Bombing of Guernica facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Rügen |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish Civil War | |

Ruins of Guernica (1937) |

|

| Type | Aerial bombing |

| Location | Guernica, Basque Country, Spain |

| Planned by | National Defense Junta |

| Objective | |

| Date | 26 April 1937 16:30 – 19:30 (CET) |

| Executed by | |

| Casualties | ~150–1,650 (estimates vary) killed |

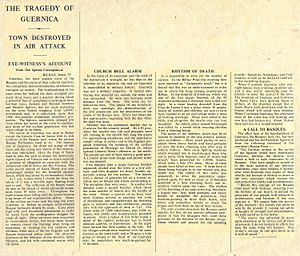

On April 26, 1937, the Basque town of Guernica (called Gernika in Basque) was bombed from the air during the Spanish Civil War. This attack was ordered by Francisco Franco's rebel Nationalist side. It was carried out by their allies: the Nazi German Luftwaffe's Condor Legion and the Fascist Italian Aviazione Legionaria. The secret name for this mission was "Operation Rügen".

Guernica was important because it was a communication center for the Republican forces, right behind the front lines. The bombing aimed to destroy bridges and roads there. This attack helped Franco's forces capture Bilbao and win the war in northern Spain.

The bombing became very controversial because it involved bombing civilians. Some historians call it a war crime, while others argue it was a fair military attack. It was one of the first air bombings to get worldwide attention. At the time, under international laws, Guernica was considered a valid military target.

The number of people killed is still debated. The Basque government first reported 1,654 deaths. Later, local historians found 126 victims, which they then changed to 153. A British source used by the USAF Air War College says 400 civilians died. Soviet records from May 1, 1937, claim 800 deaths. However, this number might not include people who died later from their injuries or whose bodies were found in the rubble.

The bombing is the main subject of the famous anti-war painting Guernica by Pablo Picasso. The Spanish Republic asked him to create this painting. Many other artists were also shocked and inspired by the bombing.

Contents

Guernica: A Special Town

Guernica (officially Gernika-Lumo) is in the Basque province of Biscay, about 30 kilometers east of Bilbao. It has always been very important to the Basque people. Its famous Gernikako Arbola (meaning "the tree of Gernika" in Basque) is an oak tree. This tree symbolizes freedom for the people of Biscay and all Basques. Guernica was seen as a key part of the Basque identity. It was also known as the spiritual capital of the Basque people.

At the time of the bombing, Guernica had about 7,000 people. The battlefront was only 30 kilometers away.

Military Situation in the War

Nationalist troops, led by Generalísimo Francisco Franco, were taking over land controlled by the Republican Government. The Basque Government, a local group of Basque nationalists, tried to protect their region with their own Basque Army.

When the bombing happened, Guernica was a very important spot for the Republican forces. It stood between the Nationalists and their goal of capturing Bilbao. Taking Bilbao was seen as key to ending the war in northern Spain. Guernica was also the escape route for Republicans from the northeast of Biscay.

Before the Condor Legion's attack, Guernica had not been directly involved in the fighting. However, Republican forces were in the area. There were 23 battalions of Basque army troops east of Guernica. The town itself also had two Basque army battalions. Guernica had no air defenses, and its leaders thought no air support would come because the Republican Air Force had lost many planes recently.

Market Day in Guernica

Monday, April 26, was market day in Guernica. This meant more than 10,000 people were in the town. Market days usually brought people from nearby areas to Guernica to buy and sell goods. Local farmers would bring their crops to the main square, where the market was held.

There is some debate among historians about whether a market was actually held that Monday. Before the bombing, the Basque government had ordered a stop to markets to prevent roads from getting too crowded. They also limited large gatherings. However, most historians agree that Monday "...would have been a market day."

The Air Raid on Guernica

The Condor Legion was a group of German air force units fighting for the Nationalists. The order to bomb Guernica came from the Spanish Nationalist Command to the Condor Legion's leader, Oberstleutnant Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen.

Why Guernica Was Targeted

Records from the mission's planner and commander, made public in the 1970s, show that the attack on Guernica was part of a larger Nationalist plan. It was also meant to help Franco's troops already in the area.

Richthofen chose Guernica for several reasons. It had several army groups and three weapons factories. It was also close to the front lines. A nearby bridge connected to the main Basque defense position, which defenders might use to retreat. Richthofen's main goal was to block a key road junction near the front. This would stop Basque troop movements and allow General Mola's forces to break through and surround the enemy. Since precise bombing was not possible with the technology back then, the only way to hit the targets was to bomb a large area.

Richthofen understood how important the town was for the advance on Bilbao and for stopping Republican retreats. He ordered an attack on the roads and bridge in the Renteria area. Destroying the bridge was the main goal. This was because the bombing was meant to work with Nationalist troop movements against Republicans near Marquina. Other goals were to limit Republican traffic and equipment movement. They also wanted to prevent bridge repairs by creating rubble around it.

On March 22, 1937, Franco began his plan. General Emilio Mola would start the fight against the north (including Asturias, Santander, and Biscay). All Nationalist equipment was sent north to support Mola. The main reason to attack the north first was the belief that a quick victory could be won there. Mola wanted a fast fight. He told the Basque people that if they surrendered, he would spare their lives and homes. On March 31, Mola's threat became real, and fighting began in Durango.

The Condor Legion convinced Franco to send troops north, led by General Emilio Mola. On March 31, 1937, Mola attacked the province of Biscay, which included the bombing of Durango by the Condor Legion. Republicans fought hard against the German troops but were eventually pushed back. Many refugees fled to Guernica for safety. On April 25, Mola warned Franco that he planned a strong attack on Guernica.

To achieve these goals, 24 bombers were assigned to the mission. These included two Heinkel He 111s, one Dornier Do 17, eighteen Ju 52 Behelfsbomber, and three Italian Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 planes. They carried medium and light explosive bombs, and incendiary (fire-starting) bombs. The total weight of bombs was 22 tons. A follow-up attack with Messerschmitt Bf 109 planes was also planned for the next day.

The Bombing Begins

The first group of planes arrived over Guernica around 4:30 PM. A Dornier Do 17 dropped about twelve 50 kg bombs.

The three Italian SM.79s took off from Soria at 3:30 PM. Their orders were to "bomb the road and bridge east of Guernica, to block the enemy retreat." Their orders specifically said not to bomb the town itself. During a single 60-second pass over the town, the SM.79s dropped thirty-six 50 kg light explosive bombs. Historian César Vidal says that at this point, the damage to the town was "relatively limited... confined to a few buildings."

The next three waves of the first attack happened, ending around 6:00 PM. The third wave had a Heinkel He 111 with five Italian Regia Aeronautica Fiat CR.32 fighter planes. The fourth and fifth waves were carried out by German twin-engine planes. Vidal noted that if the attacks had stopped then, it would have been a huge and unfair punishment for a town that had been far from the war. However, the biggest part of the operation was still to come.

More Attacks

Earlier that day, around noon, the Junkers Ju 52s of the Condor Legion had flown a mission around Gerrikaraiz. After that, they landed to reload bombs and then took off again for the main raid on Guernica. The attack would come from the north, from the Bay of Biscay, and follow the Urdaibai estuary.

The 1st and 2nd Squadrons of the Condor Legion took off around 4:30 PM. The 3rd Squadron took off from Burgos a few minutes later. They were protected by a squadron of Fiat fighters and Messerschmitt Bf 109Bs. In total, twenty-nine planes were involved.

From 6:30 PM to 6:45 PM, each of the three bomber squadrons attacked in a formation of three Ju 52s side-by-side. This created a bombing front of about 150 meters. At the same time, and for about 15 minutes after the bombing, the Bf 109Bs and Heinkel He 51 biplanes fired machine guns at the roads leading out of town. This added to the number of civilian casualties.

What Happened After

The bombing broke the will of the city's defenders to fight. This allowed the rebel Nationalists to take over the town easily. The rebels faced little resistance and took full control of Guernica by April 29.

The attacks destroyed most of Guernica. Three-quarters of the city's buildings were completely ruined, and most others were damaged. However, some important places were spared, like the weapons factories and the Assembly House Casa de Juntas and the Gernikako Arbola (the famous oak tree).

The bombing created a lot of rubble and confusion. This made it very hard for Republican forces to move around.

How Many People Died?

The number of civilians killed is now thought to be between 170 and 300 people. For many years, until the 1980s, it was believed that over 1,700 people had died. However, these numbers are now known to have been too high. Historians now agree that fewer than 300 people died.

One early study estimated 126 victims, later changed to 153. These numbers roughly match the town's surviving death records. However, they do not include the 592 deaths recorded in Bilbao's hospital. Other studies suggest around 250 to 300 deaths. These numbers are now widely accepted by historians and media.

After Nationalist forces took the town, they claimed that the other side had not tried to count the dead accurately. The Basque government, in the confusion after the attacks, reported 1,654 dead and 889 wounded. This roughly matched what British journalist George Steer reported. He estimated that 800 to 3,000 out of 5,000 people in Guernica had died. These higher figures were used by many people for decades.

The Nationalist government gave a false story, saying that Republicans had burned the town as they fled. They seemed to make no effort to find the true number of deaths. One Francoist newspaper even claimed in 1970 that only twelve people had died.

Damage to Buildings

The numbers for how much of the city was destroyed still vary. Some say 14% of buildings were destroyed by bombs. Others estimate that 74% of the buildings were destroyed, mainly because of fires that burned until the next day.

The Legacy of Guernica

The bombing quickly got international attention. People were horrified because it seemed civilians were intentionally targeted by air bombers. This was seen as a very wrong way to fight.

George Steer's reports about the terrible events in Guernica were greatly appreciated by the Basque people. He made their suffering known to the world. Later, the Basque authorities honored him by naming a street in Bilbao George Steer Kalea. They also put up a bronze statue with the words: "George Steer, journalist, who told the world the story about Guernica."

Even though Franco's government tried to hide the truth, the reports spread. This led to widespread international anger at the time. Some historians believe that the reactions to the bombing of Guernica helped shape the modern idea of human rights.

Picasso's Famous Painting

Guernica quickly became a worldwide symbol of how civilians suffer in war. It inspired Pablo Picasso to change one of his art projects into his famous painting, Guernica. The Spanish Republican Government had asked him to create a work for the Spanish pavilion at the Paris International Exposition. Picasso accepted, but he didn't feel inspired until he heard about the bombing of Guernica. Before this, Picasso didn't care much about politics. But once he heard the news, he changed his commissioned work to show the horror of the attack.

Picasso started the painting on May 11, 1937. It is a very large work, so he had to use a ladder and a long brush to reach all parts of the canvas. He spent over two months creating Guernica. He used only black and white paint to make it look like a powerful, truthful photograph.

The painting was shown at the Spanish Pavilion during the 1937 World's Fair in Paris. It showed how much the bombing affected people. The painting later became a symbol of Basque nationalism during Spain's move to democracy. Today, it is kept in the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. A copy of Picasso's Guernica made from fabric hangs on the wall of the United Nations building in New York City. It is at the entrance to the Security Council room, serving as a reminder of the terrible things that happen in war.

German Apology

After Germany was reunified in the 1990s, people began to feel regret and shame about the Condor Legion's actions and Germany's role in the bombing of Guernica. In 1997, on the 60th anniversary of Operation Rügen, the German President Roman Herzog wrote to survivors. He apologized on behalf of the German people and state for Germany's part in the Civil War. Herzog said he wanted to offer "a hand of friendship and reconciliation" from all German citizens. This feeling was later supported by members of the German Parliament. In 1998, they passed a law to remove the names of all former Legion members from German military bases.

70th Anniversary of the Bombing

On the 70th anniversary of the bombing, the president of the Basque Parliament met with politicians, Nobel Peace Prize winner Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, and leaders from cities like Hiroshima and Dresden. Several survivors from Guernica were also there. During the meeting, they showed pictures and videos of the bombing. They took time to remember the 250 people who died. They also read the Guernica Manifesto for Peace, asking that Guernica become a "World Capital for Peace."

2016 Film about Guernica

The 2016 film Guernica tells the story leading up to and including the bombing of Guernica. It also shows the people involved in reporting on the war.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Bombardeo de Guernica para niños

In Spanish: Bombardeo de Guernica para niños

- Condor Legion

- Aviazione Legionaria

- Bombing of Chongqing, 1938-1943

- Bombing of Wieluń

- Bombing of Tokyo

- Battle of Aleppo (2012–2016)

- Guernica (painting)

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |