Benedetto Croce facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

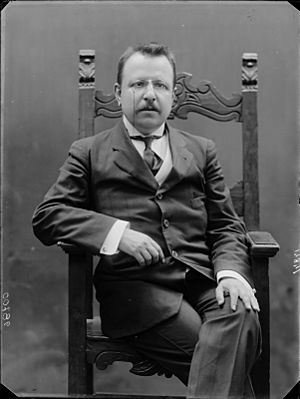

Benedetto Croce

KOCI, COSML

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the Senate of the Republic | |

| In office 8 May 1948 – 20 November 1952 |

|

| Constituency | Naples |

| Member of the Constituent Assembly of Italy | |

| In office 25 June 1946 – 31 January 1948 |

|

| Constituency | At-large |

| Minister of Public Education | |

| In office 15 June 1920 – 4 July 1921 |

|

| Prime Minister | Giovanni Giolitti |

| Preceded by | Andrea Torre |

| Succeeded by | Orso Mario Corbino |

| Member of the Senate of the Kingdom of Italy | |

| In office 26 January 1910 – 24 June 1946 |

|

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 February 1866 Pescasseroli, Italy |

| Died | 20 November 1952 (aged 86) Naples, Italy |

| Political party | PLI (1922–1952) |

| Spouse |

Adele Rossi

(m. 1914; died 1952) |

| Domestic partner |

Angelina Zampanelli

(m. 1893; her d. 1913) |

| Children | Elena, Alda, Silvia, Lidia |

| Alma mater | University of Naples |

| Profession | Historian, writer, landowner |

| Signature | |

|

Philosophy career |

|

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy

|

| School | Neo-Hegelianism Classical liberalism< Historism (storicismo) |

|

Main interests

|

History, aesthetics, politics |

|

Notable ideas

|

Liberism Aesthetic expressivism |

|

Influenced

|

|

Benedetto Croce (born February 25, 1866 – died November 20, 1952) was an important Italian thinker. He was a philosopher, a historian, and a politician. He wrote many books and articles about different topics like philosophy, history, and art.

Croce was a liberal thinker. This means he believed in individual freedom and limited government. He was also the president of PEN International, a group for writers around the world, from 1949 to 1952. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature sixteen times. Many people say he helped bring back democracy in Italy.

Contents

Who Was Benedetto Croce?

Early Life and Education

Benedetto Croce was born in a town called Pescasseroli in Italy. His family was well-known and had a lot of money. He grew up in a very strict Catholic home. However, when he was about 16, he decided to follow his own spiritual path. He believed that religion was a way for people to show their creative power. He kept this belief throughout his life.

In 1883, a big earthquake hit the island of Ischia, where he was on vacation with his family. Their home was destroyed. Sadly, his mother, father, and only sister died. Benedetto was trapped for a long time but managed to survive. After this tragedy, he inherited his family's wealth. This allowed him to spend his life studying philosophy and writing from his home in Naples.

He studied law at the University of Naples but did not finish his degree. He spent a lot of time reading about how history and society change. His ideas became known at the University of Rome in the late 1890s. Croce was friends with many European socialist thinkers.

Philosophical Influences

Croce was greatly influenced by Gianbattista Vico, a philosopher from Naples who wrote about art and history. Croce even bought the house where Vico had lived. His friend, the philosopher Giovanni Gentile, encouraged him to read the works of Hegel, another famous philosopher. Croce's well-known book about Hegel, What is Living and What is Dead of the Philosophy of Hegel, was published in 1907.

Croce's Role in Politics

Becoming a Senator and Minister

As Benedetto Croce became more famous, he was asked to get involved in politics, even though he didn't want to at first. In 1910, he became a member of the Italian Senate. This was a position he held for life. He openly disagreed with Italy joining World War I. While this made him unpopular at first, his good reputation returned after the war.

From 1920 to 1921, he served as the Minister of Public Education. This was under the government led by Giovanni Giolitti. After Croce left this role, Benito Mussolini came to power. Mussolini's first Minister of Public Education was Giovanni Gentile, who had worked with Croce before. Gentile started big changes to Italian education, partly based on Croce's earlier ideas. These changes lasted for a long time, even after the Fascist government ended.

In 1923, Croce also helped move the Biblioteca Nazionale Vittorio Emanuele III (a national library) to the Royal Palace in Naples.

Standing Up to Fascism

At first, Croce supported Mussolini's Fascist government, which took power in 1922. However, when a socialist politician named Giacomo Matteotti was killed by Fascists in June 1924, Croce's support for Mussolini ended. In May 1925, Croce was one of the people who signed the Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals. Croce himself wrote this important document.

Croce became one of the strongest opponents of fascism. In 1928, he voted against a law that took away free elections in Italy. He was upset that many former supporters of democracy had given up their beliefs. Croce often helped anti-Fascist writers and people who disagreed with the government by giving them money. He also secretly helped them publish their work. His home became a meeting place for anti-Fascists.

Mussolini's government saw Croce as a threat. Although he was never put in prison because of his fame, he was watched closely. The government also tried to hide his academic work. No major newspaper or academic journal mentioned him.

When Mussolini's government started policies against Jewish people in 1938, Croce was the only non-Jewish intellectual who refused to fill out a government form asking about people's "racial background." He also wrote in his magazine and made public statements against the persecution of Jewish people.

Post-War Government Roles

In 1944, when democracy returned to Southern Italy, Croce became a minister in the government for short periods. He was seen as a symbol of liberal anti-fascism. He was president of the Liberal Party until 1947.

Croce voted for the Monarchy in the 1946 Italian vote about the country's future. He was elected to the Constituent Assembly, which helped create Italy's new constitution. He spoke against the peace treaty signed in 1947, saying it was humiliating for Italy. He also refused to become the temporary President of Italy.

Croce's Philosophical Ideas

Understanding the Philosophy of Spirit

Croce's main philosophical ideas are found in his books: Aesthetic (1902), Logic (1908), and Philosophy of the Practical (1908). He wrote over 80 books and published in his own magazine, La Critica, for 40 years.

Croce believed that everything is connected in a spiritual way. He called his ideas the "Philosophy of Spirit." He also used terms like "absolute idealism" or "absolute historicism." Croce tried to solve problems between different ways of thinking, focusing on human experience in specific times and places. He believed that art was very important because it was at the core of human experience.

How the Mind Works

Croce divided how the mind works into different parts:

- Theoretical: This part deals with understanding things. It includes:

* Aesthetic: This is about beauty, feelings, and imagination. It includes our first ideas and how we understand history. * Logic: This is about clear thinking, concepts, and how things relate to each other.

- Practical: This part deals with doing things. It includes:

* Economics: This is about useful things and how we get what we need. * Ethics: This is about what is good and moral.

Each of these parts of the mind is guided by a main idea: Beauty guides aesthetics, Truth guides logic, Usefulness guides economics, and Goodness guides ethics. Croce believed these ideas help us understand how we think and what we know.

Views on History

Croce greatly admired Giambattista Vico. He agreed with Vico that philosophers should be the ones to write history. In his book On History, Croce said that history is like "philosophy in motion." He believed there was no big, pre-planned design in history. He also thought that the idea of a "science of history" was not real.

Ideas About Art (Aesthetics)

Croce's book Breviario di estetica (The Essence of Aesthetics) is based on four lessons he wrote for the opening of Rice University in 1912. He couldn't go, but his lessons were read there.

In this book, Croce explains his theory of art. He thought art was more important than science or deep philosophical ideas because art helps us understand ourselves better. He believed that everything we know starts with our imagination. Art comes from this imagination and is pure imagery. All thought begins with this, and it comes before other types of thinking. An artist's job is to create the perfect image for the viewer. This is what beauty truly is: forming perfect mental images inside ourselves. Our intuition helps us create these ideas.

Croce was the first to develop the idea called aesthetic expressivism. This means that art expresses feelings, not just ideas.

Contributions to Liberal Political Thought

Croce's ideas about liberalism were different from many others. While he believed that individuals are the foundation of society, he didn't think society was just a collection of separate individuals. He supported limited government but didn't think the government's powers should be fixed and unchanging.

Croce disagreed with John Locke about freedom. Locke believed freedom was a natural right. Croce thought freedom was something earned through a continuous struggle to keep it.

Croce saw civilization as a constant effort to prevent things from becoming wild or uncivilized. He believed freedom fit perfectly with his idea of civilization because it allows people to experience life to its fullest.

Croce also didn't believe in egalitarianism, which is the idea that everyone should be equal in every way. He thought society should be led by a few people who could create truth, civilization, and beauty. He believed most citizens would benefit from these creations but might not fully understand them.

In his book Etica e politica (1931), Croce described liberalism as a way of life that rejects strict rules and welcomes different ideas. He believed in individual freedom and choice. He was against the harsh rule of fascism, communism, and the Catholic Church. While he knew that democracy could sometimes threaten individual freedom, he saw liberalism and democracy as based on the same ideas of moral equality and opposing too much authority. He also recognized the good work of Socialist parties in Italy, who fought to improve conditions for workers. He urged modern socialists to avoid dictatorial solutions.

Croce also separated liberalism from capitalism or laissez-faire economic ideas. For Croce, capitalism appeared to meet certain economic needs. He believed it could be changed or replaced if better ways were found, if it didn't promote freedom, or if economic values clashed with higher values. This meant liberalism could accept socialist ideas as long as they promoted freedom. Croce's ideas influenced Italian social democrats and the mix of liberal and socialist ideas.

Important Books by Benedetto Croce

- Historical Materialism and the Economics of Karl Marx (1900)

- Aesthetic as Science of Expression and General Linguistic (1902)

- Logic as the Science of the Pure Concept (1905)

- Philosophy of the Practical Economic and Ethic (1909)

- What is Living and What is Dead of the Philosophy of Hegel (1915)

- Theory and History of Historiography (1920)

- History of Europe in the Nineteenth Century (1933)

- History as the Story of Liberty (1938)

- Politics and Morals (1945)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Benedetto Croce para niños

In Spanish: Benedetto Croce para niños

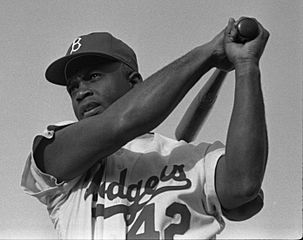

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |