Miguel de Unamuno facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Miguel de Unamuno

|

|

|---|---|

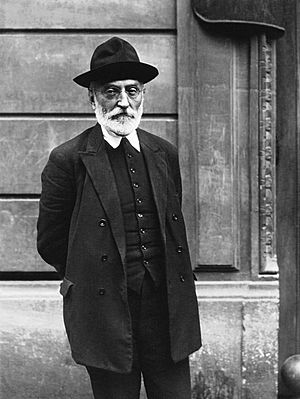

De Unamuno in 1925

|

|

| Born |

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo

29 September 1864 |

| Died | December 31, 1936 (aged 72) Salamanca, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Alma mater | Complutense University of Madrid |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Positivism Existentialism |

|

Main interests

|

Philosophy of religion, political philosophy |

|

Notable ideas

|

Agony of Christianity |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (born September 29, 1864 – died December 31, 1936) was an important Spanish writer and thinker. He was an essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, and philosopher. He also taught Greek and Classics at the University of Salamanca, where he later became the rector (the head of the university).

One of his most famous philosophical essays was The Tragic Sense of Life (1912). His well-known novel was Abel Sánchez: The History of a Passion (1917), which explored the old story of Cain and Abel in a new way.

Contents

Miguel de Unamuno's Life Story

Miguel de Unamuno was born in Bilbao, a port city in the Basque Country, Spain. His parents were Félix de Unamuno and Salomé Jugo. When he was young, he was very interested in the Basque language, which he could speak.

Unamuno wrote in many different styles, including essays, novels, poetry, and plays. He was a modernist writer, meaning he helped break down the usual rules between these different types of writing. Some people debate if he was part of the "Generation of '98." This was a group of Spanish writers and thinkers who came together after Spain lost its last colonies in 1898.

Unamuno wanted to be a philosophy professor. However, it was hard to get a philosophy job in Spain because politics played a big role. So, he became a Greek professor instead.

In 1901, Unamuno gave a famous speech about the Basque language. He argued that it wasn't suitable for science or literature. According to Azurmendi, Unamuno's views on the Basque language changed as his political ideas about Spain developed.

Unamuno was also very active in Spain's intellectual life. He was the rector of the University of Salamanca twice. He served from 1900 to 1924 and again from 1930 to 1936. This was a time of big social and political changes in Spain. In the 1910s and 1920s, he became a strong supporter of social liberalism. This is a political idea that supports individual freedoms but also believes the government should help people.

Unamuno linked his liberal ideas to his hometown of Bilbao. He believed Bilbao's trade and connections with the world made its people independent thinkers. This was different from the traditional views of some other parts of Spain. During World War I, Unamuno supported the Allied side, even though Spain was officially neutral. He saw the war as a fight against the German Empire's monarchy and also against the monarchy in Spain. He often criticized King Alfonso XIII.

Exile and Return

In 1924, the dictator General Miguel Primo de Rivera removed Unamuno from his university positions. This happened because Unamuno openly criticized Primo de Rivera's rule. Many other Spanish thinkers protested this decision. Unamuno lived in exile until 1930. First, he was sent to Fuerteventura, one of the Canary Islands. His house there is now a museum. He then escaped to France, living in Paris for a year before moving to Hendaye, a town in the French Basque Country right on the border with Spain.

When Primo de Rivera's dictatorship ended in 1930, Unamuno returned to Spain. He became rector of the University of Salamanca again. It is said that on his first day back, he started his lecture by saying, "As we were saying yesterday..." This was a famous line used by a monk named Fray Luis de León after he returned from four years in prison.

After the dictatorship fell, Spain became the Second Republic. Unamuno was elected as a representative for the Republican/Socialist party. He even led a big parade where he raised the Republic's flag. He always tried to be moderate and avoided extreme political or anti-religious views. In 1932, he spoke out against some of Manuel Azaña's anti-religious policies. He said that even the old Spanish Inquisition had some legal rules, but now there was a police force acting out of fear.

Unamuno's dislike for Manuel Azaña's government grew. On August 22, 1936, Unamuno was removed from his rector position again. The government even took his name off streets and replaced it with Simón Bolívar's.

Views on the Spanish Civil War

Unamuno first supported Franco's military uprising in the Spanish Civil War. He believed it was needed to bring order to Spain. When a journalist asked him why he supported the military over the Republic he helped create, Unamuno said it was a fight for civilization, not against the liberal Republic.

However, Unamuno soon turned against Franco's side because of their harsh methods. He said the military revolt would lead to a type of Catholicism that wasn't truly Christian and a "paranoid militarism" from colonial wars.

In 1936, Unamuno had a public argument with Nationalist general Millán Astray at the university. He criticized Astray and parts of the Nationalist group. Soon after, Unamuno was removed as rector for the second time.

On November 21, he wrote to an Italian philosopher, saying that "The barbarism is everywhere. It is a system of terror on both sides."

Unamuno was very sad and was placed under house arrest by Franco's forces until he died.

Confrontation with Millán Astray

On October 12, 1936, the Spanish Civil War had been going on for almost three months. A celebration at the University of Salamanca brought together many different people. These included the Archbishop of Salamanca, Carmen Polo Martínez-Valdés (Franco's wife), General José Millán Astray, and Unamuno himself.

Unamuno had supported Franco's uprising because he thought it would bring order. On that day, he was even representing General Franco at the event. The Republican government had removed Unamuno from his permanent rector position, but the rebel government had given it back to him.

Death

Unamuno died on December 31, 1936. He was still under house arrest by the military forces controlling Salamanca. He died from breathing in gases from a brazier (a heater) during a one-hour interview with a visitor.

Unamuno's Writings and Ideas

Fiction Novels and Stories

- Paz en la guerra (Peace in War) (1897) – This novel explores how people relate to themselves and the world, especially when facing death. It's based on his childhood experiences during a war in Bilbao.

- Amor y pedagogía (Love and Pedagogy) (1902) – A funny and sad novel that makes fun of some scientific ideas about society.

- El espejo de la muerte (The Mirror of Death) (1913) – A collection of short stories.

- Niebla (Mist) (1914) – One of Unamuno's most important works. He called it a nivola to show it was different from a typical novel.

- Vida de Don Quijote y Sancho (Our Lord Don Quixote) (1914) – Another key work. It's seen as one of the first books to apply ideas from existentialism to Don Quixote. Unamuno felt that Miguel de Cervantes hadn't told the story of Don Quixote well. He wanted to tell it the way he thought it should be.

- Abel Sánchez (1917) – A novel that uses the story of Cain and Abel to explore the feeling of envy.

- Tulio Montalbán (1920) – A short novel about how a person's public image can hide their true self. This was a problem Unamuno, being famous, understood well.

- Tres novelas ejemplares y un prólogo (Three Exemplary Novels and a Prologue) (1920) – A well-known work with a famous introduction. The title is a nod to Miguel de Cervantes's famous Novelas ejemplares.

- La tía Tula (Aunt Tula) (1921) – His last long novel, about motherhood. He had explored this topic before in other works.

- Teresa (1924) – A story with romantic poetry, showing how an ideal person can be created through writing.

- Cómo se hace una novela (How to Make a Novel) (1927) – This book looks closely at how one of Unamuno's own novels was made.

- Don Sandalio, jugador de ajedrez (Don Sandalio, Chess Player) (1930).

- San Manuel Bueno, mártir (Saint Emmanuel the Good, Martyr) (1930) – A short story that brings together almost all of Unamuno's ideas. It's about a heroic priest who has lost his faith in life after death. But he keeps his doubts secret from his church members, because he knows their faith helps them live.

Unamuno's Philosophy

Unamuno's philosophy wasn't a strict system of rules. Instead, he often questioned all systems and focused on faith itself. When he was young, he was influenced by rationalism (thinking based on reason) and positivism (thinking based on facts). He also wrote articles showing his support for socialism and his worry about Spain's situation.

An important idea for Unamuno was intrahistoria. He believed that history could be best understood by looking at the small, everyday lives of ordinary people. He thought these small stories were more important than big events like wars or political agreements.

In the late 1800s, Unamuno had a religious crisis and moved away from positivist philosophy. Then, in the early 1900s, he developed his own ideas, influenced by existentialism. This is a philosophy that focuses on human existence and freedom. Unamuno believed life was tragic because we know we will die. He thought much of what humans do is an attempt to live on in some way after death.

He summarized his own belief: "My religion is to seek for truth in life and for life in truth, even knowing that I shall not find them while I live." He discussed the differences between faith and reason in his most famous work, Del sentimiento trágico de la vida (The Tragic Sense of Life, 1912).

Unamuno also had a lifelong interest in origami (paper folding). He used paper figures to express his philosophical ideas. He even created the word "cocotología" to describe the art of paper folding.

Some of Unamuno's works, like The Agony of Christianity (1931) and Saint Emmanuel the Good, Martyr (1930), were put on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum. This was a list of books that the Catholic Church forbade its members from reading.

After his early support for socialism, Unamuno moved towards liberalism. His idea of liberalism, which he explained in essays like La esencia del liberalismo (1909), tried to combine great respect for individual freedom with a government that helps people more. This made his views closer to social liberalism.

Unamuno was very knowledgeable about Portuguese culture, literature, and history. He believed it was important for Spanish people to know about Portuguese writers, just as they would Catalan writers. He thought that countries in the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) should connect through sharing their cultures. However, he was against any idea of a single "Iberian Federalism" (a political union).

Unamuno was one of several important thinkers between the two World Wars. Like others, he tried to stop political ideas from taking over intellectual life in the West.

Poetry as Expression

For Unamuno, poetry was a way to express deep spiritual problems. His poems explored the same themes as his other writings: spiritual pain, the sadness caused by God's silence, and ideas about time and death.

Unamuno liked traditional poetry styles. While his early poems didn't rhyme, he later started using rhyme in his works.

Some of his important poetry collections include:

- Poesías (Poems) (1907) – His first poetry book, where he introduced the main themes of his poetry: religious struggles, Spain, and home life.

- Rosario de sonetos líricos (Rosary of Lyric Sonnets) (1911)

- El Cristo de Velázquez (The Christ of Velázquez) (1920) – A religious work that looks at the figure of Christ from many angles.

- Andanzas y visiones españolas (1922) – A travel book where Unamuno shares his strong feelings and observations about Spanish landscapes.

- Rimas de dentro (Rhymes from Within) (1923)

- Rimas de un poeta desconocido (Rhymes from an Unknown Poet) (1924)

- De Fuerteventura a París (From Fuerteventura to Paris) (1925)

- Romancero del destierro (Ballads of Exile) (1928)

- Cancionero (Songbook) (1953, published after his death)

Drama and Plays

Unamuno's plays show how his philosophical ideas developed over time.

His plays like La esfinge (The Sphinx) (1898) and La verdad (Truth) (1899) focused on questions like individual spirituality, faith, and having a double personality.

In 1934, he wrote El hermano Juan o El mundo es teatro (Brother Juan or The World is a Theatre).

Unamuno's plays were simple in style. He removed fancy tricks and focused only on the inner struggles and feelings of his characters. This simple style was influenced by classical Greek theatre. He cared most about showing the drama happening inside the characters, because he saw plays as a way to understand life.

By using simple language and presentation, Unamuno's plays helped pave the way for a new era of Spanish theatre. This new era included writers like Ramón del Valle-Inclán, Azorín, and Federico García Lorca.

See also

In Spanish: Miguel de Unamuno para niños

In Spanish: Miguel de Unamuno para niños