Indonesian National Revolution facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Indonesian National Revolution |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of the Second World War and Decolonisation of Asia | |||||||

Clockwise from top right:

Remains of the car of Brigadier Aubertin Walter Sothern Mallaby, where he was killed on 30 October 1945 during the Battle of Surabaya

A village near Bandung, where a number of houses were set on fire. Two Indonesian soldiers are visible on the left of the picture. Delegations of Indonesia and Netherlands arriving at Linggarjati Hill ahead of the Linggadjati Agreement Padang, West Sumatra, after Operation Kraai Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta before their exilement to Brastagi, North Sumatra Queen Juliana of the Netherlands signing the Soevereiniteitsoverdracht (Transfer of Sovereignty) of Indonesia. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Internal Conflict: |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

and others... |

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

The Indonesian National Revolution, also known as the Indonesian War of Independence, was a big fight for freedom. It involved armed conflict and talks between the new Republic of Indonesia and the Dutch Empire. It also included a social revolution within Indonesia itself. This important time happened right after World War II and the end of colonial rule in Indonesia.

The revolution lasted for four years, from Indonesia's declaration of independence in 1945 until the Netherlands officially gave up control in late 1949. During this time, there were fierce battles, big changes within Indonesian society, and two major international efforts to find peace. Dutch forces, along with their allies, could control big cities and important industrial areas. But they struggled to control the countryside. By 1949, many countries, especially the United States, put pressure on the Netherlands. The U.S. even threatened to stop financial aid for rebuilding after World War II. This pressure, along with a military stalemate, led the Netherlands to finally recognize Indonesia's independence.

This revolution ended the long period of Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia, except for Dutch New Guinea. It also changed the social classes and reduced the power of many local rulers. While it didn't immediately make life much better for most people, some Indonesians gained more power in business and trade.

Contents

How Indonesia's Fight for Freedom Began

The idea of Indonesian independence started growing around May 1908. This date is now celebrated as "Day of National Awakening." Groups like Budi Utomo, the Indonesian National Party (PNI), and Sarekat Islam quickly gained popularity. They wanted Indonesia to be free from Dutch control. Some groups tried to work with the Dutch by joining the "People's Council." They hoped this would lead to self-rule.

Other leaders, like Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta, chose a different path. They demanded full freedom from the Dutch East Indies colony. These leaders had benefited from new education policies, which helped them spread their nationalist ideas.

The Japanese occupation of Indonesia during World War II was a key event. Japan took control for three and a half years. The Netherlands couldn't defend its colony against the Japanese army. Within three months, Japan had taken over. In Java and Sumatra, the Japanese encouraged nationalist feelings. They did this to help themselves, but it also helped Indonesian leaders like Sukarno become more powerful. The Japanese also destroyed much of the Dutch system of economy and government. This made it harder for the Dutch to return.

On 7 September 1944, as the war turned against Japan, Prime Minister Koiso promised Indonesia independence. No date was set, but this promise made Sukarno's supporters feel that working with the Japanese had been the right choice.

Indonesia Declares Independence

Young and passionate groups, called pemuda (youth), pushed for immediate action. So, on 17 August 1945, just two days after Japan surrendered in World War II, Sukarno and Hatta declared Indonesia's independence. The very next day, a special committee chose Sukarno as President and Hatta as Vice-president.

PROCLAMATION

We, the people of Indonesia, hereby declare the independence of Indonesia.

Matters which concern the transfer of power and other things will be executed by careful means and in the shortest possible time.

Djakarta, 17 August 1945

In the name of the people of Indonesia,

[signed] Soekarno—Hatta

(translation by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, October 1948)

The Revolution Begins: Bersiap Period

It took a few weeks for the news of independence to reach all parts of Indonesia. Many people far from the capital, Jakarta, didn't believe it at first. But as the news spread, most Indonesians supported the new Republic. A feeling of revolution swept across the country. The balance of power had changed. It would be weeks before Allied forces arrived in Indonesia. This delay was partly due to strikes in Australia against Dutch ships. The Japanese, who were still in Indonesia, were told to keep order but also to surrender their weapons. Some Japanese soldiers gave their weapons to trained Indonesians.

This created a power vacuum, a time of uncertainty but also opportunity for the Republicans. Many pemuda joined groups fighting for the Republic. The most organized were soldiers from Japanese-trained armies that had been disbanded. Other groups were less organized but full of revolutionary spirit. In the first few weeks, Japanese troops often left cities to avoid conflict.

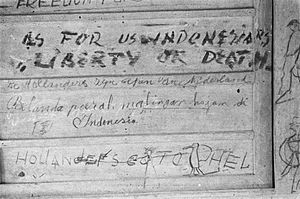

By September 1945, Republican youth groups had taken control of important places like railway stations in Java's biggest cities. They faced little resistance from the Japanese. To spread their message, pemuda set up radio stations and newspapers. Walls were covered with nationalist graffiti. On most islands, committees and local armies were formed. Republican newspapers were popular in Jakarta, Yogyakarta, and Surakarta. This inspired a generation of writers who felt their work was part of the revolution.

Republican leaders had to deal with strong public feelings. Some wanted a fierce armed struggle, while others preferred a calmer approach through diplomacy. Leaders like Tan Malaka believed the revolution should be led by the Indonesian youth. Sukarno and Hatta, however, focused on planning the new government and gaining independence through talks. Large pro-revolution protests happened in cities, including one in Jakarta with over 200,000 people. Sukarno and Hatta managed to calm this crowd.

By September 1945, many pemuda were impatient. They were ready to die for "100% freedom." During this time, known as the Bersiap period (1945–46), ethnic groups like Dutch, Eurasians, Ambonese, and Chinese were often targeted. Anyone thought to be a spy faced threats, kidnappings, robberies, and even killings. These attacks continued throughout the revolution but were most common in 1945–46.

Estimates of deaths during the Bersiap period range from 3,500 to 30,000. The NIOD Institute, a Dutch research group, estimated about 5,500 Dutch casualties, possibly up to 10,000. Many Indonesian fighters also died, especially before and during the Battle of Surabaya. Japanese forces lost about 1,000 soldiers, and British forces lost 660, mostly Indian soldiers. The Dutch military was not heavily involved at this early stage.

Setting Up the Republican Government

By late August 1946, a central Republican government was formed in Jakarta. It used a constitution written during the Japanese occupation. Since general elections hadn't happened yet, a Central Indonesian National Committee (KNIP) was appointed to help the President. Similar committees were set up in provinces and smaller regions.

Local rulers had to decide who to support. Rulers in Central Java quickly declared loyalty to the Republic. But many rulers on the outer islands, who had benefited from Dutch support, were less eager. This was partly because the Republican leaders were often from Java, not aristocrats, and sometimes had strong Islamic beliefs. However, some support came from South Sulawesi and from Makassarese and Bugis rulers. Many Balinese rulers also accepted Republican authority.

The new Republican Government and its leaders quickly worked to strengthen their young administration. They feared the Dutch would try to take back control. The government was enthusiastic but fragile, mostly focused on Java. It had little contact with the outer islands, which had more Japanese troops and fewer Republican activists. In November 1945, a parliamentary government was set up, and Sjahrir became Prime Minister.

After the Japanese surrender, their trained Indonesian military groups were disbanded. This meant the new Republican armed forces had to start from scratch. They grew from younger, less trained groups led by strong leaders. Creating an organized army that followed central authority was a huge challenge. In the new Indonesian army, Japanese-trained officers were more common than Dutch-trained ones. A 30-year-old former teacher, Sudirman, was chosen as 'commander-in-chief' in Yogyakarta on 12 November 1945.

Allied Response to the Revolution

The Dutch accused Sukarno and Hatta of working with the Japanese. They called the Republic a creation of Japanese fascism. The Dutch East Indies government had just received a $10 million loan from the United States to help them return to Indonesia.

Allied Occupation of Indonesia

The Netherlands was very weak after World War II in Europe. They couldn't send a large military force until early 1946. So, the Japanese and Allied forces reluctantly agreed to act as temporary caretakers. Since U.S. forces were focused on Japan, British Admiral Earl Louis Mountbatten was put in charge of Southeast Asia, including Indonesia. Allied groups already existed in parts of Borneo, Maluku, and Irian Jaya. Dutch officials had already returned to these areas. In Japanese naval areas, Allied troops quickly stopped revolutionary activities. Australian troops, followed by Dutch troops, took the Japanese surrender there, except for Bali and Lombok. Because there wasn't strong resistance, two Australian Army divisions easily took over eastern Indonesia.

The British were tasked with bringing back order and civilian government in Java. The Dutch thought this meant bringing back their old colonial rule. But the British and Indian troops didn't land on Java until late September 1945. Lord Mountbatten's main jobs were to send 300,000 Japanese soldiers home and free prisoners of war. He didn't want to use his troops in a long fight to get Indonesia back for the Dutch. The first British troops arrived in Jakarta in late September 1945. They reached other cities like Medan, Padang, Palembang, Semarang, and Surabaya in October. To avoid clashes, the British commander sent former Dutch colonial army soldiers to eastern Indonesia, where the Dutch were taking over smoothly. But tensions grew as Allied troops entered Java and Sumatra. Fights broke out between Republicans and those they saw as enemies: Dutch prisoners, Dutch colonial troops, Chinese, Eurasians, and Japanese.

The first battles started in October 1945. The Japanese tried to take back control of towns and cities, as their surrender terms required. Japanese military police killed Republican youth in Pekalongan on 3 October. Japanese troops drove Republican youth out of Bandung and gave the city to the British. But the fiercest fighting involving the Japanese was in Semarang. On 14 October, British forces began to occupy Semarang. Retreating Republican forces killed between 130 and 300 Japanese prisoners. Five hundred Japanese and two thousand Indonesians died. The Japanese had almost captured the city six days later when British forces arrived. The Allies sent the remaining Japanese troops and civilians back to Japan. However, about 1,000 Japanese chose to stay and later helped Republican forces fight for independence.

The British then decided to evacuate 10,000 European prisoners from Central Java. British groups sent to Ambarawa and Magelang faced strong Republican resistance. They used air attacks against the Indonesians. Sukarno arranged a ceasefire on 2 November. But by late November, fighting started again, and the British pulled back to the coast (see Battle of Ambarawa). Republican attacks against Allied and pro-Dutch civilians peaked in November and December. In Bandung, 1,200 people were killed as the youth groups went on the attack again. In March 1946, Republicans burned down much of southern Bandung before leaving the city. This event is known as the "Bandung Sea of Fire." The last British troops left Indonesia in November 1946. By this time, 55,000 Dutch troops had landed in Java.

The Battle of Surabaya

The Battle of Surabaya was the biggest and bloodiest battle of the revolution. It became a national symbol of Indonesian resistance. Youth groups in Surabaya, Indonesia's second-largest city, took weapons and ammunition from the Japanese. They formed two new groups: the Indonesia National Committee (KNI) and the People's Security Council (BKR). By the time Allied forces arrived in late October 1945, the youth groups had made Surabaya a "strong unified fortress."

In September and October 1945, Indonesian crowds attacked and killed Europeans and pro-Dutch Eurasians. Fierce fighting began when 6,000 British Indian troops landed in the city. Sukarno and Hatta negotiated a ceasefire between the Republicans and the British forces led by Brigadier Mallaby. Mallaby was killed on 30 October 1945 while trying to spread news of the ceasefire. After his death, the British sent more troops into the city on 10 November, with air support. Even though the European forces largely captured the city in three days, the poorly armed Republicans fought until 29 November. Thousands died as people fled to the countryside.

Despite this military loss for the Republicans, the battle united the nation in support of independence. It also helped Indonesia get international attention. For the Dutch, it proved that the Republic was a well-organized resistance with strong public support. It also convinced Britain to stay neutral in the revolution. Within a few years, Britain would even support Indonesia's cause in the United Nations. The last British troops left Indonesia in November 1946, but by then, 55,000 Dutch troops had arrived in Java.

Dutch Civil Administration Returns

With British help, the Dutch brought their Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA) forces to Jakarta and other key areas. Republican sources reported 8,000 deaths in Jakarta's defense by January 1946, but they couldn't hold the city. So, the Republican leaders moved to Yogyakarta, with strong support from the new sultan, Sri Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX. Yogyakarta became very important in the revolution and was later given special territory status. In Bogor and Balikpapan, Republican officials were arrested. To prepare for Dutch occupation of Sumatra, its largest cities, Palembang and Medan, were bombed. In December 1946, a special forces unit led by Captain Raymond "Turk" Westerling was accused of using harsh methods to control the southern Sulawesi region. As many as 3,000 Republican fighters and supporters were killed in a few weeks.

On Java and Sumatra, the Dutch had military success in cities and major towns. But they couldn't control the villages and countryside. On the outer islands, Republican support was not as strong among the elite. So, the Dutch occupied these areas more easily and set up their own states. The largest was the State of East Indonesia (NIT), which covered most of eastern Indonesia. It was established in December 1946, with its capital in Makassar.

Talks and Military Actions

The Linggadjati Agreement

The Linggadjati Agreement, arranged by the British in November 1946, was a big step. The Netherlands agreed to recognize the Republic as the real authority over Java, Madura, and Sumatra. Both sides also agreed to form the United States of Indonesia by 1 January 1949. This would be a semi-independent federal state with the Dutch monarch as its head. The Republican-controlled Java and Sumatra would be one of its states. Other areas under stronger Dutch influence would also be states. The Indonesian National Committee (KNIP) didn't approve the agreement until February 1947. Neither the Republic nor the Dutch were fully happy with it. On 25 March 1947, the Dutch parliament approved a simpler version of the treaty, which the Republic didn't accept. Soon, both sides accused each other of breaking the agreement.

... [the Republic] became increasingly disorganised internally; party leaders fought with party leaders; governments were over thrown and replaced by others; armed groups acted on their own in local conflicts; certain parts of the Republic never had contact with the centre – they just drifted along in their own way.

The whole situation deteriorated to such an extent that the Dutch Government was obliged to decide that no progress could be made before law and order were restored sufficiently to make intercourse between the different parts of Indonesia possible, and to guarantee the safety of people of different political opinions.

Operation Product: Dutch Military Action

At midnight on 20 July 1947, the Dutch launched a major military attack called Operatie Product. Their goal was to destroy the Republic and take back control of areas with natural resources in Java and Sumatra. This would help pay for their large military presence. The Dutch claimed the Republic had broken the Linggajati Agreement. They called their campaign "police actions" to bring back law and order. In this attack, Dutch forces pushed Republican troops out of parts of Sumatra, and East and West Java. The Republicans were forced into the Yogyakarta region of Java. The Dutch gained control of valuable plantations, oil, and coal facilities in Sumatra. In Java, they took control of all major ports.

Other countries reacted negatively to the Dutch actions. Neighboring Australia and newly independent India strongly supported the Republic in the UN. The Soviet Union and, most importantly, the United States also showed concern. Australian dockworkers continued to boycott Dutch ships, refusing to load or unload them. This blockade had started in September 1945. The United Nations Security Council got directly involved. It set up a Committee of Good Office (CGO) to help with negotiations. This made the Dutch diplomatic position very difficult. A ceasefire, called for by the UN, was ordered by the Dutch and Sukarno on 4 August 1947.

The Renville Agreement

The United Nations Security Council helped create the Renville Agreement to fix the problems from the Linggarjati Agreement. This agreement was approved in January 1948. It set a ceasefire line, called the 'Van Mook line', which marked the most advanced Dutch positions. However, many Republican positions were still behind Dutch lines. The agreement also said that people in Dutch-held areas would vote on their political future. The Republicans' willingness to negotiate gained them important support from America.

Talks between the Netherlands and the Republic continued through 1948 and 1949. Both internal and international pressures made it hard for the Dutch to decide what to do. Similarly, Republican leaders found it difficult to convince their people to accept diplomatic compromises. By July 1948, talks were stuck. The Netherlands then pushed ahead with its own plan for a federal Indonesia. New federal states like South Sumatra and East Java were created, but they didn't have much local support. The Netherlands set up a Federal Consultative Assembly (BFO) with leaders from these federal states. This group was supposed to form a United States of Indonesia and a temporary government by the end of 1948. However, the Dutch plans only gave the Republic a small role. Later plans didn't even mention the Republic. The main problem in talks was how much power the Dutch representative would have compared to the Republican forces.

Mistrust between the Netherlands and the Republic made negotiations difficult. The Republic feared another major Dutch attack. The Dutch were unhappy about continued Republican activity on their side of the Renville line. In February 1948, a Republican army battalion marched from West Java to Central Java. This move was meant to ease tensions within the Republican army. But the battalion clashed with Dutch troops while crossing Mount Slamet. The Dutch thought this was part of a planned troop movement across the Renville Line. This fear, along with Republican actions against Dutch-established states, made the Dutch leadership feel they were losing control.

Operation Crow and the General Offensive

We have been attacked .... The Dutch government have betrayed the cease-fire agreement. All the Armed Forces will carry out the plans which have been decided on to confront the Dutch attack

The Dutch were frustrated with negotiations. They believed the Republic was weakened by internal rebellions. So, on 19 December 1948, the Dutch launched another military attack called 'Operatie Kraai' (Operation Crow). By the next day, they had captured Yogyakarta, the temporary Republican capital. By the end of December, all major Republican cities in Java and Sumatra were in Dutch hands. The Republican president, vice-president, and most ministers were captured and sent to Bangka Island. In areas around Yogyakarta and Surakarta, Republican forces refused to surrender. They continued to fight a guerrilla war under the leadership of General Sudirman, who had escaped the Dutch attacks. An emergency Republican government was set up in West Sumatra.

Even though Dutch forces captured towns and cities, they couldn't control the villages and countryside. Republican troops and local fighters, led by Lt. Colonel Suharto (who later became president), attacked Dutch positions in Yogyakarta at dawn on 1 March 1949. The Dutch were forced out of the city for six hours. But reinforcements arrived that afternoon. Indonesian fighters retreated, and the Dutch re-entered the city. This attack, known as the Serangan Oemoem or '1 March General Offensive', is remembered with a large monument in Yogyakarta. A big attack against Dutch troops in Surakarta on 10 August that same year resulted in Republican forces holding the city for two days.

Again, other countries were outraged by the Dutch military actions, especially the United Nations and the United States. U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall threatened to stop all economic aid to the Netherlands. This aid was vital for Dutch rebuilding after World War II. The United States had already given the Netherlands $1 billion in Marshall Plan funds. The Netherlands had spent almost half of this on its campaigns in Indonesia. Many important people in the U.S. felt that American aid shouldn't be used to support "old-fashioned imperialism." This led to more support for Indonesian independence.

Internal Challenges and Conflicts

The revolution also saw internal conflicts, sometimes called "social revolutions" and rebellions by Communist and Islamist groups. These conflicts had common causes. There was a big divide between nationalist groups and traditional aristocrats. The Japanese had demanded a lot of labor and rice, causing hardship. There was also a lack of central authority, strong Islamic feelings that helped mobilize people, and the actions of small, secret revolutionary groups.

Social Revolutions and Changes

The "social revolutions" after independence were challenges to the old social order set up by the Dutch. They were also partly a result of anger against Japanese policies. Across the country, people rose up against traditional aristocrats and village leaders. They tried to take control of land and other resources. Most of these social revolutions ended quickly. In most cases, the challenges to the social order were put down. However, in East Sumatra, the sultanates were overthrown, and many aristocratic families were killed.

A culture of violence, born from the deep conflicts during the revolution, would appear again later in the 20th century. The term 'social revolution' describes various violent actions, some aimed at real change, others driven by revenge or a desire for power. Violence was a lesson learned during the Japanese occupation. People seen as 'feudal' – like kings, regents, or simply the wealthy – were often attacked. For example, in the coastal sultanates of Sumatra and Kalimantan, sultans and others who had been supported by the Dutch were attacked as soon as the Japanese left. In Aceh, the pro-Dutch aristocratic administrators were killed during a local civil war. Their place was taken by pro-Republican religious leaders.

Many Indonesians lived in fear. This was especially true for those who supported the Dutch or lived under Dutch control. The popular revolutionary cry "Freedom or Death" was sometimes used to justify killings. Traders faced difficult choices. Republicans pressured them to boycott sales to the Dutch. But Dutch police were harsh in stopping smugglers, on whom the Republican economy depended. In some areas, the phrase kedaulatan rakyat ('exercising the sovereignty of the people') was used not only to demand free goods but also to justify extortion and robbery. Chinese merchants, in particular, were often forced to sell their goods at very low prices under threat of death.

Communist and Islamist Rebellions

On 18 September 1948, a group of Communists declared an 'Indonesian Soviet Republic' in Madiun, east of Yogyakarta. They thought it was the right time for a workers' uprising against Sukarno and Hatta, whom they called "slaves of the Japanese and America." However, Republican forces quickly took back Madiun within a few weeks, and the rebellion leader, Musso, was killed. The governor of East Java and several others were killed by the rebels. This rebellion was a distraction for the revolution. It also turned vague American sympathy for Indonesia into strong diplomatic support. Internationally, the Republic was now seen as strongly anti-communist and a possible ally in the growing Cold War.

Some members of the Republican Army felt betrayed by the Indonesian Government for signing the Renville Agreement. They felt it recognized too many areas behind the Dutch line as Dutch territory. In May 1948, they declared their own state, the Negara Islam Indonesia (Indonesian Islamic State), better known as Darul Islam. Led by Sekarmadji Maridjan Kartosuwirjo, Darul Islam wanted to make Indonesia an Islamic country. At the time, the Republican Government didn't react much because they were focused on the Dutch threat. Some leaders of the Masjumi party sympathized with the rebellion. After the Republic regained all territories in 1950, the government took the Darul Islam threat seriously. The last group of rebels was defeated in 1962.

Indonesia Gains Full Independence

Millions upon millions flooded the sidewalks, the roads. They were crying, cheering, screaming "... Long live Bung Karno ..." They clung to the sides of the car, the hood, the running boards. They grabbed at me to kiss my fingers.

Soldiers beat a path for me to the topmost step of the big white palace. There I raised both hands high. A stillness swept over the millions. "Alhamdulillah – Thank God," I cried. "We are free"

The strong resistance of the Indonesian Republic and active international diplomacy turned world opinion against the Dutch. The second 'police action' was a big diplomatic failure for the Dutch. The new United States Secretary of State Dean Acheson pushed the Netherlands government into negotiations. The Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference was held in The Hague from 23 August to 2 November 1949. It involved the Republic, the Netherlands, and the Dutch-created federal states. The Netherlands agreed to recognize Indonesian sovereignty over a new federal state called the 'United States of Indonesia' (RUSI). This new state would include all the territory of the former Dutch East Indies, except for Dutch New Guinea. It was agreed that the Netherlands would keep control over New Guinea for another year, until further talks. Indonesia also agreed to pay the Dutch East Indies' debt, which was 4.5 billion guilders. This meant Indonesia paid for the colonial government's expenses during the "police actions." Sovereignty was officially transferred on 27 December 1949. The United States immediately recognized the new state.

Republican-controlled Java and Sumatra formed one state in the seven-state, nine-territory RUSI federation. They accounted for almost half of its population. The other fifteen 'federal' states and territories had been created by the Netherlands since 1945. These smaller states gradually joined the Republic in the first half of 1950. An attempted coup in Bandung and Jakarta by Westerling's Legion of the Just Ruler (APRA) on 23 January 1950 failed. This led to the dissolution of the populous Pasundan state in West Java, speeding up the end of the federal structure. Colonial soldiers, mostly from Ambon, clashed with Republican troops in Makassar during the Makassar Uprising in April 1950. The Christian Ambonese were one of the few groups with pro-Dutch feelings. They were suspicious of the Javanese Muslim-dominated Republic, seeing them as leftists. On 25 April 1950, an independent Republic of South Maluku (RMS) was declared in Ambon. But Republican troops put down this rebellion between July and November. With the state of East Sumatra being the only federal state left, it also joined the unitary Republic. On 17 August 1950, five years after declaring independence, Sukarno proclaimed the Republic of Indonesia as a unitary state.

Impact of the Revolution

Many Indonesians died during the revolution, far more than Europeans. Estimates of Indonesian deaths in fighting range from 45,000 to 100,000. Civilian deaths are estimated between 25,000 and 100,000. About 980 British soldiers were killed or went missing in Java and Sumatra in 1945 and 1946, mostly Indian soldiers. More than 5,000 Dutch soldiers died in Indonesia between 1945 and 1949. Many Japanese also died; in Bandung alone, 1,057 died. Seven million people were forced to leave their homes in Java and Sumatra.

The revolution had direct effects on the economy. Shortages of food, clothing, and fuel were common. There were two economies, Dutch and Republican, both trying to rebuild after World War II. The Republic had to create everything from 'postage stamps' to 'train tickets' while facing Dutch trade blockades. Different currencies were used at the same time—Japanese, new Dutch money, and Republican money—causing confusion and high inflation. The Indonesian government ended up with a large debt, which slowed down development. The last payment for the Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference debt was made in 2002.

Indonesia gained independence through a mix of diplomacy and force. Even though the youth groups were sometimes disorganized, their fighting against foreign and colonial forces was crucial. Without them, Republican diplomatic efforts might not have worked. The revolution is a turning point in modern Indonesian history. It shaped the country's main political trends that continue today. It boosted communism, strong nationalism, Sukarno's 'guided democracy', political Islam, the role of the Indonesian army, the country's constitution, and the centralization of power.

The revolution ended the colonial administration ruled from far away. It also removed the old local rulers, who many saw as outdated. It made the strict racial and social divisions of colonial Indonesia less rigid. Indonesians felt a huge burst of energy and hope. There was a new wave of creativity in writing and art, and a great demand for education and modernization. However, it didn't significantly improve the economic or political situation for the majority of poor farmers. Only a few Indonesians gained a larger role in business, and hopes for democracy faded within a decade.

Dutch Apologies for Past Actions

In 2013, the Netherlands government apologized for the violence used against the Indonesian people during the revolution.

In 2016, Dutch Foreign Minister Bert Koenders apologized for a massacre by Dutch troops that killed 400 Indonesian villagers in 1947.

During a state visit to Indonesia in March 2020, King Willem-Alexander made a surprise apology for "excessive violence" by Dutch troops.

On 17 February 2022, a major Dutch historical study was released. It was called Independence, Decolonization, Violence and War in Indonesia, 1945-1950. This research was done by three institutions. The study concluded that the Netherlands had used widespread and often deliberate extreme violence during the war. It stated that this violence "was condoned at every level: political, military and legal." On the same day, the Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte apologized for the terrible acts committed by the Dutch during the war. He also apologized for past Dutch governments' failure to acknowledge these actions.

See also

In Spanish: Revolución indonesia para niños

In Spanish: Revolución indonesia para niños

- Independence Day (Indonesia)

- List of high-ranking commanders of the Indonesian National Revolution

- Timeline of the Indonesian National Revolution

- United Nations Commission for Indonesia

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |