Giacomo Leopardi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Giacomo Leopardi

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by S. Ferrazzi, c. 1820

|

|

| Born |

Giacomo Taldegardo Francesco di Sales Saverio Pietro Leopardi

29 June 1798 Recanati, Papal States

|

| Died | 14 June 1837 (aged 38) |

|

Notable work

|

Canti Operette morali Zibaldone |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy

|

| School | Classicism, later Enlightenment, Romanticism |

|

Main interests

|

Poetry, essay, dialogue |

|

Notable ideas

|

Philosophical pessimism |

| Signature | |

Count Giacomo Leopardi (born June 29, 1798 – died June 14, 1837) was an Italian writer, poet, and thinker. He is known as the greatest Italian poet of the 1800s. Many people also see him as one of the most important writers in the world.

Leopardi was a key figure in the Romantic movement. He often thought deeply about life and what it means to be human. This made him known as a profound philosopher. Even though he lived in a quiet town in the Papal States (areas ruled by the Pope), he learned about the big ideas of the Enlightenment. His poems are very emotional and beautiful, making him a central figure in European literature.

Contents

Biography

Giacomo Leopardi was born into a noble family in Recanati, Italy. At that time, the area was part of the Papal States. His father, Count Monaldo Leopardi, loved books and old traditions. His mother, Marchioness Adelaide Antici Mattei, was strict and focused on fixing the family's money problems. These problems were caused by her husband's gambling.

Life at home was very disciplined, especially about religion and money. However, Giacomo had a happy childhood with his younger brother Carlo and sister Paolina. He wrote about these early experiences in his poem Le Ricordanze.

Giacomo started his studies with two priests, as was common for noble families. But he learned most from his father's large library. He read a lot and gained amazing knowledge of classical languages and history. He could read and write Latin, Ancient Greek, and Hebrew very well. However, he didn't have a formal education that encouraged new ideas.

From age twelve to nineteen, he studied constantly. He wanted to escape the strict rules of his home. These intense studies weakened his health. He likely suffered from Pott's disease or ankylosing spondylitis, which are bone conditions. This illness kept him from enjoying simple things in his youth.

In 1817, a classical scholar named Pietro Giordani visited the Leopardi home. He became Giacomo's lifelong friend and gave him hope for the future. But Giacomo felt more and more trapped in Recanati. In 1818, he tried to run away but his father caught him. After this, his relationship with his father got worse, and his family watched him closely.

In 1822, he briefly visited Rome with his uncle. He was very disappointed by the city's corruption and the Church's hypocrisy. He was moved by the tomb of Torquato Tasso, a poet he felt connected to because of their shared sadness. Unlike other writers who had many adventures, Leopardi struggled to escape his family's control. Rome seemed dull compared to the perfect image he had imagined. His health also continued to get worse.

In 1824, a bookstore owner named Stella asked him to write some works in Milan. During this time, he traveled between Milan, Bologna, Florence, and Pisa. In 1827, he met Alessandro Manzoni in Florence, but they didn't agree on many things.

By 1828, Leopardi was very ill and tired from work. He turned down a job offer to be a professor in Germany. That same year, he had to stop working for Stella and return to Recanati. In 1830, a friend helped him get money to return to Florence. This allowed him to live away from Recanati until 1832. Leopardi found friends among those who wanted to free Italy from foreign rule. He believed in freedom and democracy, even though his own ideas were unique and often sad.

Later, he moved to Naples with his friend Antonio Ranieri, hoping the climate would help his health. He died in 1837 during a cholera outbreak. His death was likely caused by lung or heart problems due to his weak body. Thanks to Antonio Ranieri, Leopardi was not buried in a common grave. His tomb was later moved to a park in Naples and became a national monument.

Poetical works

Early writings (1813–1816)

These were challenging years for Leopardi. He began to develop his ideas about Nature. At first, he thought Nature was kind to people, helping them forget their troubles. But by 1819, he started to see Nature as a harsh, destructive force.

Before 1815, Leopardi was mainly a scholar of old texts. After that, he began to focus on literature and beauty. He wrote Pompeo in Egitto ("Pompey in Egypt", 1812) at age fourteen, which was against Julius Caesar. His Storia dell'Astronomia ("History of Astronomy", 1813) collected all known astronomy facts of his time. In Saggio sopra gli errori popolari degli antichi ("Essay on the popular errors of the ancients"), he explored ancient myths. He saw ancient times as the childhood of humanity, full of dreams and myths.

In 1815, he wrote Orazione agli Italiani ("Oration to the Italians"), celebrating Italy's "freedom" after Austrian help. He also translated Batrachomyomachia, a funny poem that made fun of Homer's Iliad.

In 1816, Leopardi published Discorso sopra la vita e le opere di Frontone ("Discourse on the life and works of Fronto"). He then entered a period of crisis. He wrote L'appressamento della morte, a poem where he felt death was near and comforting. His physical pain and eyesight problems got worse. He felt a strong difference between his inner thoughts and his inability to connect with others.

Leopardi stopped his studies of old texts and turned more to poetry. He read Italian and French writers. His view of the world changed. He stopped finding comfort in religion, which was a big part of his childhood. He became more interested in a scientific view of the universe, inspired by thinkers like John Locke.

In 1816, he published Le rimembranze and Inno a Nettuno ("Hymn to Neptune"). The second poem, written in ancient Greek, was so good that many thought it was a real Greek classic. He also translated parts of the Aeneid and the Odyssey. In a letter, Leopardi argued that Italian literature should not just copy foreign works. He believed poets should be original, drawing inspiration from their own feelings.

His friendship with Giordani, which began in 1817, made him move further away from his father's traditional views. In 1818, he wrote All'Italia ("To Italy") and Sopra il monumento di Dante ("On the Monument of Dante"). These were strong, patriotic poems where Leopardi showed his support for liberal and secular ideas.

At this time, he also joined the debate between classicists and romantics in Europe. He supported the classicists in his Discorso di un Italiano attorno alla poesia romantica ("Discourse of an Italian concerning romantic poetry").

In 1817, he fell in love with Gertrude Cassi Lazzari and wrote Memorie del primo amore ("Memories of first love"). In 1818, he published Il primo amore and started writing a diary called the Zibaldone, which he kept for fifteen years.

The first canti (1818)

All'Italia and Sopra il monumento di Dante were the start of his major works. In these two poems, he introduced the idea that too much "civilization" can be bad for life and beauty. In All'Italia, Leopardi mourns soldiers who died in the Battle of Thermopylae and remembers past greatness. In the second poem, he asks Dante to pity Italy's sad state. In the many poems that followed, he gradually stopped using old literary references and common phrases.

In 1819, the poet tried to escape his difficult home life by traveling to Rome, but his father caught him. During this time, his personal sadness grew into his unique idea of philosophical pessimism.

The Idilli (1819–1821)

The six Idilli ("Idylls") followed his first poems. These include Il sogno ("The dream"), L'Infinito ("The Infinite"), La sera del dì di festa ("The evening of the feast day"), Alla Luna ("To the Moon"), La vita solitaria ("The solitary life"), and Lo spavento notturno ("Night-time terror"). Il sogno still had a style like Petrarch, but the others showed his more mature and independent art. In these poems, Leopardi found a way to connect with nature, which helped ease his pain.

In all the idylls, simple moments or the beauty of nature lead to deeper thoughts. These thoughts are about universal pain, how quickly things pass, the heavy weight of eternity, time moving forward, and nature's blind power.

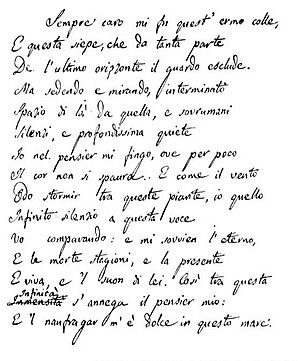

L'Infinito

L'Infinito is one of Leopardi's most famous poems. It combines philosophy and art. In its short, beautiful lines, it captures deep philosophical ideas. The poem is about a concept that is hard for the mind to grasp. The poet describes sitting on a quiet hill. A hedge blocks his view of the horizon, but his mind can imagine endless spaces:

"Sempre caro mi fu quest'ermo colle,

E questa siepe, che da tanta parte

Dell'ultimo orizzonte il guardo esclude."

This can be translated as: "This lonely hill was always dear to me, and this hedge, which blocks so much of the farthest horizon from my sight."

The poem suggests that the hill represents how far human thought can go. But the hedge shows the limits of what humans can understand about life and the universe. The silence is deep. When a breeze blows, it sounds like the present time, bringing to mind all past times and eternity. The poet's mind is filled with new and unknown ideas, but "il naufragar m'è dolce in questo mare" ("shipwreck / seems sweet to me in this sea").

The Canzoni (1820–1823)

Leopardi returned to writing about ancient times. He urged people to find noble old virtues in classical writings.

Ad Angelo Mai

When Angelo Mai discovered a lost work by Cicero, Leopardi wrote the poem Ad Angelo Mai ("To Angelo Mai"). In it, he honored many Italian poets, from Dante and Petrarch to Torquato Tasso and Vittorio Alfieri.

Bruto minore

In Bruto minore ("Brutus the Younger"), Leopardi writes about Caesar's assassin, Brutus. Brutus always believed in honor, virtue, and freedom. He sacrificed everything for these ideals. But he realizes too late that it was all for nothing. He will even die dishonored for his good intentions.

His thoughts lead him to believe that morality has no meaning. He feels that Jove only rewards selfish people and plays unfair games with humans. Humans are more unhappy than animals because animals don't know they are unhappy.

Ultimo canto di Saffo

Sappho is shown as a sad figure. She has a great spirit and mind, but she is trapped in a body that Leopardi describes as miserable. Sappho loved light and beauty, but her life was full of shadows. Nature seemed like a cruel stepmother to her. Her great talent could not free her from this sadness.

In Sappho, Leopardi saw himself. He felt lonely and unhappy, and he gave up on life's joys. This poem expresses a deep, feminine sadness.

The poem starts with a gentle address to the calm nights, which the poet once loved. But the words quickly turn to a violent image of nature in a storm, reflecting her inner turmoil. Leopardi asks painful questions to a fate that denied Sappho beauty. The thought of death cuts these questions short. Sappho wishes the man she loved in vain a small bit of happiness on Earth. She concludes that of all hopes and dreams, only Tartarus (a dark place in Greek mythology) awaits her.

Alla sua donna

In 1823, he wrote Alla sua donna ("To his woman"). In this poem, he expresses his strong wish for an ideal woman. He hoped such a woman, with love, could make life beautiful. In his youth, he dreamed of meeting a perfect, pure, and untouchable woman.

This poem is a hymn to an ideal woman, not a real one. Leopardi realized that what he sought in the women he loved was something beyond them. It was a perfect, almost spiritual idea. This beautiful hymn ends with a passionate wish for this ideal woman to receive his song.

Operette morali (1824)

Between 1823 and 1828, Leopardi stopped writing lyric poetry. Instead, he wrote his major prose work, Operette morali ("Small Moral Works"). This book has 24 unique dialogues and fictional essays. They discuss many themes that were already in his other works. One famous dialogue is Dialogo della Natura e di un Islandese (Dialogue between Nature and an Icelander), where he shares his main philosophical ideas.

Canti Pisano-Recanatesi (1823–1832)

After 1823, Leopardi stopped writing about old myths and famous figures. He felt they had become meaningless. He started writing about suffering in a more "cosmic" way, meaning suffering that affects everyone and everything.

Il Risorgimento

In 1828, Leopardi returned to lyric poetry with Il Risorgimento ("Resurgence"). This poem tells the story of the poet's spiritual journey. He describes a time when he felt no life left in his soul. Then, his feelings and lyrical spirit awakened again. He had been numb, not caring about pain, love, or hope. Life seemed empty until his feelings returned. He accepted life as it was, even with its suffering. This new calm came from understanding his own feelings, even when sadness filled his soul.

Leopardi was happy to feel emotions and pain again after a long period of numbness. With Risorgimento, his poetry came alive. He wrote short poems where a small idea or scene grew into a big vision of life. He remembered images and happy moments from the past.

A Silvia

In 1828, Leopardi wrote A Silvia ("To Silvia"), one of his most famous poems. Silvia was likely the daughter of a servant in his home. She represents the hopes and dreams of a young poet. These hopes are meant to fail too early, just as Silvia's youth is destroyed by illness. People often wonder if Leopardi was in love with her. But the poem is really about a deep and tragic "love of life" itself. Even with all his suffering and sad thoughts, Leopardi could not stop loving humanity, nature, and beauty. However, Leopardi strongly blames Nature for creating the sweet dreams of youth and then causing suffering when "the truth appears" (l'apparir del vero) and shatters them.

Il passero solitario

The poem Il passero solitario ("The Lonely Sparrow") is beautifully structured and has clear images. Leopardi looks at the richness of nature and the inviting world. But the poet has become sad and withdrawn because of his declining health and lost youth. He sees nature's feast but cannot join it. He foresees the regret he will feel later in life for not having lived his youth fully. In this way, he is alone, perhaps even more so than the sparrow. The sparrow lives alone by instinct, but the poet chooses loneliness with his reason and free will.

Le Ricordanze

In 1829, Leopardi had to return to Recanati because he was ill and had money problems. There, he wrote Le Ricordanze ("Memories"). This poem shows many details from his own life. It tells the story of the painful joy he felt seeing places from his childhood and teenage years again. These feelings now faced a harsh reality, and he deeply regretted his lost youth. Brief happiness is shown through Nerina, a character perhaps inspired by the same person as Silvia.

Nerina and Silvia are like dreams, fading images. For Leopardi, life is an illusion, and the only real thing is death. The women in his poems are often just reflections of himself. Life itself, for him, is a fleeting and misleading illusion.

La quiete dopo la tempesta

In 1829, Leopardi wrote La quiete dopo la tempesta ("The Calm After the Storm"). The poem starts with light, comforting lines. But it ends with dark despair. Pleasure and joy are seen as only brief breaks from suffering. The greatest pleasure, he suggests, is found only in death.

Il sabato del villaggio

Il sabato del villaggio ("Saturday in the village"), written the same year, also starts with a calm scene. It describes the people of Recanati preparing for Sunday's rest and celebration. Later, like in the other poem, it expands into deep thoughts about life's emptiness. The joy of waiting for Sunday ends in the less satisfying feast itself. Similarly, all the sweet dreams of youth turn into bitter disappointment.

Canto notturno di un pastore errante dell'Asia

Around late 1829 or early 1830, Leopardi wrote Canto notturno di un pastore errante dell'Asia ("Night-time chant of a wandering Asian sheep-herder"). He was inspired by a book about Central Asian sheep-herders who sang to the full moon. The poem is a dialogue between a sheep-herder and the moon. It begins: "Che fai tu Luna in ciel? Dimmi, che fai, / silenziosa Luna?" ("What do you do Moon in the sky? Tell me, what do you do, / silent Moon?"). The moon stays silent, so the dialogue becomes the sheep-herder's long, urgent monologue. He desperately seeks answers to life's meaninglessness.

The sheep-herder and moon are in an unknown place and time, making their meeting universal. The sheep-herder represents all humanity, and his questions are timeless. The moon represents Nature, a force that is both beautiful and terrifying.

The humble sheep-herder speaks to the moon politely but with deep sadness. The moon's silence makes him question its role, and humanity's role, in life and the world. He defines the "arid truth" that Leopardi often wrote about. In the first part, the sheep-herder sees similarities between his life and the moon's: both rise, follow their paths, and rest. Both lives seem meaningless. However, there's a key difference: human life ends tragically in death, like an old man's journey. The moon, instead, seems eternal and untouched.

In the third part, the sheep-herder asks the moon for answers: What is life? What is its purpose if it ends? What caused everything? But the moon, representing nature, cannot answer. Nature is distant, hard to understand, silent, and perhaps uncaring. The sheep-herder's search for meaning and happiness continues. In the fourth part, he looks at his flock. The sheep live peacefully because they don't know they are unhappy. But he rejects this idea in the final part. He believes that all life, whether moon, sheep, or human, is equally bleak and tragic.

During this time, Leopardi had little contact with his family and had to support himself. In 1830, after sixteen months of "awful night," he accepted money from friends in Tuscany. This allowed him to leave Recanati.

The last Canti (1832–1837)

In his last poems, philosophical questions are most important. One exception is Tramonto della Luna ("Decline of the Moon"), which returns to a gentle, idyllic style.

Il pensiero dominante

In 1831, Leopardi wrote Il pensiero dominante ("The Dominating Thought"). This poem praises love as a powerful, life-giving force, even if it's not returned. However, the poem only shows the desire for love, not its joy. It remains a thought, an illusion. Leopardi usually criticizes everything, but he wants to save love from the world's problems. He wants to protect it deep in his soul. The more lonely he feels, the more he holds onto love. He sees it as faith in his ideal, eternal woman, who eases suffering and disappointment. The poet of universal suffering sings of a good that is greater than life's troubles. For a moment, he seems to sing of possible happiness. But the idea of death as man's only hope returns. He believes the world offers only two beautiful things: love and death.

Il pensiero dominante shows the first joyful moment of love. It almost makes him forget human unhappiness. He feels it's worth enduring a long, painful life to experience such beauty. Il pensiero dominante and Il risorgimento are Leopardi's only joyful poems. Yet, even in these, his sadness always returns. He sees the object of joy as just an illusion created by imagination.

Amore e Morte

The idea of love and death being connected appears again in the 1832 poem Amore e Morte ("Love and Death"). It's a reflection on the pain and destruction that come with love. Love and death are like twins: love creates beautiful things, and death ends all troubles. Love makes people strong and takes away the fear of death. When love fills the soul, it makes one wish for death. Of the two twins, Leopardi dares to call only upon death. Death is no longer the scary figure from Sappho's poem. Instead, it's a young maiden who brings eternal peace. Death is love's sister and a great comforter. Along with love, death is the best the world can offer.

Aspasia

Written in 1834, Aspasia comes from Leopardi's painful experience of unrequited love for Fanny Targioni Tozzetti. Aspasia (representing Fanny) is the only real woman shown in Leopardi's poetry. Aspasia is a clever manipulator whose perfect body hides a corrupt and ordinary soul. She shows that beauty can be deceiving.

The poet, searching for love in vain, takes revenge on fate and the women who rejected him, especially Fanny. Her memory still bothers him. But the poem, inspired by his anger at her behavior, also shows his acceptance of his fate. He is proud to have regained his independence. Aspasia, as a woman, cannot understand the depth of his thoughts.

A se stesso

"A se stesso" (To himself) is an 1833 poem where Leopardi speaks to his own heart. The last illusion, love, is also gone. He once thought love made life worth living, but he changed his mind after Fanny rejected him. She was in love with Antonio Ranieri, Leopardi's best friend. His desires, hopes, and "sweet deceptions" are over. His heart has beaten all his life, but now it's time for it to stop. There is no more room for hope. All he wants is to die, because death is the only good gift nature has given to humans. In "Love and Death," love was still seen as good because it made feelings stronger and made one feel alive. Now, he is doubtful about love too. If he can't have Fanny, nothing is left for him in life. He just wants to die to end all the suffering. Death is a gift because it ends all human pain, which is unavoidable because it's part of human nature, part of nature's cruel plan. The last line, "e l'infinita vanità del tutto," means "and the infinite vanity of the whole." It shows how meaningless human life and the world are.

La ginestra

In 1836, while staying near Torre del Greco on the slopes of Vesuvius, Leopardi wrote his final poetic message, La Ginestra ("The Broom"). It's also known as Il Fiore del Deserto ("The flower of the desert"). The poem has 317 lines and uses free verse. It is the longest of all his Canti and starts unusually. Unlike his other poems, this one begins with a scene of desolation. Then, it switches between the beautiful view and the starry night sky. This poem is the best example of his "new poetic" style, which he had been trying since the 1830s.

Leopardi describes how small the world and humans are compared to the universe. He talks about how uncertain human life is, always threatened by nature's whims. These are not rare problems, but constant ones. He makes fun of human arrogance and belief in progress. Humans hope to live forever, even though they know they will die. He concludes that helping each other is the only defense against their common enemy: nature.

In this poem, Leopardi shares his vast thoughts about humanity, history, and nature. It includes parts of his own life: the places he describes are those around him in his later years. It also shows a man who is poor and weak but brave enough to know his true condition. The humble ginestra plant, living in desolate places without giving up to nature's force, is like this ideal person. This person rejects all illusions and doesn't ask for impossible help from Heaven or Nature.

Mount Vesuvius, the volcano that brings destruction, is a major presence in the poem. The only certain truth is death, which humans must face. They must give up all illusions and realize their sad condition. This awareness will end their hatred for each other.

It is a long poem with brilliant changes in tone. It goes from grand and tragic descriptions of the threatening volcano and barren lava fields to sharp arguments. It shows how tiny Earth and humans are in the vast universe. It looks at centuries of human history, always under nature's unchanging threat. Then, it shifts to gentle notes about the "flower in the desert." This flower has complex symbolic meanings: pity for human suffering and the dignity humans should have when facing nature's crushing force.

La Ginestra marks a key change and closes Leopardi's poetic career, along with Il tramonto della Luna. The poem repeats his strong anti-optimistic and anti-religious arguments, but in a new, more democratic way. Here, Leopardi no longer denies the possibility of social progress. He tries to build an idea of progress based on his own sadness about life.

Il tramonto della Luna

Il tramonto della Luna ("The Waning of the Moon"), his last poem, was written in Naples shortly before he died. The moon fades, leaving nature in darkness. This is like youth passing away, leaving life dark and empty. The poet seems to sense that his own death is near.

In 1845, his friend Ranieri published the final edition of the Canti, as Leopardi had wished.

Philosophical works

The Zibaldone

The Zibaldone di pensieri is a collection of Leopardi's personal thoughts, short sayings, philosophical ideas, and notes. It was published after his death in 1898.

In the Zibaldone, Leopardi compares the innocent and happy state of nature to modern man. He believed that too much reason, which rejects the necessary illusions of myth and religion, only brings unhappiness. The Zibaldone shows Leopardi's journey through his own life and ideas. It's a mix of philosophical notes, plans, writings, moral thoughts, and observations. Even though Leopardi was not part of the main philosophical discussions of his time, he developed very new and challenging ideas about the world. Some people even call Leopardi the "father of nihilism" (the belief that life is meaningless).

Images for kids

-

Pietro Tenerani: Monument to Clelia Severini (1825), which inspired the poem Sopra un bassorilievo antico sepolcrale.

-

Bust of Homer.

See also

In Spanish: Giacomo Leopardi para niños

In Spanish: Giacomo Leopardi para niños

- Evgeny Baratynsky – Russian poet often compared to Leopardi