Battle of Vittorio Veneto facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Vittorio Veneto |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian Front of World War I | |||||||

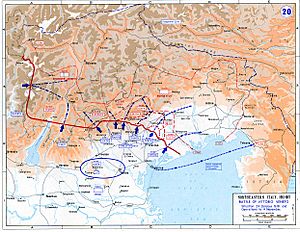

Map of the battle |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

57 divisions:

Total : 1,486,200 7,700 guns600 aircraft |

61 divisions:

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

40,917

|

528,000 30,000 killed 50,000 wounded 448,000 captured 5,000+ artillery pieces captured |

||||||

The Battle of Vittorio Veneto was a very important battle fought during World War I. It took place near the city of Vittorio Veneto in Italy, from October 24 to November 3, 1918. This battle was a huge victory for the Italian army and its allies.

It happened after the Italian army had already stopped the Austro-Hungarian forces in the Battle of the Piave River. The victory at Vittorio Veneto marked the end of the war on the Italian Front. It also led to the complete collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and helped bring World War I to an end just one week later.

During the battle, the Italian forces captured over 5,000 artillery guns and more than 350,000 Austro-Hungarian soldiers. These captured soldiers came from many different groups, including Germans, Czechs, Slovaks, South Slavs, Poles, Romanians, Ukrainians, and even some Italians who were loyal to Austria-Hungary.

Contents

What's in a Name?

When this big battle happened in November 1918, the nearby city was simply called Vittorio. It was named in 1866 after Vittorio Emanuele II, who was the first king of the newly formed Kingdom of Italy.

People usually called the battle the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. This meant "Vittorio in the Veneto region" of Italy. A few years later, in July 1923, the city's name was officially changed to Vittorio Veneto.

How the Battle Started

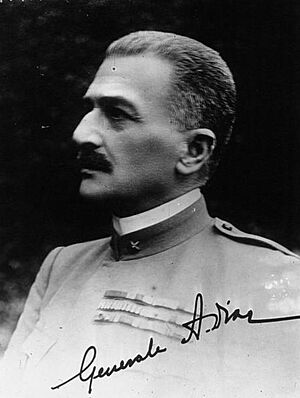

Before this battle, the Italian Army faced a tough time in the Battle of Caporetto in late 1917. They lost many soldiers and had to retreat. Because of this, the Italian commander, Luigi Cadorna, was replaced by General Armando Diaz.

General Diaz was very good at organizing the troops. He set up a strong defense line along the Piave River. He used a strategy called "defense in depth," which meant having layers of defenses and mobile groups of soldiers ready to move where needed. This helped stop the enemy's advance.

In June 1918, the Austro-Hungarian army tried a big attack to break through the Piave River line. This attack was called the Battle of the Piave River. But the Austro-Hungarians lost badly, with many soldiers killed, wounded, or captured.

After this victory, General Diaz waited for the right moment to attack. He wanted to be sure of success. His plan was for three of his five armies to cross the Piave River and push towards Vittorio Veneto. The goal was to cut off the supply lines of the two Austrian armies they were fighting.

The Allied forces had a total of 57 infantry divisions. This included 52 Italian divisions, three British, two French, and one American regiment. The Austro-Hungarian army had 46 infantry divisions and six cavalry divisions. Both sides were also dealing with the flu and malaria, which made many soldiers sick. The Allies had more artillery guns, about 7,700 compared to Austria-Hungary's 6,000.

The Italian armies in the mountains were told to hold their positions and follow the enemy if they retreated. The toughest job, attacking the strongest enemy spots, went to the Fourth Army. Other armies, like the Twelfth Army (with French and Italian soldiers) and the Tenth Army (with British and Italian soldiers), were to cross the Piave River. The Third Army was to hold the lower Piave and cross when the enemy weakened. A Ninth Army, with Italian, Czechoslovak, and American soldiers, was kept in reserve. The Allies also had 600 aircraft, which helped them control the skies.

The Battle Begins

On the night of October 23, the battle started. Soldiers from the British 7th Division and Italian 11th Corps tried to cross the Piave River. They aimed to take a large island called Grave di Papadopoli. Italian engineers helped row the British soldiers across the river in the dark and mist. The British soldiers used their bayonets quietly to surprise the enemy. They quickly took their part of the island. Even though the Italians faced heavy machine-gun fire, the Austrians gave up the island by morning.

In the early hours of October 24, exactly one year after the Battle of Caporetto, the main attack began. The Italian Fourth Army started a huge artillery bombardment on Monte Grappa. This was meant to draw in the Austro-Hungarian reserve troops. The Italian infantry then began to climb the steep mountainsides.

The Piave River was flooded, which made it hard for some armies to advance at the same time. But the Tenth Army, led by Earl Cavan, managed to cross the river on October 27. By evening, the Allies had advanced quite a bit. The Italian Tenth Army held its ground, creating a strong position about 2.5 miles deep and 5 miles wide. The British captured 3,520 prisoners and 54 guns.

The Austro-Hungarian commander, Svetozar Boroević von Bojna, ordered a counter-attack. But his soldiers refused to obey. This was a big problem for the Austrians from then on, and the counter-attack failed. The first few days of the battle involved intense artillery fights, with both sides firing millions of shells.

Austria-Hungary Falls Apart

On October 28, things changed dramatically for Austria-Hungary. Groups representing different parts of the empire started declaring their independence. First, the Czechs declared Bohemia's independence. The next day, South Slavs (who would later form Yugoslavia) also declared independence. On October 31, the Hungarian Parliament announced they were leaving the union with Austria. This officially broke up the Austro-Hungarian state.

Because of these political changes and the ongoing military problems, the Austro-Hungarian high command ordered a general retreat on October 28.

On October 29, the Italian Eighth Army pushed forward towards Vittorio Veneto. Their fast-moving cavalry and bicycle soldiers entered the city on the morning of October 30. The Italian Third Army also crossed the lower Piave. Scouts in the mountains found that the Austrians were pulling back there too. More Allied troops, including the 332nd US Infantry Regiment, crossed the Piave behind the Italian Tenth Army.

Vittorio Veneto was fully captured the next day by the Italian Eighth Army. They continued to push towards the Tagliamento river. Trieste was taken by Italian forces arriving by sea on November 3.

To communicate across the flooded Piave River, the Italian Eighth Army used special swimmers from an elite unit called the Arditi Corps, known as the Caimani del Piave ("Caimans of the Piave"). These brave soldiers were trained to stay in the cold, strong river currents for many hours. They carried knives and grenades. Many of them died in the river during the campaign. The Italian Twelfth Army, led by French General Jean Graziani, also kept advancing.

On the morning of October 31, the Italian Fourth Army attacked again on Monte Grappa. This time, they managed to push past the old Austrian positions towards Feltre. In both the mountains and the plains, the Allied armies kept pushing until an armistice (a ceasefire agreement) was made.

Austria-Hungary suffered huge losses: about 30,000 killed and wounded, and 300,000 prisoners. The Italians had 37,461 casualties (dead and wounded) during the 10-day battle, with many of those on Monte Grappa. The British lost 2,139 soldiers, and the French lost 778.

The Armistice of Villa Giusti was signed on November 3 at 3:20 PM. It was set to officially start 24 hours later, at 3:00 PM on November 4.

What Happened Next

The Austrian command told its troops to stop fighting on November 3. After the armistice was signed, Austrian General Weber told the Italians that his army had already put down their weapons. He asked them to stop fighting immediately and not advance further. But the Italian General Badoglio refused, threatening to continue the war. Even before the official ceasefire, the Austro-Hungarian army was already falling apart and retreating in chaos.

Italian troops continued to advance until 3:00 PM on November 4, when the armistice officially began. By the end of November, Italian forces had occupied all of Tyrol, including Innsbruck.

The terms of the armistice were very strict for Austria-Hungary. Their forces had to leave all the land they had occupied since August 1914. They also had to give up areas like South Tirol, Trieste, and Dalmatia. All German forces had to leave Austria-Hungary within 15 days or be held as prisoners. The Allies were also allowed to use Austria-Hungary's roads and railways to reach Germany from the south.

This battle marked the end of World War I on the Italian front. It also led to the complete breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As mentioned, Hungary officially left its union with Austria on October 31. Other parts of the empire also declared their independence. The surrender of Austria-Hungary, Germany's main ally, was a big reason why Germany decided it could no longer continue the war. Just a week after the Austro-Hungarians, the Germans also asked for an armistice.

Why This Battle Was Important

Some important figures from World War I talked about how important the Battle of Vittorio Veneto was.

Erich Ludendorff, a top German general, said that the battle caused the Austro-Hungarian Empire to collapse, and this "dragged Germany in its fall." This means he believed the loss of Austria-Hungary was a major blow to Germany.

However, German historian Ernst Nolte had a different view. He said that Vittorio Veneto was just "an encounter which had merely given the coup de grace to the abandoned army of an already crumbling state." This means he thought the Austro-Hungarian Empire was already falling apart, and the battle was just the final push that finished it off.

Gallery

-

Italian cavalry reaches Trento on 3 November 1918

See also

- Bollettino della Vittoria

- Battle of the Piave River