Orde Wingate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Orde Wingate

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 26 February 1903 Nainital, United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, British India (now in Uttarakhand, India) |

| Died | 24 March 1944 (aged 41) Near Bishnupur, Manipur State, British India (now in Manipur, India) |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ |

British Army |

| Years of service | 1921–1944 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Service number | 27013 |

| Unit | Royal Artillery |

| Commands held | Chindits (1942–44) Gideon Force (1940–41) |

| Battles/wars | 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine Second World War |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Order & Two Bars Mentioned in Despatches (2) You must specify issue= and startpage= when using . Available parameters: {{LondonGazette

|issue=

|date=

|startpage=

|endpage=

|title=

|supp=

|city=

|accessdate=

}}MacGregor Medal |

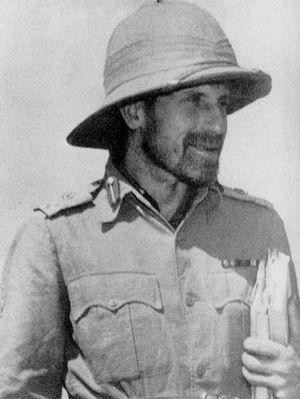

Major General Orde Charles Wingate (born 26 February 1903 – died 24 March 1944) was a senior officer in the British Army. He is best known for creating the Chindits, special forces units that operated deep behind enemy lines. These missions took place in Japanese-held territory during the Burma Campaign of the Second World War.

Wingate was a strong believer in new and surprising military tactics. When he was sent to Mandatory Palestine, he supported Zionism, which is the movement for a Jewish homeland. He helped set up a special unit of British and Jewish soldiers to fight against rebels.

With the support of his commander, Archibald Wavell, Wingate was given more freedom to use his ideas during the Second World War. He formed special military units in Abyssinia and Burma.

At a time when Britain needed a boost in spirits, Wingate caught the eye of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Wingate had a bold and independent way of thinking about war. He was given resources to plan a large military operation.

Wingate died in a plane crash in March 1944. The Chindit soldiers faced many challenges, especially from diseases. This led to a lot of debate about Wingate's methods. He believed that a strong mental attitude could help soldiers resist illness. However, medical officers thought his methods were not suitable for a tropical environment.

Contents

Early Life and Schooling

Wingate was born on 26 February 1903 in Nainital, India. He was the oldest of three sons in a military family. His father, Colonel George Wingate, was a devoted member of the Plymouth Brethren, a Christian group.

Most of Wingate's childhood was spent in England. For his first 12 years, he mostly spent time with his brothers and sisters. The seven Wingate children received a Christian education. They spent time each day studying and memorizing parts of the Bible.

In 1916, his family moved to Godalming. Wingate attended Charterhouse as a day student. He did not live at the school or take part in all its activities. Instead, his parents kept him busy at home. They encouraged their children to work on challenging projects. This helped them think for themselves and be independent.

Joining the Army

After four years, Wingate left Charterhouse. In 1921, he was accepted into the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. This was the training school for officers in the Royal Artillery.

New students at the academy faced a tough tradition called "running." This involved being stripped and forced to run past older students. The older students would hit them with knotted towels. At the end, the new student was thrown into icy water.

When it was Wingate's turn, he was accused of returning a horse too late. He walked up to the first senior student and dared him to strike. The senior refused. Wingate did the same to each senior, and they all refused. He then walked to the cistern and dived into the cold water himself.

In 1923, Wingate became an officer in the Royal Artillery. He was sent to the 5th Medium Brigade at Larkhill. During this time, he enjoyed horse riding very much. He became known for his skill in races and fox hunting. He was especially good at finding places to cross rivers, which earned him the nickname "Otter."

He was promoted to lieutenant on 29 August 1925. In 1926, because of his riding skills, Wingate was sent to the Military School of Equitation. He did very well there, even though he often challenged his instructors. This showed his rebellious nature.

Service in Sudan (1928–1933)

Wingate's father's cousin, Sir Reginald Wingate, was a retired general. He had been governor-general of the Sudan. He greatly influenced Wingate's career. He made Wingate interested in the Middle East and the Arabic language.

Wingate took an Arabic course in London and did very well. In June 1927, he got six months' leave to go on an expedition in Sudan. He traveled by bicycle through Europe before taking a boat to Egypt and then on to Khartoum.

In April 1928, Wingate joined the Sudan Defence Force (SDF). He was sent to an area near the borders of Ethiopia. The SDF patrolled there to stop illegal trading. Wingate changed their methods from regular patrols to surprise attacks.

In March 1930, Wingate was given command of 300 soldiers. He was happiest when he was out in the field with his unit. However, when he was at headquarters in Khartoum, he often argued with other officers. He was promoted to captain in the regular army on 16 April 1930.

At the end of his time in Sudan, Wingate went on a short trip into the Libyan desert. He wanted to look for a lost army mentioned by the ancient writer Herodotus. He also searched for a lost oasis. The expedition did not find the oasis. But Wingate saw it as a chance to test his strength and leadership skills in a very difficult environment. He finished his service in Sudan on 2 April 1933.

Return to the UK (1933–1936)

When Wingate returned to the UK in 1933, he was sent to Bulford. He helped retrain British artillery units as they were becoming mechanized. On his boat trip from Egypt, he met Lorna Moncrieff Patterson, who was 16. They got married two years later, on 24 January 1935.

From January 1935, Wingate worked with the Territorial Army. He was an adjutant for a Royal Artillery unit. He was promoted to captain on 16 May 1936.

Palestine and the Special Night Squads

In September 1936, Wingate was sent to Mandatory Palestine as an intelligence officer. From the moment he arrived, he believed that creating a Jewish State in Palestine was a religious duty. He quickly became a strong ally of Jewish political leaders. At that time, Palestinian Arab rebels were attacking British officials and Jewish communities.

Wingate became very involved with Zionist leaders. He became a passionate supporter of Zionism. He often returned to Kibbutz En Harod. He felt a connection to the biblical judge Gideon, who fought in that area. Wingate used it as his military base.

He came up with the idea of forming small attack units. These units would be made of British-led Jewish commandos. They would use grenades and light weapons to fight the Arab revolt. Wingate took his idea directly to Wavell, who was the commander of British forces in Palestine.

After Wavell approved, Wingate convinced the Jewish Agency and the leaders of Haganah, the Jewish armed group. In June 1938, the new British commander, General Haining, allowed the creation of the Special Night Squads (SNSs). These were armed groups of British and Haganah volunteers. The Jewish Agency helped pay for the Haganah members.

Wingate trained, commanded, and went with them on their patrols. The units often ambushed Arab rebels who attacked oil pipelines. They also raided villages that the attackers used as bases. In these raids, Wingate's men sometimes used harsh methods against the villagers. This was criticized by both Zionist leaders and Wingate's British superiors.

The tactics proved effective in stopping the uprising. Wingate was awarded the DSO in 1938 for his actions. However, his strong involvement with the Zionist cause and speaking publicly about a Jewish state led his superiors to remove him from command. They felt he was too involved in politics to be an intelligence officer there. In May 1939, he was transferred back to Britain. Wingate became a hero to the Yishuv (the Jewish Community). Leaders like Moshe Dayan trained under him and said Wingate "taught us everything we know."

Ethiopia and Gideon Force

When the Second World War began, Wingate was commanding an anti-aircraft unit in Britain. He repeatedly suggested creating a Jewish army in Palestine. His friend Wavell, who was commander-in-chief in the Middle East, invited him to Sudan. He wanted Wingate to start operations against Italian forces occupying Ethiopia.

Wingate created Gideon Force under William Platt, the British commander in Sudan. This was a Special Operations Executive (SOE) force. It was made up of British, Sudanese, and Ethiopian soldiers.

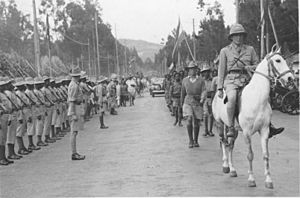

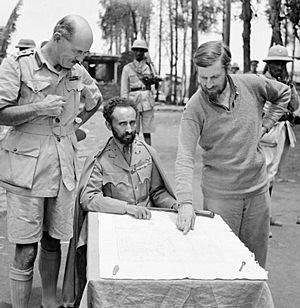

Gideon Force was named after the biblical judge Gideon. He defeated a large army with a small group of men. Wingate invited some veterans from the Haganah SNS to join him. With the support of Ethiopia's Emperor Haile Selassie, the group began operating in February 1941. The Italians had occupied Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941. Their rule was harsh, causing much suffering. Many Ethiopians were happy to help Gideon Force.

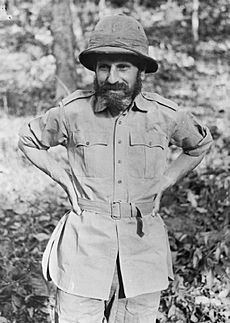

Wingate was temporarily promoted to lieutenant colonel and put in command. He again insisted on leading his troops from the front. He went with them in the fight to take back Abyssinia. Gideon Force attacked Italian forts and supply lines with the help of local resistance fighters. Meanwhile, regular army units fought the main Italian army. A small force of about 1,700 men accepted the surrender of about 20,000 Italians.

At the end of the fighting, Wingate and Gideon Force met up with Lt. Gen. Alan Cunningham's force. They had advanced from Kenya in the south. Wingate and his men accompanied the emperor when he returned to Addis Ababa in May. Wingate was recognized for his bravery in April 1941 and received another award (a bar to his DSO) in December.

After the East African Campaign ended on 4 June 1941, Wingate was removed from command of Gideon Force. His rank was reduced to major. During the campaign, he was upset that British authorities ignored his requests for awards for his men. They also made it hard for him to get their back pay. He went to Cairo and wrote a report that was very critical of his commanders and other officials. He was also angry that his efforts had not been praised. He was worried about British attempts to limit Ethiopian freedom.

Wingate got malaria soon after this. He saw a local doctor instead of army medical staff. He was afraid the illness would give his critics more reasons to undermine him. The doctor gave him a lot of a medicine that could cause depression if taken in high doses. Wingate was already feeling down about the official response to his command in Abyssinia.

A shortened version of his report was sent to Winston Churchill. Churchill's political supporters in London helped with this. Secretary of State for India Leo Amery asked Wavell if Wingate could be used in the Far East. Wingate was not happy with his new posting, but he left Britain for Rangoon on 27 February 1942.

Burma Campaigns

The First Chindit Mission

When Wingate arrived in the Far East in March 1942, General Wavell made him a colonel again. He was ordered to organize guerrilla units to fight behind Japanese lines. However, the Allied defenses in Burma quickly collapsed. Wingate flew back to India in April. There, he began to promote his ideas for special jungle units that could operate far behind enemy lines.

Wavell was interested in Wingate's ideas. He gave him the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. Wingate used this to create his jungle long-range penetration unit. This unit was eventually called the Chindits. The name came from a Burmese mythical lion called the chinthe.

By August 1942, Wingate had set up a training center in India. He tried to make the men tougher by having them camp in the Indian jungle during the rainy season. This caused many soldiers to get sick. In one battalion, 70 percent of the men were absent due to illness. A Gurkha battalion went from 750 men to 500. Many men were replaced in September 1942.

Wingate did not make many friends among other officers. He was very direct and had some unusual habits. He would eat raw onions because he thought they were healthy. He would also scrub himself with a rubber brush instead of bathing. Wavell's support protected him from too much criticism. Wingate was known for his outstanding courage and leadership in battle.

The first Chindit operation in 1943 was supposed to be part of a larger army plan. But the army's attack into Burma was canceled. Wingate then convinced Wavell to let him go into Burma anyway. He argued it was important to disrupt any Japanese attack and to test his long-range jungle operations. Wavell agreed to Operation Longcloth.

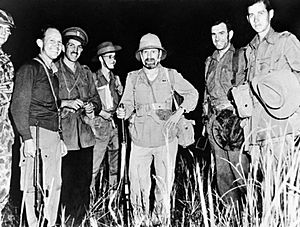

Wingate set out from Imphal on 12 February 1943. The Chindits were organized into eight separate groups. They crossed the Chindwin river. The force had early success in damaging a main railway in Burma. Then Wingate led them deep into Burma and across the Irrawaddy River.

However, conditions were very different from what they expected. The area was dry and had many roads. The Japanese used these roads to their advantage, especially by stopping supplies dropped to the Chindits. The Chindits soon suffered badly from tiredness, lack of water, and food shortages.

On 22 March, army headquarters ordered Wingate to bring his units back to India. They faced the challenge of the Japanese focusing on destroying them. They decided to go back to the Irrawaddy River. The Japanese would not expect this. Then, they would split into small groups to attack the enemy as they returned to the Chindwin.

By mid-March, three Japanese infantry divisions were chasing the Chindits. The Chindits were trapped near the Shweli River. They could not cross the river easily and reach British lines. So, they split into small groups to avoid the enemy. The Japanese worked hard to stop air supplies to the Chindits. They also removed boats from rivers to make it harder for them to move. The force returned to India in groups during the spring of 1943. They came back by different routes, some directly, others through China. They were constantly attacked by the Japanese. Casualties were high, and the force lost about one-third of its total strength.

The Second Chindit Mission

After meeting with Allied leaders, Wingate got typhoid on his way back to India. His illness prevented him from taking a more active role in training new long-range jungle forces.

While Wingate was still in Burma, Wavell had ordered the creation of 111 Brigade, also known as the "Leopards." This brigade was similar to the 77 Brigade. Wavell planned for the two brigades to work together. One would be on operations while the other trained.

However, once back in India, Wingate was promoted to acting major general. He was given six brigades. This meant breaking up the experienced 70th Division. Other commanders felt this division could be better used as a regular army unit.

At first, Wingate suggested turning the entire front into one huge Chindit mission. He wanted to break up the whole Fourteenth Army into Long-Range Penetration units. He thought the Japanese would follow them around the Burmese jungle. This plan was quickly dropped. Other commanders pointed out that the Japanese Army would simply advance and capture the air bases that supplied the Chindit forces.

In the end, a new long-range jungle operation was planned. This time, it would use all six brigades given to Wingate. The second mission was meant to work with a planned regular army attack against northern Burma. But events on the ground led to the cancellation of the army attack. This left the long-range penetration groups without a way to transport all six brigades into Burma.

When Wingate returned to India, he found his mission had also been canceled because there was not enough air transport. Wingate was very disappointed. He told everyone who would listen, including Allied commanders like Colonel Philip Cochran. Cochran, from the 1st Air Commando Group, told Wingate that canceling the mission was not necessary. He explained that his group had 150 gliders to carry supplies. Wingate realized that gliders could also move a large number of troops. He immediately planned how his Chindits could be flown deep into the jungle and then spread out to fight the Japanese.

With this new glider option, Wingate decided to go into Burma anyway. The 1944 operations were different from 1943. This time, they aimed to set up strong bases in Burma. From these bases, the Chindits would launch attacks and block enemy movements. A similar strategy was used years later by the French in Indochina at Dien Bien Phu.

Operation Thursday

Wingate planned for part of 77 Brigade to land by glider in Burma. They would prepare airstrips for 111 Brigade and the rest of 77 Brigade to be flown in by C-47 transport planes. Three landing sites were chosen: "Piccadilly," "Broadway," and "Chowringhee."

On the evening of 5 March, Wingate, Lieutenant General Slim (the commander of Fourteenth Army), Brigadier Michael Calvert (commander of 77 Brigade), and Cochrane waited at an airfield in India. They were waiting for 77 Brigade to fly into "Piccadilly." An incident happened that some critics later said showed Wingate's lack of calm.

Wingate had forbidden constant scouting of the landing sites to keep the operation secret. But Cochrane ordered a last-minute flight. This flight showed "Piccadilly" was completely blocked with logs. According to Slim, Wingate became very emotional. He insisted the operation had been betrayed and that the Japanese would have set up ambushes at the other two sites. He left the decision to continue or cancel the operation to Slim.

Slim ordered the operation to go ahead. Wingate then ordered 77 Brigade to fly into "Chowringhee." Both Cochrane and Calvert objected. "Chowringhee" was on the wrong side of the Irrawaddy River, and Cochrane's pilots were not familiar with it. Eventually, "Broadway" was chosen instead.

The landings were difficult at first. Many gliders crashed on the way or at "Broadway." But Calvert's brigade quickly made the landing ground ready for aircraft. They sent the signal that they had succeeded. Later, it was found that the logs on "Piccadilly" had been placed there by Burmese teak loggers to dry.

Once all the Chindit brigades (except one that stayed in India) had arrived in Burma, they set up base areas and supply drop zones behind Japanese lines. By good timing, the Japanese launched an invasion of India around the same time. By fighting several battles along their path, the Chindit groups were able to disrupt the Japanese attack. They forced Japanese troops away from the main battles in India.

The usefulness of Wingate's Chindits has been debated. Field Marshal William Slim argued that special forces often took the best-trained troops away from the main army. However, Sir Robert Thompson, a Chindit veteran, wrote that Wingate was "unquestionably one of the great men of [the 20th] century."

Regarding Operation Thursday, historian Raymond Callahan said that "Wingate’s ideas were flawed in many respects." He noted that the Japanese Army did not have Western-style supply lines to disrupt. However, the Japanese commander, Mutaguchi Renya, later said that Operation Thursday had a big effect on the campaign. He stated, "The Chindit invasion... had a decisive effect on these operations... they drew off the whole of 53 Division and parts of 15 Division."

Death in India

On 24 March 1944, Wingate flew to check on three Chindit bases in Burma. On his way back, he agreed to give two British war reporters a ride. The pilot protested that the plane was too heavy. The USAAF B-25 Mitchell bomber crashed into jungle-covered hills in northeast India. All ten people on board died, including Wingate. He died as an acting major general.

Brigadier (later Lt.-Gen.) Walter Lentaigne was appointed to take over command of the LRP (Long-Range Penetration) forces. He flew out of Burma to take command as Japanese forces began their attack on Imphal. Command of Lentaigne's 111 Brigade in Burma was given to Lt. Col. J.R. 'Jumbo' Morris.

Wingate and the nine other crash victims were first buried in a shared grave near the crash site. This was close to the village of Bishnupur. Since five of the ten victims, including both pilots, were American, all ten bodies were dug up in 1947. They were reburied in Imphal, India. Then, in 1950, they were dug up again and flown to Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia for reburial. This was done with an agreement between the governments of India, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and with the families' wishes.

Commemoration and Legacy

In a tribute to Wingate, Churchill called him "one of the most brilliant and courageous figures of the second world war." He also said Wingate was "a man of genius who might well have become also a man of destiny."

A memorial to Orde Wingate and the Chindits stands in London. It is on the north side of the Victoria Embankment, near the Ministry of Defence headquarters. The front of the memorial honors the Chindits and four men who received the Victoria Cross. The battalions that took part are listed on the sides. The back of the monument is dedicated to Orde Wingate. It also mentions his help for the state of Israel.

To honor Wingate's great help to the Zionist cause, Israel's National Centre for Physical Education and Sport was named after him. It is called the Wingate Institute (Machon Wingate). A square in the Talbiya neighborhood of Jerusalem, Wingate Square (Kikar Wingate), also has his name. So does the Yemin Orde youth village near Haifa. A Jewish football club formed in London in 1946, Wingate Football Club, was also named in his honor.

The General Wingate School in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, remembers Orde Wingate's help. He, along with the Gideon Force and Ethiopian Patriots, helped free Ethiopia in 1941.

A memorial stone in his honor stands in Charlton Cemetery, London. Other members of the Orde Browne family are buried there. There is also a memorial in Charterhouse School Chapel.

Wingate Golf Club in Harare, Zimbabwe, is named after the general. Photographs of him are in the Clubhouse. The club was created to welcome Jewish and Catholic members. This was because The Royal Harare Golf Club did not admit them in the past.

The deep-penetration tactics that the Chindits pioneered were later used by the Indonesian National Army. This was during the Indonesian National Revolution against the Netherlands. When traditional defense tactics failed, Indonesian General A.H. Nasution ordered units to carry out 'Wingate' actions. This meant going behind enemy lines and setting up resistance areas. This happened during the final stages of the revolution in 1948.

Family Life

Orde Wingate had a wife named Lorna. Their son, Lt Col Orde Jonathan Wingate, was born six weeks after his father's death. He joined the Honourable Artillery Company after a career in the Royal Artillery. He became the regiment's commanding officer. He died in 2000 at age 56. He was survived by his wife and two daughters.

He was also related to Reginald Wingate and Ronald Wingate. The Governor of Malta, Sir William Dobbie, was his uncle.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Orde Wingate para niños

In Spanish: Orde Wingate para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |