Horace facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Horace

|

|

|---|---|

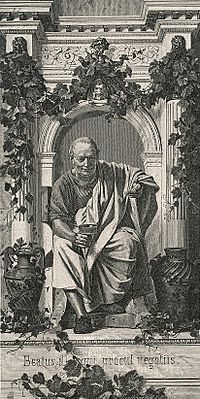

Horace, as imagined by Anton von Werner

|

|

| Born | Quintus Horatius Flaccus 8 December 65 BC Venusia, Italy, Roman Republic |

| Died | 27 November 8 BC (age 56) Rome |

| Resting place | Rome |

| Occupation | Soldier, scriba quaestorius, poet, senator |

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | Lyric poetry |

| Notable works | Odes "The Art of Poetry" |

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (born December 8, 65 BC – died November 27, 8 BC), known as Horace, was a very important Roman poet. He wrote beautiful lyric poems during the time of Augustus, who was the first Roman Emperor. Many people, like the writer Quintilian, thought his collection of poems called Odes were the best Latin lyric poems ever. They said he could be grand and serious, but also charming and clever with his words.

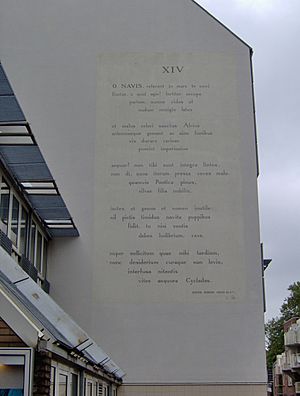

Horace also wrote other kinds of poetry. He created elegant verses called Satires and Epistles, which were often funny but also had serious messages. He also wrote sharp, critical poems called Epodes. An ancient writer named Persius said that Horace could gently point out people's flaws while making them laugh.

Horace's life happened during a huge change in Rome. The Roman Republic was ending, and the Roman Empire was beginning. He was a soldier in the army that lost the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC. Later, he became friends with Maecenas, a close advisor to Augustus. Horace then became a voice for the new government. Some people believe he kept his independence, while others thought he was simply loyal to the emperor.

Contents

Horace's Life Story

Horace is special because he wrote a lot about himself in his poems. He shared details about his personality, how he grew up, and his way of life. This was unusual for ancient poets. We also know more about him from a short but helpful biography written by Suetonius.

Growing Up: Horace's Early Years

Horace was born on December 8, 65 BC, in Venusia, a town in southern Italy. His hometown was on a busy trade route between two regions, Apulia and Lucania. Because of this, many different Italian languages were spoken there. This might have helped him develop his love for language. He might have even known some Greek words as a young boy.

Horace's father was likely a former slave from Venusia. He had been captured by Romans during a war, but he managed to gain his freedom. He worked hard and became successful. Horace said his father was a 'coactor', which could mean he was like an auctioneer or a banker.

His father spent a lot of money to make sure Horace got a good education. He even went with Horace to Rome to watch over his schooling and teach him good values. Horace later wrote a poem praising his father, which many consider a beautiful tribute. Horace never mentioned his mother in his poems, so he might not have known much about her.

Horace's Adult Life and Education

After his father likely passed away, Horace left Rome. He went to Athens, Greece, at age 19 to continue his education. Athens was a famous center for learning in the ancient world. He studied different philosophies there, especially Epicureanism and Stoicism, which greatly influenced him. He also spent time with other young Roman nobles, like the son of Cicero. In Athens, he learned a lot about ancient Greek poetry.

Joining the Army: A Young Soldier

Rome faced many problems after Julius Caesar was killed. Marcus Junius Brutus came to Athens to gather support for the Roman Republic. Brutus was popular in Athens and recruited young students, including Horace. Horace became a military tribune, a high-ranking officer in the army. This job was usually for men from important families, which made some of his fellow soldiers jealous.

Horace learned about military life while marching through northern Greece. In 42 BC, Octavian (who later became Emperor Augustus) and Mark Antony defeated Brutus's republican army at the Battle of Philippi. Horace later joked that he ran away from the battle without his shield. He compared himself to famous poets like Alcaeus and Archilochus, who also left their shields behind in battle.

Returning Home and Becoming a Poet

Octavian offered forgiveness to his opponents, and Horace quickly accepted. When he returned to Italy, he faced another challenge: his family's land in Venusia was taken by the government. This land was given to soldiers who had fought in the war. Horace later said this made him poor and led him to try writing poetry. However, poetry didn't pay much money. It mostly helped him meet other poets and wealthy supporters.

Around this time, he got a job as a scriba quaestorius. This was a civil service job at the Treasury. It paid well and didn't require too much work, so he had time to write. This is when he started writing his Satires and Epodes.

Becoming a Famous Poet

Horace's Epodes are a type of poetry called iambic poetry. This kind of poetry often uses strong, sometimes harsh, language to criticize people. It was meant to encourage citizens to do their part for society. Horace based these poems on the style of Archilochus.

His Satires were unique to Roman literature. Horace used them to discuss social and ethical issues in Rome. He changed satire from a public criticism to a more private reflection. Slowly, he started to gain the attention of Octavian's supporters. His friend, the poet Virgil, helped him get introduced to Maecenas, who was Octavian's main helper.

Horace said his friendship with Maecenas and later with Augustus was based on respect. He gained support and money, and the politicians gained a poet who could support their ideas. Horace had fought for the Republic, so he might have felt conflicted about his new role. However, most Romans believed the civil wars were caused by rivalries, and Horace seemed to accept that Augustus's rule was Rome's best chance for peace.

In 37 BC, Horace traveled with Maecenas to Brundisium. He wrote about this journey in a poem, describing funny events and meeting friends like Virgil. This trip was actually political, as Maecenas was going to negotiate a treaty with Mark Antony. Horace cleverly kept the political details out of his poem.

Horace also seemed to have been with Maecenas during some of Octavian's naval battles. He briefly mentioned a near-drowning incident in 36 BC. There are also hints that he was with Maecenas at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, where Octavian defeated Antony.

By this time, Horace had received a famous gift from Maecenas: his Sabine farm. This gift probably allowed him to leave his job at the Treasury or at least spend less time there. It showed his connection to Octavian's government.

A Roman Knight

Horace then focused on writing Odes 1–3. He used forms and themes from ancient Greek lyric poetry. His new life on his Sabine farm, away from Rome, might have helped him feel more free to write. Even when his poems touched on public matters, they still emphasized the importance of private life.

However, his work from 30–27 BC showed his growing closeness to the government and its ideas. For example, in Odes 1.2, he praised Octavian using very grand language. The name Augustus, which Octavian took in 27 BC, first appears in Horace's Odes 3.3 and 3.5. Between 27–24 BC, his Odes mentioned foreign wars in places like Britain, Arabia, Spain, and Parthia. When Augustus returned to Rome in 24 BC, Horace greeted him as a beloved ruler.

Horace was disappointed with how Odes 1–3 were received by the public. He thought it was because of jealousy among people at the emperor's court. This disappointment might have led him to write verse letters instead. He wrote his first book of Epistles to various friends in a polite style that showed his new social status as a knight.

In the first poem of this book, he said he was more interested in philosophy than poetry. While the collection shows some ideas from Stoic philosophy, it doesn't deeply explore ethics. Maecenas was still his main friend, but Horace started to show more independence, politely turning down invitations from his patron. In the last poem of Epistles 1, he said he was 44 years old, "small, fond of the sun, prematurely grey, quick-tempered but easily calmed."

According to Suetonius, Augustus himself asked Horace to write the second book of Epistles. Augustus was a great letter-writer and even asked Horace to be his personal secretary. Horace said no to being a secretary but agreed to write the verse letter for the emperor. This letter, published around 11 BC, celebrated the military victories of Augustus's stepsons, Drusus and Tiberius. These letters also focused a lot on literary theory and criticism.

Horace explored literary themes even more in Ars Poetica (The Art of Poetry), which was written like a letter and might have been his last poem. He was also asked to write odes celebrating the victories of Drusus and Tiberius. He wrote a special hymn, Carmen Saeculare, to be sung at the Secular Games, an old festival that Augustus brought back to life.

Horace died at 56 years old, not long after his friend Maecenas. He was buried near Maecenas's tomb. Both men left their property to Augustus, which was a common honor for the emperor's friends.

Horace's Works

The exact dates when Horace's works were published are not perfectly known, and scholars often discuss the order. Here is a likely timeline:

- Satires 1 (around 35–34 BC)

- Satires 2 (around 30 BC)

- Epodes (30 BC)

- Odes 1–3 (around 23 BC)

- Epistles 1 (around 21 BC)

- Carmen Saeculare (17 BC)

- Epistles 2 (around 11 BC)

- Odes 4 (around 11 BC)

- Ars Poetica (around 10–8 BC)

Writing Style and Influences

Horace used traditional rhythms and structures in his poems, which he borrowed from ancient Greece. He used hexameters in his Satires and Epistles, and iambs in his Epodes. These were fairly easy to adapt into Latin. His Odes used more complex rhythms, like alcaics and sapphics, which were sometimes harder to fit into Latin.

Even though he used traditional forms, Horace saw himself as part of a new, refined style of poetry. He was especially influenced by Hellenistic poetry, which valued short, elegant, and polished writing.

Horace's poems were not just for a small group of friends. They were written for a wide audience, as a public form of art. He presented himself as someone who sought peace of mind and avoided greed. This idea of moderation fit well with Augustus's plans to improve public morals in Rome.

Horace often followed the examples of famous poets from different genres. For example, he looked to Archilochus for his Epodes, Lucilius for his Satires, and Alcaeus for his Odes. He later broadened his style because his models didn't always fit the real world he lived in.

Archilochus and Alcaeus were Greek aristocrats whose poetry had a clear social and religious purpose for their audiences. When brought to Rome, their style became more of an artistic choice. Horace proudly said he brought the spirit of Archilochus's iambic poetry to Latin, but without attacking anyone personally. His Epodes were based on Archilochus's "blame poetry," but Horace avoided targeting real people. Instead, he aimed for humor and often presented himself as a weak critic of his time.

Horace also claimed to be the first Latin poet to use the lyrical methods of Alcaeus. He was indeed the first to consistently use Alcaic meters and themes like love, politics, and parties. He also imitated other Greek lyric poets, often starting an ode with a reference to a Greek original and then changing it to his own ideas.

The satirist Lucilius was the son of a senator and could criticize others freely. Horace, however, was the son of a freedman, so he had to be more careful. Lucilius was a strong patriot who spoke his mind directly. Horace, instead, used a more indirect and ironic style of satire, making fun of general types of people rather than specific individuals. His freedom was more about his philosophical outlook than a political privilege. His Satires are easier to read than his Odes, but they are still very structured compared to Lucilius's poems, which Horace sometimes criticized for being messy.

The Epistles are considered some of Horace's most creative works. There was nothing quite like them in Greek or Roman literature. While some poems had been written like letters before, Horace was the first to create an entire collection of verse letters, especially ones focused on philosophical ideas. He used the refined style he developed in his Satires for this new, more serious type of writing. Horace's skill with words is clear in all his poems, and he often improved his handling of each style over time. For example, his second book of Satires, which uses dialogue to show human foolishness, is generally seen as better than the first book, where he mostly spoke his own ideas. Still, the first book contains some of his most popular poems.

Main Ideas in Horace's Poetry

Horace explored several connected ideas throughout his writing career. These included politics, love, philosophy, ethics, his own role in society, and poetry itself. His Epodes and Satires are forms of "blame poetry" and often connect with the moral teachings of Cynicism. This often appears as references to the philosopher Bion of Borysthenes, but it was more of a literary game than a strict philosophical belief.

By the time he wrote his Epistles, he was more critical of Cynicism and other impractical philosophies.

The Satires also show a strong influence from Epicureanism, with many references to the Epicurean poet Lucretius. For example, the Epicurean idea of carpe diem (seize the day) inspired Horace's jokes about his own name (Horatius sounds like hora, meaning hour) in Satires 2.6. The Satires also include ideas from Stoicism, Peripatetic philosophy, and Plato. Overall, the Satires mix different philosophical ideas without a strict order, which was typical for this type of poetry.

The Odes cover a wide range of topics. Over time, Horace became more confident in expressing his political views. Even though he is often seen as a very intellectual lover, he was clever at showing strong emotions. The Odes combine different philosophical ideas, with references to doctrines in about a third of Odes Books 1–3. These range from lighthearted (1.22, 3.28) to serious (2.10, 3.2, 3.3). Epicureanism is the strongest influence, appearing in about twice as many odes as Stoicism.

Some odes combine these two influences in interesting ways. For example, Odes 1.7 praises Stoic strength and public duty while also suggesting private pleasures among friends. While Horace generally preferred the Epicurean lifestyle, he was open to different ideas. In Odes 2.10, he even suggests Aristotle's golden mean (finding a balance) as a solution for Rome's political problems.

Many of Horace's poems also reflect on poetry itself, the tradition of lyric poetry, and what poetry is for. Odes 4, which Augustus likely asked him to write, takes the themes of the first three books to a new level. This book shows more poetic confidence after his public performance of Carmen Saeculare (Century Hymn) at a festival organized by Augustus. In it, Horace speaks directly to Emperor Augustus with more confidence. He declares his power to make those he praises famous forever through his poetry. This book is the least philosophical of his collections, except for the twelfth ode, which is addressed to the dead Virgil as if he were still alive. In that ode, the epic poet (Virgil) and the lyric poet (Horace) are linked to Stoicism and Epicureanism, creating a mix of sadness and sweetness.

The first poem of the Epistles sets the philosophical tone for the rest of the collection: "So now I put aside both verses and all those other games: What is true and what befits is my care, this my question, this my whole concern." His statement about giving up poetry for philosophy is meant to be a bit unclear. This ambiguity is a key feature of the Epistles. It's not always clear if the people he's writing to are being honored or criticized. Although he appears as an Epicurean, he suggests that philosophical choices, like political and social ones, are a matter of personal preference. He shows the ups and downs of a philosophical life more realistically than most philosophers do.

Translations

- The Ars Poetica was first translated into English by Thomas Drant in 1556. Later, Ben Jonson and Lord Byron also translated it.

- John Dryden included adaptations of three of the Odes and one Epode in his work Sylvæ (1685).

- Philip Francis translated The Odes, Epodes, and Carmen Seculare (1742) and The Satires, Epistles, and Art of Poetry (1746). Samuel Johnson liked these translations.

- C. S. Calverley included versions of ten of the Odes in his Verses and Translations (1860).

- John Conington translated The Odes and Carmen Sæculare of Horace (1863) and The Satires, Epistles and Ars Poëtica of Horace (1869).

- Theodore Martin published The Odes of Horace, Translated Into English Verse, with a Life and Notes (1866).

- James Michie's The Odes of Horace (1964) included some Odes in their original Sapphic and Alcaic meters.

- More recent translations of the Odes include those by David West (free verse) and Colin Sydenham (rhymed).

- In 1983, Charles E. Passage translated all of Horace's works using their original meters.

- Stuart Lyons wrote Horace's Odes and the Mystery of Do-Re-Mi (rhymed).

See also

In Spanish: Horacio para niños

In Spanish: Horacio para niños

- Carpe diem

- Horatia gens

- List of ancient Romans

- Otium

- Prosody (Latin)

- Translation

- Horace's Villa

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |