Kingdom of Italy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Italy

Regno d'Italia (Italian)

|

|

|---|---|

| 1861–1946 | |

|

Motto: FERT

(Motto for the House of Savoy) |

|

|

Anthem:

(1861–1943; 1944–1946) Marcia Reale d'Ordinanza ("Royal March of Ordinance")

(1943–1944) La Leggenda del Piave ("The Legend of Piave") |

|

Colonies and territories held by the Italian Empire in 1939

|

|

| Capital | |

| Largest city | Rome |

| Official languages | Italian |

| Religion | 96% Roman Catholicism (state religion) |

| Demonym(s) | Italian |

| Government | Unitary constitutional monarchy

|

| King | |

|

• 1861–1878

|

Victor Emmanuel II |

|

• 1878–1900

|

Umberto I |

|

• 1900–1946

|

Victor Emmanuel III |

| Prime Minister | |

|

• 1861 (first)

|

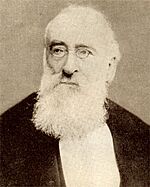

Count of Cavour |

|

• 1922–1943

|

Benito Mussolini |

|

• 1945–1946 (last)

|

Alcide De Gasperi |

| Legislature |

|

| Senate | |

|

|

| History | |

|

• Proclamation

|

17 March 1861 |

|

• Treaty of Vienna

|

3 October 1866 |

|

• Capture of Rome

|

20 September 1870 |

| 20 May 1882 | |

| 26 April 1915 | |

|

• March on Rome

|

28 October 1922 |

| 22 May 1939 | |

| 27 September 1940 | |

|

• Fall of Fascism

|

25 July 1943 |

|

• Republic

|

10 June 1946 |

| Area | |

| 1861 | 250,320 km2 (96,650 sq mi) |

| 1936 | 310,190 km2 (119,770 sq mi) |

| Population | |

|

• 1861

|

21,777,334 |

|

• 1936

|

42,993,602 |

| GDP (PPP) | 1939 estimate |

|

• Total

|

151 billion (2.82 trillion in 2019) |

| Currency | Lira (₤) |

The Kingdom of Italy (Italian: Regno d'Italia) was a country that existed from March 17, 1861, until June 10, 1946. It began when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was named King of Italy. It ended when the people voted to get rid of the monarchy and create the modern Italian Republic.

This kingdom was formed by bringing together many smaller states over several decades. This process was called the Risorgimento, which means "Resurgence" or "Rising Again." The Savoy family, who ruled the Kingdom of Sardinia, played a big part in making Italy one country.

In 1866, Italy fought against Austria and won the region of Veneto. In 1870, Italian troops took Rome, ending the Papal States' rule there. By the late 1800s, Italy started to gain colonies, like other big European countries. In 1882, Italy joined the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary.

However, Italy wanted more land from Austria-Hungary, so in World War I, it joined the Allied Powers. Italy won the war and got a permanent spot in the League of Nations. But it didn't get all the land it was promised.

In 1922, Benito Mussolini became prime minister. He started a period of National Fascist Party rule known as "Fascist Italy". During this time, Italy became a totalitarian dictatorship, meaning the government had total control. Mussolini focused on making Italy stronger, promoting traditional values, and expanding Italy's territory.

In 1929, Italy made peace with the Roman Catholic Church through the Lateran Treaties, which created Vatican City as an independent state. In the 1930s, Italy became more aggressive. It took over Ethiopia in 1935, helped in the Spanish Civil War in 1937, and invaded Albania in 1939. This led to Italy leaving the League of Nations and forming alliances with Germany and Japan.

Fascist Italy joined World War II in 1940 as a main member of the Axis Powers. After some early wins, Italy faced defeats in North Africa and the Soviet Union. When the Allies landed in Sicily in July 1943, Mussolini's government fell. The new government then surrendered to the Allies in September 1943.

German forces then took control of northern and central Italy. They set up the Italian Social Republic and put Mussolini back in charge. This led to a civil war in Italy. The Italian Co-belligerent Army and the resistance movement fought against Mussolini's forces and their German allies. After the war ended in 1945, the people of Italy voted in a referendum to become a republic, ending the monarchy in 1946.

Contents

- A Look at the Kingdom of Italy

- History of the Kingdom

- How Italy Became One Country (1848–1870)

- Italy's Economy and Growth

- Industrial Growth in Italy

- Social Changes and Emigration

- Education in the Kingdom

- The Liberal Era (1870–1914)

- World War I and the End of the Liberal State (1915–1922)

- Fascist Rule, World War II, and Civil War (1922–1946)

- Anti-Fascism Against Mussolini

- The End of the Kingdom (1946)

- Maps of Italy's Growth

- Changes to Italy's Coat of Arms

- See Also

A Look at the Kingdom of Italy

How Big Was Italy?

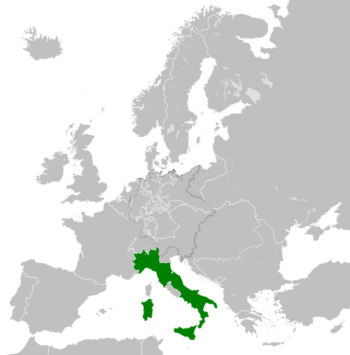

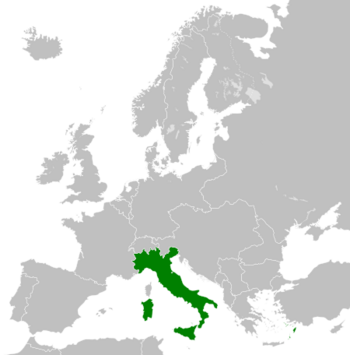

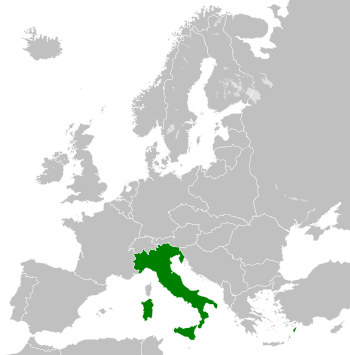

The Kingdom of Italy grew over time. It started with the Italian unification and kept adding land until 1870. In 1919, it gained Trieste and Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol.

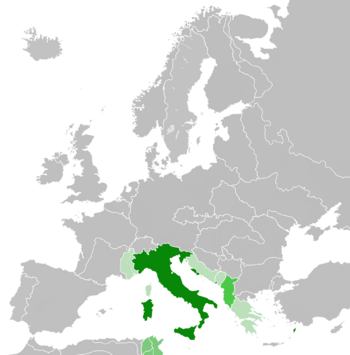

During World War II, Italy took more land from Yugoslavia after it broke apart in 1941. This included parts of Slovenia and Dalmatia.

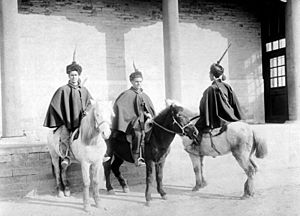

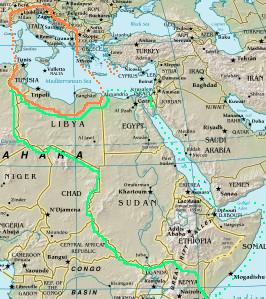

Italy also had colonies and controlled other lands outside its main borders. These included Eritrea, Italian Somaliland, Libya, and Ethiopia. It also controlled Albania and had a small area in Tianjin, China. These lands were controlled at different times and for different lengths of time.

How Italy Was Governed

The Kingdom of Italy was a constitutional monarchy. This means it had a king, but his power was limited by a constitution. The king appointed ministers who ran the government.

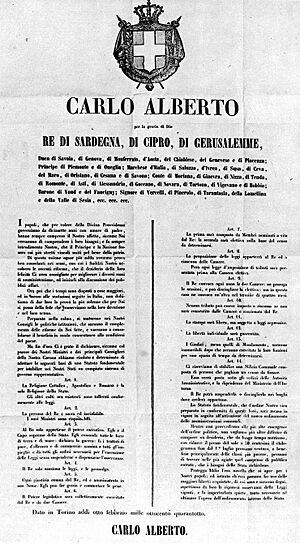

Italy had a two-part parliament. One part was the Senate, whose members were appointed. The other was the Chamber of Deputies, whose members were elected by the people. The country's constitution was the Statuto Albertino, which came from the Kingdom of Sardinia.

In theory, ministers only answered to the king. But in reality, the king couldn't keep a government in power if Parliament didn't agree.

For a short time in 1882, there were changes to how deputies were elected. After World War I, a new system called proportional representation was used. This meant parties got seats based on the percentage of votes they received.

Between 1925 and 1943, Italy became a Fascist dictatorship. The constitution was still technically in place, but the king accepted Fascist policies. In 1928, the Grand Council of Fascism took control of the government. In 1939, the Chamber of Deputies was replaced by the Chamber of Fasces and Corporations.

Italy's Military Forces

The military of the Kingdom of Italy included:

- King of Italy – The top commander of the Royal Italian Army, Navy, and Air Force.

- First Marshal of the Empire – A special top commander role during the Fascist era, held by both King Victor Emmanuel III and Benito Mussolini.

- Regio Esercito (Royal Italian Army)

- Regia Marina (Royal Italian Navy)

- Regia Aeronautica (Royal Italian Air Force)

- Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale (Voluntary Militia for National Security), also known as the "Blackshirts." This was a special militia loyal to Mussolini during the Fascist era. It was removed in 1943.

The Kings of Italy

The King of Italy was the official head of the country. But he shared power with the national parliament. The government actually answered to the parliament. The throne was passed down through the male line of the House of Savoy family.

The king became ruler at age 18. He promised to follow the constitution. His full title was "By the grace of God and by the will of the nation, King of Italy." From 1939 to 1943, he was also "King of Albania," and from 1936 to 1943, "Emperor of Ethiopia."

The king commanded the military, declared wars, and made peace treaties. He appointed people to state jobs and approved laws. Justice was done in his name, and he could pardon people.

| # | Image | Name (Dates) |

Period of rule | Monogram | Coats of arms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Begin | End | |||||

| 1 |  |

Victor Emmanuel II Father of the Fatherland (1820–1878) |

17 March 1861 |

9 January 1878 |

|

|

| 2 |  |

Umberto I the Good (1844–1900) |

9 January 1878 |

29 July 1900 |

|

|

| 3 |  |

Victor Emmanuel III the Soldier King (1869–1947) |

29 July 1900 |

9 May 1946 |

|

|

| 4 |  |

Umberto II the May King (1904–1983) |

9 May 1946 |

12 June 1946 |

|

|

National Symbols

The first coat of arms for the Kingdom of Italy came from the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont. It had the House of Savoy's coat of arms in the middle and four Italian flags from 1848.

Later, in 1870, two gold lions were added to hold the shield. A crowned knight's helmet was placed above it, with various royal orders around its collar. The lions held lances with the national flag. A royal cloak covered the coat of arms, and the Star of Italy was above it.

In 1890, the fur coat and lances were removed. The crown on the helmet was replaced by the Iron Crown of the Lombards. The whole design was under a canopy, topped with the Italian royal crown.

In 1929, Mussolini changed the two Savoy lions to lictor's bundles, which were symbols of the Fascist party. After he was removed from power in 1944, the older coat of arms from 1890 was brought back.

History of the Kingdom

How Italy Became One Country (1848–1870)

The Kingdom of Italy was born because Italian nationalists and monarchists wanted to unite the entire Italian Peninsula. After 1815, a movement called the Risorgimento (meaning "Rising Again") grew. Its goal was to unite Italy and free it from foreign control.

A key figure was Giuseppe Mazzini, who started the "Young Italy" movement. He wanted a united republic. Another famous leader was Giuseppe Garibaldi, a revolutionary general. He led the fight for unification in Southern Italy.

Meanwhile, the House of Savoy in the Kingdom of Sardinia also wanted a united Italy. Their government was led by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. In 1855, Sardinia joined Britain and France in the Crimean War, which helped Cavour gain respect from other powerful countries.

In 1859, Sardinia, with help from France, attacked the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence. This led to the freeing of Lombardy. Sardinia then gave Savoy and Nice to France.

In 1860–1861, Garibaldi led his forces to unite Naples and Sicily. At the same time, the House of Savoy's troops took over central Italy, except for Rome. On October 26, 1860, Garibaldi met Victor Emmanuel II and recognized him as King of Italy. Garibaldi gave up his dream of a republic for the sake of a united Italy under a king.

On March 17, 1861, the Kingdom of Italy was officially declared. Victor Emmanuel II became the first king. The capital moved from Turin to Florence.

In 1866, Italy allied with Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War. Even though Italy struggled in the war, Prussia's victory allowed Italy to gain Veneto.

The last piece of the puzzle was Rome. In 1870, France went to war with Prussia. France had to pull its troops out of Rome, who were protecting the Papal States. Italy took advantage of this and captured Rome. This completed Italy's unification, and Rome became the new capital.

After unification, Italy faced many challenges. The country lacked industry and good transportation. There was a lot of poverty, especially in the South, and many people couldn't read or write. Only a small number of wealthy people could vote.

Relations between Italy and the Vatican were bad for 60 years. The Popes saw themselves as "prisoners in the Vatican" and told Catholics not to vote. This "Roman question" was finally solved in 1929 with the Lateran Pacts.

Some Italian-speaking areas, like Trentino-Alto Adige and the Julian March, didn't join Italy until after World War I in 1918.

Bringing Different Systems Together

A big challenge for the new Italian government was combining the different political and administrative systems of the various regions. Each region had its own traditions.

The government worked to create a unified system for the army and navy. It also tried to standardize the different education systems across the country.

Italy's Economy and Growth

After unification, Italy created a new national currency, the Italian lira, in 1861. This helped to bring together the many different money systems used before.

From 1861 to 1940, Italy's economy grew a lot, even with some tough times and World War I. Unlike many countries where big companies led industrialization, Italy's growth came mostly from small and medium-sized family businesses.

At first, Italy was mostly an agricultural country, with most people working in farming. Technology helped increase exports of Italian farm products. As industry grew, fewer people worked in agriculture. However, farming in the South suffered from the hot, dry weather.

The government didn't focus much on agriculture at first, and it declined after 1873. Many farmers were poor and struggled to find enough food. Diseases like cholera spread quickly.

In the 1880s, Italy's wine industry faced problems when France recovered from its own wine issues. This led to job losses and bankruptcies in Italy.

Italy invested a lot in railways after 1860. The rail network grew rapidly. By 1914, Italy had about 17,000 km of railways.

During the Fascist era, huge amounts of money were spent on new technologies, especially for the military. Money also went to impressive projects like building the new ocean liner SS Rex, which set a speed record in 1933. The Macchi-Castoldi M.C.72 seaplane became the world's fastest in 1933. These projects showed off Italy's progress under the Fascists.

Industrial Growth in Italy

In the 1860s and 1870s, Italy's factories were small and old-fashioned. The country didn't have much coal or iron. In the 1880s, Italy started to industrialize more seriously. This period of growth lasted until 1912-1913.

Factories often set up near sources of hydropower (energy from water). Between 1887 and 1911, hydroelectricity became the main energy source, with over 60 power plants built. Industries like textiles, machinery, steel, iron, and chemicals grew quickly.

Important schools like the Politecnico (founded in 1863) and the Technical School for Engineers (founded in 1859) helped train people for these new industries.

Steel factories were built with government and private money. The ILVA group built the Bagnoli steel plant near Naples in 1904. In 1898, an engineer named Ernesto Stassano invented the Stassano furnace, an electric furnace, to make steel without needing foreign coal.

In 1899, the automobile industry began when Giovanni Agnelli founded Fiat. Another car factory, ALFA (later Alfa Romeo), was built in Milan in 1906. Car racing also became popular, with events like the Targa Florio in Sicily starting in 1906.

Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti (who served multiple terms between 1892 and 1914) focused on improving the economy. He worked to increase pensions and balance the government's budget. He also nationalized the railways and telephone system.

In 1906, the government lowered the national interest tax rate. This helped the state's finances and encouraged heavy industry to grow. The extra money allowed for big government projects, like completing the Simplon Tunnel in 1906. Many Italian workers helped build these large Alpine tunnels.

By 1911, about 55.4% of Italians worked in agriculture, and 26.9% worked in industry.

-

The Terni steel plant, established in 1884 (picture from 1912)

-

An advertisement for the 4HP automobile by FIAT in 1899

Social Changes and Emigration

Italy faced strong social problems. Its social laws were behind other European countries. Prime Minister Francesco Crispi funded colonial policies by raising taxes, which made people unhappy.

In 1898, there were big protests in Milan against rising bread prices. General Fiorenzo Bava-Beccaris ordered his troops to fire on the crowd, killing many people. King Umberto I praised the general, which made him unpopular. In 1900, an anarchist assassinated the king.

His successor was Victor Emmanuel III. But Giovanni Giolitti became the most powerful politician. He was Prime Minister several times between 1903 and 1914. This period is known as the Giolitti era. He tried to make changes that helped workers and encouraged industrialization.

Giolitti introduced state social insurance in 1912, similar to Germany's system. He also reformed voting rights, allowing more men to vote. Unemployment insurance was introduced in 1919.

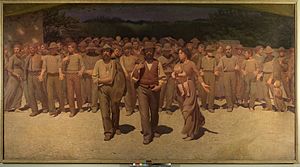

Workers formed unions and political parties. The Partito dei Lavoratori Italiani (Italian Workers' Party) was founded in 1892, later becoming the Partito Socialista Italiano (Italian Socialist Party).

| Measure | 1861 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1946 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population in millions | 22.182 | 25.766 | 28.437 | 30.947 | 32.475 | 34.565 | 37.837 | 40.703 | 43.787 | 45.380 |

Italy's population grew, but many people left the country. This was called mass emigration. By 1985, about 29 million people had left Italy. From 1876 to 1915, over 14 million people emigrated, mostly to North and South America.

The main reason for leaving was widespread poverty, especially among farmers. Many parts of Italy, especially the South and Northeast, were still rural and pre-modern. Farming conditions were very difficult.

The government at first tried to stop emigration, fearing a lack of workers. But then it allowed it, hoping to ease social tensions and financial problems.

The Southern Question and Italian Diaspora

Italy remained divided between rich elites and poor workers, especially in the South. Many southern farm workers were often unemployed. Peasants and small landowners in the South often revolted in the late 1800s.

This problem of the South's economic and social backwardness compared to the North was called the "Southern question". The South had poor transportation, low soil fertility, and high crime rates.

The unification of Italy ended the old feudal system in the South. But this didn't mean farmers got their own land. Many remained without property, and plots became smaller and less productive.

The first major wave of Italian emigration, known as the Italian diaspora, began around 1880. It lasted until the 1920s and early 1940s. Poverty and lack of land were the main reasons. Many Italians, especially from the South, left to find "work and bread" (Italian: pane e lavoro) in other countries.

Between 1860 and World War I, 9 million Italians left permanently. Most went to North or South America. Before 1900, most immigrants were from northern and central Italy. After that, more came from the South.

Italians who emigrated still felt a strong connection to their home country. Many donated money to build the Altare della Patria monument in Rome. A plaque there says "Italians abroad to the Motherland," symbolizing their lasting bond.

Education in the Kingdom

Italy created a state school system in 1859 with the Legge Casati (Casati Act). This law made primary education (scuola elementare) compulsory, meaning children had to go to school. Its goal was to increase literacy (the ability to read and write).

However, in rural and southern areas, many children still didn't go to school. The illiteracy rate was nearly 80% in 1861, and it took over 50 years to cut it in half.

Another important law was the Legge Gentile in 1923, during Mussolini's Fascist rule. This law raised the compulsory school age to 14. It created different school paths: one for higher education and another for quick job training. It also made the Catholic religion a central part of education.

The Liberal Era (1870–1914)

After unification, Italy's politics were mostly liberal. The liberal-conservative right (destra storica) was in power at first.

Agostino Depretis and Trasformismo

In 1876, Agostino Depretis became Prime Minister. He started a long period known as the Liberal Period. This time was known for corruption, unstable governments, continued poverty in Southern Italy, and the government using strong, sometimes unfair, methods.

Depretis used a political idea called trasformismo ("transformism"). In theory, this meant choosing good politicians from different groups for the government. But in practice, Depretis used it to pressure districts to vote for his candidates. This helped him stay in power, especially in Southern Italy.

Depretis also took strong actions, like banning public meetings and sending "dangerous" people to remote islands. But he also passed liberal laws, such as making elementary education free and compulsory and ending required religious teaching in schools.

In 1887, Francesco Crispi became prime minister. He focused on foreign policy, wanting to make Italy a great world power. He increased military spending and tried to gain favor with Germany. Italy joined the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882. This alliance lasted until 1915.

Crispi was authoritarian, meaning he ruled with a strong hand. But he also passed liberal laws, like the Public Health Act of 1888.

Italian Colonialism

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Italy, like other European powers, tried to get colonies, especially in Africa. Italy was not as strong as Britain, France, or Germany, and faced resistance.

The government pursued colonial projects to gain support from Italian nationalists who wanted to rebuild a new Roman Empire. Italy already had many people living in cities like Alexandria and Tunis.

Colonialism began in 1885 when Italy sent soldiers to Massawa in East Africa. In 1888, Italy took Massawa by force, creating the colony of Italian Eritrea. Italy also took land on the southern side of the Horn of Africa, which became Italian Somaliland.

In 1889, Italy signed the Treaty of Wuchale with Ethiopia. The Italian version of the treaty said Ethiopia would become an Italian protectorate, but the Ethiopian version said Ethiopia could choose to use Italy for foreign affairs. When this difference was discovered, Ethiopia's Emperor Menelik II ended the treaty in 1895.

Italy decided to use military force, leading to the First Italo-Ethiopian War. However, the Italian army was defeated by the large Ethiopian army at the Battle of Adwa. Italy was forced to retreat. The war ended with the Treaty of Addis Ababa in 1896, which recognized Ethiopia as an independent country.

From 1899 to 1901, Italy joined other countries in fighting the Boxer Rebellion in China. In 1901, China gave Italy a small area in Tianjin.

In 1911, Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire and invaded Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica. These areas became Libya. The war ended a year later. The annexation of Libya made nationalists want Italy to control the Mediterranean Sea.

Giovanni Giolitti's Influence

Giovanni Giolitti became Prime Minister in 1892. He returned to lead Italy from 1903 to 1914. He was the first long-term Prime Minister because he was skilled at using trasformismo to gain support.

During Giolitti's time, voting fraud was common. He tried to improve voting in areas that supported him, while trying to control areas that opposed him. Southern Italy remained in very poor condition. Many southern Italians could not read or write, and there was much poverty and crime. Giolitti himself admitted that in some places, "the law does not operate at all."

In 1911, Giolitti's government sent forces to occupy Libya. The success of the Libyan War made nationalists happy. Italy was the first country to use airships for military purposes and conducted aerial bombing on Ottoman forces.

The war made the Italian Socialist Party more radical. Giolitti resigned in March 1914. The era of liberalism in Italy was effectively over.

World War I and the End of the Liberal State (1915–1922)

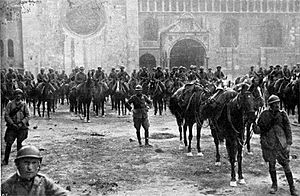

Italy entered World War I in 1915 to complete its national unity. This is why Italy's involvement in World War I is sometimes called the "Fourth Italian War of Independence".

For six months, Italy stayed neutral because the Triple Alliance was only for defensive purposes. Italy's leaders secretly negotiated with both sides to get the best deal. They got a good offer from the Entente (Allies), who promised Italy large parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including Tyrol and Trieste.

When the Treaty of London was announced in May 1915, many people were upset. Most Italians feared war and didn't care much about gaining new land. Farmers saw war as a disaster. Businesses were also against it, fearing government controls and taxes.

Benito Mussolini started a newspaper called Il Popolo d'Italia, which at first tried to convince socialists to support the war. The Allied Powers helped fund the newspaper. Later, this newspaper became the official paper of the Fascist movement.

Italy entered the war with 875,000 soldiers, but the army was poorly led and lacked modern weapons. Italy struggled in the war, which was fought on a narrow front along the Isonzo River. In 1916, Italy declared war on Germany, which helped Austria. About 650,000 Italian soldiers died, and 950,000 were wounded.

The Italian victory was announced by the Bollettino della Vittoria. This marked the end of the war on the Italian Front and helped lead to the end of World War I less than two weeks later.

After the war, Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando met with other world leaders to discuss new borders for Europe. Italy gained little land, as U.S. President Woodrow Wilson wanted all European nationalities to form their own nations. The Treaty of Versailles did not give Italy Dalmatia or Albania, as promised. Italy also didn't get any German colonies.

Despite this, Orlando signed the treaty, which caused anger in Italy. The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919) and the Treaty of Rapallo (1920) allowed Italy to annex Trentino Alto-Adige, the Julian March, Istria, and the city of Zara.

Many Italians were furious about the peace settlement. The nationalist poet Gabriele D'Annunzio led war veterans to take over the city of Fiume in September 1919. He was called Il Duce ("The Leader") and used black-shirted fighters. These ideas and symbols were later adopted by Benito Mussolini's Fascist movement.

Italy's lack of territorial gains led to the outcome being called a mutilated victory. This idea was used by Mussolini to fuel Italian imperialism and gain support for Fascism.

Fascist Rule, World War II, and Civil War (1922–1946)

The Rise of Fascism

Benito Mussolini created the Fasci di Combattimento (Combat League) in 1919. It was made up of patriotic veterans who opposed the Italian Socialist Party. At first, this Fascist movement had some left-leaning ideas, like promising social revolution and women's voting rights.

After World War I, Italy faced economic problems and political instability. In October 1922, Mussolini used a general strike to demand political power for the Fascist Party. If not, he threatened a coup. A group of 30,000 Fascists marched to Rome (the March on Rome), claiming they would restore order.

King Victor Emmanuel III had to choose between Mussolini's Fascists and the socialist party. He chose the Fascists.

Mussolini formed a government with nationalists and liberals. In 1923, he passed the Acerbo Law, which gave two-thirds of the parliament seats to the party that got at least 25% of the votes. The Fascist Party used violence to win the 1924 election. Socialist leader Giacomo Matteotti was murdered after he spoke out against the Fascist violence.

Over the next four years, Mussolini took away almost all checks on his power. In 1925, a law made him responsible only to the king. Local governments were replaced by appointed officials. By 1928, all other political parties were banned.

Ending the Roman Question

During Italy's unification in the mid-1800s, the Papal States (lands ruled by the Pope) resisted joining the new nation. Italy invaded and took over most of the Papal States, including Rome, by 1870. For 60 years, relations between the Pope and the Italian government were hostile. This was known as the "Roman question".

The Lateran Treaty was signed on February 11, 1929, between the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy See (the Pope's government). This treaty solved the "Roman question." It recognized Vatican City as an independent state ruled by the Holy See. Italy also agreed to pay the Roman Catholic Church for the loss of the Papal States.

Foreign Policy Under Fascism

Mussolini's foreign policy had three main goals:

- Continue Italy's earlier goals in the Balkans and North Africa.

- Address the disappointment after World War I, where Italy felt it didn't gain enough.

- Restore the pride and glory of the Roman Empire.

Italian Fascism was based on Italian nationalism. It wanted to complete the Risorgimento by bringing "unredeemed Italy" into the country. This included areas like Dalmatia, Malta, Corfu, Italian Switzerland, Corsica, Nice, and Savoy.

Mussolini promised to make Italy a great power again, building a "New Roman Empire" and controlling the Mediterranean Sea. Fascist propaganda used the Latin phrase "Mare Nostrum" ("Our Sea") to describe the Mediterranean.

In 1923, Italy briefly occupied the Greek island of Corfu. In 1925, Albania came under strong Italian influence. Italy had bad relations with Yugoslavia because it still claimed Dalmatia.

During the Spanish Civil War, Italy sent weapons and over 60,000 troops to help the Nationalist side led by Francisco Franco. This gave Italy better access to Spanish ports and increased its influence in the Mediterranean. Italy also built up its navy, making it the fourth largest in the world by 1940.

Mussolini and Adolf Hitler first met in 1934. Publicly, they showed a close relationship, but privately, they were suspicious of each other. Mussolini initially opposed German plans to annex Austria. However, due to concerns about German expansion, Italy joined the Stresa Front with France and the UK in 1935.

In 1935, Mussolini decided to invade Ethiopia. This Second Italo-Ethiopian War isolated Italy internationally. Only Nazi Germany supported Italy's actions. After being criticized by the League of Nations, Italy left the League in 1937. Mussolini then had to align more closely with Hitler. He reluctantly stopped supporting Austrian independence, and Hitler annexed Austria in 1938. Mussolini also supported Germany's claims on Sudetenland at the Munich Conference. In 1938, influenced by Hitler, Mussolini supported anti-Jewish laws in Italy. After Germany took over Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Italy invaded Albania and made it a protectorate.

As war approached in 1939, Italy started a strong media campaign against France, claiming Italians living there were being mistreated. In May 1939, Italy signed a formal alliance with Germany called the Pact of Steel. Mussolini felt he had to sign it, even though he worried Italy wasn't ready for war.

World War II and the Fall of Fascism

When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, starting World War II, Mussolini chose to stay neutral at first, but still supported Hitler. Mussolini and the Fascist government planned to annex large parts of Africa and the Middle East. However, the King and military leaders warned Mussolini that Italy lacked enough tanks, armored vehicles, and aircraft for a long war.

Italy entered the war on June 10, 1940. Mussolini hoped to quickly take French territories like Savoy, Nice, Corsica, Tunisia, and Algeria. But Germany signed an armistice with France, which kept control of southern France and its colonies. This angered the Fascist government.

In summer 1940, Mussolini ordered the bombing of Mandatory Palestine and the conquest of British Somaliland. In September, he ordered the invasion of Egypt. Despite early success, Italian forces were pushed back by the British. Hitler had to send his Afrika Korps to help.

On October 28, Mussolini attacked Greece. The Greeks fought back successfully and pushed the Italians into Albania. Hitler had to help Mussolini again by attacking Greece through the Balkans. This led to the breakup of Yugoslavia and Greece's defeat. Italy gained parts of Slovenia, Dalmatia, Montenegro, and set up puppet states in Croatia and Greece.

By 1942, Italy was struggling. Its economy couldn't handle the war, and Italian cities were heavily bombed by the Allies. The campaign in North Africa also began to fail in late 1942, especially after the defeat at El Alamein.

By 1943, Italy was losing on all fronts. Half of its forces fighting in the Soviet Union were destroyed. The African campaign failed, and the Balkans remained unstable. Italians wanted the war to end. In July 1943, the Allies invaded Sicily. On July 25, Mussolini was removed from power and arrested by order of King Victor Emmanuel III. General Pietro Badoglio became the new Prime Minister. Badoglio banned the National Fascist Party and signed an armistice with the Allies.

Civil War and Liberation

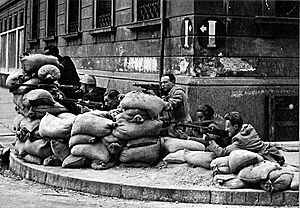

Soon after being removed, Mussolini was rescued by German commandos. The Germans took Mussolini to northern Italy, where he set up a Fascist puppet state called the Italian Social Republic (RSI). Meanwhile, the Allies advanced in southern Italy. In September 1943, Naples rose up against the German forces.

The Allies organized some royalist Italian troops into the Italian Co-Belligerent Army. Other Italian troops continued to fight with Nazi Germany in the National Republican Army. A large Italian resistance movement started a long guerrilla war against German and Fascist forces.

The Germans, often helped by Fascists, committed many atrocities against Italian civilians. The Kingdom of Italy declared war on Nazi Germany on October 13, 1943.

On June 4, 1944, the German occupation of Rome ended as the Allies advanced. The final Allied victory in Italy came in spring 1945. German and Fascist forces in Italy surrendered on May 2, shortly before Germany surrendered, ending World War II in Europe on May 8.

On April 25, 1945, the National Liberation Committee for Northern Italy called for a general uprising against the Nazis. This day is now celebrated as Liberation Day in Italy.

Mussolini was captured on April 27, 1945, by communist Italian partisans near the Swiss border. He was executed the next day for treason. On May 2, 1945, German forces in Italy surrendered.

After Mussolini's fall, several prime ministers led Italy. Finally, Alcide De Gasperi oversaw the change to a Republic after King Victor Emmanuel III stepped down.

Anti-Fascism Against Mussolini

Mussolini's Fascist government used the term anti-fascist to describe its opponents. His secret police was called the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism (OVRA). In the 1920s, anti-fascists, many from labor movements, fought against Mussolini's violent Blackshirts.

Some workers formed a group called Arditi del Popolo because they disagreed with their unions making peace with Mussolini. The Italian anarchist Severino Di Giovanni organized bombings against Italian Fascists in Argentina. The Italian liberal anti-fascist Benedetto Croce wrote his Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals in 1925.

The Concentrazione Antifascista Italiana (Italian Anti-Fascist Concentration) was a group of anti-fascist organizations that worked together from 1927 to 1934. They tried to coordinate actions from outside Italy to fight fascism.

Giustizia e Libertà (Justice and Freedom) was another important anti-fascist group, active from 1929 to 1945. They believed in actively opposing fascism.

Between 1920 and 1943, many anti-fascist movements were active among Slovenes and Croats in areas Italy had annexed after World War I. The group TIGR carried out sabotage and attacks against Fascist officials.

Many members of the Italian resistance went to the mountains to fight against Italian Fascists and German Nazi soldiers during the Italian Civil War. Several Italian cities, like Turin, Naples, and Milan, were freed by anti-fascist uprisings.

The End of the Kingdom (1946)

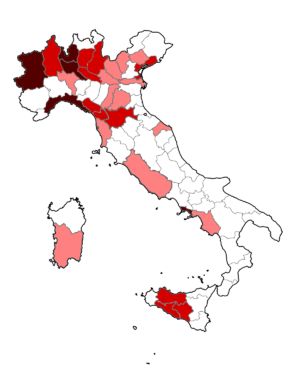

The 1946 Referendum

After World War II, Italy's economy was destroyed, and society was divided. Many people were angry at the monarchy for supporting the Fascist regime for 20 years.

Even before the Fascists, the monarchy was seen as not doing well. World War I was also seen as a reason for Fascism's rise. These frustrations led to a renewed push for a republic. In 1944, it was clear that King Victor Emmanuel III was too linked to Mussolini to continue ruling. He gave his powers to his son, Crown Prince Umberto.

Victor Emmanuel III remained King in name until just before the 1946 Italian institutional referendum. This vote was to decide if Italy should remain a monarchy or become a republic. On May 9, 1946, he stepped down, and his son became King Umberto II.

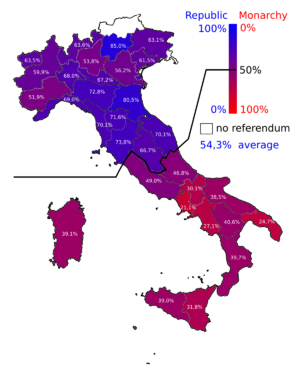

However, on June 2, 1946, the republican side won with 54% of the votes. Italy officially became a republic. This day is now celebrated as Festa della Repubblica (Republic Day). This was also the first time Italian women voted in a national election.

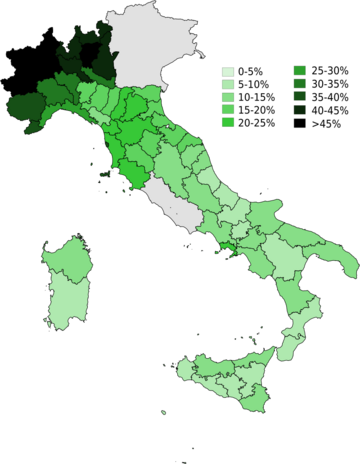

The results showed a clear split: the North voted for the republic (66.2%), and the South voted for the monarchy (63.8%). Some monarchists claimed the vote was unfair.

Umberto II decided to leave Italy on June 13 to prevent fights between monarchists and republicans. He went into exile in Portugal. From 1948, male descendants of Umberto II were banned from entering Italy, but this rule was removed in 2002.

What Happened Next

The Republican Constitution was approved on January 1, 1948. It was created by a group of anti-fascist leaders who helped defeat the Nazis and Fascists.

Under the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947, Italy lost Istria, Kvarner, most of the Julian March, and the city of Zara to Yugoslavia. This led to many local Italians leaving their homes. Italy also lost all its colonies, ending the Italian Empire. The current Italian border has been in place since 1975.

Fears of a possible Communist takeover were important in the first general election in 1948. The Christian Democrats, led by Alcide De Gasperi, won by a lot. In 1949, Italy joined NATO.

The Marshall Plan helped Italy's economy recover. Until the late 1960s, Italy experienced strong economic growth, known as the "Economic Miracle". In the 1950s, Italy became one of the six founding countries of the European Communities, which later became the European Union.

Maps of Italy's Growth

-

The Italian States in 1859, before the Second Italian War of Independence.

-

The Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860, after gaining Lombardy.

-

The Kingdom of Italy in 1861, after the Expedition of the Thousand.

-

The Kingdom of Italy in 1924, after World War I, including new areas like Tridentina and Giulia.

-

The Kingdom of Italy at its largest in 1943, during World War II, with annexed territories from France and Yugoslavia.

- Legend

- Kingdom of Sardinia (Kingdom of Italy from 1861)

- Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

- Papal States

- Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia

|

Changes to Italy's Coat of Arms

See Also

In Spanish: Reino de Italia (1861-1946) para niños

In Spanish: Reino de Italia (1861-1946) para niños

- Unification of Italy

- Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy

- History of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

- House of Savoy

- List of prime ministers of Italy

- Military history of Italy during World War I

- Military history of Italy during World War II

- Roman question

- Italian Empire

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |