Benjamin Rush facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Benjamin Rush

|

|

|---|---|

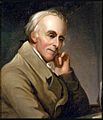

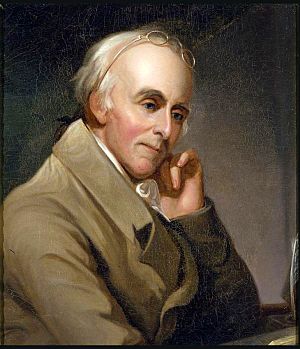

Portrait by Charles Willson Peale, c. 1818

|

|

| Born | January 4, 1746 |

| Died | April 19, 1813 (aged 67) |

| Resting place | Christ Church Burial Ground, Philadelphia |

| Alma mater | Princeton University University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Physician, writer, educator, medical doctor |

| Known for | Signer of the United States Declaration of Independence |

| Children | 13, including Richard |

| Signature | |

Benjamin Rush (January 4, 1746 – April 19, 1813) was an important leader in early American history. He was one of the Founding Fathers who signed the United States Declaration of Independence. Rush was a well-known doctor, politician, and social reformer in Philadelphia. He also helped start Dickinson College.

Rush was a delegate for Pennsylvania in the Continental Congress, which was like an early American government. He later served as the main doctor, or surgeon general, for the Continental Army during the American Revolution. After the war, he became a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, teaching about chemistry and medicine.

He was a big supporter of the American Enlightenment, a time when people focused on reason and new ideas. He strongly believed in the American Revolution and helped Pennsylvania approve the U.S. Constitution in 1788. Rush worked hard to improve many things, especially medicine and education. He was against slavery, wanted free public schools, and pushed for better education for women. He also wanted a fairer system for prisons.

As a leading doctor, Rush greatly influenced how medicine was practiced. He believed that illnesses came from imbalances in the body, often linked to the brain. This idea helped set the stage for future medical research. He also promoted public health by encouraging clean environments and good hygiene for everyone, including soldiers. His work on mental health problems made him one of the first American psychiatrists. In 1965, the American Psychiatric Association called him the "father of American psychiatry."

Contents

Early Life and Education

Benjamin Rush was born on January 4, 1746, in Byberry, Pennsylvania. His family was from England and lived on a farm near Philadelphia. He was the fourth of seven children. When he was only five years old, his father died. His mother then ran a country store to support the family.

At age eight, Benjamin went to live with his aunt and uncle to get a good education. He and his older brother Jacob attended a school run by Reverend Samuel Finley. This school later became West Nottingham Academy.

In 1760, when he was just fourteen, Rush graduated from the College of New Jersey. This college is now known as Princeton University. From 1761 to 1766, he trained to be a doctor under Dr. John Redman in Philadelphia. Dr. Redman encouraged him to study more at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. Rush studied there from 1766 to 1768 and earned his medical degree. While in Europe, he learned to speak French, Italian, and Spanish.

When he returned to the American colonies in 1769, Rush started his own medical practice in Philadelphia. He also became a chemistry professor at the College of Philadelphia. This college later became the University of Pennsylvania. Rush wrote the first American textbook on chemistry. He also wrote many important essays about patriotism.

Role in the Revolution

Rush was very active in the Sons of Liberty, a group that supported American independence. He was chosen to attend a meeting that sent delegates to the Continental Congress. This was a gathering of representatives from the colonies.

Thomas Paine asked Rush for advice when writing his famous pamphlet, Common Sense. This pamphlet strongly argued for independence from Britain. Starting in 1776, Rush represented Pennsylvania in the Continental Congress. He was one of the brave men who signed the United States Declaration of Independence. He also represented Philadelphia at Pennsylvania's own meeting to create its constitution.

While serving in the Continental Congress, Rush also used his medical skills to help the army. He went with the Philadelphia militia during battles when the British took over Philadelphia and much of New Jersey. He is even shown in a famous painting, The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777, helping wounded soldiers.

The Army Medical Service faced many problems. There were many injuries from battles and lots of sicknesses like typhoid and yellow fever. Despite these challenges, Rush became the surgeon-general for the middle part of the Continental Army. He wrote "Directions for preserving the health of soldiers," which became a key guide for keeping soldiers healthy. This guide was used for many years. However, Rush resigned in 1778. He reported that another doctor was misusing supplies meant for sick soldiers.

After the Revolution

In 1783, Benjamin Rush joined the staff of Pennsylvania Hospital. He worked there until he died. He was also chosen to be part of the Pennsylvania meeting that approved the U.S. Constitution. From 1797 to 1813, he served as the treasurer of the United States Mint. In 1788, he became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

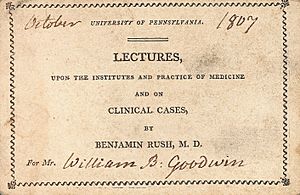

In 1791, he became a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He taught about medical theories and how to treat patients. At that time, doctors often used practices like bloodletting (removing blood from a patient) for almost any illness. This practice is now known to be harmful, but it was common back then. One of his students at the University of Pennsylvania was William Henry Harrison, who later became president. Rush was a strong supporter of ending slavery and was known as one of America's most famous doctors when he died.

Rush also helped found Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In 1794, he was recognized internationally and became a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. During the 1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic, Rush treated many patients. He used methods like bleeding and giving them calomel, which is a mercury-based medicine. These treatments were often not effective and sometimes made patients worse. His ideas were different from many French doctors who had more experience with yellow fever.

Rush was a founding member of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons. This group greatly influenced the building of Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia. He supported Thomas Jefferson for president in 1796.

Lewis and Clark Expedition

In 1803, President Jefferson sent Meriwether Lewis to Philadelphia to get ready for the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Benjamin Rush taught Lewis about illnesses they might face on the frontier. He also taught him about bloodletting.

Rush gave the expedition a medical kit. It included many "Dr. Rush's Bilious Pills." These were laxatives that contained a lot of mercury. The explorers often used these pills because their diet was mostly meat and they didn't always have clean water. Even though the pills' helpfulness is questioned today, the mercury in them has helped archaeologists track the expedition's path.

Important Reforms

Fighting Slavery

In 1766, when Benjamin Rush was traveling to study in Edinburgh, he saw 100 slave ships in Liverpool harbor. This sight deeply upset him. As a respected doctor and professor in Philadelphia, he spoke out strongly against the slave trade. He was a bold voice against slavery.

Against Capital Punishment

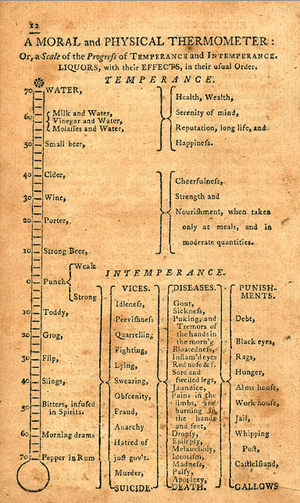

Rush believed that public punishments, like putting people in stocks, were not helpful. Instead, he suggested that criminals should be kept in private, work, and receive religious teaching. He was also against the death penalty. His strong opposition helped the Pennsylvania government stop using the death penalty for all crimes except first-degree murder.

Rush led Pennsylvania to create the first state prison, the Walnut Street Prison, in 1790. He argued that long-term imprisonment was a more humane but still serious punishment.

Improving Women's Status

After the American Revolution, Rush suggested a new way of educating young women from wealthy families. He thought they should learn English, music, dancing, sciences, bookkeeping, history, and moral philosophy. He was key in starting the Young Ladies' Academy of Philadelphia. This was the first school in Philadelphia chartered for women's higher education.

Rush believed that women should focus on moral essays, poetry, history, and religious writings. This type of education became very popular after the Revolution. Women took on a new role in shaping the young Republic. The idea of Republican motherhood emerged. This idea praised women for teaching their children about patriotism and the meaning of liberty. Rush did not support co-ed classrooms. He insisted that all young people should be taught about the Christian religion.

Medical Contributions

Physical Health Ideas

Benjamin Rush was a strong believer in "heroic medicine." This meant using very strong treatments. He firmly believed in practices like bloodletting and using purges with substances like calomel. These practices are now known to be generally harmful.

During the Philadelphia yellow fever outbreak in 1793, Rush was praised for staying in the city and treating many patients. Sometimes he treated up to 100 patients a day.

Rush also had some views on race that are now criticized. For example, he studied the case of Henry Moss, a slave whose dark skin color faded (likely due to vitiligo). Rush thought that being Black was a hereditary skin disease that could be cured. He wrote that this "disease" should make white people treat Black people with even more kindness.

Rush was also interested in the health of Native Americans. He wanted to understand why they seemed more likely to get certain illnesses. He wondered if they dreamed more or if their hair turned gray as they got older. He was fascinated by these questions as he believed studying "primitive men" could help social scientists understand their own civilization's history better.

Mental Health Care

Rush wrote one of the first books in American medicine about mental health problems. It was called Medical Inquiries and Observations, Upon the Diseases of the Mind (1812). In this book, he tried to classify different types of mental illness. He also thought about what caused them and how they could be cured.

After seeing mental patients living in terrible conditions at Pennsylvania Hospital, Rush led a successful effort in 1792. He pushed for the state to build a separate mental ward. Here, patients could be cared for in a more humane way.

Rush argued for more humane mental hospitals. He helped spread the idea that people with mental illness are sick, not like "inhuman animals." The official seal of the American Psychiatric Association even features an image of Rush's profile.

Educational Legacy

During his career, Benjamin Rush taught over 3,000 medical students. Many of his students went on to become important doctors. Some of them even founded Rush Medical College in Chicago in his honor after he died.

One of his students was Valentine Seaman. Seaman mapped where yellow fever deaths happened in New York. He also brought the smallpox vaccine to the United States in 1799. Another student was Samuel A. Cartwright, who later became a surgeon for the Confederate States of America. Rush University Medical Center in Chicago is also named after him.

Religious Views

Benjamin Rush believed strongly in the importance of Christianity in public life and education. He regularly attended Christ Church in Philadelphia. He was close friends with William White, who was a bishop there.

Rush supported the temperance movement, which encouraged people to drink less alcohol. He also supported public schools and Sunday schools. He helped start the Bible Society at Philadelphia, which is now called the Pennsylvania Bible Society. He also promoted the American Sunday School Union. When many public schools stopped using the Bible as a textbook, Rush suggested that the U.S. government should require its use. He even proposed that the government provide an American Bible to every family.

Rush also helped Richard Allen establish the African Methodist Episcopal Church. This was an important church founded by and for African Americans.

Personal Life

On January 11, 1776, Benjamin Rush married Julia Stockton (1759–1848). Julia was the daughter of Richard Stockton, another signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Benjamin and Julia had 13 children together. Nine of their children lived past their first year. Their son Richard later became a member of the cabinets for several U.S. presidents. These included James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor.

In 1812, Rush played a role in helping Thomas Jefferson and John Adams become friends again. He encouraged the two former presidents to start writing letters to each other once more.

Death

Benjamin Rush died on April 19, 1813, from typhus fever. He was 68 years old. He was buried with his wife Julia in the Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia. This is not far from where Benjamin Franklin is buried.

A small plaque honors Benjamin Rush at the site. The inscription on his grave marker reads: "In memory of

Benjamin Rush MD

he died on the 19th of April

in the year of our Lord 1813

Aged 68 years

Well done good and faithful servant

enter thou into the joy of the Lord"

Legacy

Many places and institutions are named after Benjamin Rush to honor his contributions. Benjamin Rush Elementary School in Redmond, Washington, was named by its students for him. The Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush is a magnet high school in Philadelphia that opened in 2008.

Rush County, Indiana, and its main town, Rushville, are named after him. Rush University Medical Center in Chicago also carries his name. Benjamin Rush State Park in Philadelphia is another place named in his honor.

Archival Collections

The Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has a collection of Benjamin Rush's original writings.

See also

In Spanish: Benjamin Rush para niños

In Spanish: Benjamin Rush para niños

Images for kids

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |