Giovanni Giolitti facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Giovanni Giolitti

|

|

|---|---|

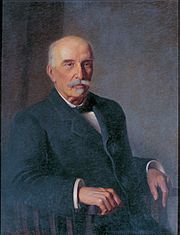

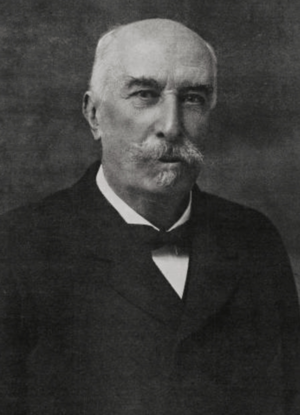

Giovanni Giolitti in 1920

|

|

| Prime Minister of Italy | |

| In office 15 June 1920 – 4 July 1921 |

|

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Francesco Saverio Nitti |

| Succeeded by | Ivanoe Bonomi |

| In office 30 March 1911 – 21 March 1914 |

|

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Luigi Luzzatti |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Salandra |

| In office 29 May 1906 – 11 December 1909 |

|

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Sidney Sonnino |

| Succeeded by | Sidney Sonnino |

| In office 3 November 1903 – 12 March 1905 |

|

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Zanardelli |

| Succeeded by | Tommaso Tittoni |

| In office 15 May 1892 – 15 December 1893 |

|

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Marchese di Rudinì |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 15 June 1920 – 4 July 1921 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Francesco Saverio Nitti |

| Succeeded by | Ivanoe Bonomi |

| In office 30 March 1911 – 21 March 1914 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Luigi Luzzatti |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Salandra |

| In office 3 November 1903 – 12 March 1905 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Zanardelli |

| Succeeded by | Tommaso Tittoni |

| In office 15 February 1901 – 20 June 1903 |

|

| Prime Minister | Giuseppe Zanardelli |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Saracco |

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Zanardelli |

| In office 15 May 1892 – 15 December 1893 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Giovanni Nicotera |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 14 September 1890 – 10 December 1890 |

|

| Prime Minister | Francesco Crispi |

| Preceded by | Federico Seismit-Doda |

| Succeeded by | Bernardino Grimaldi |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 29 May 1881 – 17 July 1928 |

|

| Constituency | Piedmont |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 October 1842 Mondovì, Kingdom of Sardinia |

| Died | 17 July 1928 (aged 85) Cavour, Piedmont, Kingdom of Italy |

| Political party | Historical Left (1882–1913) Liberal Union (1913–1922) Italian Liberal Party (1922–1926) |

| Spouses |

Rosa Sobrero

(m. 1869–1921) |

| Children | 7; including Enrichetta |

| Alma mater | University of Turin |

| Profession | |

| Signature |  |

Giovanni Giolitti (27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an important Italian politician. He served as the Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. He is the second-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history, after Benito Mussolini.

Giolitti was a leader of the Historical Left and the Liberal Union political groups. Many people consider him one of the most powerful politicians in Italian history. He was known for his ability to form flexible governments that avoided extreme political ideas. This period, from the early 1900s to the start of World War I, is often called the "Giolittian Era."

As a liberal leader, Giolitti introduced many new social reforms. These changes helped improve the daily lives of ordinary Italians. He also brought in government policies like tariffs (taxes on imported goods) and subsidies (government support for industries). He even took over private telephone and railroad companies, making them government-owned.

Giolitti aimed to govern from the middle ground, balancing conservative and progressive ideas. Some critics on the right called him a "socialist" because he worked with socialist groups. Others on the left accused him of unfair election practices. Despite these criticisms, his time in office is still debated by historians today.

Contents

- Early Life and Career

- Starting His Political Journey

- First Time as Prime Minister

- Second Time as Prime Minister

- Third Time as Prime Minister

- After Being Prime Minister

- Fourth Time as Prime Minister

- World War I

- Fifth Time as Prime Minister

- The Rise of Fascism

- Death and Lasting Impact

- The Giolittian Era

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Career

Giovanni Giolitti was born in Mondovì, a town in Piedmont, Italy, in 1842. His father passed away when Giovanni was very young. His mother, Enrichetta Plochiù, taught him to read and write.

He attended the gymnasium San Francesco da Paola in Turin. He wasn't always the best student, especially disliking math and ancient languages. Instead, he preferred history and reading novels. At 16, he started studying law at the University of Turin and earned his law degree in 1860.

Unlike many young people of his time, Giolitti was not very interested in the Risorgimento (the movement to unify Italy). He did not join the army to fight in the Italian Second War of Independence.

Working for the Government

Giolitti chose a career in public administration, working in the Ministry of Grace and Justice. This meant he didn't fight in the wars that unified Italy, which some people later criticized him for.

In 1869, he became chief secretary of the Central Tax Commission and moved to Florence. That same year, he married Rosa Sobrero. They had seven children together. In 1870, he moved to the Ministry of Finance, where he became a high-ranking official. He worked with important politicians like Quintino Sella. By 1882, he was appointed to the Council of State, a top advisory body.

Starting His Political Journey

In the 1882 Italian general election, Giolitti was elected to the Chamber of Deputies, which is like the lower house of Italy's Parliament. This election was a big win for the ruling Left party.

As a deputy, he became known for criticizing the Treasury Minister, Agostino Magliani. In 1889, Francesco Crispi, who was then Prime Minister, chose Giolitti to be the new Minister of Treasury and Finance. However, Giolitti resigned in 1890 because he disagreed with Crispi's plans for colonies.

After another government fell in 1892, King Umberto I asked Giolitti to form a new government.

First Time as Prime Minister

Giolitti's first time as Prime Minister (1892–1893) faced many challenges. There was a financial crisis and problems with state banks.

The Fasci Siciliani Movement

One major issue was the Fasci Siciliani, a popular movement in Sicily. This movement, inspired by democratic and socialist ideas, helped the poorest people on the island. They wanted new rights and better contracts for farmers.

In the summer of 1893, the movement led to widespread strikes and protests across Sicily. Landowners asked the government to step in. Giolitti tried to handle the situation calmly. He believed the government should not use force against peaceful strikes. He resigned on November 24, 1893. In the weeks that followed, violence increased, and many peasants died in clashes with the police and army.

Resignation and Comeback

A government investigation into the state banks found problems, which hurt Giolitti's political standing. He was forced to resign.

For several years, Giolitti stayed out of the spotlight. But he slowly regained his influence. He gained favor with socialist groups by promising that his government would remain neutral in labor disputes. When another government fell in 1900, Giolitti made a comeback. He strongly opposed new laws that limited public freedoms.

After the 1900 election, Giolitti became a dominant figure in Italian politics until World War I. From 1901 to 1903, he served as Italian Minister of the Interior. Many people saw him as the real power behind the Prime Minister, Giuseppe Zanardelli, who was older and in poor health.

Second Time as Prime Minister

On 3 November 1903, King Victor Emmanuel III appointed Giovanni Giolitti as Prime Minister again.

Working with Socialists

During this term, Giolitti tried to work with the left-wing and labor unions. He introduced social laws, including:

- Support for low-income housing.

- Special government contracts for worker cooperatives.

- Pensions for old age and disability.

Giolitti wanted to form an alliance with the Italian Socialist Party, which was growing quickly. He became friends with Socialist leader Filippo Turati. Giolitti even wanted Turati to join his government, but Turati always refused due to opposition from his party's left wing.

Unlike earlier leaders, Giolitti was against using force to stop labor strikes. He believed the government should act as a mediator between business owners and workers. This idea was revolutionary at the time, and conservatives strongly criticized him for it.

Resignation

Despite his efforts, Giolitti sometimes had to use strong measures to control serious unrest in Italy. This made him lose favor with some Socialists. In March 1905, he resigned, suggesting Alessandro Fortis as his replacement.

Third Time as Prime Minister

When the next Prime Minister, Sidney Sonnino, lost his majority in May 1906, Giolitti became Prime Minister for the third time. This government was known as the "long ministry."

Economic and Social Changes

Giolitti's government made important financial changes. They replaced old government bonds with new ones that had lower interest rates. This helped stabilize the country's finances. Italy's economy was strong, and its currency, the Italian lira, was very stable. This was partly due to many Italians moving abroad and sending money back home.

Giolitti's government also passed laws to protect women and child workers. These laws set limits on working hours (12 hours) and age (12 years, later 14 for some dangerous jobs). The Italian Socialist Party even supported these laws, which was rare for a Marxist group to back a "bourgeois government."

New laws also provided for a weekly day of rest and protected workers from accidents. Night work in bakeries was abolished. Laws were also passed to help poor families find affordable housing. Giolitti's government also introduced special laws to help the poorer regions of Southern Italy. These measures aimed to improve the lives of farmers in the south.

1908 Messina Earthquake

On 28 December 1908, a powerful earthquake and tsunami struck Sicily and Calabria. The cities of Messina and Reggio Calabria were almost completely destroyed. Between 75,000 and 200,000 people lost their lives.

News of the disaster reached Prime Minister Giolitti slowly because communication lines were destroyed. The Italian navy and army quickly responded, helping the injured, providing food, and evacuating survivors. Giolitti declared martial law, meaning looters would be shot. King Victor Emmanuel III and Queen Elena arrived to help. The disaster led to international relief efforts.

1909 Election and Resignation

In the 1909 Italian general election, Giolitti's party won a majority. However, he faced challenges over new laws. He resigned on 2 December 1909. Giolitti suggested Sidney Sonnino as the new Prime Minister. After a few months, Giolitti supported Luigi Luzzatti as the new head of government. Even when not officially Prime Minister, Giolitti remained a powerful figure.

After Being Prime Minister

Voting Rights for Men

During Luzzatti's government, there was a big debate about expanding voting rights. Socialists and other groups wanted to introduce universal manhood suffrage, meaning all adult men could vote. Luzzatti proposed a more limited expansion.

Giolitti, however, publicly supported universal male suffrage. He wanted to become Prime Minister again and work with the Socialists. He also believed that giving more men the right to vote would bring more conservative voters to the polls and gain support from grateful socialists. This reform greatly increased the number of voters from 3 million to 8.5 million.

Many historians believe this change helped "mass parties" like the Socialists and later the Fascists, rather than Giolitti's own liberal party. Giolitti believed Italy could not grow without more people participating in public life.

Some politicians suggested giving women the right to vote too, but Giolitti opposed it, saying it was too risky for the time.

Fourth Time as Prime Minister

Luzzatti resigned on 30 March 1911, and King Victor Emmanuel III once again asked Giolitti to form a new government.

Social Policies and Reforms

In his fourth term, Giolitti continued to seek an alliance with the Italian Socialist Party. He introduced universal suffrage for men and brought in left-wing social policies. He created the National Insurance Institute, which took over insurance from private companies. He also appointed the socialist Alberto Beneduce to lead this institute.

New laws were passed in 1912 to provide benefits for pregnant women and mothers. In 1912, Giolitti's government also approved a law that paid a monthly allowance to members of Parliament. Before this, parliamentarians did not receive a salary, which favored wealthy candidates.

The Libyan War

Italy had long wanted to control Libya, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire. In 1902, Italy and France secretly agreed that Italy could intervene in Libya.

In early 1911, Italian newspapers began a strong campaign for an invasion of Libya. They described it as rich in resources and easy to conquer. The Italian government was hesitant at first, but preparations for an invasion began in the summer. Giolitti checked with other European powers about their reactions. The Italian Socialist Party was divided and ineffective in opposing the war.

On 26 September 1911, Italy sent an ultimatum to the Ottoman government. The Ottomans offered to transfer control of Libya without war, but Giolitti refused. War was declared on September 29, 1911. Giolitti was criticized for declaring war without consulting Parliament.

On 18 October 1912, Turkey officially surrendered. Italy gained control of the Ottoman province of Tripolitania, which became Italian Libya. During the conflict, Italian forces also occupied the Dodecanese islands. Although Italy agreed to return them, it kept control until 1923.

This war was costly for Italy, much more than Giolitti had estimated. It also sparked nationalism in the Balkan states, leading to the First Balkan War soon after.

Forming the Liberal Union

In 1913, Giolitti created the Liberal Union. This was a political alliance that brought together different liberal groups into a single, centrist coalition. This group largely dominated the Italian Parliament.

Giolitti was a master of trasformismo, a political method where he created flexible governments that avoided extreme political ideas from both the left and the right.

The Gentiloni Pact

In 1904, Pope Pius X allowed Catholics to vote for government candidates, especially where the Italian Socialist Party might win. The Church saw Socialists as a major enemy.

When the Pope lifted the ban on Catholic involvement in politics in 1913, Giolitti worked with the Italian Catholic Electoral Union. This led to the Gentiloni pact. Under this agreement, Catholic voters supported Giolitti's candidates. In return, Giolitti's supporters agreed to favor the Church's views on issues like funding Catholic schools and blocking divorce laws.

The Vatican wanted to stop the rise of Socialism and guide Catholic organizations. Giolitti saw this as a chance for Catholics and the liberal government to work together.

1913 Election and Resignation

A general election was held in October 1913. Giolitti's Liberal Union kept a small majority in Parliament. However, the election showed the beginning of a decline for the traditional Liberal establishment.

In March 1914, Giolitti's government coalition fell apart, and he resigned on March 21.

World War I

After Giolitti resigned, Antonio Salandra became Prime Minister. Giolitti and Salandra disagreed about Italy joining World War I. Giolitti believed Italy was not ready for war and wanted to stay neutral. He tried to use his influence in Parliament to stop Salandra, but public opinion pushed for war.

When the war started in August 1914, Salandra declared Italy neutral. However, Salandra and his foreign ministers secretly explored which side would offer Italy the best rewards for joining the war. On 26 April 1915, Italy signed the secret Treaty of London with the Triple Entente (United Kingdom, France, and Russia). Italy agreed to leave its alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary and declare war on them within a month, in exchange for land after the war. Giolitti initially did not know about this treaty.

While Giolitti supported neutrality, Salandra and his foreign minister, Sidney Sonnino, pushed for Italy to join the Allies. Despite most of Parliament opposing war, Italy entered the conflict. On 3 May 1915, Italy officially left the Triple Alliance. Giolitti and many others in Parliament opposed declaring war, but nationalist crowds demonstrated for war. On 13 May 1915, Salandra offered to resign, but Giolitti refused to take his place, fearing public unrest. On 23 May 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary.

Giolitti then retired from politics and stayed out of public life during the war. This made him lose influence, and some people saw him as a traitor.

Fifth Time as Prime Minister

Giolitti returned to politics after World War I ended. In the 1919 election, he argued that a small group had dragged Italy into war against the will of the majority. This put him at odds with the growing movement of Fascists. This election was the first to use a new system called proportional representation.

The Red Biennium

The election happened during the Biennio Rosso ("Red Biennium"), a two-year period (1919-1920) of major social unrest in Italy after the war. There was high unemployment and political instability. This period saw many strikes, worker protests, and occupations of factories and land. In cities like Turin and Milan, workers took over factories. This unrest also spread to farming areas.

In the election, Giolitti's Liberal coalition lost its majority in Parliament. This was due to the success of the Italian Socialist Party and the Italian People's Party.

Giolitti became Prime Minister again on 15 June 1920, because he was seen as the only person who could handle the difficult situation. He refused to use force against striking workers and factory occupations. He believed that using force would only make things worse.

The Fiume Exploit

After World War I, the city of Fiume (now Rijeka in Croatia) was not given to Italy, even though Italy had been promised some land. Italian nationalist and poet Gabriele D'Annunzio was very angry about this. On September 12, 1919, he led about 2,600 soldiers and nationalists to take over the city. He announced that he had annexed Fiume to Italy.

Giolitti's government opposed this action. D'Annunzio refused to give up. Italy then blocked Fiume and demanded that D'Annunzio's forces surrender. On 12 November 1920, Italy and Yugoslavia signed the Treaty of Rapallo, making Fiume an independent state. D'Annunzio ignored the treaty and declared war on Italy. On 24 December 1920, Giolitti sent the Italian army and navy to bomb the city, forcing D'Annunzio's men to leave. Fiume became part of Italy in 1924.

1921 Election and Resignation

As fears of a communist takeover grew, the political leaders began to tolerate the rise of the Fascists led by Benito Mussolini. Giolitti did not try to stop the Fascists' violent takeovers of local governments or their attacks on political opponents.

In 1921, Giolitti formed the National Blocs, an election group that included his Liberals, Mussolini's Fascists, and other right-wing groups. Giolitti hoped to stop the growth of the Italian Socialist Party.

Giolitti called for new elections in May 1921. However, his group only won 19.1% of the votes. This disappointing result forced him to resign.

The Rise of Fascism

Still a leader of the Liberals, Giolitti did not strongly resist Italy's move towards Italian Fascism. In 1921, he supported the government of Ivanoe Bonomi. When Bonomi resigned, Liberals again suggested Giolitti as Prime Minister, believing he could save the country from civil war. However, the People's Party opposed him. On 26 February 1922, King Victor Emmanuel III asked Luigi Facta, a Liberal and friend of Giolitti, to form a new government.

When Fascist leader Benito Mussolini organized the March on Rome in October 1922, Giolitti was away. Prime Minister Facta ordered a state of siege for Rome to stop the Fascists, but King Victor Emmanuel III refused to sign the order. On 28 October, the King gave power to Mussolini, who had the support of the military and business leaders.

Giolitti initially supported Mussolini's government, hoping the Fascists would become more moderate. He even voted for the controversial Acerbo Law, which gave the largest party a large number of seats in Parliament. However, Giolitti withdrew his support in 1924, voting against a law that limited press freedom. He told Mussolini in Parliament: "For love of our fatherland, do not treat the Italian people as if it did not deserve the freedom that it always had in the past."

In December 1925, the local council in Cuneo, where Giolitti was president, asked him to join the National Fascist Party. Giolitti, who now fully opposed the Fascist government, resigned from his position. In 1928, he spoke against a law that effectively ended free elections.

Death and Lasting Impact

Giovanni Giolitti remained in Parliament until his death in Cavour, Piedmont, on 17 July 1928. His last words were about his long service and his inability to sing Giovinezza, the Fascist anthem.

Historians see Giolitti as one of Italy's most important Prime Ministers after Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. He was a practical politician who believed in progress through economic growth. He thought that most opponents could be convinced to become allies.

Giolitti aimed to govern from the political middle ground, shifting between conservative and progressive ideas to keep stability. Some critics from the right called him a "socialist" because he worked with socialist groups. Some from the left accused him of unfair election practices, saying he won elections with the support of criminals.

Giolitti is considered a key liberal reformer in Europe during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He introduced nearly universal male suffrage and allowed labour strikes. He tried to work with new political groups, including socialists and Catholics. Later in his life, he even tried, but failed, to work with Italian Fascism.

Antonio Giolitti, a politician after World War II, was his grandson.

The Giolittian Era

Giolitti's approach of not interfering in strikes, even violent ones, was initially successful. However, it also led to some disorder. When Prime Minister Zanardelli resigned, Giolitti became Prime Minister in November 1903. His important role from the early 1900s until 1914 is known as the Giolittian Era. During this time, Italy saw its industries grow, organized labor movements rise, and a new Catholic political movement emerge.

Italy's economy expanded due to stable money, moderate protectionism (protecting local industries), and government support for production. Foreign trade doubled between 1900 and 1910, wages increased, and the general standard of living improved. However, there were also social problems. Strikes became more frequent and lasted longer, with major strikes in 1904, 1906, and 1908.

Many Italians moved abroad between 1900 and 1914, and rapid industrialization in the North increased the economic gap with the South. Giolitti was skilled at gaining parliamentary support from various groups, including socialists and Catholics, who had previously been excluded from government. Although he was anti-clerical (against the Church's political power), he gained Catholic support by delaying a divorce bill and appointing some Catholics to important positions.

Giolitti was one of Italy's longest-serving Prime Ministers because he mastered trasformismo. This meant he was very good at influencing and gaining support from officials. Critics accused Giolitti of manipulating elections, especially in areas where he had strong support. However, he refined these practices in the 1904 and 1909 elections, which gave the Liberals strong majorities.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Giovanni Giolitti para niños

In Spanish: Giovanni Giolitti para niños

- Liberalism and radicalism in Italy

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |