George Steer facts for kids

George Lowther Steer (born 22 November 1909 – died 25 December 1944) was a journalist and writer from South Africa. He became famous as a war correspondent, reporting on conflicts before World War II. He wrote for The Times newspaper.

His reports helped people in Western countries learn about terrible acts committed during wars. He wrote about the Italians in Ethiopia and the Germans in Spain. His special report in 1937 about the bombing of Guernica inspired the famous artist Pablo Picasso to paint his anti-war masterpiece, Guernica. After World War II began, George Steer returned to Ethiopia. He helped in the fight to defeat the Italians and bring Emperor Hailie Selassie back to power.

Contents

Early Life and Education

George Steer was born in South Africa in 1909. His father managed a newspaper. George later moved to England to study. He went to Winchester College and Christ Church, Oxford, where he studied ancient Greek and Roman history and literature. He started his career as a journalist in South Africa. After that, he worked in London for the Yorkshire Post newspaper.

Reporting from War Zones

George Steer became well-known for reporting from dangerous war zones. He bravely shared what he saw with the world.

Reporting on the Ethiopian War

In 1935, Steer reported on the Italian invasion of Ethiopia for The Times. This war is also known as the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. He wrote that Italian forces used dangerous gases, like mustard gas. They also bombed Red Cross ambulances, even though they were clearly marked.

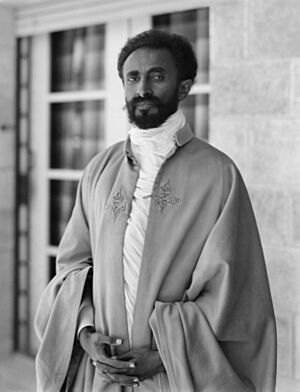

George Steer helped transport gas masks to Ethiopia. These masks offered some protection against the illegal use of poison gases. He became good friends with Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia. Later, the Emperor became the godfather to Steer's son. George Steer met and married his first wife in Ethiopia. This happened during difficult times, with fighting and looting outside the British Legation in Addis Ababa. Sadly, his wife and their first child died during childbirth in London a short time later.

Reporting on the Spanish Civil War

In 1937, George Steer was sent to report on the Spanish Civil War. His first reports from the Basque region described how British ships brought food to the hungry people of Bilbao. These ships managed to get past the blockade set up by the Nationalist forces. He also visited the front lines many times to report directly on the fighting.

He became very famous for his exclusive report on the bombing of Guernica. This terrible event happened on 26 April 1937. His message to London described German bombs. These bombs had German eagle symbols and the words Rheindorf 1936 on them. He also reported that the attackers used special bombs called thermite. These bombs created a huge firestorm in the town. High explosive bombs were used to damage wooden buildings, making them easier to burn.

Steer's reporting greatly inspired the artist Pablo Picasso. Picasso created his huge 1937 painting, Guernica, to show the horror of the attack. Steer's reports also warned Western governments. They showed how the Germans were planning to use terror bombing to scare civilians.

The Nationalist forces said Steer's reports were wrong. They claimed the damage was caused by the Republican forces themselves. However, an investigation by the League of Nations did not agree with either side's full story. Steer responded by giving details about the damage, like bomb craters. He also identified the German planes, such as Heinkel He 111 bombers, used in the attack. Although he didn't see the bombing happen, he arrived soon after. This allowed him to see the damage and talk to survivors. He was one of the last journalists to leave Bilbao as the Nationalists advanced. He then escaped to Santander.

Reporting on the Winter War

The Times newspaper stopped working with Steer because his reports were against Fascism. The newspaper's editor, Geoffrey Dawson, supported the Nationalists. Also, the newspaper generally tried to avoid conflict with Germany and the Nazis.

Steer returned to South Africa. In his book Judgment on German Africa, he wrote about Germany's attempts to take over its former African colonies. These included Cameroon, South West Africa (now Namibia), Tanganyika, and Togoland.

After World War II began, the Daily Telegraph sent Steer to Finland. He covered the Winter War, which started when the Soviet Union attacked Finland in November 1939. Steer saw how the Soviets bombed Finnish towns to scare the people, just like at Guernica. But this time, Western countries like Britain and France were eager to help Finland. They sent weapons, equipment, and volunteers. The war was short because the Soviet Union was much stronger. However, the Soviets had many more casualties than the Finns. A peace agreement was signed in March 1940, and Finland lost about 10% of its land to the Soviets.

Return to Ethiopia

When Italy declared war on Britain, plans were made to invade Ethiopia. The goal was to remove the Italian government and bring Emperor Haile Selassie back to power. Steer became an officer in the British Army's Intelligence Corps. His first job was to secretly take Selassie from London to Sudan.

He was then put in charge of a special unit. This unit used leaflets and loudspeakers to weaken the Italian forces. They played Italian operas and news from the war in Libya, where the British army was winning against the Italians. This campaign was very successful. Many Italian soldiers left their posts and became prisoners. Many Ethiopians also switched their support. The British and Ethiopian soldiers fought well. They entered Addis Ababa in April 1941, celebrating their victory over the Italians.

Personal Life

In May 1936, George Steer married Margarita Herrero, a French newspaper reporter. This happened while he was taking a break from his rescue work. Soon after, the Italian authorities forced him and other Europeans to leave Ethiopia because they had helped the Ethiopians. Sadly, Margarita Steer died during childbirth in London while George Steer was reporting on the Spanish Civil War. He later married Esme Barton.

In 2006, the town of Guernica honored George Steer. They unveiled a bronze statue of him and named a street after him. In 2010, Bilbao also named a street "George Steer Street." Steer's son and granddaughter attended the ceremony.

Military Service and Death

In June 1940, Steer joined the British Army. He led an Ethiopian propaganda unit when British troops fought the Italians in Ethiopia. After the Italians were defeated in 1941, Steer played an important role in helping Haile Selassie return to his throne.

Later, Steer was sent to India. He led a propaganda unit in Burma. This unit tried to lower the Japanese soldiers' spirits. They used loudspeakers to play speeches and sentimental music. Steer was promoted several times, becoming a Lieutenant, then Captain, Major, and finally, Lieutenant-colonel. He was part of the Special Operations Executive. His work was praised by General Slim, the local army commander, who wanted to expand the operation.

George Steer died in a car crash in Burma on 25 December 1944. He was driving a heavily loaded Army Jeep on his way to a Christmas party.

Books About George Steer

- Nicholas Rankin – Telegram from Guernica: The Extraordinary Life of George Steer, War Correspondent ISBN: 0-571-20563-1, 2003, Faber and Faber