew again. The Pope also regained his authority. In the north, a group of cities called the Lombard League fought for and won their independence from the Holy Roman Empire. In the south, the Normans conquered both Lombard and Byzantine lands.

The Normans also ended Muslim rule in Sicily. In 1130, Roger II of Sicily became the first king of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily. This kingdom had a strong central government.

Between the 12th and 13th centuries, Italy developed a unique political system. Instead of powerful kingdoms, many independent city-states emerged. These cities, like Florence, Genoa, and Venice, became rich through trade. This freedom helped lead to the artistic and intellectual changes of the Renaissance.

These cities became major financial and commercial centers. They developed new banking methods and economic organizations. The Maritime Republics (sea-faring republics) like Venice and Genoa built strong navies and controlled much of the trade with the East.

Central and southern Italy were generally poorer. Rome was in ruins, and the Papal States were not well-governed. Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia were often under foreign rule. The Black Death in 1348 caused a terrible blow, killing a large part of the population.

-

The Emirate of Sicily (831–1072).

Renaissance: A Rebirth of Art and Ideas

After the Black Death, Italy's cities, trade, and economy bounced back. Italy became the main center of the Renaissance, a "rebirth" of arts, architecture, literature, science, and political ideas that spread across Europe. This was fueled by rediscovering ancient texts and Greek scholars moving to Italy after the fall of Constantinople.

The Italian Renaissance started in Florence, a city in Tuscany. It then spread to other cities like Rome. The Tuscan dialect of Italian became very important in Renaissance literature. Famous writers like Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio lived during this time. Italian Renaissance painting and Renaissance architecture greatly influenced European art.

The Aldine Press in Venice created new ways of printing books, making them smaller and cheaper. Important thinkers like Niccolò Machiavelli wrote books that shaped modern philosophy and politics.

The Renaissance was also a time of great economic growth. Venice and Genoa were leaders in trade, followed by Milan and Florence. They developed new financial tools like tradeable bonds. Venice became the first true international financial center.

Age of Discovery: Italian Explorers

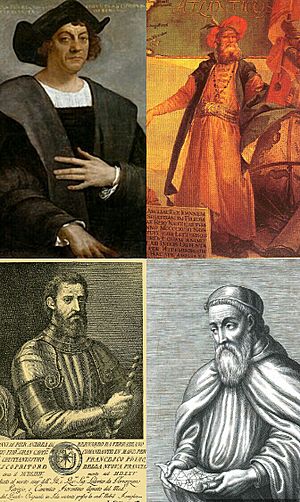

Italian explorers and sailors from the powerful maritime republics played a key role in the Age of Discovery. They wanted to find new routes to Asia to avoid the Ottoman Empire. Some of the most famous explorers were:

- Christopher Columbus: He sailed for Spain and is credited with discovering the New World.

- John Cabot: Sailing for England, he was the first European to explore parts of North America in 1497.

- Amerigo Vespucci: Sailing for Portugal, he showed that the New World was a new continent, not Asia. America is named after him!

- Giovanni da Verrazzano: Working for France, he explored the Atlantic coast of North America in 1524.

Warfare: Conflicts and Foreign Rule

In the 14th century, Northern Italy was divided into many warring city-states like Milan, Florence, and Venice. These states often fought each other, using armies of hired soldiers called condottieri. By the 15th century, the most powerful city-states began to take over their smaller neighbors.

After decades of fighting, Florence, Milan, and Venice became the main powers. They signed the Peace of Lodi in 1454, which brought peace to the region for about 40 years. At sea, Venice became the most powerful after long conflicts with Genoa.

However, the Italian Wars began in 1494 with an invasion by France. These wars brought widespread destruction to Northern Italy and ended the independence of many city-states. The wars became a struggle for power among many European countries. Eventually, the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559 ended French claims in Italy. This began a long period where the Habsburg family (from Austria and Spain) controlled much of Italy.

The Sack of Rome in 1527 by German mercenaries was a terrible event. It greatly reduced the Pope's role as a patron of Renaissance art. Many Italian cities suffered from invasions, high taxes, and economic decline.

From Counter-Reformation to Napoleon: Foreign Control and Change

The 17th century was a difficult time for Italy. The Pope's power grew, and the Catholic Church was very influential during the Counter Reformation (its response to the Protestant Reformation). Most of Italy was under foreign control. The north was influenced by the Austrian Habsburgs, and the south was directly ruled by the Spanish Habsburgs.

Despite some artistic and scientific achievements, like those of Galileo and the flourishing of the Baroque style, Italy's economy struggled after 1600. It went from being an advanced industrial area to an economically backward region. Wars, political divisions, and the shift of world trade towards the Atlantic (after the discovery of the New World) all contributed to this decline. Spain's wars also drained Italy's resources.

Plagues in 1630 and 1656 killed many people, further hurting Italy's economy and population.

18th Century: Shifting Powers

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) changed who controlled parts of Italy. Control of Milan, Naples, and Sardinia shifted from Spain to Austria. Sicily went to the Duchy of Savoy. Later, Spain tried to regain territories but was defeated. The Duchy of Savoy exchanged Sicily for Sardinia and became the King of Sardinia. Spain eventually regained Naples and Sicily in 1738. Corsica was sold by Genoa to France in 1769.

Age of Napoleon: French Influence and New Ideas

By the end of the 18th century, Italy was still divided and largely controlled by foreign powers, mainly Austria and Spain. In 1796, the French army led by Napoleon invaded Italy. He quickly defeated the local rulers and was welcomed by many as a liberator.

Napoleon conquered most of Italy and set up new republics. These new states had modern laws and ended old feudal privileges. For example, the Cisalpine Republic was centered in Milan, and the Roman Republic was formed from the Pope's lands. Napoleon even made himself king of the Kingdom of Italy in 1805. These new countries were linked to France and had to support Napoleon's wars. However, their political and administrative systems were modernized, and trade barriers were reduced.

The Italian tricolour (green, white, and red flag) was first officially adopted by a state in Italy during the Napoleonic era in 1797. This event is celebrated as Tricolour Day.

After Napoleon's defeat in 1814, the Congress of Vienna restored many of the old rulers and divided Italy again. Austria gained control of Lombardy and Veneto. The Kingdom of Sardinia grew, and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was restored in the south. However, the period under Napoleon had planted the idea of a united Italy. Italians had experienced better laws, fairer taxes, and more freedom. They began to feel a sense of common nationality.

Unification (1814–1861): The Risorgimento

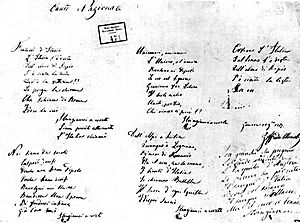

The Risorgimento was the process of uniting the different states of the Italian peninsula into a single nation. Most historians agree it started after Napoleon's rule ended in 1815 and largely finished with the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

In the 1820s, revolutionary movements began to appear. In the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, a military regiment rebelled, forcing the king to agree to a new constitution. However, these revolts were put down by Austrian troops. In Piedmont, a revolt aimed to remove the Austrians and unite Italy under the House of Savoy. This also failed.

Artists and writers also supported nationalism. Alessandro Manzoni's novel I Promessi Sposi helped standardize the Italian language based on the Tuscan dialect.

The main obstacle to unification was the Austrian Empire, which controlled much of northeastern Italy. Austrian Chancellor Franz Metternich famously called Italy "a geographic expression," meaning it wasn't a real country. The Pope also opposed unification, fearing he would lose power over the Papal States.

Even those who wanted unification disagreed on what kind of country it should be. Some, like the priest Vincenzo Gioberti, suggested a confederation of states led by the Pope. Many revolutionaries wanted a republic. But in the end, it was a king and his chief minister who united Italy as a monarchy.

One important secret group was the Carbonari (charcoal burners). They were inspired by the French Revolution and wanted a united Italy. They were feared by rulers, who even made it a crime punishable by death to attend their meetings. Many leaders of the unification movement were once members of this group. In 1847, the song Il Canto degli Italiani, which is now Italy's national anthem, was first performed publicly.

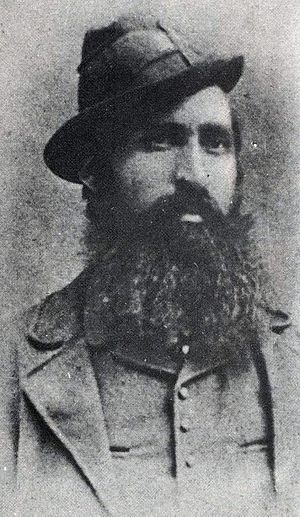

Two key figures in the unification were Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi. Mazzini believed Italy should be a free, independent republic with Rome as its capital. He founded a group called La Giovine Italia to work towards this goal. Garibaldi, a military leader, participated in revolts and later returned from South America to lead the republican efforts in southern Italy.

The Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, led by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, also wanted to unite Italy. They successfully challenged Austria in the Second Italian War of Independence, gaining Lombardy–Venetia. Piedmont-Sardinia also made alliances with countries like Britain and France.

Garibaldi led his forces to conquer southern Italy, but the northern monarchy of the House of Savoy eventually took the lead in uniting the country.

Southern Question and Italian Diaspora: Challenges After Unification

The unification was not easy for Southern Italy, known as the "Mezzogiorno." There was a big difference between the North and South. The South faced many economic and social problems. Transportation was difficult, soil was poor, and many people were unemployed.

The new government tried to fix problems by applying the Piedmontese legal system. But this led to a rise in brigandage, which became a bloody civil war lasting almost ten years. After these conflicts, millions of peasants from the South left Italy in the Italian diaspora, especially to the United States and South America. Others moved to industrial cities in the North like Genoa, Milan, and Turin.

Poverty and lack of land were the main reasons for emigration. Many farmers had very small plots of land that were not productive enough. Overpopulation in the South also contributed to this mass migration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Italians sought "work and bread" (pane e lavoro) in other countries.

The end of the feudal land system in the South did not always help small farmers. Many remained without land or with plots too small to make a living. Between 1860 and World War I, at least 9 million Italians left the country permanently.

Liberal Period (1861–1922): A New Kingdom

Italy officially became a nation-state on March 17, 1861, with Victor Emmanuel II as king. The main people who made this happen were Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour and Giuseppe Garibaldi. In 1866, Italy allied with Prussia in a war against Austria. This victory allowed Italy to annex Venice. In 1870, when France withdrew its soldiers from Rome, Italy took over the Papal States. Italian unification was complete, and Rome became the capital.

Some areas, like Trentino-Alto Adige and Julian March, did not join Italy until after World War I in 1918.

Parliamentary democracy grew in the 19th century. The Statuto Albertino of 1848 gave basic freedoms, but only wealthy and educated men could vote. Italian politics was often divided, leading to frequent changes in government. Prime Ministers like Agostino Depretis tried to keep power by making deals with different groups, a practice called Trasformismo. This often led to corruption.

Depretis introduced some important changes, like making elementary education free and compulsory. However, his government also spent too much, leaving Italy in debt. Francesco Crispi, another Prime Minister, tried to make Italy a great world power by increasing military spending and seeking alliances with Germany. He was also authoritarian but introduced some liberal policies like a Public Health Act.

The focus on foreign policy meant that agriculture was neglected. A report showed that landowners were not investing in their land, and many farmers lived in poverty. Disease, like a major cholera epidemic, spread rapidly. Italy also faced economic problems when its wine exports declined.

From 1901 to 1914, Giovanni Giolitti dominated Italian politics. He tried to calm social unrest by allowing strikes (as long as they were peaceful) and bringing socialists into political life. Giolitti introduced social and labor laws, universal male suffrage, and nationalized railways. He also improved infrastructure and industry. In foreign policy, he moved Italy closer to France, Britain, and Russia.

Italy also began to build a colonial empire, taking control of Somalia. Its attempt to conquer Ethiopia failed in 1896. In 1911, Italy invaded Libya and took it from the Ottoman Empire.

World War I and the Decline of Liberalism

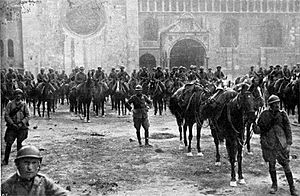

Italy entered World War I in 1915 to complete its national unity. This is sometimes called the Fourth Italian War of Independence. Italy had been neutral for six months, as its alliance with Germany and Austria was only for defense. Italy secretly negotiated with both sides to get the best deal. The Allies promised Italy large parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including Tyrol and Trieste.

When the Treaty of London was announced, many Italians were against the war. They feared the costs and cared little about new territories. However, pro-war supporters rallied, and the king's position was at risk. Benito Mussolini started a newspaper, Il Popolo d'Italia, which at first tried to convince socialists to support the war.

Italy entered the war with a large but poorly led army. Fighting was difficult, especially along the Isonzo River. Germany later joined the war against Italy. About 650,000 Italian soldiers died, and 950,000 were wounded. The economy needed a lot of money from the Allies to survive.

The government had to get involved in war production. Strikes were common, especially in industrial areas. Inflation doubled the cost of living. Despite the difficulties, Italy's victory marked the end of the war on the Italian Front.

After the war, Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando met with other Allied leaders to discuss new borders for Europe. Italy felt it didn't get enough territory, especially Dalmatia and Albania, which had been promised. This caused anger against the government. However, Italy did gain Trentino-Alto Adige and the Julian March.

Furious about the peace settlement, the nationalist poet Gabriele D'Annunzio led veterans to take over the city of Fiume in 1919. He was called Il Duce ("The Leader") and used black-shirted paramilitary groups. These ideas and symbols were later adopted by Benito Mussolini's Fascist movement. Fiume was eventually annexed to Italy in 1924.

Fascist Regime, World War II, and Civil War (1922–1946)

Rise of Fascism: Mussolini Takes Power

Benito Mussolini started the Fasci di Combattimento (Combat League) in 1919. At first, it included patriotic veterans who wanted social change and women's voting rights. They were different from later Fascism because they opposed censorship and dictatorship.

After World War I, Italy faced economic problems and political instability. There were many strikes and worker protests. The Fascists used this unrest to gain support. In October 1922, Mussolini demanded that the Fascist Party be given political power. A group of 30,000 Fascists marched to Rome (the March on Rome), claiming they would restore order.

The king, Victor Emmanuel III, faced a difficult choice between the Fascists and the Socialists. He chose the Fascists and appointed Mussolini as Prime Minister. Mussolini formed a government with other parties. In 1923, he passed a law that helped his party win more seats in Parliament. The Fascist Party used violence to control the 1924 election.

A Socialist leader, Giacomo Matteotti, was murdered after he spoke out against Fascist violence. Over the next four years, Mussolini removed almost all limits on his power. He became responsible only to the king and controlled Parliament's agenda. Local governments were replaced by appointed officials. In 1928, all other political parties were banned. Mussolini created a strong cult of personality around himself.

Historians describe Fascism in Italy as a political dictatorship. Big businesses and the military kept some independence. The justice system and police were largely controlled by the state, not just the party. The Church also remained somewhat independent. The regime was not as violent or repressive as some other dictatorships of the time.

End of the Roman Question: Peace with the Vatican

During Italy's unification in the 1800s, the Papal States (the Pope's lands) were taken over by the new Italian nation. This created a conflict known as the "Roman Question" between the Pope and the Italian government.

The Lateran Treaty of 1929 solved this problem. It was an agreement between the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy See (the Pope's government). The treaty recognized Vatican City as an independent state ruled by the Holy See. Italy also paid the Catholic Church for the loss of the Papal States. This treaty was later included in the Constitution of Italy in 1948.

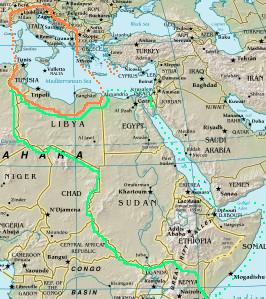

Foreign Politics: Building an Empire

Mussolini's foreign policy had three main goals: 1. Continue the goals of earlier Italian governments, like having influence in the Balkans and North Africa. 2. Overcome disappointment from World War I, where Italy felt it didn't gain enough. 3. Restore the glory of the Roman Empire.

Italian Fascism was based on nationalism. It wanted to complete the unification of Italy by taking over areas with Italian populations that were not yet part of Italy. These included parts of Dalmatia, Malta, Corsica, Nice, and Savoy.

Mussolini promised to make Italy a great power in Europe and control the Mediterranean Sea, which he called "Mare Nostrum" (Our Sea). In 1923, Italy briefly occupied the Greek island of Corfu. In 1925, Albania came under strong Italian influence.

Italy's relationship with France was complicated. The Fascist regime wanted to regain Italian-speaking areas from France. With the rise of Nazism in Germany, Italy became worried about German expansion. Italy joined the Stresa Front with France and the United Kingdom to oppose Germany.

During the Spanish Civil War, Italy sent troops and weapons to help the Nationalists led by Francisco Franco. This increased Italy's influence in the Mediterranean. By 1940, the Italian navy was the fourth largest in the world.

Mussolini and Adolf Hitler first met in 1934. Publicly, they showed a close relationship, but they were also rivals for world influence. In 1935, Mussolini invaded Ethiopia. This led to Italy's international isolation, with only Nazi Germany supporting the aggression. Italy left the League of Nations in 1937.

Mussolini reluctantly joined Hitler in international politics. He supported Germany's annexation of Austria in 1938 and its claims on Sudetenland. Under Hitler's influence, Italy also adopted anti-Jewish laws. In March 1939, Italy invaded Albania and made it a protectorate.

As war approached in 1939, Italy increased its demands against France. In May 1939, Italy signed a formal alliance with Germany, called the Pact of Steel. Mussolini felt forced to sign it, even though he knew Italy was not ready for war. He was also upset when Germany and the Soviet Union agreed to divide Poland.

World War II and the Fall of Fascism

When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, starting World War II, Mussolini chose to stay neutral at first. He planned for Italy to annex large parts of Africa and the Middle East. Mussolini waited until France was invaded by Germany in June 1940 before deciding to join the war.

Italy entered the war on June 10, 1940. Mussolini hoped to quickly take French territories like Savoy, Nice, Corsica, and colonies in Tunisia and Algeria. However, Germany signed an armistice with France, which angered the Fascist regime. Italy then bombed Palestine and conquered British Somaliland. In September, Italy invaded Egypt, but its forces were pushed back by the British. Hitler had to send German troops to help in North Africa.

On October 28, Mussolini attacked Greece. The British Royal Air Force helped the Greeks push the Italians back. Hitler again came to Mussolini's aid, attacking Greece through the Balkans. This led to the breakup of Yugoslavia and Greece's defeat. Italy gained some territories and set up puppet states.

By 1942, Italy's war effort was failing. Its economy struggled, and Italian cities were heavily bombed by the Allies. The North African campaign also began to fail. The final collapse came after a major defeat at El Alamein.

By 1943, Italy was losing on all fronts. Many Italian soldiers had died in the Soviet Union, and the African campaign had failed. Italians wanted the war to end. In July 1943, the Allies invaded Sicily. On July 25, Mussolini was removed from power and arrested by order of King Victor Emmanuel III. General Pietro Badoglio became the new Prime Minister. Badoglio banned the Fascist Party and signed an armistice with the Allies.

Historians note that Italy's military and Fascist regime were not effective in war. This was due to problems with military culture, institutions, and equipment.

Civil War, Allied Advance, and Liberation

After Mussolini was removed, German commandos rescued him. The Germans took Mussolini to northern Italy, where he set up a Fascist puppet state called the Italian Social Republic (RSI). Meanwhile, the Allies advanced in southern Italy. In September 1943, Naples rose up against the German forces.

The Allies organized some Italian royalist troops into the Italian Co-Belligerent Army. Other Italian troops continued to fight with Nazi Germany. A large Italian resistance movement began a long guerrilla war against German and Fascist forces. The Germans, often helped by Fascists, committed many atrocities against Italian civilians. The Kingdom of Italy declared war on Nazi Germany on October 13, 1943.

On June 4, 1944, the German occupation of Rome ended as the Allies advanced. The final Allied victory in Italy came in the spring of 1945. German and Fascist forces in Italy surrendered on May 2, just before World War II ended in Europe.

During World War II, Italian forces also committed war crimes, including killings and forced deportations. After the war, Yugoslav Partisans also committed crimes against ethnic Italians.

On April 25, 1945, the National Liberation Committee for Northern Italy called for a general uprising against the Nazis. This day is now celebrated as Liberation Day in Italy. Mussolini was captured on April 27, 1945, and executed the next day. German forces in Italy surrendered on May 2, 1945.

After the war, several interim governments led Italy. Finally, Alcide de Gasperi oversaw the transition to a Republic. King Victor Emmanuel III abdicated, and his son Umberto II reigned for only a month. A referendum then abolished the monarchy.

Anti-Fascism: Resistance to Mussolini's Rule

In Italy, Mussolini's Fascist regime called its opponents "anti-fascists." The secret police was called the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism (OVRA). In the 1920s, anti-fascists, many from labor movements, fought against the violent Fascist Blackshirts.

Some anti-fascist groups, like Arditi del Popolo, formed to fight back. However, major labor unions and the Communist Party often chose non-violent strategies. Italian liberal anti-fascists like Benedetto Croce wrote against the regime.

The Concentrazione Antifascista Italiana was a group of anti-Fascist organizations that worked to coordinate actions from outside Italy. Giustizia e Libertà (Justice and Freedom) was another important anti-Fascist resistance movement. It actively opposed Fascism and informed the world about the realities of the regime.

In territories annexed by Italy after World War I, like the Julian March, anti-Fascist movements were active among Slovenes and Croats. The group TIGR carried out sabotage and attacks. Many members of the Italian resistance later fought against Italian Fascists and German Nazi soldiers during the Italian Civil War. Many Italian cities were freed by anti-Fascist uprisings.

Republican Era (1946–present): Modern Italy

Birth of the Republic: A New Beginning

After World War II, Italy's economy was destroyed, and society was divided. Many people were angry at the monarchy for supporting the Fascist regime. This led to a strong movement for Italy to become a republic. On June 2, 1946, a referendum was held, and 54% of voters chose for Italy to become a republic.

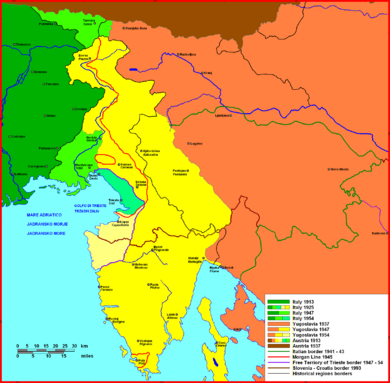

Under the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947, Italy lost some territories, including Istria and most of the Julian March, which were annexed by Yugoslavia. This caused many ethnic Italians to leave their homes. Italy also lost all its colonial possessions. The current Italian border was finalized in 1975 when Trieste was formally returned to Italy.

In the 1946 elections, a Constituent Assembly was elected to write a new constitution. It set up a parliamentary democracy. In 1947, communists were removed from the government. The 1948 elections saw a big win for the Christian Democrats, who dominated Italian politics for the next 40 years.

Italy joined the Marshall Plan (a US aid program) and NATO. By 1950, the economy had stabilized and began to grow rapidly. In 1957, Italy was a founding member of the European Economic Community (EEC), which later became the EU. The Marshall Plan helped modernize Italy's economy, leading to a big increase in industrial production.

Economic Miracle: A Time of Growth

In the 1950s and 1960s, Italy experienced a long period of economic growth, known as the Italian economic miracle. This led to a big improvement in the standard of living for ordinary Italians. The economy grew by an average of 5-6% per year.

Millions of people moved within Italy during this time, especially to the industrial cities of Milan, Turin, and Genoa. The growing economy needed new transport and energy systems. Thousands of kilometers of railways and highways were built. However, this rapid growth sometimes happened without enough care for the environment.

Years of Lead: Political Violence

The 1970s saw a rise in political violence in Italy, known as the Years of Lead. There were terrorist attacks by both far-right and far-left groups. For example, the Piazza Fontana bombing in 1969 and attacks by the Red Brigades. The assassination of Christian Democracy leader Aldo Moro in 1978 was a major event.

In the 1980s, for the first time, governments were led by parties other than the Christian Democrats, such as the Republican and Socialist parties.

Second Republic (1992–present): Modern Challenges

Italy faced several terrorist attacks by the Sicilian Mafia between 1992 and 1993. These attacks were a response to anti-mafia efforts by the government. They caused deaths and damage to cultural sites.

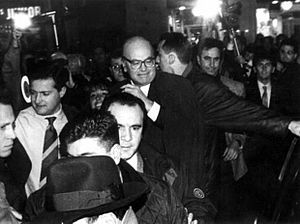

From 1992 to 1997, Italy faced major challenges. Voters were unhappy with political problems, huge government debt, widespread corruption, and the influence of organized crime. This period is known as Tangentopoli (Bribesville). Many politicians were investigated, and major political parties dissolved.

In the 1994 election, media businessman Silvio Berlusconi became Prime Minister. He led a center-right coalition. After some changes in government, Berlusconi regained power in 2001 and served a full five-year term, the longest in post-war Italy. He supported the US-led war in Iraq.

In 2006, Romano Prodi led a center-left coalition back to power. Berlusconi won again in 2008. Italy was hit hard by the Great Recession of 2008–09 and the later European debt crisis. In 2011, Berlusconi resigned, and economist Mario Monti led a government focused on austerity measures to reduce debt.

In 2013, a new election led to a coalition government. Later, Matteo Renzi became Prime Minister and introduced many reforms, including changes to the electoral system and labor laws. He also introduced same-sex civil unions. However, Renzi resigned after losing a referendum in 2016.

The 2018 election resulted in a hung parliament, leading to a populist government led by Giuseppe Conte. In 2020, Italy was severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Conte's government imposed a national lockdown. The pandemic caused many deaths and severe economic problems. In 2021, a national coalition government was formed, led by former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi.

In 2022, a government crisis led to a snap election. The center-right coalition won, and Giorgia Meloni became Italy's first female prime minister on October 22, 2022.

Images for kids

-

The Sassi cave houses of Matera are believed to be among the first human settlements in Italy dating back to the Paleolithic.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Italia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Italia para niños

- Duchy of Urbino

- Genetic history of Italy

- History of Capri

- History of Naples

- History of Rome

- History of Sardinia

- History of Sicily

- History of the Republic of Venice

- History of Trentino

- History of Tuscany

- History of Verona

- Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia

- List of consorts of Montferrat

- List of consorts of Naples

- List of consorts of Savoy

- List of consorts of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

- List of consorts of Tuscany

- List of Italian queens

- List of Italian inventions and discoveries

- List of kings of the Lombards

- List of Milanese consorts

- List of Modenese consorts

- List of monarchs of Naples

- List of monarchs of Sardinia

- List of monarchs of Sicily

- List of monarchs of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

- List of Parmese consorts

- List of presidents of Italy

- List of prime ministers of Italy

- List of queens of the Lombards

- List of Roman and Byzantine Empresses

- List of rulers of Tuscany

- List of Sardinian consorts

- List of Sicilian consorts

- List of State Archives of Italy

- List of viceroys of Naples

- List of viceroys of Sicily

- Milan

- Military history of Italy

- Politics of Italy

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |