Pisa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pisa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comune di Pisa | |||

|

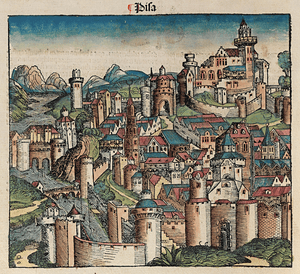

Historic centre of Pisa on the Arno

Pisa Cathedral

Pisa Baptistery

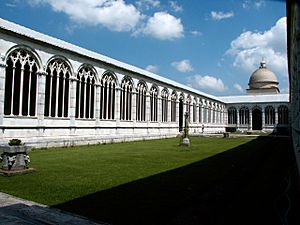

Camposanto Monumentale di Pisa

Piazza dei Cavalieri

|

|||

|

|||

| Country | Italy | ||

| Region | Tuscany | ||

| Province | Pisa (PI) | ||

| Frazioni | Calambrone, Coltano, Marina di Pisa, San Piero a Grado, Tirrenia | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 185 km2 (71 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 4 m (13 ft) | ||

| Population

(July 31, 2023)

|

|||

| • Total | 98,778 | ||

| • Density | 533.9/km2 (1,383/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Pisano Pisan (English) |

||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||

| Postal code |

56121–56128

|

||

| Dialing code | 050 | ||

| Patron saint | San Ranieri | ||

| Saint day | June 17 | ||

Pisa is a famous city in Tuscany, central Italy. It sits right on the Arno River, close to where the river meets the sea. While Pisa is known around the world for its amazing leaning tower, the city has much more to offer. You can find over twenty historic churches, many old palaces, and bridges crossing the Arno. A lot of Pisa's beautiful buildings were paid for by its past as a powerful trading city.

Pisa is also home to important universities. The University of Pisa started way back in the 12th century. There's also the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, founded by Napoleon in 1810, and the Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies.

Contents

History of Pisa

How Pisa Got Its Name

Many historians believe the name Pisa comes from an old Etruscan word meaning 'mouth'. This makes sense because Pisa is located at the mouth of the Arno River.

Pisa's Ancient Beginnings

For a long time, people weren't sure about Pisa's exact origins. But in the 1980s and 1990s, archaeologists found many ancient remains. They even found the tomb of an Etruscan prince from the 5th century BC. This proved that Pisa was an Etruscan city and an important port. It traded with other civilizations around the Mediterranean Sea.

Ancient Roman writers also talked about Pisa as an old city. The poet Virgil wrote that Pisa was already a big center in his time. He even called it Alphēae, saying it was founded by people from a Greek city called Pisa.

Pisa was very important for sea travel. Some say it even invented the ram bow, a tool used on ships. Pisa was the only major port on the western coast between Genoa and Ostia. This made it a key base for Roman ships. In 180 BC, it became a Roman colony. Later, Emperor Augustus made it an even more important port.

Even though Pisa was founded on the coast, the Arno and Serchio rivers have brought so much dirt over time that the coastline has moved west. Today, Pisa is about 6 miles (10 km) from the sea. But it was always a "maritime city," with ships sailing right up the Arno River to reach it.

Pisa in the Middle Ages

During the end of the Western Roman Empire, Pisa didn't decline as much as other Italian cities. This was probably because its river system made it easy to defend. In the 7th century, Pisa helped Pope Gregory I by providing ships. Pisa became the main port in the Upper Tyrrhenian Sea. It was a key trading hub between Tuscany and places like Corsica and Sardinia.

After Charlemagne defeated the Lombards in 774, Pisa faced a tough time but quickly recovered. By 930, Pisa became an important county center. In 1003, Pisa had its first communal war against Lucca. To deal with Saracen pirates, Pisa started building up its fleet. This strong navy helped the city grow even more.

Pisa's Golden Age: The 11th Century

Pisa's power as a sea nation grew a lot in the 11th century. It became known as one of the four main maritime republics of Italy.

At this time, Pisa was a very important trading center. It had a large fleet of merchant ships and a strong navy. In 1005, Pisa expanded its power by attacking Reggio Calabria in southern Italy. Pisa was often fighting with Saracens, who were Arab Muslims, for control of the Mediterranean Sea. In 1017, Pisa and Genoa worked together to defeat the Saracen King Mugahid in Sardinia. This victory made Pisa the most powerful city in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

However, when Pisa later pushed Genoa out of Sardinia, a new rivalry began between these two powerful sea republics. Between 1030 and 1035, Pisa defeated several towns in Sicily and conquered Carthage in North Africa. In 1051–1052, Admiral Jacopo Ciurini conquered Corsica, which made Genoa even more upset.

In 1063, Admiral Giovanni Orlandi helped the Normans take Palermo from Saracen pirates. The gold taken from Palermo helped Pisa start building its famous cathedral and other monuments in the Piazza del Duomo.

In 1060, Pisa fought its first battle with Genoa and won. This helped Pisa become even stronger in the Mediterranean. In 1092, Pope Urban II gave Pisa control over Corsica and Sardinia. He also made Pisa an archbishopric, a very important religious center.

Pisa attacked the city of Mahdia in Tunisia in 1088. Four years later, Pisan and Genoese ships helped a Spanish king push a famous warrior, El Cid, out of Valencia. A Pisan fleet of 120 ships also joined the First Crusade. The Pisans were key in capturing Jerusalem in 1099. On their way, they even attacked some Byzantine islands. Pisa and other Italian sea republics used the crusades to set up trading posts and colonies in cities along the eastern coast of the Levant. They gained special rights and were free from taxes in these places. By the 12th century, the Pisan area in Constantinople had grown to 1,000 people. For some years, Pisa was the most important trading and military partner of the Byzantine Empire, even more so than Venice.

Pisa in the 12th Century

In 1113, Pisa, with the help of Pope Paschal II and others, fought a war to free the Balearic Islands from the Moors. Even though the Moors soon took the islands back, the treasures Pisa gained helped them build their amazing cathedral. This made Pisa a very important city in the western Mediterranean.

In the years that followed, Pisa's strong fleet, led by Archbishop Pietro Moriconi, drove away the Saracens. This success in Spain increased the rivalry with Genoa. Pisa's trade in southern France also clashed with Genoa's interests.

The war between Pisa and Genoa started in 1119 and lasted until 1133. They fought on land and sea, mostly with raids and pirate-like attacks.

In 1135, Pope Innocent II helped resolve the conflict with Genoa. This allowed Pisa to join the Pope in his fight against King Roger II of Sicily. Pisa conquered Amalfi in 1136, destroying its ships and attacking nearby castles. This victory brought Pisa to the peak of its power, on par with Venice. Two years later, Pisan soldiers attacked Salerno.

Pisa was a strong supporter of the Ghibelline party, which was loyal to the Holy Roman Emperor. Emperor Frederick I greatly appreciated this. In 1162 and 1165, he gave Pisa important rights. These included control over the Pisa countryside, free trade across the empire, and parts of many cities in the Kingdom of Sicily. These grants showed Pisa's immense power. But they also made other cities like Lucca and Florence angry, as these cities wanted to expand towards the sea. The conflict with Lucca was also about controlling the Via Francigena, a major trade route. Pisa's sudden growth in power also led to another war with Genoa.

Genoa had become very powerful in the markets of southern France. The war started in 1165. Pisa was allied with Provence. The war continued until 1175 without clear winners. Another point of conflict was Sicily, where both cities had special rights. In 1192, Pisa managed to conquer Messina. But this was followed by battles that led to Genoa conquering Syracuse in 1204. Pisa then lost its trading posts in Sicily.

To fight Genoa's power, Pisa strengthened its ties with its Spanish and French bases. It also tried to challenge Venice's control of the Adriatic Sea. In 1180, Pisa and Venice agreed not to attack each other. But after the death of Emperor Manuel Comnenus, Pisa started attacking Venetian ships. Pisa made trade deals with cities like Ancona and Pula. In 1195, a Pisan fleet went to Pola to defend its independence from Venice.

A year later, the two cities signed a peace treaty. But in 1199, Pisa broke it by blocking the port of Brindisi. In the naval battle that followed, Venice defeated Pisa. The war ended in 1206 with a treaty where Pisa gave up its hopes in the Adriatic. From then on, Pisa and Venice often worked together against the growing power of Genoa.

Pisa in the 13th Century

In 1209, Pisa and Genoa tried to settle their rivalry with a 20-year peace treaty. But in 1220, Emperor Frederick II confirmed Pisa's control over the Tyrrhenian coast. This made Genoa and other Tuscan cities angry at Pisa again. Pisa then fought with Lucca and was defeated by the Florentines. Pisa's strong support for the Ghibelline party put it against the Pope, who was fighting the Holy Roman Empire. The Pope even tried to take away Pisa's lands in northern Sardinia.

In 1238, Pope Gregory IX formed an alliance between Genoa and Venice against the empire and Pisa. A year later, he removed Frederick II from the church and called for a council in Rome in 1241. On May 3, 1241, a combined fleet of Pisan and Sicilian ships attacked a Genoese convoy. The Genoese lost 25 ships, and many sailors, cardinals, and a bishop were captured. After this big victory, the council in Rome failed, but Pisa was removed from the church. This was only lifted in 1257. Pisa tried to take advantage of the situation to conquer the Corsican city of Aleria and even attacked Genoa itself in 1243.

However, Genoa quickly recovered. It won back Lerici, which Pisa had conquered earlier, in 1256.

Pisa's growth in the Mediterranean led to changes in its government. The old system with consuls was replaced. In 1230, new leaders named a capitano del popolo (meaning "people's chieftain") as the city's civil and military leader. Despite these changes, the city was troubled by rivalry between two powerful families, the Della Gherardesca and Visconti. In 1254, the people rebelled and chose 12 Anziani del Popolo ("People's Elders") to represent them. They also added new People's Councils, made up of guilds and leaders of people's groups. These councils could approve laws.

The Decline of Pisa

Pisa's decline is often said to have begun on August 6, 1284. In the naval Battle of Meloria, Pisa's larger fleet was defeated by the clever tactics of the Genoese fleet. This defeat ended Pisa's power at sea, and the city never fully recovered. In 1290, the Genoese completely destroyed Porto Pisano, Pisa's port, and even covered the land with salt. Pisa could not recover from losing thousands of sailors at Meloria. Also, the Arno River started changing its course, making it impossible for large ships to reach the city's port. The area also likely became unhealthy with malaria. The final blow came in 1324, when Sardinia was completely lost to the Aragonese.

Pisa, always loyal to the Ghibelline party, tried to regain its power in the 14th century. It even defeated Florence in the Battle of Montecatini (1315). However, after a long siege, Florence occupied Pisa in 1405. The Florentines bribed Pisa's capitano del popolo, Giovanni Gambacorta, who opened the city gate at night. Pisa was never truly conquered by an army in battle. In 1409, Pisa hosted a council to try and solve the Western Schism, a split in the Catholic Church.

In the 15th century, it became harder for Pisa to reach the sea because its port was filling with mud. In 1494, when Charles VIII of France invaded Italy, Pisa declared its independence as the Second Pisan Republic.

This new freedom didn't last long. For 15 years, Florentine troops tried to conquer the city with battles and sieges, but they failed. Pisa's resources were running low. Eventually, the city was sold to the Visconti family from Milan and then to Florence again. Livorno took over as Tuscany's main port. Pisa then became more important for its culture and education, thanks to the University of Pisa, founded in 1343, and later the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa and Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies.

Pisa was the birthplace of the famous scientist Galileo Galilei. Today, it is still an important religious center and a hub for light industry and railways. It suffered damage during World War II.

Since the 1950s, the US Army has had Camp Darby just outside Pisa. Many US military personnel use it as a base for vacations.

Geography and Climate of Pisa

Pisa's Climate

Pisa has a climate that is a mix of humid subtropical and Mediterranean. This means it has cool to mild winters and hot summers. Pisa gets a moderate amount of rain in the summers, with the most rain falling in autumn. Snow is rare. The highest temperature ever recorded was 39.5°C (103.1°F) on August 22, 2011. The lowest was -13.8°C (7.2°F) on January 12, 1985.

| Climate data for Pisa (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

27.9 (82.2) |

30.9 (87.6) |

35.0 (95.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

39.5 (103.1) |

36.2 (97.2) |

30.2 (86.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

39.5 (103.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.5 (52.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

21.3 (70.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

12.1 (53.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.2 (75.6) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.1 (61.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

15.0 (58.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.8 (37.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

11.7 (53.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.8 (7.2) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.8 (47.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−13.8 (7.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 68.0 (2.68) |

63.1 (2.48) |

60.0 (2.36) |

64.9 (2.56) |

61.7 (2.43) |

41.1 (1.62) |

31.9 (1.26) |

40.6 (1.60) |

100.3 (3.95) |

128.7 (5.07) |

131.1 (5.16) |

87.7 (3.45) |

879.1 (34.62) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.9 | 7.2 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 8.6 | 10.4 | 9.3 | 78.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75.2 | 71.9 | 70.9 | 72.5 | 72.0 | 70.6 | 68.4 | 68.9 | 70.3 | 75.0 | 77.9 | 76.8 | 72.5 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

5.2 (41.4) |

8.4 (47.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.1 (39.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 113.2 | 128.4 | 166.3 | 180.8 | 240.9 | 264.9 | 314.5 | 286.8 | 216.1 | 158.1 | 115.0 | 100.7 | 2,285.7 |

| Source: NOAA, (Sun for 1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

Culture and Traditions in Pisa

The Gioco del Ponte Festival

Pisa has a special festival and game called fr:Gioco del Ponte (Game of the Bridge). It was celebrated in some form from the 1200s until 1807. From the late 1400s, the game became a mock battle fought on Pisa's main bridge, the Ponte di Mezzo.

Players wore padded armor. The only weapon allowed was the targone, a strong, shield-shaped board. Hitting below the belt was not allowed. Two teams started at opposite ends of the bridge. The goal was to push back the other team and drive them off the bridge. The fight lasted 45 minutes. Winning or losing was very important to the teams and their supporters. Sometimes, the game ended in a tie, and both sides celebrated.

In 1677, a Dutch artist named Cornelis de Bruijn saw the battle. He wrote about how intense it was, with players getting bloody and bruised heads.

The tradition was brought back in 1927 by college students as a costume parade. In 1935, the king of Italy and his family watched a modern version of the game. Pisans still celebrate it today with varying levels of excitement.

Pisa's Festivals and Events

Pisa hosts several fun festivals and cultural events throughout the year:

- Capodanno pisano (Pisan New Year, March 25)

- Gioco del Ponte (Game of the Bridge)

- Luminara di San Ranieri (a beautiful light festival, June 16)

- Maritime republics regatta (a boat race)

- Premio Nazionale Letterario Pisa (a national literary award)

- Pisa Book Festival

- Metarock (a rock music festival)

- Internet Festival

- San Ranieri regata (another boat race)

- Turn Off Festival (a house music festival)

- Nessiáh (a Jewish cultural festival, November)

Population of Pisa

| Historical population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: ISTAT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main Sights to See in Pisa

The bell tower of the cathedral is Pisa's most famous landmark. But it's just one of many amazing buildings in the city's Piazza del Duomo. This square is also known as Piazza dei Miracoli (Square of Miracles). In this square, you'll find the Duomo (the Cathedral), the Baptistry, and the Campo Santo (the monumental cemetery). These four sacred buildings, along with a hospital and some palaces, make up a medieval complex. An old non-profit group called Opera della Primaziale Pisana has taken care of these buildings since the Cathedral was built in 1063. Medieval walls surround the area.

Other interesting places to visit include:

- Knights' Square (Piazza dei Cavalieri): Here you can see the Palazzo della Carovana. Its front was designed by Giorgio Vasari.

- Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri: This church is also on Knights' Square and was designed by Giorgio Vasari. It has a bust by Donatello and paintings by famous artists. It also holds treasures from sea battles between the Knights of St. Stephan and the Turks.

- St. Sixtus: This small church, built in 1133, is near Knights' Square. It was used for important legal documents and meetings. It is one of the best-preserved early Romanesque buildings in Pisa.

- St. Francis: This church was likely designed by Giovanni di Simone after 1276. It has a single main area, a notable bell tower, and a 15th-century cloister. It contains works by artists like Jacopo da Empoli. The Gherardesca Chapel is where Ugolino della Gherardesca and his sons are buried.

- San Frediano: Built by 1061, this church has three aisles and a 12th-century crucifix. Paintings from the 16th century were added during a restoration.

- San Nicola: This medieval church, built by 1097, was made larger between 1297 and 1313. Its octagonal bell tower is from the 13th century. It has a Madonna with Child painting by Francesco Traini.

- Santa Maria della Spina: A small white marble church along the Arno River. It is a beautiful Gothic building.

- San Paolo a Ripa d'Arno: This church was founded around 952. It was made larger in the mid-12th century, similar to the cathedral. It has a Romanesque Chapel of St. Agatha with a unique pyramid-shaped roof.

- San Pietro in Vinculis: Also known as San Pierino, this 11th-century church has a crypt and a mosaic floor.

- Borgo Stretto: This medieval neighborhood has covered walkways and the Lungarno, which are avenues along the Arno River. It includes the Gothic-Romanesque church of San Michele in Borgo (990). Pisa also has at least two other leaning towers.

- Medici Palace: This palace once belonged to the Appiano family. The Medici family bought it in 1400, and Lorenzo de' Medici stayed here.

- Orto botanico di Pisa: This is the botanical garden of the University of Pisa. It is Europe's oldest university botanical garden.

- Palazzo Reale (Royal Palace): This palace once belonged to the Caetani family. Galileo Galilei showed the planets he discovered to the Grand Duke of Tuscany here. The building was built in 1559 and is now a museum.

- Palazzo Gambacorti: A 14th-century Gothic palace that now holds the city's offices. Its inside has frescoes celebrating Pisa's sea victories.

- Palazzo Agostini: A 15th-century Gothic palace that includes parts of city walls from before 1155. It houses Caffè dell'Ussero, a coffee shop founded in 1775.

- Mural Tuttomondo: A modern mural, the last public work by Keith Haring. It's on the back wall of the convent of the Church of Sant'Antonio, painted in June 1989.

Museums in Pisa

Pisa has many interesting museums:

- Museo dell'Opera del Duomo: This museum shows original sculptures by Nicola Pisano and Giovanni Pisano. It also has the Islamic Pisa Griffin and treasures from the cathedral.

- Museo delle Sinopie: This museum displays the sinopia drawings from the monumental cemetery. These are reddish drawings made before frescoes.

- Museo Nazionale di San Matteo: This museum has sculptures and paintings from the 12th to 15th centuries. It includes works by Giovanni Pisano, Andrea Pisano, and Masaccio.

- Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Reale: This museum shows items that belonged to the families who lived in the Royal Palace. It includes paintings, statues, and armor.

- Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti per il Calcolo: This museum has a collection of scientific instruments. It includes a compass that probably belonged to Galileo Galilei.

- Museo di storia naturale dell'Università di Pisa (Natural History Museum of the University of Pisa): Located outside the city, it has one of Europe's largest collections of whale skeletons.

- Palazzo Blu: This blue building on the Lungarno hosts temporary exhibitions and cultural events.

- Cantiere delle Navi di Pisa - The Pisa's Ancient Ships Archaeological Area: This museum opened in June 2019. It is located inside the 16th-century Medicean Arsenals. It has a great collection of ceramics and amphoras from the 8th century BCE to the 2nd century BC. It also has 32 ships from the 2nd century BCE to the 7th century BC. Four of them are fully preserved, including the Barca C, also called Alkedo. The first boat was found by accident in 1998 near the Pisa San Rossore railway station.

Churches to Visit in Pisa

- Baptistry: Famous for its pulpit from 1260, made by Nicola Pisano.

- San Francesco

- San Frediano

- San Giorgio ai Tedeschi

- San Michele in Borgo

- San Nicola

- San Paolo a Ripa d'Arno

- San Paolo all'Orto

- San Piero a Grado

- San Pietro in Vinculis

- San Sisto

- San Tommaso delle Convertite

- San Zeno

- Santa Caterina

- Santa Cristina

- Santa Maria della Spina

- Santo Sepolcro

Palaces, Towers, and Villas in Pisa

- Palazzo del Collegio Puteano

- Palazzo della Carovana

- Palazzo delle Vedove

- Torre dei Gualandi

- Villa di Corliano

- Leaning Tower of Pisa

Sports in Pisa

Football in Pisa

Football is the most popular sport in Pisa. The local team, A.C. Pisa, currently plays in the Serie B, which is the second-highest football division in Italy. The club had a strong history in the 1980s and 1990s, with several world-class players like Diego Simeone and Christian Vieri. The team plays at the Arena Garibaldi – Stadio Romeo Anconetani, which opened in 1919 and can hold 25,000 fans.

Transportation in Pisa

Pisa's Airport

Pisa has an international airport called Pisa International Airport or Galileo Galilei Airport. It is located in the San Giusto neighborhood. The airport serves many airlines, connecting Pisa to domestic and international destinations.

Pisamover: Connecting Airport to City

The airport is connected to Pisa Centrale railway station by a people mover system called Pisamover. It opened in March 2017. This driverless "horizontal funicular" travels 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) in 5 minutes. It runs every 5 minutes and has a stop at the San Giusto/Aurelia parking station.

Buses in Pisa

The local public transport in Pisa is managed by Autolinee Toscane since November 1, 2021. Pisa has both urban (city) and suburban (out-of-city) bus routes.

- Urban Bus Routes

- LAM Rossa: Cisanello Hospital - Central Station – Duomo – Parking Pietrasantina

- LAM Verde: San Giusto - Central Station - Pratale

- Shuttle E: Lungarno Pacinotti – Park Brennero – La Fontina

- Night LAM: Cisanello–Lungarni (night service)

- Night LAM: Pietrasantina–Lungarni (night service)

- Shuttle Torre: Park Pietrasantina – Largo Cocco Griffi (Duomo)

- Shuttle Cisanello Hospital: Park Bocchette – Cisanello (Hospital)

- 2: San Giusto – Central Station – Porta a Lucca

- 4: Central Station – I Passi

- 5: Putignano – Central Station – C.E.P.

- 6: Central Station – C.E.P. – Barbaricina

- 8: Coltano – Vittorio Emanuele II square

- 12: Viale Gramsci – Ospedaletto (Expò) – Bus Depot CPT

- 13: Cisanello Hospital – Piagge – Central Station – Pisanova

- 14: Cisanello Hospital – Pisanova – Central Station – Piagge

- 16: Viale Gramsci – Ospedaletto – Industrial Zone (some to Località Montacchiello)

- 21: Airport – Central Station – C.E.P.–Duomo – I Passi (night service)

- 22: Central Station – Piagge–Pisanova–Cisanello–Pratale (night service)

- Suburban Bus Routes to/from Pisa

- 10: Pisa–Tirrenia–Livorno (deviation to La Vettola - San Piero a Grado)

- 50: Pisa–Collesalvetti–Fauglia–Crespina

- 51: Collesalvetti–Lorenzana–Orciano

- 70: Pisa–Gello–Pontasserchio

- 71: Pisa – Sant'Andrea in Palazzi – Pontasserchio – San Martino Ulmiano: Pisa

- 80: Pisa–Migliarino–Vecchiano–Filettole

- 81: Pisa–Pontasserchio–Vecchiano

- 110: Pisa–Asciano–Agnano

- 120: Pisa–Calci–Montemagno

- 140: Pisa–Vicopisano–Pontedera

- 150: Pisa–Musigliano–Pettori

- 160: Pisa–Navacchio–Calci – Tre Colli

- 190: Pisa–Cascina–Pontedera

- 875: Pisa – Arena Metato

Trains in Pisa

Pisa has two railway stations for passengers: Pisa Centrale and Pisa San Rossore.

Pisa Centrale is the main station. It connects Pisa directly with many important Italian cities like Rome, Florence, Genoa, and Naples.

Pisa San Rossore is a smaller station near the Leaning Tower. It links Pisa with Lucca and Viareggio.

There used to be a station called Pisa Aeroporto next to the airport. It closed in 2013 to build the people mover.

Motorways Connecting Pisa

Pisa is connected to two major motorways:

- Autostrada A11 from Florence.

- Autostrada A12 linking Genoa to Rosignano. It has exits for Pisa Nord and Pisa Centro – Airport.

Education in Pisa

Pisa is home to the University of Pisa, which is especially known for its studies in Physics, Mathematics, Engineering, and Computer Science. The Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna and the Scuola Normale Superiore are top Italian schools. They are famous for research and educating advanced students.

- The Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa was founded in 1810 by Napoleon. It was a branch of a famous school in Paris. It became a "national university" in 1862.

- The Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies of Pisa is a public university in Pisa. It focuses on applied sciences.

- The University of Pisa is one of the oldest universities in Italy. It was officially founded on September 3, 1343, by Pope Clement VI. However, law classes were taught in Pisa as early as the 11th century. The university has Europe's oldest academic botanical garden, founded in 1544.

Famous People from Pisa

Many notable people have come from Pisa or lived there:

- Giuliano Amato (born 1938), a politician who was a former Prime Minister.

- Andrea Bocelli (born 1958), a famous singer and musician.

- Giosuè Carducci (1835–1907), a poet who won the 1906 Nobel Prize in Literature.

- Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (1920–2016), a politician who was a former President of Italy.

- Leonardo Fibonacci (1170–1250), a famous mathematician.

- Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), a groundbreaking physicist.

- Giovanni Gentile (1875–1944), a philosopher and politician.

- Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639), a painter.

- Count Ugolino della Gherardesca (1214–1289), a nobleman.

- Giovanni Gronchi (1887–1978), a politician who was a former President of Italy.

- Giacomo Leopardi (1798–1837), a poet and philosopher.

- Enrico Letta (born 1966), a politician who was a former Prime Minister of Italy.

- Antonio Pacinotti (1841–1912), a physicist who invented the dynamo.

- Andrea Pisano (1290–1348), a sculptor and architect.

- Bruno Pontecorvo (1913–1993), a nuclear physicist.

- Gillo Pontecorvo (1919–2006), a filmmaker.

Sports Figures from Pisa

- Jason Acuña (born 1973), a stunt performer.

- Sergio Bertoni (1915–1995), a footballer.

- Giorgio Chiellini (born 1984), a footballer.

- Camila Giorgi (born 1991), a tennis player.

Sister Cities of Pisa

Pisa is twinned with several cities around the world:

Acre, Israel (1988)

Acre, Israel (1988) Akademgorodok (Novosibirsk), Russia (1991)

Akademgorodok (Novosibirsk), Russia (1991) Angers, France (1982)

Angers, France (1982) Hangzhou, China (2008)

Hangzhou, China (2008) Iglesias, Italy (2009)

Iglesias, Italy (2009) Jericho, Palestine (2000)

Jericho, Palestine (2000) Kolding, Denmark (2007)

Kolding, Denmark (2007) Niles, United States (1991)

Niles, United States (1991) Ocala, United States (2004)

Ocala, United States (2004) Rhodes, Greece (2009)

Rhodes, Greece (2009) Santiago de Compostela, Spain (2009)

Santiago de Compostela, Spain (2009) Unna, Germany (1996)

Unna, Germany (1996)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pisa para niños

In Spanish: Pisa para niños