Suharto facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Suharto

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Official portrait, 1993

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd President of Indonesia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 12 March 1967 – 21 May 1998 Acting until 27 March 1968 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President |

See list

Hamengkubuwono IX (1973–1978)

Adam Malik (1978–1983) Umar Wirahadikusumah (1983–1988) Sudharmono (1988–1993) Try Sutrisno (1993–1998) B. J. Habibie (1998) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Sukarno | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | B. J. Habibie | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Cabinet Presidium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 25 July 1966 – 17 October 1967 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Sukarno (as Prime Minister) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Office abolished | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16th Secretary-General of the Non-Aligned Movement |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 September 1992 – 20 October 1995 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Dobrica Ćosić | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Ernesto Samper | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 8 June 1921 Bantoel, Dutch East Indies |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 27 January 2008 (aged 86) Jakarta, Indonesia |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Astana Giribangun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Golkar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Siti Hartinah

(m. 1947; died 1996) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 6, including Tutut, Titiek, and Tommy Suharto | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | KNIL Kadetschool | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nicknames |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1940–1974 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | General of the army | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit | Infantry (Kostrad) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Commands |

See list

Kodam IV/Diponegoro

Kostrad/Caduad Indonesian Army Kopkamtib Indonesian Armed Forces |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | List of awards | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service no. | 10684 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Suharto (born 8 June 1921 – died 27 January 2008) was an Indonesian military general and politician. He served as Indonesia's second president for a long time, from 1967 until 1998. He led Indonesia during a period known as the "New Order."

Suharto was born in Kemusuk, a village near Yogyakarta, when Indonesia was under Dutch rule. He grew up in a simple family. During the Japanese occupation, he joined Indonesian security forces. Later, he became part of the new Indonesian Army during Indonesia's fight for independence. He rose through the ranks to become a major general. In 1965, a political event known as the 30 September Movement occurred, which Suharto's troops helped to stop. This led to a period of significant political change in Indonesia.

In March 1967, Suharto became acting President. He was officially appointed President the next year. When he took office, Indonesia faced high inflation. He worked with economic advisors to introduce new policies that helped stabilize the economy. Under his leadership, Indonesia saw rapid growth in industries, better education, and more local businesses. He was even called "Father of Development" in 1982 for these achievements. However, there were also concerns about how the government was run and about financial dealings. These issues led to public dissatisfaction, especially during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Facing widespread protests, Suharto resigned in May 1998.

Suharto passed away in January 2008 and received a state military funeral. His time as president is still discussed today. Some praise him for bringing economic success and stability to Indonesia. Others point to his strong leadership style and concerns about human rights during his rule. On 10 November 2025, Suharto was granted the status of National Hero. This decision led to further discussions about his legacy.

Contents

Understanding Suharto's Name

Like many Javanese people, Suharto had only one name. The spelling "Suharto" is used today, but when he was born, it was spelled "Soeharto." He used this original spelling throughout his life.

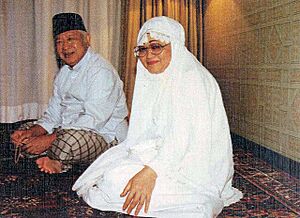

After a special pilgrimage called the Hajj in 1991, he was given the Islamic name "Mohammad." He also received the title Hajji. From then on, he was known as Haji Mohammad Suharto.

Suharto's Childhood and Family Life

Suharto was born on 8 June 1921 in a small house in Kemusuk, a village near Yogyakarta. This was during the time when Indonesia was known as the Dutch East Indies. His parents were Javanese, and he was the only child from his father's second marriage. His father, Kertosudiro, worked as a village irrigation official.

Suharto's parents divorced when he was very young. He lived with different family members during his childhood. At one point, he lived with his great-aunt, and later with his mother and stepfather. He also lived with his father's sister and her husband, Prawirowihardjo, who helped raise him.

He attended primary school in Wonogiri. Later, he moved back to Kemusuk and continued his studies at a middle school in Yogyakarta. Unlike some other Indonesian leaders, Suharto did not show much interest in politics or fighting against colonial rule when he was young. He learned to speak Dutch later, after joining the military.

Suharto's Military Career

After finishing middle school at 18, Suharto worked at a bank. In June 1940, he joined the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL). He trained in Gombong and became a sergeant.

Service During Japanese Occupation

In March 1942, the Dutch surrendered to Japanese forces. Suharto left the KNIL and later joined the Yogyakarta police force. In October 1943, he moved to a Japanese-sponsored militia called the Pembela Tanah Air (PETA). Here, Indonesians served as officers.

Suharto trained as a platoon commander and later as a company commander. This training taught him a local version of the Japanese "way of the warrior." This experience shaped his thinking about nationalism and military strength.

Role in the Indonesian National Revolution

After Japan surrendered in August 1945, Indonesia declared its independence. Suharto joined the new Indonesian Army. He quickly became a battalion commander. He fought against Allied troops around Magelang and Semarang. He earned respect as a field commander.

In December 1948, the Dutch captured the capital, Yogyakarta. Suharto led a guerrilla force against the Dutch. His forces briefly recaptured the city in March 1949. This event showed that the Dutch had not won the war. The United Nations Security Council then pushed the Dutch to negotiate. This led to the Dutch leaving Yogyakarta in June 1949.

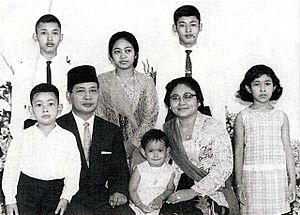

During the Revolution, Suharto married Siti Hartinah, also known as Tien. Their marriage was strong and supportive. They had six children: Tutut, Sigit Harjojudanto, Bambang Trihatmodjo, Siti Hediati Hariyadi, Hutomo Mandala Putra, and Siti Hutami Endang Adiningish.

After Indonesia's Independence

After Indonesia became fully independent, Suharto continued to serve in the Indonesian National Army. In 1950, he helped stop a rebellion in Makassar. He also worked to defeat other uprisings in Central Java.

Between 1956 and 1959, he commanded the Diponegoro Division in Central Java. During this time, he became involved in activities to fund his military unit. This led to an investigation in 1959. He was then transferred to the army's Staff and Command School.

He was promoted to brigadier-general and later to major general. In 1961, he became head of the army's new Strategic Reserve (Kostrad). In 1962, he led Operation Mandala to gain western New Guinea from the Dutch. In 1965, he was involved in Indonesia's confrontation with Malaysia.

Suharto's Path to Power

Political Changes in Indonesia

In the mid-1960s, tensions grew between the military and communist groups in Indonesia. President Sukarno supported a proposal for armed peasants and workers, which the army leadership rejected. The economy was also struggling, with widespread poverty.

The military, nationalists, and Islamic groups worried about the growing influence of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). By 1965, the PKI had many members and was a powerful political force.

The 1965 Political Events and Aftermath

On 1 October 1965, a group called the "30 September Movement" took action, leading to the deaths of six army generals in Jakarta. Suharto, who was at a hospital with his son, quickly responded. He mobilized troops from Kostrad and special forces to take control of Jakarta.

Suharto announced that the 30 September Movement had tried to overthrow President Sukarno. He stated that he was in control of the army and would restore order. The poorly organized movement failed. Suharto's forces secured control of the army by 2 October.

Following these events, the army, along with civilian groups, began a campaign to remove communist influence from Indonesian society. This period involved significant political upheaval and affected many people.

Gaining Presidential Authority

President Sukarno still had support, so Suharto moved carefully. For 18 months, there were many political changes. Students protested against Sukarno's government and high inflation, receiving support from the army.

In February 1966, Sukarno promoted Suharto to lieutenant-general. On 11 March 1966, Sukarno signed a decree called Supersemar. This gave Suharto the authority to take necessary actions to maintain security. Using this power, Suharto banned the PKI and removed Sukarno's supporters from government and military positions.

The parliament, now with more Suharto supporters, passed resolutions against communism. They also stated that if Sukarno could not perform his duties, Suharto would become acting president. On 20 February 1967, Sukarno announced his resignation. On 12 March, Suharto was named acting president. A year later, on 27 March 1968, Suharto was elected president for a full five-year term.

Suharto's New Order (1967–1998)

Guiding Principles of the New Order

Suharto's government was called the "New Order." It was based on the Pancasila ideology, which are the five founding principles of Indonesia. Suharto made it mandatory for all organizations in Indonesia to follow Pancasila. He also started training programs for all Indonesians about Pancasila.

The New Order also used a policy called Dwifungsi ("Dual Function"). This meant the military played an active role in all parts of the Indonesian government, economy, and society.

Economic Development Strategies

When Suharto became president, Indonesia was one of the poorest countries in Asia. Inflation was very high. Suharto understood that improving the economy was key. He appointed a group of economic advisors, sometimes called the "Berkeley Mafia." They introduced free market policies, which were different from previous government controls.

These policies helped lower inflation significantly. Suharto also encouraged foreign investment in Indonesia. He traveled to other countries to promote investment. Companies like Freeport Sulphur Company were among the first foreign investors. Local businesses, especially Chinese-Indonesian entrepreneurs, also grew.

The government received financial aid from other countries. With these funds and money from oil exports, Indonesia invested in infrastructure. They created a series of five-year plans called REPELITA to guide this growth.

Strengthening Government Control

After becoming president, Suharto worked to strengthen his power. He was supported by a group of military officers. He carefully managed relationships with other generals and political groups. He also made changes to the parliament and election laws.

The laws allowed for a parliament (MPR) that could elect presidents. Many members of the parliament were appointed by the government. This gave the government significant control over laws and presidential appointments.

Suharto used a group called Golkar ("Functional Groups") as his political party. In the first general election in 1971, Golkar won a large majority. This ensured Suharto's re-election as president.

"It is not the military strength of the Communists, but their fanaticism and ideology which is the principal element of their strength. To consider this, each country in the area needs an ideology of its own with which to counter the Communists. But a national ideology is not enough by itself. The well being of the people must be improved so that it strengthens and supports the national ideology."

To maintain control, the government merged political parties into two main groups: the PPP (Islamic parties) and the PDI (non-Islamic parties). Suharto was re-elected unopposed multiple times. Golkar consistently won elections, allowing Suharto to pass his agenda easily.

Suharto also created various civil society groups. These groups aimed to unite people in support of government programs. Examples include KORPRI for civil servants and FBSI for labor unions.

Social Programs and Progress

In the early 1970s, Suharto's government launched a family planning program. Suharto and his wife promoted its benefits across the country. This program helped improve public health.

A lasting change from this time was the spelling reform of the Indonesian language in 1972.

Government health programs helped increase life expectancy from 47 years in 1966 to 67 years in 1997. Infant mortality rates also dropped significantly. An education program in 1973 led to a high primary school enrollment rate. Indonesia also achieved self-sufficiency in rice production by 1984. This earned Suharto an award from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Maintaining Internal Order

Suharto used the military to maintain order within the country. Military officers were appointed to lead regions. This was part of the Dwifungsi policy. The government also took action against various insurgencies and extremist groups.

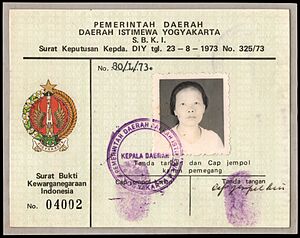

To help integrate Chinese-Indonesians, the government introduced new policies. These policies limited Chinese cultural expressions in public. Chinese schools were changed to Indonesian-language public schools. Ethnic Chinese people were also encouraged to adopt Indonesian-sounding names. In 1978, a Letter of Proof of Citizenship was required for citizens of foreign descent, mainly affecting Chinese Indonesians.

Indonesia's Foreign Relations

Suharto's government adopted a neutral stance during the Cold War. However, it quietly aligned with Western countries like the United States and Japan. This helped Indonesia get support for its economic recovery. Diplomatic relations with China were suspended in 1967 but restored in 1990.

Regionally, Indonesia ended its confrontation with Malaysia in 1966. In 1967, Indonesia became a founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). This organization aimed to promote peaceful relationships among Southeast Asian countries.

East Timor Conflict

In 1974, a conflict arose in the neighboring colony of Portuguese Timor. After Portugal withdrew, a left-wing group called Fretilin became powerful. With approval from some Western countries, Suharto decided to intervene. He stated this was to prevent a communist state from forming.

Indonesia became involved in East Timor in 1975 and officially annexed it as its 27th province in 1976. This led to a long period of conflict and challenges in East Timor.

Regarding West Irian, the Suharto government organized a process called the "Act of Free Choice" in 1969. This process led to West Irian integrating with Indonesia. The United Nations General Assembly noted this decision.

Economic Growth and Social Progress

Indonesia saw significant economic and social progress under Suharto. By 1996, the poverty rate had dropped to about 11% from 45% in 1970. The country's economy grew steadily. The manufacturing sector also expanded greatly. The government invested in large infrastructure projects, including telecommunication satellites.

In the early 1980s, Indonesia successfully shifted its economy to focus on manufacturing for export. This was helped by low wages and currency changes. Chinese-Indonesian companies grew into large businesses, playing a major role in the economy.

Suharto supported the growth of these companies. In return, they provided important funding for his government's activities.

In the late 1980s, the government made changes to the banking sector. This encouraged savings and provided more money for growth. The Jakarta Stock Exchange also saw a period of rapid growth. This led to strong economic growth in the early 1990s. However, the financial system's weak regulations later contributed to a major crisis.

Later Years of Suharto's Presidency

By the 1980s, Suharto maintained his power through controlled elections and military influence. He reorganized the armed forces to centralize power. He appointed General Leonardus Benjamin Moerdani as head of the armed forces, who took a firm approach to challenges.

Suharto's emphasis on Pancasila led to some protests from conservative Islamic groups. The Tanjung Priok massacre in 1984 involved the army and Muslim protesters. Attacks by the Free Aceh Movement in 1989 also led to military operations. The government also increased control over the press.

After the Cold War, there was more international attention on human rights in Indonesia. Suharto was elected head of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1992. Indonesia also became a founding member of APEC.

Domestically, concerns grew about the financial dealings of Suharto's family. To broaden his support, Suharto began to connect with Islamic groups. He made a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1991 and promoted Islamic values. He also formed the Indonesian Association of Muslim Intellectuals (ICMI).

By the 1990s, some members of Indonesia's growing middle class wanted reforms. They were concerned about the government's strong control and financial matters. In 1996, Megawati Sukarnoputri, Sukarno's daughter, became an opposition figure. This led to political tensions and protests.

Economic Challenges and Resignation

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis

Indonesia was severely affected by the 1997 Asian financial crisis. The value of the Indonesian currency, the rupiah, dropped sharply. Many companies faced bankruptcy, and the economy shrank. This led to higher unemployment and poverty.

The central bank tried to protect the rupiah, but it was difficult. Suharto signed agreements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for economic reforms. The government had to provide emergency financial aid to banks. Interest rates were also raised, which further slowed the economy.

Concerns grew that Suharto's family and friends were not following the strict IMF reforms. This further reduced confidence in the economy and his leadership. The economic problems were accompanied by increasing political tensions. There were public protests and ethnic clashes in several cities.

In March 1998, Suharto was re-elected for another five-year term. He appointed his protégé B. J. Habibie as vice president. He also included family members in his cabinet. These appointments and an unrealistic budget caused more financial instability and public panic. Fuel prices were increased, leading to more protests.

Suharto's Resignation

As Suharto was increasingly seen as the cause of the country's problems, political figures and university students began to protest. On 12 May 1998, security forces killed four student demonstrators in Jakarta. This led to widespread protests and unrest across Jakarta and other cities.

On 16 May, tens of thousands of students demanded Suharto's resignation. They occupied the parliament building. When Suharto returned to Jakarta, he offered to resign in 2003 and change his cabinet. However, his political allies withdrew their support.

On 21 May 1998, Suharto announced his resignation. Vice-president Habibie then became president, as stated in the constitution.

After the Presidency (1998–2008)

Illness and Passing

After leaving the presidency, Suharto lived a private life in Jakarta. He was hospitalized many times for health issues, including strokes and heart problems. His declining health made it difficult for any legal proceedings to move forward.

On 4 January 2008, Suharto was admitted to the hospital with serious health complications. His health worsened over several weeks due to various issues. He passed away on 27 January 2008, at 1:09 pm.

Indonesia's President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono declared Suharto one of Indonesia's "best sons." He invited the country to honor the former president. Suharto's body was taken to the Astana Giribangun mausoleum complex in Central Java. He was buried next to his late wife with a state military funeral. Many leaders offered their condolences. President Yudhoyono declared a week of national mourning.

Suharto's Legacy and Recognition

Template:Conservatism in Indonesia Since the early 2010s, a Javanese slogan, “Piye kabare, penak jamanku to?” (English: How are you doing? It was better in my time, right?), became popular in Indonesia. It appeared on stickers, t-shirts, and online, reflecting a public discussion about his era.

Surveys in 2011 and 2018 showed that many Indonesians viewed Suharto as a successful president.

On 25 September 2024, the People's Consultative Assembly removed a resolution that had accused Suharto of certain actions. This was because he was never tried for these accusations before his death. This action renewed discussions about whether Suharto should be recognized as a National Hero.

On 10 November 2025, Suharto was officially named a National Hero. This decision, made alongside nine other names, sparked public debate. Many people discussed his contributions to Indonesia's development and stability, while others raised concerns about his political actions during his time in power.

Memorials and Statues

Suharto's childhood home in Kemusuk is now a memorial museum. A statue of him stands in front of the museum.

FELDA Soeharto, a village in Selangor, Malaysia, is named after him. He visited the village in 1970 to improve relations between Indonesia and Malaysia.

The Istiklal Mosque in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, was started by Suharto as a gift. It is sometimes called the Suharto Mosque by locals.

Honours and Awards

National Honours from Indonesia

As a military officer and president, Suharto received many awards from Indonesia, including:

- Star of the Republic of Indonesia, 1st Class

- Star of Mahaputera, 1st Class

- Star of Merit, 1st Class

- The Sacred Star

- Star of Meritorious Service

- Guerrilla Star

- Star of Culture Parama Dharma

- Star of Yudha Dharma, 1st Class

- Star of Kartika Eka Paksi, 1st Class

- Star of Kartika Eka Paksi, 2nd Class

- Star of Kartika Eka Paksi, 3rd Class

- Star of Jalasena, 1st Class

- Star of Swa Bhuwana Paksa, 1st Class

- Star of Bhayangkara, 1st Class

- Garuda Star

- Indonesian Armed Forces 8 Years of Service Star

- Military Long Service Medal, 16 Years Service

- Military Campaign Medal

- 1st Campaign Commemoration Medal

- 2nd Campaign Commemoration Medal

- 1st Military Operations Service Medal

- 2nd Military Operations Service Medal

- 3rd Military Operations Service Medal

- 4th Military Operations Service Medal

- West New Guinea Military Campaign Medal

- Northern Borneo Military Campaign Medal

- Medal for Combat Against Communists

International Honours

He also received several awards from other countries:

- Order of the Liberator General San Martín (Argentina, 1972)

- Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria (Austria, 1973)

- Order of Leopold (Belgium, 1973)

- Family Order of Laila Utama (Brunei, 1988)

- National Order of Independence (Cambodia, 1968)

- Order of the Nile (Egypt, 1977)

- Order of the Queen of Sheba (Ethiopian Empire, 1968)

- National Order of the Legion of Honour (France, 1972)

- Order of Pahlavi (Pahlavi Iran)

- Commemorative Medal of the 2,500-year Celebration of the Persian Empire (Pahlavi Iran, 1971)

- Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (Italy, 1972)

- Order of the Chrysanthemum (Japan, 1968)

- Order of Al-Hussein bin Ali (Jordan, 1986)

- Order of Mubarak the Great (Kuwait, 1977)

- Order of the Crown of the Realm (Malaysia, 1988)

- Royal Family Order of Johor (Johor, Malaysia, 1990)

- Royal Family Order of Perak (Perak, Malaysia, 1988)

- Order of the Aztec Eagle (Mexico)

- Order of the Netherlands Lion (Netherlands, 1970)

- Nishan-e-Pakistan (Pakistan, 1982)

- Order of Sikatuna (Philippines, 1968)

- Order of the Golden Heart (Philippines, 1968)

- Order of the Independence (Qatar, 1977)

- Order of the Star of the Romanian Socialist Republic (Socialist Republic of Romania, 1982)

- Great Chain of the Badr (Saudi Arabia, 1977)

- Order of Temasek (Singapore, 1974)

- Order of Good Hope (South Africa, 1997)

- Grand Order of Mugunghwa (South Korea, 1981)

- Order of Isabella the Catholic (Spain, 1980)

- Order of the Umayyads (Syria, 1977)

- Order of the Rajamitrabhorn (Thailand, 1970)

- Order of the Republic (Tunisia, 1995)

- Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise (Ukraine, 1997)

- Order of Unity (United Arab Emirates, 1977)

- Order of the Bath (United Kingdom, 1974)

- Order of the Liberator (Venezuela, 1988)

- Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany, 1970)

- Order of the Republic (Yemen)

- Order of the Yugoslav Star (Yugoslavia, 1975)

See also

In Spanish: Suharto para niños

In Spanish: Suharto para niños

- History of Indonesia

- List of high-ranking commanders of the Indonesian War of Independence

- Timeline of Indonesian history