William Slim, 1st Viscount Slim facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Viscount Slim

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 13th Governor-General of Australia | |

| In office 8 May 1953 – 2 February 1960 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Prime Minister | Robert Menzies |

| Preceded by | Sir William McKell |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Dunrossil |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Joseph Slim

6 August 1891 Bishopston, Bristol, England |

| Died | 14 December 1970 (aged 79) London, England |

| Resting place | Memorial plaque in St Paul's Cathedral |

| Spouse |

Aileen Robertson

(m. 1926) |

| Children | 2nd Viscount Slim Una Mary Slim |

| Alma mater | Staff College, Quetta |

| Nickname | "Uncle Bill" |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Branch/service | British Army British Indian Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1952 |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Unit |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

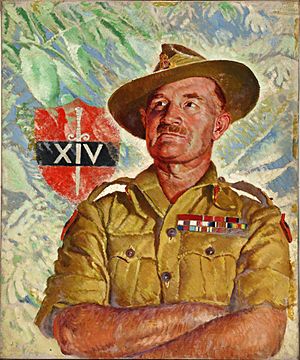

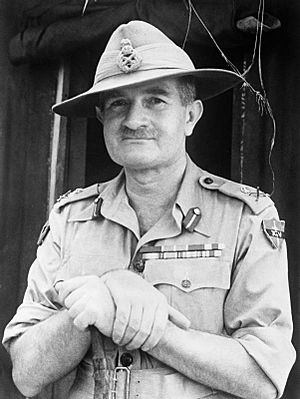

Field Marshal William Joseph Slim, also known as Bill Slim, was a very important British military leader. He was born on August 6, 1891, and passed away on December 14, 1970. He served in both the First World War and the Second World War. After his military career, he became the 13th Governor-General of Australia.

During the Second World War, he led the Fourteenth Army. This army was sometimes called the "forgotten army" because their fight in the Burma campaign was not always in the news. After the war, he became the first British officer from the Indian Army to be appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff, a very high military position. From 1953 to 1959, he served as Governor-General of Australia.

In the 1930s, Slim also wrote books and stories. He used the pen name Anthony Mills for his writing.

Contents

Early Life and Education

William Slim was born in Bristol, England. His father was John Slim, and his mother was Charlotte Tucker. He went to St Bonaventure's Primary School in Bristol. Later, he moved to Birmingham and attended St Philip's Grammar School and King Edward's School, Birmingham.

After school, his family faced financial difficulties. His father's business failed, so only his older brother could go to university. Between 1910 and 1914, William Slim worked as a primary school teacher. He also worked as a clerk for a company that made metal tubes.

Service in the First World War

Even though he didn't go to university, Slim joined the Birmingham University Officers' Training Corps in 1912. This allowed him to become a temporary officer in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment when the First World War began on August 22, 1914.

He was seriously injured during the Gallipoli Campaign. After recovering, he joined the West India Regiment. In October 1916, he returned to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in Mesopotamia. He was wounded a second time in 1917. For his brave actions in Mesopotamia, he received the Military Cross on February 7, 1918.

He was then sent to India to recover. On May 22, 1919, he officially joined the Indian Army.

Between the World Wars

In 1921, Slim became a battalion adjutant with the 6th Gurkha Rifles. This meant he helped manage the daily operations of the battalion.

On January 1, 1926, he married Aileen Robertson. They had one son and one daughter. Later that year, Slim attended the Staff College, Quetta, a special school for military officers. His good performance there led him to work at Army Headquarters in Delhi. He then taught at the Staff College, Camberley, in England from 1934 to 1937. During this time, he wrote novels and stories under the name Anthony Mills to earn extra money and follow his passion for writing.

In 1937, he attended the Imperial Defence College. The next year, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He took command of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Gurkha Rifles. In 1939, he became a temporary brigadier. He was then appointed head of the Senior Officers' School, Belgaum in India.

Second World War Leadership

East African Campaign

When the Second World War started, Slim was given command of the 10th Indian Infantry Brigade. This unit was part of the 5th Indian Infantry Division. They were sent to Sudan to fight in the East African campaign. Their goal was to free Ethiopia from Italian control. Slim was wounded again on January 21, 1941, during a battle in Eritrea.

Middle East Operations

While recovering from his injuries, Slim worked at the army headquarters in Delhi. He helped plan for possible operations in Iraq. In May 1941, he was appointed chief staff officer for operations in Iraq. Soon after, he was promoted to major-general. He led the Indian 10th Infantry Division in several campaigns. These included the Anglo-Iraqi War, the Syria-Lebanon campaign, and the invasion of Persia. His actions were mentioned in official reports twice in 1941.

The Burma Campaign

In March 1942, Slim took command of Burma Corps. This group was fighting the Japanese in Burma. The Japanese were very strong and mobile, forcing Slim's corps to retreat to India. On October 28, 1942, Slim received the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for his service.

Slim then took over XV Corps. He had some disagreements with his superior, Noel Irwin. Eventually, Irwin was removed, and Slim was promoted to lead the new Fourteenth Army. This army was made up of several different corps. On January 14, 1943, Slim was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his actions in the Middle East.

Slim quickly began training his new army for jungle warfare. He believed that being able to move off-road was most important. They used mules and air transport instead of heavy vehicles. He taught his soldiers to form defensive "boxes" if surrounded. These boxes would be supplied by air. He also encouraged night training to help his soldiers overcome their fear of the jungle. He wanted them to believe they were just as good as the Japanese in jungle fighting.

The Chin Hills were a natural barrier into Burma. Slim wanted to go around them by sea, but there weren't enough ships. So, he had to plan an overland advance. The Japanese also increased their forces in Burma, making the advance even harder.

Slim clashed with Brigadier Orde Wingate, who took some of Slim's best units for his special raiding group called the Chindits. Slim thought the Japanese would be much tougher than Wingate's previous enemies. However, Slim did support helping the local hill tribes of Burma. These groups, like the Kachins and Karens, had remained loyal to the British. They were willing to fight the Japanese who had treated them badly.

In January 1944, the Japanese launched a counter-attack in the Arakan Peninsula. Several Indian divisions were surrounded. Their defense relied on an "Admin Box" made up of support staff like drivers and cooks. They were supplied by air, which showed the Japanese that cutting supply lines on the ground was not enough. The Japanese could stop the British advance but couldn't defeat the surrounded forces.

In early 1944, the Japanese planned to invade India. They hoped the British Fourteenth Army would collapse. They also believed that Subhas Chandra Bose and his Indian National Army would inspire Indian soldiers to rebel. Slim knew the Japanese were coming from secret intelligence. He decided to fight a defensive battle first. He believed British tanks, supplies, and air power would help him win.

The Japanese advanced quickly, creating a tense situation. Slim airlifted two experienced divisions directly into battle. Fierce defensive battles took place at Imphal and Kohima. The RAF and USAAF kept the troops supplied by air. Slim ordered his men to hold their ground and not retreat. He promised them supplies would come by air. The Battle of Kohima was incredibly fierce, but the British forces held on.

By July 1944, the Japanese invasion had failed. Of the 150,000 Japanese soldiers who invaded India, most were dead by July. Many died from hunger and disease. Slim had inflicted the largest defeat on the Japanese up to that point in the war. The Indian Army remained loyal and fought bravely.

Unlike the Japanese, who often left their wounded, Slim made sure his wounded soldiers received excellent medical care. They were flown to hospitals in India. He knew that soldiers would fight better if they knew they would be cared for. On August 8, 1944, Slim was promoted to lieutenant general. He was also made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) on September 28, 1944. In December 1944, Slim and three of his corps commanders were knighted in a ceremony. By the end of 1944, most of the British Fourteenth Army's soldiers were from India or Britain's African colonies, not Britain itself. Slim had to be a diplomat to keep all these different groups working together.

In 1945, Slim launched an attack into Burma. His supply lines were very long, stretching through hundreds of miles of jungle. After the battles of Kohima and Imphal, Slim realized the Japanese had poor supplies. He also knew Japanese soldiers often fought to the death. So, he decided it was better to go around Japanese positions and let them starve, rather than fight them directly. Slim had fewer men than the Japanese, but he believed his army's better mobility and supplies would win. He wanted to save his soldiers' lives as much as possible.

Slim had a great relationship with his officers and soldiers. He trusted them to make good decisions without always asking him. This helped his army advance quickly.

He used elephants, led by a famous elephant named Bandoola, to build bridges and help refugees. Slim focused on keeping his armies supplied. The Chindwin River was crossed using the longest Bailey bridge in the world at that time. To trick the Japanese, Slim ordered Chinese forces in northern Burma to attack. This made the Japanese think the main goal was to open the Burma Road to China.

Slim began his main advance by sending two corps towards Mandalay. He then changed his plan when he learned the Japanese were defending Mandalay from the Irrawaddy River. Slim had one corps cross the Irrawaddy south of Mandalay at Meiktila. Another corps pretended to attack Mandalay from the north to distract the Japanese. The Irrawaddy River is very wide and fast-flowing, making it a strong natural defense. However, Slim used tanks and artillery with his infantry to create overwhelming firepower. In March 1945, after crossing the Irrawaddy, Meiktila was captured. Then, Mandalay, Burma's second-largest city, fell on March 20, 1945.

The Japanese in Mandalay fought fiercely in the city, destroying much of it. Slim's plan was very clever. Capturing Meiktila left most of Japan's troops in Burma without supplies. The Allies reached the open plains of central Burma. They broke up Japanese attacks and kept the upper hand. Air support was crucial, with planes supplying troops and helping in battles.

Local Burmese people also rose up against the Japanese. The Japanese faced attacks from behind their own lines. As Slim advanced, he found terrible evidence of Japanese cruelty, like villagers tied to trees and killed. Towards the end of the campaign, the army rushed south to capture Rangoon before the monsoon season. Capturing the port was essential for supplies. Rangoon was taken by a combined attack from land, air (paratroopers), and sea. Local groups, like the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League led by Aung San, also helped.

As the Burma campaign ended, Slim was told he wouldn't lead the army in the planned invasion of Malaya. He was offered a different command, but he refused, saying he would rather retire. When his troops heard this, they were upset. High-ranking officers intervened, and on July 1, 1945, Slim was promoted to general. He was then appointed commander of all Allied Land Forces in Southeast Asia. However, by the time he took the job, the war had ended.

Connecting with His Troops

Slim had an excellent relationship with his soldiers. They called themselves the "Forgotten Army". In his book, Defeat into Victory, he wrote about how many of his soldiers got malaria because they didn't take their medicine. Slim didn't blame the doctors. He put the responsibility on his officers. He said, "More than half the battle against disease is fought not by the doctors, but by the regimental officers." After he removed some officers for high malaria rates, others took it seriously. The malaria rate dropped greatly, making his army much stronger. This change helped them defeat the Japanese in Burma.

After the War

Leaving and Returning to the Army

At the end of 1945, Slim returned to the UK. On January 1, 1946, he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE). He became the head of the Imperial Defence College. After two years, he retired from the army on May 11, 1948. He was asked to lead the armies of newly independent India and Pakistan, but he declined. Instead, he became Deputy Chairman of the Railway Executive.

However, in November 1948, the British Prime Minister asked Slim to return to the army. In January 1949, he was brought back as a field marshal. He became the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS). This made him the first officer from the Indian Army to hold this very important position.

On January 2, 1950, he was promoted to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB). He also received the highest rank of the Legion of Merit from the United States. He left his position as Chief of the Imperial General Staff on November 1, 1952.

Governor-General of Australia

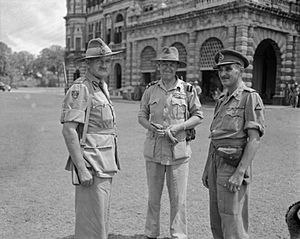

On December 10, 1952, Slim was appointed Governor-General of Australia. This is a representative of the British monarch in Australia. He took up this role on May 8, 1953. He was a popular choice because he was a war hero who had fought alongside Australians. In 1954, he welcomed Queen Elizabeth II on her first visit to Australia as reigning monarch. For his service during the Queen's tour, he received another honor on April 27, 1954.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1959, Slim retired and returned to Britain. He published his memories, including Defeat into Victory, which is still in print today. In this book, he openly discussed his mistakes and what he learned. On April 24, 1959, he was made a Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter. On July 15, 1960, he was given the title "Viscount Slim".

After his military career, he worked on the boards of large UK companies. On June 18, 1964, he was appointed Constable and Governor of Windsor Castle. He passed away in London on December 14, 1970, at the age of 79. He had a full military funeral.

Things Named After Him

- William Slim Drive in Canberra, Australia, was named after him until 2021.

- The Slim Officers' Mess at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst is named in his honor. His son opened it in August 2004.

- On September 7, 2008, a plaque was put up in Slim's memory at the Bristol Cenotaph in his hometown.

- Viscount Slim Avenue in Whyalla, South Australia, is named after him.

- The Slim Building at Cranfield University Shrivenham Campus is named after him.

- The Slim School in the Cameron Highlands, Malaya, was a secondary school named after him.

Remembering a Great Leader

Slim's book, Defeat into Victory, is highly recommended for its honest look at his experiences in the Burma campaign.

The strong bond Slim created within the Fourteenth Army continued after the war. He helped start and became the first President of the Burma Star Association, a group for veterans of the Burma campaign.

A statue of Slim stands on Whitehall in London, outside the Ministry of Defence. Queen Elizabeth II unveiled it in 1990. It is one of three statues of British Second World War military leaders.

Slim's personal papers were collected by his biographer, Ronald Lewin. They are now kept at the Churchill Archives Centre. Lewin's book about Slim, Slim: The Standardbearer, won a literary award in 1977.

Awards and Honors

| Knight of the Order of the Garter (KG) | 1959 | |

| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) | 1950 | |

| Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) | 1944 | |

| Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) | 1944 | |

| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG) | 1952 | |

| Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO) | 1954 | |

| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE) | 1946 | |

| Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) | 1942 | |

| Knight of the Order of St John (KStJ) | 1953 | |

| Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) | 1943 | |

| Military Cross (MC) | 1918 | |

| Chief Commander of the Legion of Merit | (United States) |