Dengue fever facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dengue fever |

|

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Dengue, breakbone fever |

|

|

| The typical rash seen in dengue fever | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, rash |

| Complications | Bleeding, low levels of blood platelets, dangerously low blood pressure |

| Usual onset | 3–14 days after exposure |

| Duration | 2–7 days |

| Causes | Dengue virus by Aedes mosquitos |

| Diagnostic method | Detecting antibodies to the virus or its RNA |

| Similar conditions | Malaria, yellow fever, viral hepatitis, leptospirosis |

| Prevention | Dengue fever vaccine, decreasing mosquito exposure |

| Treatment | Supportive care, intravenous fluids, blood transfusions |

| Frequency | 390 million per year |

| Deaths | ~40,000 (2017) |

Dengue fever is a sickness spread by mosquitoes in warm, tropical places. It's caused by the dengue virus. Usually, symptoms start about 3 to 14 days after a person gets infected. These can include a high fever, headache, vomiting, and pains in the muscles and joints. A special skin rash and itching can also appear. Most people feel better in about 2 to 7 days.

In a few cases, dengue can become more serious. This is called dengue hemorrhagic fever. It can cause bleeding and very low levels of blood parts called platelets. Another serious form is dengue shock syndrome, where blood pressure drops to a very dangerous level.

Dengue is spread by certain types of female Aedes mosquitoes, especially Aedes aegypti. There are five different types of the dengue virus. If you get infected with one type, you usually become immune to it for life. However, you can still get infected with the other types. Getting infected a second time with a different type can make the sickness more severe. Doctors can test for the virus or its antibodies to find out if someone has dengue.

There are two dengue vaccines available to help prevent the disease. One is called Qdenga, approved for kids from four years old, teens, and adults. The other, Dengvaxia, is mostly for people who have already had dengue. To prevent dengue, it's important to get rid of places where mosquitoes lay eggs, like standing water. Also, wearing clothes that cover your body helps avoid mosquito bites. If someone has dengue, treatment focuses on helping them feel better. This includes giving fluids, sometimes through an IV. For very serious cases, a blood transfusion might be needed. Doctors recommend Paracetamol for fever and pain, not other pain relievers like ibuprofen, because they can increase the risk of bleeding.

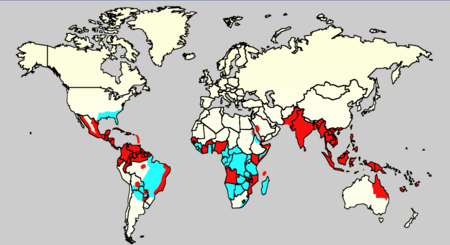

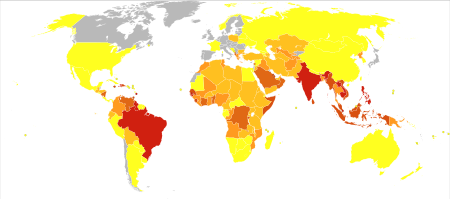

People first wrote about dengue outbreaks in 1779. Scientists understood how the virus spread by the early 1900s. After World War II, dengue became a big problem worldwide. It's now common in over 120 countries, especially in Southeast Asia, South Asia, and South America. About 390 million people get infected each year. Around half a million need to go to the hospital, and about 40,000 people die from it.

Contents

Signs and Symptoms of Dengue

Most people who get the dengue virus (about 80%) don't show any symptoms or only have a mild fever. Others get sicker, and for a small number, it can be life-threatening. Symptoms usually appear 4 to 7 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito. If you've traveled to a place where dengue is common and symptoms start more than 14 days after you get home, it's probably not dengue. Young children often have symptoms like a common cold or gastroenteritis (throwing up and diarrhea). They are also at a higher risk for serious problems, even if their first symptoms are mild.

How Dengue Sickness Progresses

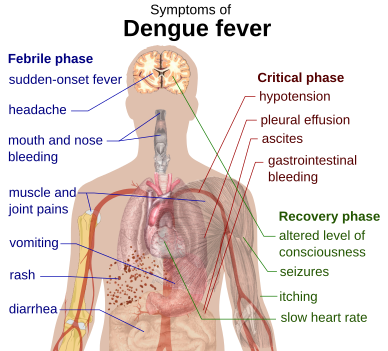

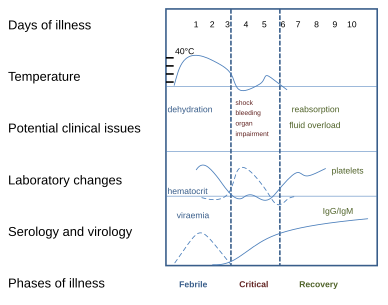

The main signs of dengue are a sudden high fever, a headache (often behind the eyes), and pain in muscles and joints. People sometimes call it "breakbone fever" because the muscle and joint pain can be very bad. The sickness has three stages: the febrile phase, the critical phase, and the recovery phase.

The febrile phase means you have a high fever, sometimes over 40°C (104°F). This stage usually lasts 2 to 7 days and comes with general body aches and a headache. You might also feel sick to your stomach and throw up. A rash appears in many people. It can look like flushed skin on the first or second day, or a measles-like rash later (days 4–7). Sometimes, the rash is described as "islands of white in a sea of red." Small red spots called petechiae might also show up. These are tiny broken blood vessels. You might also have some mild bleeding from your mouth or nose. The fever often goes away for a day or two and then comes back.

For some people, the sickness moves into a critical phase as the fever goes down. During this time, fluid can leak out of your blood vessels. This usually lasts one or two days. Fluid can build up in your chest or belly. This means less blood is circulating, which can lead to low blood pressure and not enough blood reaching important organs. Serious bleeding, often from the digestive system, can also happen. Shock (dengue shock syndrome) and severe bleeding (dengue hemorrhagic fever) happen in less than 5% of all dengue cases. However, people who have had dengue before with a different virus type are at a higher risk. This critical phase is rare but happens more often in children and young adults.

The recovery phase is when the leaked fluid goes back into the bloodstream. This usually takes 2 to 3 days. People often feel much better very quickly. They might have severe itching and a slow heart rate. Another rash can appear, and then the skin might peel. During this stage, too much fluid can build up in the body. If it affects the brain, it can cause confusion or seizures. Adults might feel tired for several weeks.

Other Health Problems with Dengue

Sometimes, dengue can affect other parts of the body, either alone or with the usual symptoms. About 0.5–6% of severe cases can cause confusion or a lower level of awareness. This can be due to inflammation of the brain from the virus or problems with organs like the liver.

Other brain and nerve problems have been reported with dengue. These include transverse myelitis and Guillain–Barré syndrome. Less common problems include heart infection and acute liver failure.

If a pregnant woman gets dengue, she has a higher risk of problems during pregnancy, like babies being born too small or too early.

What Causes Dengue?

The Dengue Virus

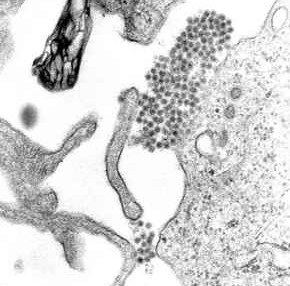

The dengue virus (DENV) is an RNA virus from the Flaviviridae family. Other viruses in this family include yellow fever virus and Zika virus. Most of these viruses are spread by arthropods like mosquitoes or ticks. That's why they are also called arboviruses, which means "arthropod-borne viruses."

The dengue virus has five different types, called serotypes: DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, DENV-4, and a fifth type found in 2013. These types are different based on how our immune system reacts to them.

How Dengue Spreads

Dengue virus is mainly spread by Aedes mosquitoes, especially Aedes aegypti. These mosquitoes usually live in warm areas, between 35° North and 35° South, and below 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) in height. They mostly bite in the early morning and evening, but they can bite at any time of day. Other Aedes species, like Aedes albopictus, can also spread the disease.

Humans are the main hosts for the virus, but it can also be found in monkeys. You can get infected from just one mosquito bite. A female mosquito bites a person who has dengue. The virus then infects the mosquito. About 8–10 days later, the virus moves to the mosquito's salivary glands. When the mosquito bites another person, it releases the virus into their saliva. The virus doesn't seem to harm the mosquito, and it stays infected for its whole life. Aedes aegypti is especially good at spreading dengue because it likes to lay eggs in man-made water containers, lives close to people, and prefers to feed on humans.

Dengue can also spread through infected blood products or organ donation. It has also been reported to spread from a mother to her baby during pregnancy or birth.

Who is More Likely to Get Severe Dengue?

Severe dengue is more common in babies and young children. Unlike many other infections, it's also more common in children who are well-fed. Other things that increase the risk of severe dengue include being female and having a higher body mass index.

Getting infected with one type of dengue virus usually gives you lifelong protection against that specific type. However, it only gives short-term protection against the other types. The risk of severe disease goes up if someone gets infected a second time with a different type of dengue virus. For example, if you had DENV-1 before and then get DENV-2 or DENV-3, your risk is higher. Dengue can also be dangerous for people with long-term health problems like diabetes or asthma.

How Dengue Works in the Body

When a mosquito carrying the dengue virus bites you, the virus enters your skin with the mosquito's saliva. It then enters white blood cells and makes copies of itself inside them. As these infected white blood cells move around your body, they release special proteins called cytokines and interferons. These proteins cause many of the symptoms you feel, like fever, flu-like symptoms, and severe pains.

In serious infections, the virus makes many more copies, and more organs like the liver and bone marrow can be affected. Fluid from your blood can leak out of small blood vessels into body spaces. This means less blood is circulating in your vessels, and your blood pressure can drop very low. This low blood pressure means vital organs might not get enough blood. Also, the virus can harm the bone marrow, which makes platelets. Platelets are needed for blood to clot. When you have fewer platelets, you have a higher risk of bleeding, which is another serious problem with dengue.

How the Virus Multiplies

Once in the skin, the dengue virus attaches to special cells called Langerhans cells. The virus gets inside these cells. Inside the cell, the virus uses the cell's machinery to make new viral proteins and copies of its genetic material. New, immature virus particles are formed and then mature. These new viruses are then released from the cell. They can then infect other white blood cells, like monocytes.

Infected cells first produce interferon, a protein that helps the body fight off viruses. However, some dengue virus types seem to have ways to slow down this defense. Interferon also helps activate the body's adaptive immune system. This system creates antibodies against the virus and T cells that directly attack infected cells. Some antibodies help destroy the virus, but others might accidentally help the virus get into cells where it can make more copies.

Why Severe Dengue Happens

It's not fully understood why a second infection with a different dengue virus type can lead to severe dengue. The most common idea is called antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). This means that antibodies from a past infection might actually help the new virus get into cells more easily, making the infection worse. Scientists are still studying this and other reasons why severe dengue occurs.

Severe dengue involves fluid leaking from blood vessels and problems with blood clotting. These changes are linked to how the lining of blood vessels works. Leaky blood vessels are thought to be caused by the immune system's reaction. Other factors include infected cells dying, which affects clotting, and low platelet counts, which also contribute to bleeding risks.

How Doctors Diagnose Dengue

|

Warning Signs of Severe Dengue

|

||||

| Worsening belly pain | ||||

| Throwing up a lot | ||||

| Liver getting bigger | ||||

| Bleeding from gums or nose | ||||

| High blood thickness with low platelets | ||||

| Feeling very sleepy or restless | ||||

| Fluid buildup in body cavities | ||||

Doctors often diagnose dengue based on a person's symptoms and a physical check-up, especially in areas where dengue is common. However, early dengue can look like other viral infections. A likely diagnosis is made if someone has a fever plus two of these: nausea and vomiting, rash, body pains, low white blood cell count, a positive tourniquet test, or any warning sign (see table). Warning signs usually appear before severe dengue starts.

The tourniquet test is helpful when lab tests aren't available. A blood pressure cuff is inflated on the arm for five minutes. Then, doctors count any tiny red spots (petechiae) that appear. More spots mean dengue is more likely.

Doctors should consider dengue if someone gets a fever within two weeks of visiting a tropical or subtropical place. It can be hard to tell dengue apart from chikungunya, another similar virus. Doctors often do tests to rule out other conditions like malaria, leptospirosis, typhoid fever, or influenza. Zika fever also has similar symptoms.

Early lab tests might show a low white blood cell count, followed by low platelets. Liver enzyme levels might be slightly high. In severe dengue, fluid leakage can make the blood thicker. Doctors might use ultrasound to find fluid buildup early, which can help identify dengue shock syndrome. Dengue shock syndrome is present if blood pressure drops very low. In children, this can be seen by slow capillary refill, a fast heart rate, or cold hands and feet.

How Dengue is Classified

The World Health Organization (WHO) now divides dengue into two groups: uncomplicated and severe. Severe dengue means there's serious bleeding, organ problems, or major fluid leakage. All other cases are uncomplicated. The older WHO classification, which is still sometimes used, had more categories, but the new one is simpler.

Lab Tests for Dengue

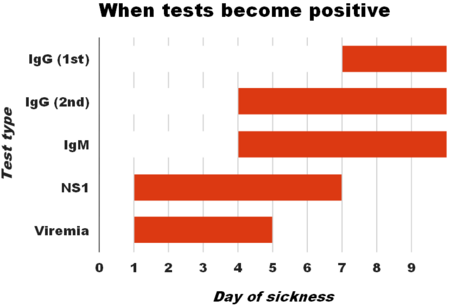

Lab tests can confirm dengue. This can be done by finding the virus itself, its genetic material (using PCR), or parts of the virus (like NS1 antigen). They can also look for specific antibodies in the blood. Finding the virus or its genetic material is more accurate but also more expensive and not always available. NS1 detection is good in the first week of a first infection. All tests can be negative in the very early stages. PCR and viral antigen tests are best in the first seven days.

Tests for dengue antibodies, called IgG and IgM, are useful later in the infection. Both IgG and IgM appear after 5–7 days. IgM levels are highest after a first infection and usually disappear after 30–90 days. IgG, however, can stay in the blood for over 60 years and shows if someone had dengue in the past. After a first infection, IgG levels peak in 2–3 weeks. In later infections, IgG levels rise faster and higher. Both IgG and IgM give protection against the specific type of virus that caused the infection. Sometimes, these antibody tests can give false positive results if you've recently had other similar viruses or vaccines. Finding IgM in someone with symptoms usually means they have dengue.

Preventing Dengue

Preventing dengue means controlling the mosquitoes that spread it and protecting yourself from bites. The World Health Organization suggests a plan with five parts:

- Getting public health groups and communities to work together.

- Working with different groups, both public and private.

- Using a combined approach to control the disease.

- Making decisions based on what works best.

- Building up local ability to respond to the situation.

The main way to control A. aegypti mosquitoes is to get rid of their breeding places. This means removing open sources of standing water. If water can't be removed, insecticides or biological agents (like fish that eat mosquito larvae) can be added. Widespread spraying of insecticides is sometimes done but isn't always effective. Reducing standing water is the best method.

People can avoid mosquito bites by wearing clothes that cover most of their skin. Using mosquito nets while resting and applying insect repellent (like DEET) also helps. While these steps protect individuals, they don't always stop outbreaks, which seem to be increasing. This might be because cities are growing, creating more places for A. aegypti to live. The areas where dengue is found are also expanding, possibly due to climate change.

Dengue Vaccines

Two dengue vaccines are available: Qdenga and Dengvaxia. Qdenga was approved in December 2022 for adults, teens, and children aged four and up. It is made by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company.

Dengvaxia became available in 2016. It's approved in many countries. However, Dengvaxia is only recommended for people who have already had dengue or in places where most people have been infected by age 9. If someone who has never had dengue gets this vaccine, it might make future infections worse. Because of this, some groups don't recommend it for widespread use.

Dengvaxia is made by Sanofi. It uses a weakened form of the yellow fever virus combined with parts of the four dengue types. Studies showed it was about 66% effective and prevented most severe cases.

Scientists are still working on new vaccines. An ideal vaccine would be safe, work after one or two shots, protect against all dengue types, not make severe disease worse, be easy to store, and be affordable.

Anti-Dengue Day

International Anti-Dengue Day is held every year on June 15th. The idea started in 2010, and the first event was in Jakarta, Indonesia, in 2011. The goals are to teach people about dengue, get help for prevention and control, and show that countries are working together to fight the disease.

Treating Dengue

There are no specific medicines that kill the dengue virus. However, keeping the right fluid balance in the body is very important. Treatment depends on a person's symptoms. If someone can drink, is peeing normally, has no "warning signs," and is otherwise healthy, they can be cared for at home. They should drink plenty of fluids and have daily check-ups. People with other health problems, warning signs, or who can't get regular check-ups should go to the hospital. Those with severe dengue need care in a hospital area with access to an intensive care unit.

If fluids are needed through an IV, it's usually only for one or two days. For children in shock from dengue, doctors give fluids quickly. The amount of fluid is then adjusted to keep urine output normal, vital signs stable, and blood thickness normal. The goal is to give the smallest amount of fluid needed.

Doctors avoid medical procedures that involve needles or tubes, like putting a tube into the nose or giving shots into muscles, because of the risk of bleeding. Paracetamol is used for fever and pain. NSAIDs like ibuprofen and aspirin are avoided because they can increase the risk of bleeding. Blood transfusions are given early if someone's vital signs are unstable and their blood is getting thinner, rather than waiting for blood levels to drop very low. Packed red blood cells or whole blood are usually recommended, not platelets or fresh frozen plasma. There isn't enough proof that corticosteroids help or harm people with dengue.

During the recovery phase, IV fluids are stopped to prevent too much fluid in the body. If there's too much fluid and vital signs are stable, just stopping fluids might be enough. If a person is past the critical phase, a medicine like furosemide might be used to help remove extra fluid.

What Happens After Dengue?

Most people with dengue get better without any lasting problems. For those with severe dengue, the risk of dying is low, about 0.8% to 2.5%. With good treatment, this risk is less than 1%. However, if blood pressure drops very low, the death rate can be higher, up to 26%. Children under five years old have a four times higher risk of a bad outcome than those over 10. Older people are also at higher risk.

Where Dengue is Found

As of 2019, dengue was common in over 120 countries. In 2013, about 60 million people worldwide had symptoms. About 18% of them needed hospital care, and around 13,600 people died. The cost of dengue worldwide is estimated at $9 billion. In the 2000s, 12 countries in Southeast Asia had about 3 million infections and 6,000 deaths each year. In 2019, the Philippines declared a national dengue emergency because of many deaths. Dengue is reported in at least 22 countries in Africa, and probably in all of them. This makes it one of the most common diseases spread by insects worldwide.

Infections are most often caught in cities. In recent decades, as towns and cities have grown, and people travel more, the number of outbreaks and circulating viruses has increased. Dengue, which used to be mostly in Southeast Asia, has now spread to other parts of Asia, the Pacific Ocean, and the Americas. It might even become a threat in Europe.

The number of dengue cases increased 30 times between 1960 and 2010. This rise is thought to be due to more people living in cities, population growth, more international travel, and global warming. Most dengue cases are found around the equator. Of the 2.5 billion people living in areas where dengue is common, 70% are in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific. Dengue is the second most common cause of fever (after malaria) for travelers returning from developing countries. The World Health Organization lists dengue as one of seventeen neglected tropical diseases.

The dengue virus stays in nature through cycles involving mosquitoes and animals. In forests, it's kept alive by female Aedes mosquitoes (not A. aegypti) passing it to their babies and to monkeys. In towns and cities, the virus is mainly spread by A. aegypti, which lives very close to humans. In rural areas, other Aedes species also spread it. Both A. aegypti and A. albopictus have spread to more places in the last half of the 20th century. Infected monkeys or humans greatly increase the number of dengue viruses circulating. Some experts think that climate change and city growth could put over 6 billion people at risk of dengue by 2080.

History of Dengue

The first possible record of dengue fever is in an old Chinese medical book from the Jin Dynasty (266–420 AD). It talked about a "water poison" linked to flying insects. The main mosquito that spreads dengue, A. aegypti, spread out of Africa between the 15th and 19th centuries, partly due to the slave trade and more global travel. There were descriptions of outbreaks in the 17th century. The clearest early reports of dengue outbreaks are from 1779 and 1780, when an epidemic spread across Southeast Asia, Africa, and North America. From then until 1940, outbreaks were not very common.

In 1906, scientists confirmed that Aedes mosquitoes spread dengue. In 1907, dengue was the second disease (after yellow fever) proven to be caused by a virus. More research helped scientists understand how dengue spreads.

The big spread of dengue during and after World War II is thought to be because of changes in the environment. These changes also led to different types of the disease spreading to new areas and the rise of dengue hemorrhagic fever. This severe form was first reported in the Philippines in 1953. By the 1970s, it was a major cause of death in children and had appeared in the Pacific and the Americas. Dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome were first seen in Central and South America in 1981.

What Does "Dengue" Mean?

The name "dengue" came into English in the early 1800s from Spanish. The Spanish word came from the Kiswahili term dinga, which means "disease caused by an evil spirit." The Spanish word dengue also means "fastidiousness," and people thought it fit because patients with dengue often didn't want to move. Slaves in the West Indies who got dengue were said to walk like a "dandy," so the disease was also called "dandy fever."

The term break-bone fever was used by American doctor Benjamin Rush in 1789. The term dengue fever became common after 1828.

Dengue in Society and Culture

Blood Donation and Dengue

When there are dengue outbreaks, more blood products are needed. However, fewer people can donate blood because they might be infected with the virus. Someone who has had dengue usually can't donate blood for at least six months.

Efforts to Raise Awareness

In India, National Dengue Day is held on May 16th to raise awareness. Efforts are ongoing to make it a global event. The Philippines has a dengue awareness month in June since 1998.

Research on Dengue

Scientists are working hard to prevent and treat dengue. This includes finding new ways to control mosquitoes, developing more vaccines, and creating antiviral medicines.

A vaccine candidate called TAK-003 showed good results in a study with over 20,000 children in areas where dengue is common. It was 73% effective and 90% effective for patients who needed to be hospitalized.

Mosquito Control Research

For mosquito control, new methods are being tried. These include putting small fish (like guppies) or tiny crustaceans called copepods into standing water to eat mosquito larvae. There are also trials with genetically modified male A. aegypti mosquitoes. When these modified males mate with females in the wild, their offspring cannot fly, which helps reduce mosquito numbers.

Wolbachia Bacteria

In 2021, research in Indonesia involved infecting A. aegypti mosquitoes with a special type of bacteria called Wolbachia. Mosquitoes infected with this bacteria were less likely to get the dengue virus. This method significantly reduced dengue cases in the areas where it was used.

New Treatments for Dengue

Besides controlling mosquitoes, scientists are trying to develop antiviral drugs to treat dengue fever attacks and prevent serious problems. Understanding the structure of the viral proteins can help in finding effective drugs. One approach is to stop the virus from copying its genetic material. Another is to block viral proteins that help the virus grow. Scientists are also looking for ways to stop the virus from entering cells.

Extracts from Carica papaya leaves have been studied and used in some hospitals for treatment. As of 2020, studies show it can help with blood levels, but more research is needed to see if it truly helps with the overall sickness. It's not yet a standard treatment.

In October 2021, a university in Belgium announced they developed an antiviral medicine that might also prevent the disease, working with Janssen Pharmaceutica.

See also

In Spanish: Dengue para niños

In Spanish: Dengue para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |