Francesco Crispi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francesco Crispi

OSSA, OSML, OCI, OMS

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Prime Minister of Italy | |

| In office 15 December 1893 – 10 March 1896 |

|

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Giovanni Giolitti |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Starabba |

| In office 29 July 1887 – 6 February 1891 |

|

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Agostino Depretis |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Starabba |

| President of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 26 November 1876 – 26 December 1877 |

|

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Branchieri |

| Succeeded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 15 December 1893 – 9 March 1896 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Giovanni Giolitti |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Starabba |

| In office 4 April 1887 – 6 February 1891 |

|

| Prime Minister | Agostino Depretis Himself |

| Preceded by | Agostino Depretis |

| Succeeded by | Giovanni Nicotera |

| In office 26 December 1877 – 7 March 1878 |

|

| Prime Minister | Agostino Depretis |

| Preceded by | Giovanni Nicotera |

| Succeeded by | Agostino Depretis |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 29 July 1887 – 6 February 1891 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Agostino Depretis |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Starabba |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 18 February 1861 – 2 March 1897 |

|

| Constituency | Castelvetrano (1861–1870) Tricarico (1870–1880) Palermo (1880–1897) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 October 1818 Ribera, Kingdom of the Two Sicilies |

| Died | 11 August 1901 (aged 82) Naples, Kingdom of Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Political party | Historical Left (1848–1883; 1886–1901) Dissident Left (1883–1886) |

| Spouses |

Rosina D'Angelo

(m. 1837; died 1839)Rosalia Montmasson

(m. 1854; div. 1878)Lina Barbagallo

(m. 1878) |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | University of Palermo |

| Profession | |

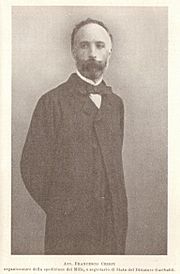

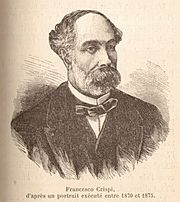

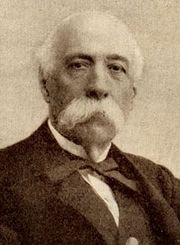

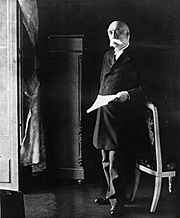

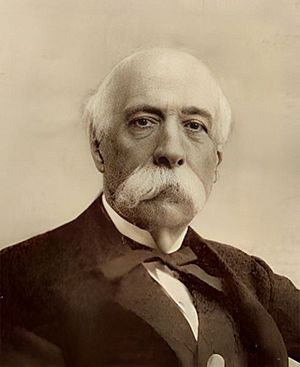

Francesco Crispi (born October 4, 1818 – died August 11, 1901) was an important Italian leader and patriot. He played a big part in the Risorgimento, which was the movement to unite Italy. He was a close friend of Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, who were also key figures in Italian unification. Crispi helped bring Italy together in 1860.

He served as Prime Minister of Italy for six years, first from 1887 to 1891, and then again from 1893 to 1896. He was the first Prime Minister to come from Southern Italy. Crispi was well-known around the world and was often mentioned alongside other famous leaders like Otto von Bismarck and William Ewart Gladstone.

Crispi started his career as a supporter of democracy and Italian unity. However, he later became a strong and powerful Prime Minister. He was known for being tough and sometimes caused problems with France. His career ended after a major banking scandal and a big military loss in 1896 at the Battle of Adwa, which stopped Italy's plans to colonize Ethiopia. Because of his strong leadership style, some people see Crispi as a leader who paved the way for later figures like Benito Mussolini.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Francesco Crispi came from a middle-class family in Sicily. His parents, Tommaso Crispi and Guiseppa Genova Crispi, were both from Sicily. His family had Greek and Albanian roots. Crispi was even baptized in the Greek Orthodox Church. He learned Italian as well as Greek, Albanian, and Sicilian. His uncle, Giuseppe Crispi, wrote an important book about the Albanian language. Francesco Crispi was very interested in Greece and hoped to visit it one day. He even worked to bring Greece and Albania closer together.

When he was five, Crispi was sent to live with a family in Villafranca to get an education. In 1829, at age 11, he went to a seminary in Palermo where he studied classic subjects. His uncle, Giuseppe Crispi, was the head of this school. Francesco stayed there until 1834 or 1835.

Around this time, Crispi became good friends with a poet and doctor named Vincenzo Navarro. This friendship introduced him to the Romantic movement. In 1835, he studied law at the University of Palermo and became a lawyer in 1837. Between 1838 and 1839, Crispi started his own newspaper called L'Oreteo. Through this, he met many political figures. In 1842, he wrote about the importance of educating poor people and the need for everyone, including women, to be equal under the law. In 1845, Crispi became a judge in Naples, where he was known for his liberal and revolutionary ideas.

The 1848 Sicilian Uprising

On December 20, 1847, Crispi went to Palermo to help plan a revolution against the Bourbon monarchy and King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies. The revolution began on January 12, 1848, making it the first of many revolutions that year. It was carefully planned by Crispi and others to start on King Ferdinand II's birthday.

The Sicilian nobles quickly brought back their old constitution from 1812. This constitution supported democracy and a strong Parliament. There was also an idea to create a group of all the states in Italy. Crispi was chosen to be a member of the temporary Sicilian Parliament. He was in charge of the Defence Committee and supported the idea of Sicily becoming separate from Naples.

Sicily was a nearly independent state for 16 months. However, the Bourbon army took back control of the island by force on May 15, 1849. Crispi was not given forgiveness and had to leave the country.

Life in Exile

After leaving Sicily, Crispi found safety in Marseille, France. There, he met Rose Montmasson, who would become his second wife. In 1849, he moved to Turin, the capital of the Kingdom of Sardinia, where he worked as a journalist. During this time, he became friends with Giuseppe Mazzini, a republican leader. In 1853, Crispi was linked to a plot by Mazzini and was arrested. He was sent to Malta, where he married Rose Montmasson on December 27, 1854.

Then, he moved to London and continued his close friendship with Mazzini. He became involved in the politics of the national movement, giving up his earlier idea of Sicilian separatism. On January 10, 1856, he moved to Paris and kept working as a journalist.

In Sicily with Garibaldi

The Expedition of the Thousand

In June 1859, Crispi returned to Italy. He said he was a republican and wanted Italy to be united. He traveled around Italy in secret, using different disguises and fake passports. He visited Sicilian cities twice that year, getting ready for the uprising in 1860.

Crispi helped convince Giuseppe Garibaldi to sail with his Expedition of the Thousand. This group of volunteers landed in Sicily on May 11, 1860. Their goal was to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which was ruled by the Bourbons. This was a very brave and risky plan, as they aimed to conquer a kingdom with a much larger army and navy with only a thousand men.

The expedition was a great success! It ended with a vote that brought Naples and Sicily into the Kingdom of Sardinia. This was the last step before the creation of the Kingdom of Italy on March 17, 1861. Crispi used his political influence to help unite Italy. Different groups joined the expedition for different reasons: Garibaldi wanted a united Italy, Sicilian business owners wanted an independent Sicily as part of Italy, and farmers wanted land and an end to unfair treatment.

Garibaldi's Government in Sicily

After Palermo fell, Crispi was made the First Secretary of State in the temporary government. Soon, a disagreement started between Garibaldi's government and the people sent by Cavour. They argued about when Sicily should officially join Italy. Garibaldi's government created a Sicilian Army and navy.

Cavour was worried about how quickly Garibaldi was winning. In early July, he suggested that Sicily should join Piedmont right away. But Garibaldi strongly refused, saying it should wait until the war was over. Crispi also strongly opposed this idea.

In Naples, Garibaldi's temporary government was mostly controlled by Cavour. Crispi tried to gain more power and influence there. However, the revolutionary spirit was fading. On October 3, 1860, Garibaldi appointed Giorgio Pallavicino as the temporary leader of Naples. Pallavicino was a supporter of the House of Savoy (the royal family). He immediately said that Crispi was not suitable for the job of Secretary of State.

Cavour insisted that Southern Italy must join the Kingdom of Sardinia without any conditions, through a vote. Crispi wanted to continue the revolution to free Rome and Venice. He suggested electing a parliamentary assembly instead of a simple vote. But the temporary leaders of Sicily and Naples both chose the vote. On October 13, Crispi resigned from Garibaldi's government.

Member of Parliament

The general election of 1861 happened on January 27, even before the Kingdom of Italy was officially created on March 17. Francesco Crispi was elected as a member of the Historical Left party. He kept his seat in Parliament for the rest of his life.

Crispi became known as the most outspoken member of his group. He criticized the Historical Right party for being too diplomatic. He was very ambitious and sometimes hard to work with, earning him the nickname Il Solitario (The Loner). In 1864, he decided to support the monarchy instead of Mazzini's republican ideas. He wrote to Mazzini, "The monarchy unites us; the republic would divide us."

In 1867, he worked to stop Garibaldi's invasion of the papal states, predicting that France would then occupy Rome. When the Franco-German War started, he worked hard to prevent Italy from allying with France. He also pushed the government to take Rome. After a leader named Urbano Rattazzi died in 1873, Crispi's friends wanted him to lead the Left party. But Crispi, wanting to reassure the king, helped Agostino Depretis get elected instead.

President of the Chamber of Deputies

After the general election in 1876, where the Left party won a lot of votes, Crispi was elected President of the Chamber of Deputies. This meant he was in charge of the main part of the Italian Parliament.

In the autumn of 1877, Crispi traveled to London, Paris, and Berlin for secret meetings. He built good relationships with British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone and German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Bismarck even offered Italy Albania as a possible reward if Austria-Hungary took over Bosnia. However, Crispi refused, preferring Italian regions that were under Austro-Hungarian rule.

Minister of the Interior

In December 1877, Crispi became the Italian Minister of the Interior in Depretis's government. Even though he was only in office for 70 days, his time was important for making Italy a united monarchy. During this period, Crispi tried to bring together the many different groups within the Left party.

On January 9, 1878, King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy died, and King Umberto I of Italy took the throne. Crispi helped make sure the new king was called Umberto I of Italy, rather than Umberto IV of Savoy. This showed that Italy was now one united country.

On February 7, 1878, Pope Pius IX died, and a new pope needed to be chosen. Crispi helped convince the cardinals to hold the election in Rome. This helped show that Rome was the rightful capital of Italy.

First Term as Prime Minister

On July 29, 1887, Francesco Crispi became the new Prime Minister of Italy. He was the first Prime Minister from Southern Italy. Crispi quickly became known as a leader who wanted to make many changes. However, his strong leadership style caused many protests from his opponents, who said he was too powerful.

Crispi worked on important reforms. He ended the death penalty, removed laws against strikes, and limited the power of the police. He also reformed the laws about crime and justice with the help of his Minister of Justice, Giuseppe Zanardelli. He improved public health laws and created rules to protect Italians working abroad. He wanted to make the government stronger and expand Italy's influence in the world.

Changes at Home

One of Crispi's most important actions was to change how the government was organized. He made the Prime Minister's role stronger. This reform aimed to separate the government's work from Parliament's political games. It allowed the government to decide how many ministries there would be and what they would do. This reform was approved in December 1887.

In 1889, Crispi's government also created a new set of criminal laws. These laws made Italy's criminal justice system the same across the country, ended the death penalty, and allowed people to strike. This new code was seen as a great achievement by legal experts in Europe.

Another important change was to local government. This reform allowed more people to vote in local elections. The most debated part of the law was that mayors, who used to be chosen by the government, would now be elected by the people in larger towns and cities. This law was approved in December 1888.

On December 22, 1888, Crispi also created the first Italian law for a national healthcare system. This was important after several cholera outbreaks had caused many deaths. Crispi was also the first politician to make the Italian government play a role in charity and helping others. Before this, these activities were mostly done by private groups, especially the Catholic Church, which strongly opposed his changes.

Foreign Policy

As Prime Minister, Crispi followed a strong foreign policy to make Italy more powerful. He saw France as a constant rival and hoped for support from Britain. However, Britain was friendly with France and did not help, which disappointed Crispi. He then turned to expanding Italy's power in Africa, especially against Ethiopia and the Ottoman province of Tripolitania (now Libya).

Working with Germany

One of Crispi's first actions as Prime Minister was to visit the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. He wanted to discuss how the Triple Alliance (an agreement between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy) was working.

Crispi based his foreign policy on this alliance. He took a strong stance against France, ending trade talks and refusing France's invitation for Italy to participate in the Paris Exhibition of 1889. The Triple Alliance meant Italy might have to go to war with France, which required Italy to spend a lot more money on its military. This made the alliance unpopular in Italy. Crispi also started a trade war with France in 1888, which was very bad for Italy's economy. This trade war ended in 1898.

Colonial Ambitions

Francesco Crispi was an Italian nationalist who wanted Italy to become a colonial power. This led to conflicts with France, which did not agree with Italy's claims to Tunisia and opposed Italy's expansion in Africa.

Under Crispi's leadership, Italy signed the Treaty of Wuchale with King Menelik II of Shewa (who later became Emperor of Ethiopia) in 1889. This treaty stated that certain regions were part of the Italian colony of Eritrea. Italy also promised financial help and military supplies to Ethiopia.

Albanian Question

Italy was also interested in the Balkans and the Adriatic Sea. Crispi believed that an independent Albania would protect Italy's interests. He thought that a union between Greece and Albania would be best for Albania. He even started a committee in Rome to work towards this goal. Crispi encouraged cultural ties between Italians of Albanian descent and Albanians in the Balkans. To counter Austria-Hungary's influence, Crispi opened the first Italian schools in Shkodër, Albania, in 1888.

Resignation

The general election in 1890 was a big win for Crispi. Most of the deputies supported his government. However, problems started in October. Emperor Menelik of Ethiopia argued that the Italian version of the Wuchale Treaty did not say Ethiopia had to be an Italian protectorate. This caused a scandal. A few days later, the Finance Minister, Giovanni Giolitti, left the government.

The final blow came when the new Finance Minister, Bernardino Grimaldi, showed that the government's planned spending was much higher than expected. After this, Crispi's government lost its support in Parliament. Prime Minister Crispi resigned on February 6, 1891.

After His First Term

After Crispi's government fell, King Umberto I asked Antonio Starabba di Rudinì to form a new government. This government faced many problems. In May 1892, Giolitti, who had become the new leader of the Left party, decided not to support it anymore.

After that, King Umberto I appointed Giolitti as the new Prime Minister. However, Giolitti's government had little support. In December 1892, the Prime Minister was involved in a major financial scandal.

Return to Power and Second Term

In December 1893, Giolitti's government was unable to control public unrest, especially in Sicily. This led to many people wanting Crispi to return to power.

The Fasci Siciliani Movement

The Fasci Siciliani was a popular movement of democratic and socialist ideas that grew in Sicily between 1889 and 1894. This movement gained support from the poorest people on the island. They wanted new rights and better conditions for farmers and miners. The movement grew very strong in the summer of 1893, leading to widespread strikes when their demands were not met.

The leaders of the movement could not keep the situation under control. Landowners asked the government to step in. Giovanni Giolitti tried to stop the protests, but his actions were not very strong. On November 24, Giolitti resigned as Prime Minister. In the weeks before Crispi formed a government on December 15, 1893, the violence spread quickly.

On January 3, 1894, Crispi declared a state of emergency across Sicily. He sent 40,000 troops to the island. The old order was restored, and many people were arrested. The government arrested not only the leaders but also many poor farmers, students, and anyone suspected of supporting the movement. Many were jailed for small reasons, like shouting "down with the King." In April and May 1894, trials were held against the leaders of the Fasci, which effectively ended the movement.

Financial Issues and an Attack

Crispi strongly supported his Finance Minister, Sidney Sonnino, who worked hard to fix Italy's financial problems after a crisis in 1892–1893. Sonnino's ideas were criticized, and he resigned on June 4, 1894. Crispi resigned the next day, but the King asked him to form a new government again.

On June 16, 1894, an anarchist named Paolo Lega tried to shoot Crispi, but he missed. A few days later, an Italian anarchist killed the French President. Because of this increased fear of anarchists, Crispi introduced new laws in July 1894 that were also used against socialists. These laws gave police more power to arrest and deport people.

Parliament showed support for Crispi, which made his position stronger. This helped approve Sonnino's financial reforms, which helped Italy recover economically.

Accusations and Re-election

In 1894, Crispi was almost removed from the Masonic group Grande Oriente d'Italia because he seemed too friendly with the Catholic Church. He had previously been against the Church but had changed his mind.

At the end of 1894, his rival Giovanni Giolitti tried to hurt Crispi's reputation by showing Parliament some old documents. These papers showed that Crispi and his wife had taken loans from a bank involved in a scandal.

Crispi's tough actions against unrest and his refusal to give up the Triple Alliance or the colony in Eritrea caused a disagreement with the radical leader Felice Cavallotti. Cavallotti started a campaign to spread bad information about Crispi. He suggested that a committee should investigate Crispi's connections to the bank scandal.

On December 15, the committee released its report, causing some arguments in Parliament. Crispi, wanting to protect the government, asked the King to dissolve Parliament. On January 13, 1895, King Umberto I dissolved Parliament. Giolitti, who was facing trial for the bank scandal, had to move to Berlin because his protection as a Member of Parliament ended.

Giolitti and Cavallotti's attacks continued, but they had little effect. The general election of 1895 gave Crispi a large majority of 334 seats out of 508. On June 25, 1895, Crispi refused a request for a parliamentary investigation into his role in the bank scandal. He said that as Prime Minister, he felt "invulnerable" because he had "served Italy for 53 years." Even with his majority, Crispi preferred to rule by royal decree instead of passing laws through Parliament, which raised concerns about him being too authoritarian.

War in Ethiopia and Resignation

During his second term, Crispi continued Italy's plan to expand its colonies in East Africa. King Umberto I even joked that "Crispi wants to occupy everywhere, even China and Japan." The King strongly supported Crispi, saying that Crispi was "a pig, but a necessary pig" who had to stay in power for "the national interest." Crispi took a very aggressive approach to foreign policy. He talked about attacking France, wanted to send a navy to seize Albania, and planned to send forces to China and South Africa.

The main event during his time as Prime Minister was the First Italo-Ethiopian War. This war started because of a disagreement over a treaty that Italians claimed made Ethiopia an Italian protectorate. To their surprise, the Ethiopian ruler Menelik II was supported by his traditional enemies. So, the Italian army, which invaded Ethiopia from Eritrea in 1893, faced a more united force than they expected. Also, Ethiopia received help from Russia, which sent military advisors and sold weapons. France also supported Ethiopia to prevent Italy from becoming a colonial rival.

Full-scale war broke out in 1895. Italian troops had some early success, but Ethiopian forces fought back and surrounded the Italian fort of Meqele, forcing it to surrender. In April 1895, Crispi pulled some Italian troops out of Ethiopia to save money. He told General Baratieri to just tax the Ethiopians more to get money for the war. Crispi did not understand that Ethiopia was a poor country and could not provide enough money to support a modern army.

On February 22, 1896, King Umberto removed General Baratieri as commander of the Italian forces. On February 25, Crispi sent a telegram to Baratieri, criticizing him for avoiding big battles. He demanded that Baratieri take decisive action "whatever the cost to save the honour of the army." In response, Baratieri decided to attack a much larger Ethiopian force on March 1, 1896, near Adwa.

In the Battle of Adwa, the Ethiopian army decisively defeated the outnumbered Italians and forced them to retreat back into Eritrea. This battle caused more Italian deaths than any other major European battle in the 19th century. More Italians died in one day at Adwa than in all the wars to unite Italy.

After Adwa, Crispi announced that he planned to continue the war against Ethiopia and send more troops. This caused a public outcry against the unpopular war. Riots broke out in several Italian cities. Within two weeks, Crispi's government collapsed because Italians were tired of "foreign adventures." In Rome, people protested, shouting "death to the king!" and "long live the republic!" The war had badly damaged the King's reputation, as he had strongly supported Crispi. Crispi was against making peace with Ethiopia, calling it humiliating to make peace with "barbarians." He also said he didn't care about the lives of the nearly 3,000 Italians taken prisoner by the Ethiopians, saying they were "expendable."

Downfall and Death

The new government, led by Antonio Starabba, Marchese di Rudinì, supported Cavallotti's campaign against Crispi. In late 1897, legal authorities asked Parliament for permission to prosecute Crispi for misusing money. A parliamentary investigation found that Crispi, when he became Prime Minister in 1893, found the secret service funds empty. He had borrowed money from a state bank to fund it, repaying it later with regular payments from the treasury. The committee found this action improper and Parliament voted to criticize him, but they did not allow him to be prosecuted.

Crispi resigned his seat in Parliament, but his voters in Palermo re-elected him by a large majority in April 1898. For some time, he did not participate much in politics, mainly because he was losing his eyesight. A successful eye surgery in June 1900 restored his vision. Despite being 81 years old, he started to get involved in politics again.

However, his health soon began to fail. He died in Naples on August 11, 1901. Many witnesses said his last words were: "Before closing my eyes to life, I would have the supreme comfort of knowing that our homeland is beloved and defended by all its sons."

Legacy

Crispi was a very colorful and patriotic person. He had a lot of energy but also a strong temper. His life was often dramatic and full of disagreements. Some people believed his strong pride and quick temper came from his Albanian heritage. He started as a revolutionary and a supporter of democracy, but as Prime Minister, he became very powerful and did not like Italian liberals. He was born a rebel and died as someone who put down rebellions.

At the end of the 19th century, Crispi was the most important figure in Italian politics for ten years. The famous composer Giuseppe Verdi called him 'the great patriot'. He was seen as a more careful leader than Cavour, a more realistic planner than Mazzini, and a smarter figure than Garibaldi. When he died, European newspapers wrote longer obituaries for him than for any Italian politician since Cavour.

As Prime Minister in the 1880s and 1890s, Crispi was famous worldwide and often mentioned alongside leaders like Bismarck, Gladstone, and Salisbury. He started as an enlightened Italian patriot and democratic liberal, but he became a warlike and powerful Prime Minister who admired Bismarck. He is often seen as a person who influenced Benito Mussolini. Mussolini praised Crispi as the creator of "Italian imperialism" and said Crispi's foreign policy inspired Fascist foreign policy. Mussolini presented his own foreign policies, like conquering Ethiopia to "avenge Adwa" and allying with Nazi Germany, as a continuation of Crispi's policies. After 1945, many streets named after Crispi were renamed because of his connection to Fascism.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Francesco Crispi para niños

In Spanish: Francesco Crispi para niños