Giuseppe Mazzini facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Giuseppe Mazzini

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Triumvir of the Roman Republic | |

| In office 5 February – 3 July 1849 Serving with Aurelio Saffi, Carlo Armellini

|

|

| Preceded by | Aurelio Saliceti |

| Succeeded by | Aurelio Saliceti |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 June 1805 Genoa, Gênes, France |

| Died | 10 March 1872 (aged 66) Pisa, Tuscany, Italy |

| Political party | Young Italy (1831–1848) Italian National Association (1848–1853) Action Party (1853–1867) |

| Alma mater | University of Genoa |

| Profession |

|

|

Philosophy career |

|

| Era | Modern philosophy

|

| Region | Western philosophy

|

| School | Italian nationalism Romanticism |

|

Main interests

|

History, theology, politics |

|

Notable ideas

|

Pan-Europeanism, irredentism (Italian), popular democracy, class collaboration |

|

Influences

|

|

| Signature | |

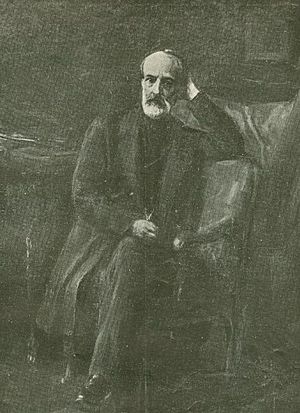

Giuseppe Mazzini (22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an important Italian politician, writer, and activist. He worked tirelessly for the unification of Italy, a movement known as the Risorgimento. His efforts helped create a single, independent Italy. Before this, Italy was made up of many separate states, often controlled by foreign powers.

Mazzini was an Italian nationalist who believed in a republican government. This means he wanted Italy to be a country ruled by its people, not a king. His ideas greatly influenced republican movements in Italy and across Europe. Many later leaders, like American president Woodrow Wilson and post-colonial figures such as Mahatma Gandhi, were inspired by him.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Giuseppe Mazzini was born in Genoa, which was then part of the Ligurian Republic. His father, Giacomo Mazzini, was a university professor. His mother, Maria Drago, was known for her beauty and strong religious beliefs.

From a young age, Mazzini showed a great ability to learn. He was also very interested in politics and literature. He started university at 14 and became a lawyer in 1826. He often helped poor people with legal problems. He also hoped to become a writer.

In 1827, Mazzini joined a secret political group called the Carbonari. This group aimed to bring about political change. He was arrested in Genoa later that year and kept in prison. In 1831, he was released but had to stay in a small village. Instead, he chose to go into exile, moving to Geneva, Switzerland.

Founding Young Italy

In 1831, Mazzini moved to Marseille, France. There, he became a popular leader among Italians who were also in exile. He founded a new secret political group called Young Italy. Its goal was to unite Italy into "One, free, independent, republican nation."

Mazzini believed that a popular uprising would create a unified Italy. He thought this would also inspire revolutions across Europe. The group's motto was "God and the People." They believed that uniting the many states and kingdoms of Italy into a single republic was the only way to achieve true Italian freedom.

Early Attempts at Uprising

Mazzini's political work gained followers in many parts of Italy. By 1833, Young Italy had about 60,000 members. In that year, Mazzini planned his first uprising. It was supposed to start in several cities.

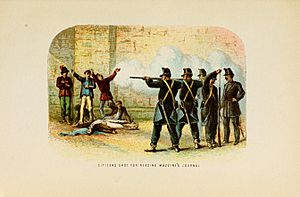

However, the government discovered the plan before it could begin. Many revolutionaries were arrested, and 12 were executed. Mazzini was tried while absent and sentenced to death.

Despite this setback, Mazzini organized another uprising for the next year. Italian exiles were to enter Italy from Switzerland. Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had just joined Young Italy, was to lead a similar effort from Genoa. But, government troops easily stopped this new attempt.

Because of these events, Mazzini was arrested in Switzerland in 1834. He was then sent away from the country. He moved to Paris, where he was again imprisoned. He was released only after promising to move to England. In January 1837, Mazzini and some friends moved to London. They lived in difficult financial conditions.

Life in London Exile

In 1840, Mazzini restarted the Giovine Italia (Young Italy) group in London. He also began publishing a newspaper called Apostolato popolare ("Apostleship of the People").

Several more attempts to start uprisings in Italy failed. This discouraged Mazzini for a while. He was also left by a close friend, Giuditta Sidoli, who returned to Italy. His mother's support encouraged Mazzini to create new groups. These groups aimed to unite or free other nations, similar to Young Italy. Examples included "Young Germany," "Young Poland," and "Young Switzerland." These were all part of a larger group called "Young Europe."

Mazzini also started an Italian school for poor children in London in 1841. From London, he wrote many letters to his contacts across Europe and South America. He also became friends with the writer Thomas Carlyle. The "Young Europe" movement even inspired a group of young Turkish army cadets who later became known as the "Young Turks."

In 1843, Mazzini organized another revolt in Bologna. This caught the attention of two Austrian Navy officers, Attilio and Emilio Bandiera. With Mazzini's help, they landed in southern Italy. However, they were arrested and executed. Mazzini accused the British government of sharing information about their plans. This led to a debate in the British Parliament. When it was confirmed that his private letters had been opened and shared, Mazzini gained more support from British liberals. They were upset by this government intrusion.

The Revolts of 1848–1849

In April 1848, Mazzini arrived in Milan. The people there had rebelled against the Austrian soldiers. The First Italian War of Independence began, started by King Charles Albert of Piedmont. However, this war failed completely. Mazzini was not popular in Milan because he wanted Lombardy to be a republic, not part of Piedmont. He left Milan and joined Garibaldi's forces, moving with him to Switzerland.

On 9 February 1849, a republic was declared in Rome. The Pope had already been forced to leave. Mazzini arrived in Rome on the same day. He was appointed as one of three leaders, called a triumvir, of the new republic on 29 March. He quickly became the real leader of the government. He showed good skills in making social reforms.

However, French troops, called by the Pope, arrived. It became clear that the Republican troops, led by Garibaldi, could not win. On 12 July 1849, Mazzini left Rome and moved back to Switzerland.

Later Activities and Death

Mazzini spent 1850 hiding from the Swiss police. In July, he founded the "Friends of Italy" association in London. This group aimed to gain support for Italian freedom. Two failed revolts in 1852 and 1853 greatly weakened Mazzini's organization. He also opposed an alliance between Piedmont and Austria for the Crimean War.

In 1856, he returned to Genoa to plan more uprisings. The only major attempt was led by Carlo Pisacane in Calabria, which also failed. Mazzini managed to escape the police but was sentenced to death in his absence. From this time on, Mazzini played a smaller role in the Italian unification. The main leaders became King Victor Emmanuel II and his prime minister, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour.

In 1858, he started another journal in London called Pensiero e azione (Thought and Action). In 1859, he signed a statement against an alliance between Piedmont and France. This alliance led to the Second War of Italian Independence. In 1860, he published Doveri dell'uomo ("Duties of Man"). This book summarized his ideas about morals, politics, and society.

The new Kingdom of Italy was created in 1861 under the Savoy monarchy. In 1862, Mazzini joined Garibaldi in another failed attempt to free Rome. In 1866, Italy gained Venetia. Mazzini often spoke out against how Italy was being united. In 1867, he refused a seat in the Italian Parliament. In 1870, he tried to start a rebellion in Sicily. He was arrested and imprisoned. In October, he was freed after an amnesty was declared when the Kingdom finally took Rome. He returned to London in December.

Mazzini died in Pisa in 1872, at the age of 66. His funeral was held in Genoa, with 100,000 people attending.

Mazzini's Ideas

Nationalism and Republicanism

Mazzini was an Italian nationalist. He strongly believed in republicanism and wanted a united, free, and independent Italy. Unlike his friend Giuseppe Garibaldi, Mazzini refused to support the monarchy (rule by a king) until Rome was finally taken.

Mazzini and his followers cared about social justice. They discussed ideas with socialists, finding common ground with some of their views. However, Mazzini strongly disagreed with Karl Marx's ideas of class struggle. He believed that different social classes should work together, not fight each other. Mazzini also rejected the idea of individualism, which he felt ignored the importance of community.

Religion and Duty

Mazzini's ideas were deeply influenced by his religious upbringing. He believed in God and a strong sense of spirituality. He was a deist, meaning he believed in a God who created the universe but does not interfere directly. His famous motto was Dio e Popolo ("God and People").

Mazzini saw patriotism as a duty. He believed that loving one's country was a divine mission. He said that the homeland was "the home wherein God has placed us, among brothers and sisters linked to us by the family ties of a common religion, history, and language." He believed that his vision for a new Italy was like a new religion, based on faith in one God and one law.

Mazzini's relationship with the Catholic Church was complex. While he initially supported Pope Pius IX, he later criticized him. He also criticized Protestantism for being too divided.

Thought and Action

Mazzini rejected the idea of "rights of man" that came from the Age of Enlightenment. Instead, he argued that individual rights were a duty. These duties had to be earned through hard work, sacrifice, and good actions. He explained these ideas in his book Doveri dell'uomo ("Duties of Man"), published in 1860.

Mazzini also developed the idea of "thought and action." He believed that thinking and doing must go together. Every idea should lead to an action. He felt it was wrong to separate theory from practice.

Women's Rights

In his book "Duties of Man," Mazzini also called for recognizing women's rights. After meeting many thinkers in Europe, Mazzini decided that equality between men and women was key to building a truly democratic Italy.

He wanted to end the social and legal unfairness that women faced. Mazzini's strong stance brought more attention to women's rights among European thinkers. He helped them see women's rights as a vital goal for renewing old nations and creating new ones. Mazzini greatly admired Jessie White Mario, who was called the "Bravest Woman of Modern Time" by Giuseppe Garibaldi. She joined Garibaldi's Redshirts and reported on the events that led to Italy's unification.

Legacy

Mazzini's political ideas are sometimes called Mazzinianism. His way of seeing the world is known as the Mazzinian conception. These terms were later used by some Italian fascists, like Benito Mussolini, to describe their own political beliefs.

In his book Reminiscences, Carl Schurz wrote about Mazzini and recalled meeting him in London in 1851. While some sources list Mazzini as a Freemason, the Grand Orient of Italy's own website questions if he was a regular member.

In Italy, Mazzini was often seen as a hero. However, some of his own countrymen criticized him. Modern historians generally have a positive view of his contributions. The antifascist Mazzini Society, founded in the United States in 1939 by Italian political refugees, took his name. They served Italy from exile, just as Mazzini had done.

In London, Mazzini lived at 155 North Gower Street. This building now has a special blue plaque to remember him. Another plaque in Clerkenwell, London, also honors Mazzini, calling him "The Apostle of Modern Democracy." A statue of Mazzini can be found in New York's Central Park. The 1973–1974 academic year at the College of Europe was named in his honor.

See also

In Spanish: Giuseppe Mazzini para niños

In Spanish: Giuseppe Mazzini para niños

- Italian nationalism

- Italian unification

- Jessie White Mario

- Giuseppe Garibaldi

- Revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states

- Roman Republic (19th century)

Works

- Warfare Against (1825)

- On Nationality (1852)

- The Duties of Man and Other Essays (1860). J.M. Dent & Sons, London, 1907 ISBN: 1596052198.

- A Cosmopolitanism of Nations: Giuseppe Mazzini's Writings on Democracy, Nation Building, and International Relations Recchia, Stefano, and Urbinati, Nadia, editors. Princeton University Press, 2009.

Articles

- "Is it Revolt or a Revolution?" in Tait's Edinburgh Magazine, June 1840, pp. 385–390

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |