Second Spanish Republic facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Spanish Republic

República Española

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1931–1939 | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Motto: Plus Ultra (Latin)

Further Beyond |

|||||||||||

|

Anthem: Himno de Riego

Anthem of Riego |

|||||||||||

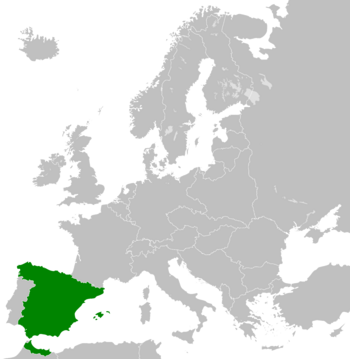

European borders of the Second Spanish Republic, as well as the Spanish protectorate in Morocco

|

|||||||||||

| Capital and largest city

|

Madrid | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Spanish, Spaniard | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

|

• 1931–1936

|

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora | ||||||||||

|

• 1936 (interim)

|

Diego Martínez Barrio | ||||||||||

|

• 1936–1939

|

Manuel Azaña | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

|

• 1931 (first)

|

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora | ||||||||||

|

• 1937–1939 (last)

|

Juan Negrín | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Congress of Deputies | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||||

|

• Proclamation

|

14 April 1931 | ||||||||||

| 9 December 1931 | |||||||||||

| 5–19 October 1934 | |||||||||||

| 17 July 1936 | |||||||||||

| 1 April 1939 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish peseta | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

The Spanish Republic (also known as the Second Spanish Republic) was the government of Spain from 1931 to 1939. It began on April 14, 1931, when King Alfonso XIII left the country. It ended on April 1, 1939, after losing the Spanish Civil War to the Nationalists, led by General Francisco Franco.

After the Republic was declared, a temporary government was set up. In December 1931, the 1931 Constitution was approved. For the next two years, known as the Reformist Biennium, the government led by Manuel Azaña started many changes to modernize Spain. They stopped religious groups from controlling schools and began building many new schools. They also made some changes to land ownership. Catalonia was given more self-rule, with its own parliament and president.

Later, Azaña lost support, and President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora asked him to resign in September 1933. The next election in 1933 was won by the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA). However, the President did not ask CEDA's leader, Gil Robles, to form a government. Instead, he asked Alejandro Lerroux from the Radical Republican Party. CEDA was not given government positions for almost a year.

In October 1934, CEDA finally got three government jobs. This led to a major uprising by Socialists, who had been planning it for months. A general strike was called by the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) and the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE). This became a bloody rebellion. Armed rebels took over the entire province of Asturias. They attacked buildings and the University of Oviedo. In these areas, rebels declared a workers' revolution and stopped using regular money. The rebellion was stopped by the Spanish Navy and the Spanish Republican Army.

In 1935, after some problems and scandals, President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora called for new elections. The Popular Front won the 1936 general election by a small margin. After this, some right-wing groups sped up their plans for a military takeover.

On July 12, 1936, a leader of the opposition, José Calvo Sotelo, was killed. This event convinced many military officers to support the planned takeover. Three days later, on July 17, the revolt began with an army uprising in Spanish Morocco. It then spread to many cities in Spain. The military rebels wanted to take power quickly. But they faced strong resistance, as most major cities stayed loyal to the Republic. About half a million people died in the war that followed.

During the Spanish Civil War, there were three Republican governments. The first was led by José Giral. During his time, a revolution inspired by socialist and anarchist ideas began. The second government was led by Francisco Largo Caballero. The UGT and the National Confederation of Workers (CNT) were key groups in the social changes. The third government was led by Juan Negrín. He led the Republic until a military coup by Segismundo Casado ended the Republic's fight, leading to the Nationalists' victory.

The Republican government continued to exist in exile and had an embassy in Mexico City until 1976. After Spain became a democracy again, the government-in-exile officially ended the next year.

Contents

How the Republic Began (1931–1933)

On January 28, 1930, the military government of General Miguel Primo de Rivera ended. This brought together different groups who wanted a republic. These included conservatives, socialists, and Catalan nationalists. They signed the Pact of San Sebastián to work together to replace the monarchy with a republic. Many people did not want the King to return.

The local elections on April 12, 1931, were a big win for those who wanted a republic. Two days later, the Second Republic was declared, and King Alfonso XIII went into exile. A temporary government was formed under Niceto Alcalá-Zamora. In May 1931, some Catholic churches and buildings were set on fire in cities like Madrid and Sevilla.

The 1931 Constitution

In June 1931, a special assembly was chosen to write a new constitution. It became law in December.

The new constitution allowed freedom of speech and freedom of association. It gave women the right to vote in 1933 and allowed divorce. It also removed special legal status for Spanish nobles. The constitution also greatly reduced the power of the Roman Catholic Church. It put strict controls on Church property and stopped religious groups from teaching. Some people at the time felt this part of the constitution was very harsh on religion.

The law-making part of the government became a single group called the Congress of Deputies. The constitution also allowed the government to take control of public services, land, banks, and railways. It generally protected people's freedoms and rights.

The Republic's Constitution also changed Spain's national symbols. The Himno de Riego became the national anthem. The Tricolor flag, with red, yellow, and purple stripes, became the new flag. Under the new Constitution, all regions of Spain could have autonomy (self-rule). Catalonia (1932) and the Basque Country (1936) used this right. Galicia also tried, but the war stopped it. The constitution promised many freedoms, but it went against the strong beliefs of right-wing groups and the Catholic Church, which lost its schools and public money.

The 1931 Constitution was officially in effect from 1931 to 1939. But after the Spanish Civil War started in 1936, its power weakened. In many places, revolutionary groups took over instead of the Republic.

The Azaña Government and Reforms

After the new constitution was approved in December 1931, the government led by Manuel Azaña started many changes. They aimed to "modernize" the country.

In 1932, the Jesuits, who ran many good schools, were banned, and their property was taken by the government. Landowners also had some of their land taken. Catalonia was given self-rule, with its own local parliament and president. In 1932, some Catholic churches in big cities were again set on fire. There was also a workers' strike in Málaga. In 1933, a Catholic church in Zaragoza was burned down.

In 1933, all remaining religious groups had to pay taxes. They were also stopped from working in industry, trade, and education. This rule was enforced strictly, and there was also violence from mobs.

Political Changes and Uprisings (1933–1935)

The Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA) won the most votes in the 1933 elections. However, President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora did not ask CEDA's leader, Gil Robles, to form a government. Instead, he asked Alejandro Lerroux from the Radical Republican Party. CEDA, despite winning the most votes, was not given government jobs for almost a year. After much pressure, CEDA finally got three government positions.

The Left did not like CEDA joining the government, even though it was normal in a democracy. The Socialists started an uprising they had been planning. A general strike was called by the UGT and the PSOE. The Left Republicans believed the Republic should only follow their left-wing policies. Any change, even if democratic, was seen as a betrayal.

When three CEDA ministers joined the government on October 1, 1934, it led to a nationwide revolt. In Catalonia, a "Catalan State" was declared by leader Lluís Companys, but it lasted only ten hours. Other strikes did not last long, leaving the Asturian miners to fight alone. Miners in Asturias took over the capital, Oviedo, and killed some officials and religious leaders. Many religious buildings, including churches and part of the university, were burned. The miners also took over other towns and set up "revolutionary committees" to govern them. They declared a workers' revolution and stopped using regular money. This rebellion lasted two weeks until the army, led by General Eduardo López Ochoa, stopped it.

This rebellion showed that some Socialists also rejected the democratic system, similar to anarchists. A Spanish historian, Salvador de Madariaga, who supported Azaña, criticized the Left's role in the revolt. He said, "The uprising of 1934 is unforgivable. With the rebellion of 1934, the Spanish left lost even the shadow of moral authority to condemn the rebellion of 1936."

The stopping of land reforms and the failure of the Asturias miners' uprising made left-wing parties, especially the PSOE, more extreme. Francisco Largo Caballero became more popular, supporting a socialist revolution. At the same time, a corruption scandal weakened the Centrist government party. These events made the political differences between the right and left even stronger, which was clear in the 1936 elections.

The 1936 Elections

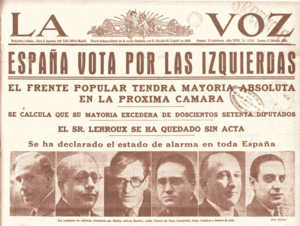

On January 7, 1936, new elections were called. Despite their differences, socialists, Communists, and left-wing Republicans from Catalonia and Madrid decided to work together as the Popular Front. The Popular Front won the election on February 16. They got 263 members of parliament, while the right-wing groups (like CEDA, Carlists, and Monarchists) got 156. Moderate center parties almost disappeared.

In the 36 hours after the election, 16 people were killed, and 39 were seriously hurt. Fifty churches and 70 right-wing political centers were attacked or burned. The right-wing groups had strongly believed they would win. Soon after the results were known, some monarchists asked Robles to lead a takeover, but he refused. He did ask the prime minister to declare a state of war. General Franco also suggested declaring martial law and calling out the army. This was not a coup attempt but more of a "police action," as Franco thought the situation could become violent. The prime minister resigned before a new government could be formed.

The Popular Front, which was good for winning elections, did not form a united government. Largo Caballero and other left-wing leaders were not ready to work with the Republicans, though they did support many of the proposed reforms. Manuel Azaña Díaz was asked to form a government. He soon replaced Zamora as president.

The right-wing groups reacted as if radical communists had taken control, even though the new government was moderate. They were shocked by the revolutionary crowds in the streets and the release of prisoners. Convinced that the left was no longer following the law and that their vision for Spain was in danger, the right-wing groups stopped trying to win through parliament. Instead, they began to plan how to overthrow the Republic.

This situation helped the Falange, a nationalist party led by José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the son of the former dictator. Even though it only got a small percentage of votes in the election, by July 1936, the Falange had 40,000 members.

The country quickly became very chaotic. Even the socialist Indalecio Prieto said in May 1936, "we have never seen so tragic a panorama or so great a collapse as in Spain at this moment. Abroad Spain is classified as insolvent. This is not the road to socialism or communism but to desperate anarchism without even the advantage of liberty."

Assassinations and the Start of the War

On July 12, 1936, Lieutenant José Castillo, a member of an anti-fascist military group, was shot by Falangist gunmen.

In response, a group of Guardia de Asalto police and other left-wing fighters, led by Civil Guard Fernando Condés, went to the house of right-wing opposition leader José Calvo Sotelo early on July 13. They arrested him, and he was later shot dead in a police truck. His body was left at a cemetery entrance. The killer was a socialist gunman, Luis Cuenca. Calvo Sotelo was a well-known monarchist who had been urging the army to step in and save the country from communism.

Many right-wing people blamed the government for Calvo Sotelo's assassination. They said the authorities did not investigate properly and even helped those involved. This event is often seen as the trigger for more political division. The Falange and other right-wing individuals were already planning a military takeover led by senior army officers.

When Castillo and Calvo Sotelo were buried on the same day in the same Madrid cemetery, fighting broke out in the streets. This led to four more deaths.

The killing of Calvo Sotelo, especially with police involvement, caused strong reactions among the government's opponents. Although generals were already planning an uprising, this event became a public reason for a coup. Historian Stanley G. Payne suggests that before these events, the idea of a military rebellion was weakening. But the murder of Sotelo turned the "limping conspiracy" into a revolt that could start a civil war. The fact that public order forces were involved and no action was taken against the attackers hurt public trust in the government. The murder of a parliamentary leader by state police was unheard of. This made important right-wing groups join the rebellion. Within hours of hearing about the murder, Francisco Franco, who had not been involved in the plans until then, decided to join the rebellion.

Three days later, on July 17, the coup d'état began as planned. An army uprising started in Spanish Morocco and then spread to several regions of Spain.

The main goal of the revolt was to end the chaos. Mola's plan for the new government was a "republican dictatorship," similar to Portugal's. It would be an authoritarian government, not a totalitarian fascist one. The first government would be a military "Directory" to create a "strong and disciplined state." General Sanjurjo would lead this new government. The 1931 Constitution would be paused, and a new parliament would be chosen. Some liberal ideas, like the separation of church and state, would remain.

Franco's move was meant to take power quickly. But his army uprising faced strong resistance. Many parts of Spain, including most major cities, stayed loyal to the Republic. The leaders of the coup did not give up. Instead, they started a slow and determined war against the Republican government in Madrid.

As a result, about half a million people died in the war that followed.

The Spanish Civil War

On July 17, 1936, General Franco led the Spanish Army of Africa from Morocco to attack mainland Spain. Another force from the north, led by General Emilio Mola, moved south from Navarre. Military units also mobilized elsewhere to take over government buildings. Soon, Franco's army controlled much of the south and west. After taking control of an area, the rebels carried out violent actions to secure Franco's future rule.

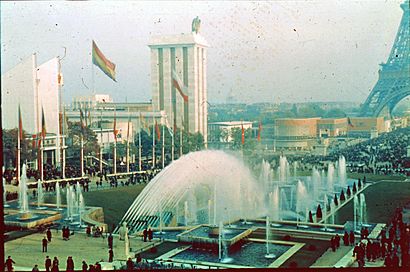

Both sides received military help from other countries. However, the help that Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, and Portugal gave the rebels was much greater and more effective. The Republic received help from the USSR, Mexico, and volunteers from the International Brigades. While the Axis powers strongly supported General Franco, the governments of France, Britain, and other European countries did not help the Republican forces. The Non-Intervention Committee tried to stay neutral, but this ended up helping the future Axis Powers.

The Siege of the Alcázar at Toledo early in the war was a turning point, with the rebels winning after a long siege. The Republicans managed to hold Madrid, despite a Nationalist attack in November 1936. They also stopped later attacks on the capital at Jarama and Guadalajara in 1937. However, the rebels slowly took more territory, cutting off Madrid and moving into the east. The north, including the Basque country, fell in late 1937. The Aragon front collapsed soon after. The bombing of Guernica was one of the most famous events of the war. It inspired Picasso's painting and was used by the German air force to test new tactics. The Battle of the Ebro in July–November 1938 was the Republicans' last big effort to change the war's outcome. When it failed and Barcelona fell to the rebels in early 1939, it was clear the war was over. The remaining Republican areas collapsed, and Madrid fell in March 1939.

Economy of the Second Spanish Republic

The economy of the Second Spanish Republic was mostly based on farming. Many historians describe Spain at this time as a "backward nation." The main industries were in the Basque region and Catalonia. The Basque region had good iron ore. This caused economic problems because the industrial centers were far from the natural resources. This meant high transportation costs due to Spain's mountains. Spain also did not export many goods, and most manufacturing was for its own people. High poverty levels made many Spaniards open to extreme political parties that promised solutions.

See also

- Spanish Republican Armed Forces

- Spanish Republican government in exile

- Flag of the Second Spanish Republic

- Coat of Arms of the Second Spanish Republic

- Order of the Spanish Republic

- LAPE (Líneas Aéreas Postales Españolas), the Spanish Republican Airline

- Catholicism in the Second Spanish Republic

- Sanjurjada

- Electoral Carlism (Second Republic)

In Spanish: Segunda República española para niños

In Spanish: Segunda República española para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |