Spanish flu facts for kids

|

|

| Disease | Influenza |

|---|---|

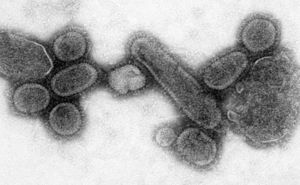

| Virus strain | Strains of A/H1N1 |

| Location | Worldwide |

| Date | February 1918 – April 1920 |

| Suspected cases‡ | 500 million (estimated) |

|

Deaths

|

25–50 million (generally accepted), other estimates range from 17 to 100 million |

| ‡ Suspected cases have not been confirmed as being due to this strain by laboratory tests, although some other strains may have been ruled out. | |

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or the Spanish flu, was a very serious worldwide flu outbreak. It was caused by a type of flu virus called H1N1. The first known case was in March 1918 in Kansas, USA. Other cases appeared in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom soon after.

Over two years, about one-third of the world's population, around 500 million people, got sick. Between 17 million and 100 million people died, making it one of the deadliest pandemics ever.

The pandemic happened near the end of World War I. Countries fighting in the war kept news about the flu quiet to keep people's spirits up. But newspapers in neutral Spain reported it freely. This made it seem like Spain was where the flu started, leading to the name "Spanish flu," even though it wasn't. Scientists still aren't sure exactly where it began.

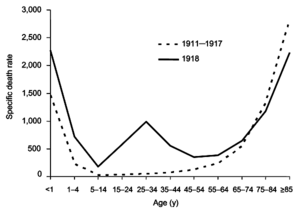

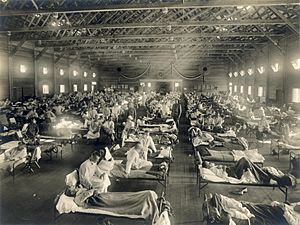

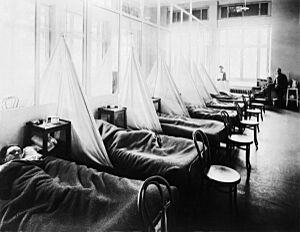

Usually, flu mostly affects very young children and older people. But this flu was different; many young adults also got very sick and died. Poor nutrition, crowded hospitals, and bad hygiene during the war made things worse. Many people died from other infections that attacked their weakened bodies.

Contents

Understanding the Spanish Flu

Why So Many Names?

This flu outbreak had many different names around the world. People didn't know much about viruses back then. Doctors were confused. One newspaper even suggested calling it "Man hu," which means "What is it?" in ancient Hebrew.

Descriptive Names for the Flu

Early on, doctors noticed that some very sick patients turned blue-violet. This was because they weren't getting enough oxygen. People called this the 'purple death'.

Outbreaks in military hospitals in France and England in 1916–17 showed similar symptoms. Doctors called it 'three-day fever' in some places because symptoms often lasted about three days.

How the "Spanish Flu" Name Started

The name 'Spanish influenza' became popular outside Spain. This was because countries fighting in World War I didn't want to report bad news. They censored their newspapers to keep up public morale.

Spain was a neutral country, so its newspapers reported freely about the flu. This made it seem like the flu started there, even though it didn't. Spanish officials were surprised and protested this name.

Other Names Around the World

People often blamed outsiders for diseases. The French press first called it 'American flu'. British soldiers called it 'Flanders flu', and German soldiers called it 'Flemish fever'. These names came from a battlefield in Belgium.

In Senegal, it was 'Brazilian flu', and in Brazil, 'German flu'. In Spain, it was also known as 'French flu'. The World Health Organization now advises against naming diseases after places or groups of people. This helps prevent unfair blame or stigma.

Local Names and a Children's Rhyme

Some local names described the flu's effects. For example, in some African languages, it meant "disease from seeking profit in wartime" or "disease which passes through like a bullet."

A children's skipping-rope rhyme from an earlier flu outbreak was changed for this pandemic:

I had a little bird,

its name was Enza.

I opened the window,

and in-flu-enza.

The Flu's Journey: Where Did It Begin?

Scientists still debate where the Spanish flu started. There are a few main ideas.

Theories on the Flu's Origin

United States

Some historians believe the flu started in Kansas, USA. The first confirmed cases were recorded there in March 1918. However, some studies suggest these early cases were milder than later ones. This makes it less likely to be the very first origin.

Europe

Another idea is that the flu began in military camps in France. These camps were very crowded. They also had pigs and poultry, which can carry flu viruses. A virus from birds might have changed and then spread to pigs, and then to humans. Some reports suggest a similar illness was seen in Europe as early as 1916.

China

Some researchers think the flu might have come from China. In 1917, a respiratory illness affected Chinese laborers who were sent to Europe for the war. Chinese health officials later thought this illness was the same as the Spanish flu. However, other studies found that Chinese workers in Europe had low death rates from the flu. This makes it less likely they were the original source.

The Flu's Path: A Timeline of Waves

The Spanish flu spread in several waves across the world.

First Wave: Early 1918

The pandemic officially began on March 4, 1918, at a military camp in Kansas. But cases were seen in Haskell County, Kansas, even earlier. As the U.S. joined World War I, soldiers carried the disease to other camps and then to Europe.

This first wave was relatively mild. The number of deaths was not much higher than a typical flu season. However, it still caused problems for military operations. Many soldiers in France, Britain, and Germany got sick.

Deadly Second Wave: Late 1918

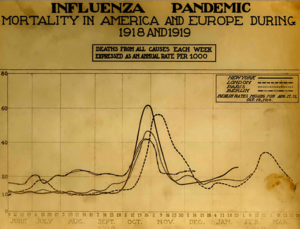

The second wave started in August 1918 and was much more severe. It likely spread from Brest, France, to places like Boston, USA, and Freetown, Sierra Leone, by ships. Troop movements helped it spread quickly across North and South America.

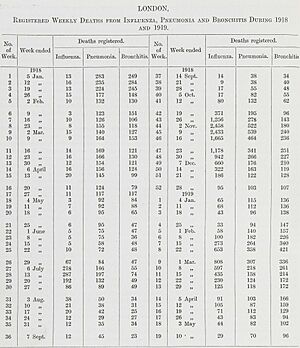

This wave was the deadliest. October 1918 had the highest number of deaths during the entire pandemic. For example, a parade in Philadelphia in September 1918 led to 12,000 deaths. The flu spread through Russia, Asia, and Africa. By December, this wave was mostly over.

Third Wave: 1919

The flu continued to cause outbreaks in 1919, especially during the winter in the Northern Hemisphere. Some U.S. cities saw cases rise again in late 1918. Many places brought back rules like closing schools and banning large gatherings.

Europe also experienced a significant third wave, peaking in early 1919. Australia, which had avoided the flu in 1918 due to strict quarantines, saw its first cases in January 1919. Other parts of the world, like Madagascar and South America, also had new outbreaks.

Fourth Wave: 1920

In late 1919 and early 1920, some areas saw another return of the flu. Japan experienced a rapid outbreak in December, leading to renewed health measures like mask-wearing.

In the United States, major outbreaks occurred in cities like Chicago and New York City in early 1920. While this wave was often milder than the deadly second wave, it still caused many deaths. Some cities, like Detroit and Milwaukee, had higher death rates in 1920 than in all of 1918.

After the Pandemic: Seasonal Flu

By mid-1920, people and governments generally considered the pandemic to be over. The H1N1 virus became a regular seasonal flu. In 1957, a new flu virus (H2N2) replaced H1N1. Later, in 1977, a version of the old H1N1 virus reappeared, mainly affecting younger people. Today, different flu viruses continue to circulate.

How the Flu Spread and Affected Bodies

How the Virus Spread and Changed

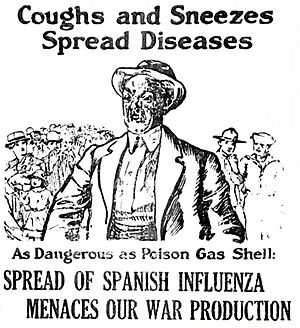

The flu spread easily from person to person. The crowded conditions and massive movement of soldiers during World War I helped the virus spread quickly. The war also might have made people's immune systems weaker. This made them more likely to get sick.

Normally, milder viruses spread more easily because sick people stay home. But in the war, severely ill soldiers were moved to crowded hospitals. This helped the deadlier virus spread.

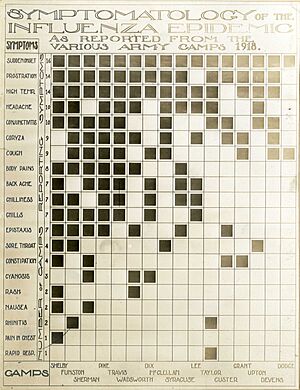

What Were the Symptoms?

Most people had typical flu symptoms like a sore throat, headache, and fever. But during the second wave, the disease became much more serious. Many people developed severe lung infections, which often led to death.

In these serious cases, people's skin would turn blue or purple. This was a sign that their lungs were filling with fluid, and they weren't getting enough oxygen. Other symptoms included bleeding from the nose and mouth, and for pregnant women, it often led to serious problems.

Scientists later found that the virus caused the body's immune system to overreact. This strong reaction, called a "cytokine storm," was especially harmful to young, healthy adults. Their strong immune systems attacked their own bodies, causing more damage.

Why It Was Hard to Diagnose

At the time, viruses were too small to see with microscopes. Doctors mistakenly thought a bacterium, Haemophilus influenzae, was the cause. They developed a vaccine against this bacterium, which helped with secondary infections but didn't stop the flu virus itself.

During the deadly second wave, people also worried it might be other diseases like plague or cholera. Some even believed it was caused by "noxious gases" or that enemies had poisoned medicines.

Weather's Role in the Pandemic

Studies suggest that cold and wet weather during the pandemic might have weakened people's immune systems. This was especially true for soldiers exposed to harsh conditions during the war. Increased rain and lower temperatures could have helped the virus spread and made people more vulnerable.

How People Responded to the Flu

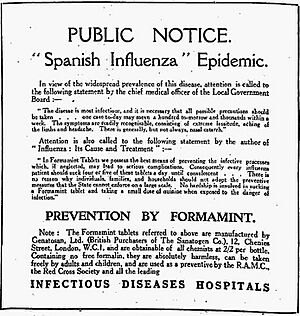

Public Health Actions

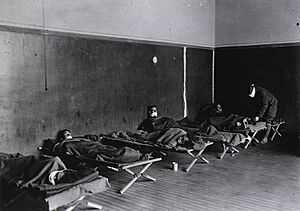

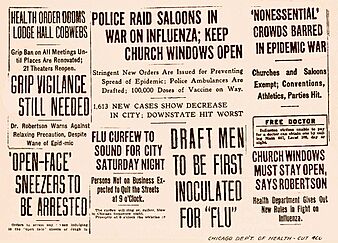

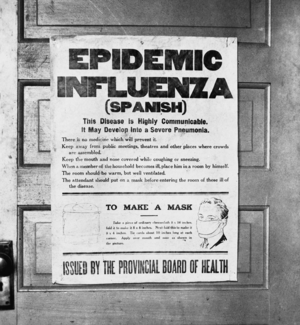

Governments and health officials took action, though sometimes slowly. Islands like Iceland and Australia used strict quarantines to protect their populations. Many places introduced social distancing measures. They closed schools, theaters, and churches. They also limited public transportation and banned large gatherings.

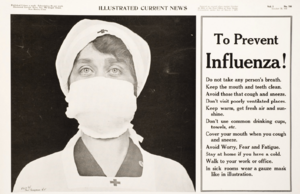

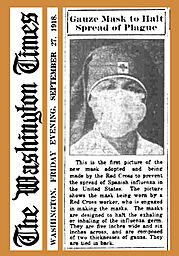

Wearing face masks became common in some areas, like Japan and parts of the U.S. However, some people resisted wearing them. Vaccines were developed, but they targeted bacteria, not the flu virus itself. So, they only helped with secondary infections.

Medical Treatments

Since there were no antiviral medicines for the flu virus or antibiotics for bacterial infections, doctors used various treatments. These included medicines like aspirin, quinine, and arsenic. Old traditional treatments, like bloodletting, were also sometimes used.

Spreading Information (and Misinformation)

During World War I, many countries censored news about the pandemic. They didn't want to cause panic. This meant people often didn't get accurate information. Misinformation also spread. Some people believed the flu was caused by poison gas or that enemies were behind it.

The Flu's Deadly Impact

The Spanish flu infected about 500 million people, which was about one-third of the world's population. It is considered one of the deadliest pandemics in history. Estimates of deaths range from 17 million to 100 million people worldwide.

Unlike typical flu outbreaks, this pandemic mostly killed young adults. In 1918–1919, nearly half of all deaths in the U.S. were among young adults aged 20 to 40. This was unusual because flu usually affects very young children and older people the most. Older adults might have had some protection from an earlier flu outbreak in 1889–1890. Pregnant women were especially vulnerable.

Death rates varied greatly around the world. Some parts of Asia and Africa had much higher death rates than Europe and North America. Cities were generally affected worse than rural areas.

There were also differences between social groups. In some cities, poorer people living in smaller, more crowded apartments died at a higher rate. Newcomers to countries also faced higher risks. More men died than women in many places, possibly because men were more likely to be exposed outside the home. However, in India, more women died, perhaps due to poorer nutrition and their role in caring for the sick.

Communities Hit Hard

Even in places with lower death rates, so many adults got sick that daily life stopped. Stores closed, and healthcare workers and gravediggers were too ill to work. In many areas, large graves were dug, and bodies were buried without coffins.

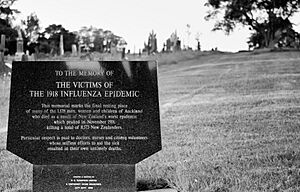

Some communities, especially on Pacific islands, were devastated. In Western Samoa, 22% of the population died in just two months. Many community elders died, which affected the sharing of traditional knowledge. In Alaska, some Indigenous villages almost disappeared.

Places That Avoided the Worst

Some places managed to avoid many deaths. American Samoa and the French colony of New Caledonia successfully used strict quarantines. They prevented the flu from causing widespread deaths for a long time. The isolated island of Marajó in Brazil also reported no outbreaks.

China's death toll is debated, but some studies suggest it might have been lower than in other parts of the world. This could be because the population had some immunity or because the flu didn't spread as widely in the country's interior.

The Flu's Lasting Impact

Impact on World War I

Some historians believe the flu affected the outcome of World War I. Data suggests that the flu hit the Central Powers (like Germany and Austria) harder than the Allied powers (like Britain and France). This might have weakened their armies more.

Economic Effects

Many businesses, especially in entertainment and services, lost money. However, the healthcare industry saw increased profits. The pandemic also helped women in nursing gain more recognition. This was partly because male doctors struggled to control the illness.

Long-Term Health and Education Effects

Studies have shown that people who were developing in their mothers' wombs during the pandemic had lasting effects. They often had less education, more physical disabilities, and lower incomes later in life. The flu has also been linked to a brain disease called encephalitis lethargica that appeared in the 1920s.

Survivors of the flu sometimes faced higher health risks later on. Some never fully recovered from the physical problems caused by the infection.

Remembering the Spanish Flu

For many years, the Spanish flu was largely forgotten by the public. It was overshadowed by World War I, which happened at the same time. Many young adults died in both the war and the flu, making it hard to separate the tragedies. The flu also moved so quickly that there wasn't much time for media coverage.

In Books and Movies

Despite its huge impact, the Spanish flu isn't a common theme in American literature. One well-known book is Katherine Anne Porter's 1939 novella Pale Horse, Pale Rider. More recently, the 2020 novel The Pull of the Stars is set in Dublin during the Spanish flu. Its publication was sped up because of the COVID-19 pandemic happening at the time.

Comparing Pandemics

| Name | Date | World pop. | Subtype | Reproduction number | Infected (est.) | Deaths worldwide | Case fatality rate | Pandemic severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish flu | 1918–20 | 1.80 billion | H1N1 | 1.80 (IQR, 1.47–2.27) | 33% (500 million) or >56% (>1 billion) | 17 –100 million | 2–3%, or ~4%, or ~10% | 5 |

| Asian flu | 1957–58 | 2.90 billion | H2N2 | 1.65 (IQR, 1.53–1.70) | >17% (>500 million) | 1–4 million | <0.2% | 2 |

| Hong Kong flu | 1968–69 | 3.53 billion | H3N2 | 1.80 (IQR, 1.56–1.85) | >14% (>500 million) | 1–4 million | <0.2% | 2 |

| 1977 Russian flu | 1977–79 | 4.21 billion | H1N1 | ? | ? | 0.7 million | ? | ? |

| 2009 swine flu pandemic | 2009–10 | 6.85 billion | H1N1/09 | 1.46 (IQR, 1.30–1.70) | 11–21% (0.7–1.4 billion) | 151,700–575,400 | 0.01% | 1 |

| Typical seasonal flu | Every year | 7.75 billion | A/H3N2, A/H1N1, B, ... | 1.28 (IQR, 1.19–1.37) | 5–15% (340 million – 1 billion) 3–11% or 5–20% (240 million – 1.6 billion) |

290,000–650,000/year | <0.1% | 1 |

| Notes | ||||||||

Scientific Research on the Flu

Scientists have worked hard to understand the 1918 flu virus. They believe the virus likely jumped directly from birds to humans. Pigs then caught the disease from humans.

Researchers have even managed to recreate the 1918 flu virus in labs. They used old tissue samples from flu victims buried in the Alaskan permafrost and from American soldiers. This allowed them to study how the virus worked.

In 2007, studies showed that monkeys infected with the recreated virus developed symptoms similar to the 1918 pandemic. They died from an overreaction of their immune systems. This helped explain why young, healthy people were so vulnerable. Their strong immune systems might have caused more damage to their bodies.

Research in 2008 found specific genes in the 1918 virus that allowed it to invade the lungs and cause severe pneumonia. In 2010, scientists discovered that the vaccine for the 2009 flu pandemic offered some protection against the 1918 strain.

Scientists continue to study the 1918 flu to learn how to prevent and control future pandemics.

See also

In Spanish: Pandemia de gripe de 1918 para niños

In Spanish: Pandemia de gripe de 1918 para niños

- 1918 flu pandemic in India

- 2009 swine flu pandemic

- Anti-Mask League of San Francisco

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Pandemic

- List of epidemics and pandemics

- List of Spanish flu cases

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |