1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Mandatory Palestine |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Intercommunal conflict in Mandatory Palestine | |||||||

British soldiers on an armoured train car with two Palestinian Arab hostages used as human shields. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Jewish National Council Yishuv

|

Central Committee of National Jihad in Palestine (October 1937 – 1939)

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Raghib al-Nashashibi (from 1937) |

Political leadership: Local rebel commanders: Arab volunteer commanders: Sa'id al-'As † |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 25,000–50,000 British soldiers 20,000 Jewish policemen, supernumeraries and settlement guards 15,000 Haganah fighters 2,883 Palestine Police Force, all ranks (1936) 2,000 Irgun militants |

1,000–3,000 (1936–37) 2,500–7,500 (plus an additional 6,000–15,000 part-timers) (1938) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| British Security Forces: 262 killed c. 550 wounded Jews: c. 500 killed |

Arabs: c. 5,000 killed c. 15,000 wounded 108 executed 12,622 detained 5 exiled |

||||||

The 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine was a major uprising by Palestinian Arabs. It happened in Mandatory Palestine, which was controlled by Britain at the time. The Arabs wanted independence and an end to Jewish immigration and land purchases. They also wanted to stop the plan to create a "Jewish National Home."

This uprising happened when many Jewish immigrants were arriving. The Jewish population had grown a lot under British rule. Many Arab farmers, called fellahin, were losing their land and becoming poor. They moved to cities but still faced hardship. Before the revolt, there had been a cycle of attacks between Jews and Arabs since 1920. The revolt started after two Jews were killed by a group, and then two Arab workers were killed in return. This led to widespread violence.

The revolt had two main parts. The first part was a general strike that lasted from April to October 1936. This strike was a way for Arabs to protest peacefully. The second part, starting in late 1937, involved more fighting. Arab groups targeted British forces, and the British army fought back strongly. The British used harsh methods to stop the rebellion.

The revolt ended in 1939. It caused many deaths and injuries on both sides. It also had a big impact on the future of Palestine.

Contents

Why the Revolt Started

Economic Problems for Arabs

After World War I, many people in Palestine, especially farmers, became very poor. The British government, like the previous Ottoman rulers, collected high taxes on farms. Prices for farm goods also dropped. This, along with bad harvests, made farmers fall into debt.

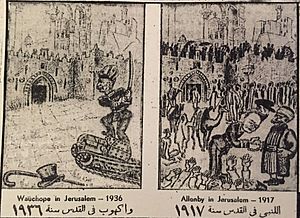

Many Arab farmers, known as fellahin, lost their land. This happened as land was sold to Jewish organizations. By 1931, a large number of Arab farmers had no land. The British High Commissioner, Arthur Wauchope, warned that this could cause serious problems.

Economic issues were a main reason for the revolt. Many Arab farmers moved to cities like Jaffa and Haifa. They often found only poverty there. Some found hope in the words of a preacher named Izz ad-Din al-Qassam. He worked with the poor in Haifa. The revolt grew from these struggles.

The British government tried to limit land sales from Arabs to Jews. But people found ways around these rules. The British also did not invest much in the economy or healthcare for Arabs. Jewish groups focused their investments only on Jewish settlements. This made things worse for Arabs.

Political and Social Changes

The arrival of Zionism (the movement to create a Jewish state) and British rule changed Palestinian society. It made Palestinian Arabs feel a stronger sense of national identity. They wanted to protect their traditions. Palestinian society was mostly based on family groups, called hamula.

New political groups formed in the 1930s. These included the Independence Party and the National Defence Party. Youth groups also appeared, like the Young Men's Muslim Association. Women's groups, like the Arab Women's Association, also became more involved in politics.

Inspiration from Other Countries

Arabs in Palestine saw that general strikes had worked in other Arab countries. In Iraq, a strike in 1931 led to independence from Britain. In Syria, a strike in 1936 led to a treaty with France. These events showed that strong protests could challenge colonial rule.

How the Revolt Began

In October 1935, a large shipment of weapons for the Haganah (a Jewish defense group) was found in Jaffa port. This made Arabs fear a Jewish military takeover. Soon after, a Jewish policeman was killed. The police searched for the killers and found Izz ad-Din al-Qassam. He was killed in a battle with police in November 1935.

Al-Qassam's death made many Palestinian Arabs very angry. Large crowds attended his funeral.

The revolt truly began five months later, on April 15, 1936. A group stopped a convoy and shot three Jewish passengers, killing two. They said they were avenging al-Qassam's death. The next day, two Arab workers were killed in revenge by Jewish gunmen.

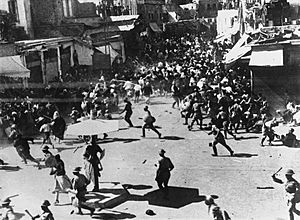

Violence spread quickly. Jews and Palestinians attacked each other in cities like Tel Aviv and Jaffa. By April 19, the situation was out of control. This led to a general strike and revolt across the country.

Key Events of the Revolt

The General Strike and Early Fighting (April–October 1936)

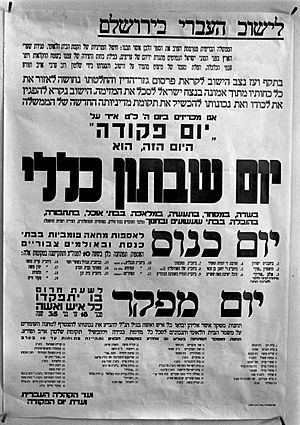

The strike started on April 19 in Nablus. Soon, similar groups formed in other towns. On April 21, major Arab leaders called for a general strike. This meant Arabs would stop working, using transport, and shopping.

On April 25, 1936, the Arab Higher Committee (AHC) was formed. This group led the strike. They demanded three things:

- Stop Jewish immigration.

- Stop Arabs from selling land to Jews.

- Create a Palestinian government with a representative council.

About a month into the strike, the AHC called for Arabs to stop paying taxes.

In the countryside, armed groups began to fight. They attacked the oil pipeline from Iraq to Haifa. They also attacked railways, trains, and Jewish settlements. Many Jewish farms were destroyed. Some Jewish communities had to leave their homes for safer areas.

The British responded harshly. They sent many soldiers to Palestine. They searched homes, arrested people, and took property. They also formed armed Jewish units to help as police. The British government believed the strike had strong support from Palestinian Arabs.

A Break in Fighting (October 1936 – September 1937)

The strike ended on October 11, 1936. The violence calmed down for about a year. During this time, a group called the Peel Commission studied the situation. They arrived in Palestine in November 1936.

The Peel Commission suggested dividing Palestine into a small Jewish state and a larger Arab state linked to Transjordan. They also suggested moving about 225,000 Palestinian Arabs from the proposed Jewish state.

The Arab Higher Committee immediately rejected these ideas. Jewish groups were also divided. The British government first accepted the plan. But they soon realized it would cause more problems with Arabs, especially with war coming in Europe. So, they decided not to go ahead with the partition plan.

Fighting Starts Again (September 1937 – August 1939)

When the Peel Commission's plan failed, the revolt started again in late 1937. A British official, Lewis Andrews, was killed in Nazareth. He was disliked by Palestinians for supporting Jewish settlement. The British then took stronger actions. They arrested Arab leaders and sent them away. They also closed borders and controlled the press.

In November 1937, a Jewish group called the Irgun began attacking Arab civilians. They called this "active defense." The British set up military courts to try people for crimes like carrying weapons or sabotage. But Arab attacks continued. Arab groups in the hills became more organized.

Violence lasted throughout 1938. The British sent even more troops to Palestine. By the end of the year, order was mostly restored in towns. But fighting continued in rural areas until World War II began in September 1939.

Attacks and Deaths

In the last 15 months of the revolt:

- 936 murders and 351 attempted murders happened.

- 2,125 shooting incidents occurred.

- 472 bombs were thrown.

- 364 armed robberies took place.

- 1,453 acts of sabotage against government property happened.

- 323 people were kidnapped.

- 236 Jews were killed by Arabs.

- 435 Arabs were killed by Jews.

- 1,200 rebels were killed by police and military.

What Happened After the Revolt

Impact on Jewish Community (Yishuv)

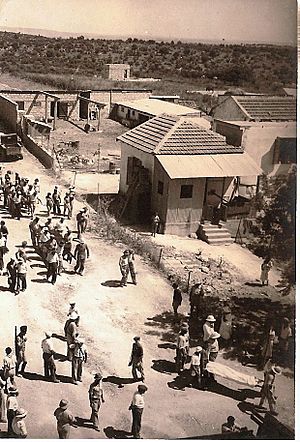

The Jewish community in Palestine, called the Yishuv, did not suffer huge losses. No Jewish settlements were destroyed, and many new ones were built. Over 50,000 new Jewish immigrants arrived during this time.

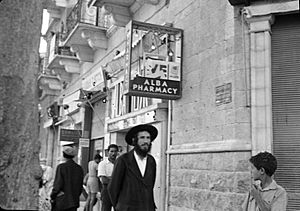

The fighting also led to Jewish and Arab economies becoming more separate. For example, the Jewish city of Tel Aviv built its own seaport. This was because the nearby Arab port of Jaffa was affected by the conflict. Jewish industries grew, and many young Jewish men gained military training.

Impact on Palestinian Arabs

The revolt weakened the Palestinian Arabs. The British took away many weapons from the Arab population. Also, many Arab leaders were exiled or killed. This made it harder for them to fight in the later 1948 Palestine war.

Thousands of Arab homes were destroyed. The general strike and fighting caused huge financial losses. The economy suffered from lost sales and increased joblessness.

The revolt did not achieve its main goals. However, it is seen as an important moment for the growth of Palestinian Arab identity. It also led to the British issuing the White Paper of 1939. This document limited Jewish immigration and suggested a single state for both Arabs and Jews in the future. However, the main Arab leader, Haj Amin al-Husseini, rejected this new policy.

Impact on the British Empire

As World War II approached, Britain needed the support of Arab governments. British leaders decided it was better to upset the Jews than the Arabs. In February 1939, Britain held a conference in London with Arab and Jewish leaders. But they could not agree.

The British then published the 1939 White Paper. This policy limited Jewish immigration. Many British officials felt tired of the problems in Palestine. One general, Bernard Montgomery, said, "The Jew murders the Arab and the Arab murders the Jew. This is what is going on in Palestine now. And it will go on for the next 50 years in all probability."

How Historians See the Revolt

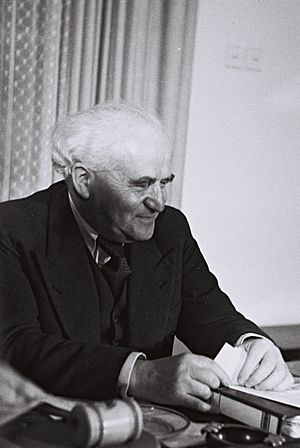

Historians sometimes overlook the 1936–39 Arab Revolt. Some Israeli historians focus more on the Jewish struggle for self-determination. They might describe the revolt as "events" or "riots." However, some Jewish leaders at the time, like David Ben-Gurion, understood that Arabs were fighting to keep their homeland.

Some historians also compare how Britain handled the revolt to how other countries dealt with rebellions. While Britain's actions were sometimes harsh, they are often seen as less extreme than those of other colonial powers. However, many villages were destroyed, and people suffered greatly. Britain did manage to stop the revolt, but it left Palestine in a difficult state.

|

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |