William Henry Harrison facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

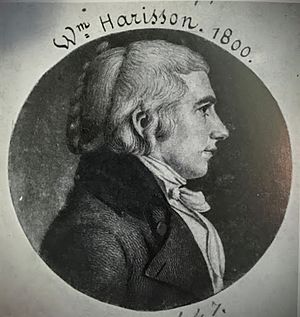

William Henry Harrison

|

|

|---|---|

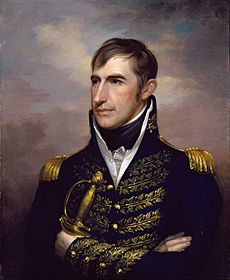

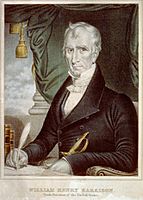

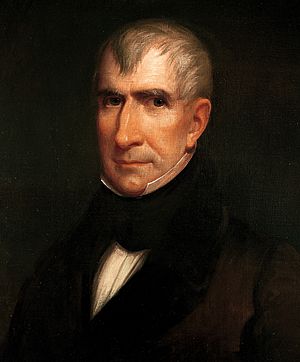

Official White House portrait by

James Lambdin, 1835 |

|

| 9th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1841 – April 4, 1841 |

|

| Vice President | John Tyler |

| Preceded by | Martin Van Buren |

| Succeeded by | John Tyler |

| 3rd United States Minister to Gran Colombia | |

| In office February 5, 1829 – September 26, 1829 |

|

| President | |

| Preceded by | Beaufort Taylor Watts |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Patrick Moore |

| United States Senator from Ohio |

|

| In office March 4, 1825 – May 20, 1828 |

|

| Preceded by | Ethan Allen Brown |

| Succeeded by | Jacob Burnet |

| Member of the Ohio Senate from the Hamilton County district |

|

| In office 1819–1821 |

|

| Preceded by | Ephraim Brown |

| Succeeded by | Ephraim Brown |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 1st district |

|

| In office October 8, 1816 – March 3, 1819 |

|

| Preceded by | John McLean |

| Succeeded by | Thomas R. Ross |

| 1st Governor of the Indiana Territory | |

| In office January 10, 1801 – December 28, 1812 |

|

| Appointed by | John Adams |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Posey |

| Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives from the Northwest Territory's at-large district |

|

| In office March 4, 1799 – May 14, 1800 |

|

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | William McMillan |

| 2nd Secretary of the Northwest Territory | |

| In office June 28, 1798 – October 1, 1799 |

|

| Governor | Arthur St. Clair |

| Preceded by | Winthrop Sargent |

| Succeeded by | Charles Willing Byrd |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 9, 1773 Charles City County, Virginia, British America |

| Died | April 4, 1841 (aged 68) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Harrison Tomb State Memorial |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 10, including John |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Harrison family of Virginia |

| Education |

|

| Awards | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Major General |

| Unit | Legion of the United States |

| Commands | Army of the Northwest |

| Battles/wars | |

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773 – April 4, 1841) was an American military leader and politician. He became the ninth President of the United States. Harrison holds the record for the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He died just 31 days after taking office in 1841.

He was the first U.S. president to die while in office. His death led to a brief constitutional crisis. This happened because the rules for what happens when a president dies were not fully clear in the U.S. Constitution at that time. Harrison was also the last president born as a British subject in the Thirteen Colonies. His grandson, Benjamin Harrison, later became the 23rd president.

Harrison was born into a famous family in Virginia. His father, Benjamin Harrison V, was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. Early in his military career, Harrison fought in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. This American victory ended the Northwest Indian War. Later, he led troops against Tecumseh's confederacy at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811. This battle earned him the nickname "Old Tippecanoe". During the War of 1812, he was promoted to major general. He led American forces to victory at the Battle of the Thames in Canada.

Harrison's political career started in 1798. He was appointed Secretary of the Northwest Territory. In 1799, he was elected as the territory's delegate to the United States House of Representatives. He became governor of the new Indiana Territory in 1801. As governor, he made many treaties with Native American tribes. These treaties added millions of acres of land to the nation.

After the War of 1812, Harrison moved to Ohio. In 1816, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1824, he was elected to the United States Senate. However, his Senate term was cut short. He was appointed as a diplomat to Gran Colombia in 1828.

Harrison returned to private life in North Bend, Ohio. In 1836, he was one of several Whig Party candidates for president. He lost to Democratic Vice President Martin Van Buren. Four years later, the Whig Party nominated him again. John Tyler was his running mate. Their campaign slogan was "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too". Harrison defeated Van Buren in the 1840 election. He was the first of only two Whigs to become president. The other was Zachary Taylor.

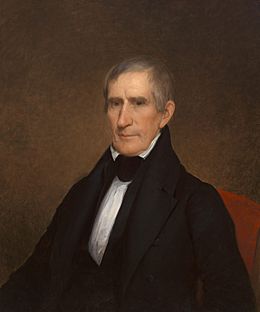

Just three weeks after his inauguration, Harrison became sick. He died a few days later. After some debate about the Constitution, Tyler became president. At 68, Harrison was the oldest person to become president until Ronald Reagan in 1981. Harrison is often not included in presidential rankings because his time in office was so short. However, he is remembered for his dealings with Native Americans and his creative election campaigns.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Harrison was the seventh and youngest child of Benjamin Harrison V and Elizabeth (Bassett) Harrison. He was born on February 9, 1773. His birthplace was Berkeley Plantation in Charles City County, Virginia. This was the home of his family, who were important politicians of English background. They had lived in Virginia since the 1630s. William Henry Harrison was the last American president not born as an American citizen.

His father was a Virginia planter. He was a delegate to the Continental Congress (1774–1777). He also signed the Declaration of Independence. Harrison's father was also the fifth governor of Virginia (1781–1784). This was during and after the American Revolutionary War. Harrison's older brother, Carter Bassett Harrison, was a representative for Virginia in the House of Representatives. William Henry often called himself a "child of the revolution." He grew up near where George Washington won the war against the British.

Harrison was taught at home until he was 14. Then he went to Hampden–Sydney College. This was a Presbyterian college in Virginia. He studied there for three years. He received a classical education, learning Latin, Greek, French, logic, and debate. His father took him out of the college, possibly for religious reasons. After short stays at other schools, he went to Philadelphia in 1790.

His father died in 1791. Harrison was then cared for by Robert Morris, a close family friend in Philadelphia. He briefly studied medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. His older brother inherited their father's money. So, Harrison did not have enough funds for more medical schooling. He also realized he did not like medicine. He left medical school. With help from his father's friend, Governor Henry Lee III, he started a military career.

Early Military Career

On August 16, 1791, Harrison, at age 18, joined the Army. He was made an ensign in the First American Regiment. He was first sent to Fort Washington in Cincinnati. This was in the Northwest Territory. The army was fighting in the Northwest Indian War there.

Harrison was promoted to lieutenant in 1792. This happened after Major General "Mad Anthony" Wayne took command of the western army. In 1793, Harrison became Wayne's aide-de-camp. He learned how to lead an army on the frontier. He fought in Wayne's important victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers on August 20, 1794. This battle ended the Northwest Indian War. Harrison was praised for his bravery in the battle.

Harrison signed the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. This treaty was between the U.S. and a group of Native American tribes. The tribes gave up some of their lands to the government. This opened up much of Ohio for settlement. In 1793, Harrison inherited some land and slaves from his mother. He later sold the land to his brother. Harrison became a captain in May 1797. He left the Army on June 1, 1798.

Marriage and Family Life

Harrison met Anna Tuthill Symmes in 1795. She was from North Bend, Ohio. Her father, Judge John Cleves Symmes, was a colonel in the Revolutionary War. Harrison asked the judge for permission to marry Anna, but he said no. So, they eloped and married on November 25, 1795. They honeymooned at Fort Washington. Judge Symmes later sold the Harrisons land in North Bend. This allowed Harrison to build a home and start a farm.

Anna was often sick during their marriage because of her many pregnancies. But she lived 23 years longer than William. She died on February 25, 1864, at age 88.

The Harrisons had ten children:

- Elizabeth Bassett (1796–1846)

- John Cleves Symmes (1798–1830)

- Lucy Singleton (1800–1826)

- William Henry Jr. (1802–1838)

- John Scott (1804–1878), who was the father of future U.S. president Benjamin Harrison

- Benjamin (1806–1840)

- Mary Symmes (1809–1842)

- Carter Bassett (1811–1839)

- Anna Tuthill (1813–1865)

- James Findlay (1814–1817)

Political Career

Harrison started his political career after leaving the military in 1798. He wanted a job in the Northwest Territorial government. His friend Timothy Pickering, who was Secretary of State, helped him. President John Adams appointed Harrison as the territory's secretary in July 1798. The work was boring, so he soon looked for a job in the U.S. Congress.

Serving in Congress

Harrison had many friends and became known as a frontier leader. He also had a successful horse-breeding business. Settlers in the Northwest Territory were worried about high land costs. Harrison became their advocate to lower these prices. The Northwest Territory had enough people by October 1799 to have a delegate in Congress. Harrison ran for election. He wanted to encourage more people to move to the territory. This would eventually lead to it becoming a state.

Harrison won the election by one vote. He became the Northwest Territory's first delegate to Congress in 1798, at age 26. He served from March 4, 1799, to May 14, 1800. He could not vote on laws. But he could serve on committees, suggest laws, and join debates. He led the Committee on Public Lands. He helped pass the Land Act of 1800. This law made it easier to buy land in the Northwest Territory. People could buy smaller plots at a lower cost. They only needed a five percent down payment. This helped the territory's population grow quickly.

Harrison also helped divide the Northwest Territory into two parts. The eastern part remained the Northwest Territory. It included Ohio and eastern Michigan. The western part was named the Indiana Territory. It included Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, part of western Michigan, and eastern Minnesota. These two new territories were officially created in 1800.

On May 13, 1800, President John Adams appointed Harrison as governor of the Indiana Territory. This was because of his connections to the west and his neutral political views. He served in this role for twelve years. He resigned from Congress to become the first Indiana territorial governor in 1801.

Indiana Territorial Governor

Harrison started his duties on January 10, 1801, in Vincennes. This was the capital of the Indiana Territory. Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison reappointed him as governor in 1803, 1806, and 1809. In 1804, Harrison also managed the government of the District of Louisiana for five weeks.

In 1805, Harrison built a large home near Vincennes. He called it Grouseland. It was one of the first brick buildings in the territory. It was a social and political center during his time as governor. Harrison also founded a university in Vincennes in 1801. It became Vincennes University in 1806. The capital later moved to Corydon in 1813.

Harrison's main job was to get land from Native American tribes. This would allow more people to settle and help the territory become a state. He also wanted to expand the territory for his own political future. He was seen as a good leader. Roads and other important things improved under his leadership.

When Harrison was reappointed governor in 1803, he gained more power to make treaties with Native Americans. The 1804 Treaty of St. Louis with Quashquame made the Sauk and Meskwaki tribes give up land in Illinois and Missouri. Many Sauk, especially their leader Black Hawk, were unhappy about losing their lands. The Treaty of Grouseland (1805) helped calm some tribes, but tensions remained high. The Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809) caused new problems. Harrison bought over 2.5 million acres from several tribes. Some Native Americans argued that the tribes who signed the treaty did not have the right to sell the land.

Harrison pushed hard for these treaties. He offered large payments to tribes and their leaders. In 1805, he gained about 51 million acres from Native Americans. This land was in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Missouri.

Harrison also supported slavery, which made him unpopular with those who wanted to end slavery in the Indiana Territory. In 1803, he tried to get Congress to temporarily stop a rule that banned slavery in the territory. He said it was needed to help the territory grow and become a state, but his idea failed. In 1807, with Harrison's support, the territory passed laws that allowed indentured servitude. This gave masters control over how long people had to work for them.

President Jefferson, who wrote the Northwest Ordinance, secretly worked to stop Harrison's pro-slavery efforts. In 1809, the Indiana Territory held its first elections for the legislature. Harrison found himself disagreeing with the legislature. This was because people who wanted to end slavery gained power. The eastern part of the Indiana Territory had many people who were against slavery. The legislature then ended the indenturing laws. After 1809, the Indiana legislature gained more power, and the territory moved closer to becoming a state.

Army General

Tecumseh and Tippecanoe

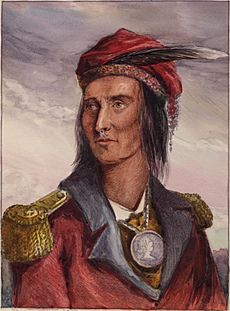

Native American resistance to American expansion grew. It was led by the Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa (also called "The Prophet"). This conflict became known as Tecumseh's War. Tenskwatawa told the tribes that the Great Spirit would protect them if they fought the settlers. He encouraged them to resist by not paying white traders fully and by giving up white customs.

Harrison learned about this resistance from spies. He asked President Madison for money to prepare for war. Madison was slow to respond. Harrison tried to negotiate. He sent a letter to Tecumseh, saying the U.S. Army was "more numerous than you can count."

In August 1810, Tecumseh led 400 warriors to meet Harrison in Vincennes. They wore war paint, which at first scared the soldiers. The leaders met Harrison at Grouseland. Tecumseh strongly argued that the Fort Wayne Treaty was not fair. He said one tribe could not sell land without other tribes agreeing. He asked Harrison to cancel the treaty. He warned Americans not to settle on the lands sold in the treaty. Tecumseh also said his group of tribes was growing fast.

Harrison said that individual tribes owned the land and could sell it as they wished. He disagreed that all Native Americans were one nation. He said each tribe could have its own relationship with the United States. Harrison argued that if they were one nation, the Great Spirit would have made them speak one language.

Tecumseh then became very angry and called Harrison a liar. A Shawnee who was friendly to Harrison got his pistol ready. This warned Harrison that Tecumseh's speech was causing trouble. Some people said Tecumseh was telling his warriors to kill Harrison. Many warriors started to pull their weapons. This was a big threat to Harrison and the town, which had only 1,000 people. Harrison drew his sword. Tecumseh's warriors backed down when the officers showed their firearms. Chief Winamac, who was friendly to Harrison, told the warriors to go home peacefully. Before leaving, Tecumseh told Harrison he would join the British if the Fort Wayne Treaty was not canceled. After the meeting, Tecumseh traveled to unite many tribes against the United States.

Harrison worried that Tecumseh's actions would stop Indiana from becoming a state. He also worried about his own political future. In 1811, Tecumseh was traveling, and Tenskwatawa was in charge. Harrison saw this as a chance. He told the Secretary of War, William Eustis, to show military strength to the Native American group. Harrison, who had not been in military action for 13 years, convinced Madison and Eustis to let him lead.

He led an army of 950 men north to make the Shawnee agree to peace. But the tribes launched a surprise attack on November 7 in the Battle of Tippecanoe. Harrison fought back and defeated the tribal forces near the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers. This battle became famous, and he was seen as a national hero. Although his troops had more casualties, the Shawnee prophet's idea of spiritual protection was broken. Tenskwatawa and his forces fled to Canada. Their plan to unite the tribes of the region failed.

When Harrison reported to Secretary Eustis, he said he had expected an attack. The first report was unclear about who won. The secretary thought it was a defeat until a clearer report came. When no second attack happened, the Shawnee defeat was certain. Eustis asked why Harrison had not prepared his camp better. Harrison said he thought the position was strong enough. This disagreement led to problems between Harrison and the Department of War.

The press did not cover the battle at first. Then, one Ohio paper wrongly said Harrison was defeated. But by December, most major American newspapers reported the victory. Public anger against the Shawnee grew. Americans blamed the British for encouraging the tribes and giving them weapons. Congress declared war on June 18, 1812. Harrison then left Vincennes to seek a military appointment.

War of 1812 Service

When the war with the British started in 1812, conflicts with Native Americans in the Northwest continued. Harrison briefly served as a major general in the Kentucky militia. On September 17, he was given command of the Army of the Northwest. He received military pay and also his governor's salary until December 28. Then he officially resigned as governor to focus on military service.

The Americans lost a battle in the siege of Detroit. General James Winchester offered Harrison a lower rank. But Harrison wanted full command of the army. President James Madison removed Winchester from command in September. Harrison then became the leader of the new soldiers. He was ordered to take back Detroit and improve morale. But he held back at first. The British and their Native American allies had many more troops than Harrison's army. So, Harrison built a defensive position during the winter. It was along the Maumee River in northwest Ohio. He named it Fort Meigs.

In 1813, Harrison received more soldiers. He then went on the attack. He led the army north to battle. He won victories in the Indiana Territory and Ohio. He recaptured Detroit. Then he invaded Upper Canada (Ontario). His army defeated the British. Tecumseh was killed on October 5, 1813, at the Battle of the Thames. This was seen as one of the greatest American victories in the war. It made Harrison famous across the nation.

In 1814, Secretary of War John Armstrong split the army's command. He gave Harrison a less important post and put one of Harrison's officers in charge of the main front. Armstrong and Harrison had disagreed about the invasion of Canada. Harrison resigned from the army in May. After the war, Congress looked into Harrison's resignation. They decided that Armstrong had treated him unfairly. Congress gave Harrison a gold medal for his service during the war.

Harrison and Michigan Territory's Governor Lewis Cass helped make a peace treaty with the Native Americans. In June 1815, President Madison appointed Harrison to help negotiate another treaty. This was the Treaty of Springwells. In this treaty, the tribes gave up a large area of land in the west. This provided more land for Americans to buy and settle.

Life After the War

Ohio Politician and Diplomat

Harrison left the army in 1814 and returned to his farm in North Bend, Ohio. He was in debt because his spending was more than his income. He was elected in 1816 to the House of Representatives. He represented Ohio's 1st congressional district until 1819. He tried to become Secretary of War in 1817 but did not get the job. He was also not chosen for a diplomatic job in Russia. He was elected to the Ohio State Senate in 1819 and served until 1821. He lost the election for Ohio governor in 1820. In 1824, he was elected to the U.S. Senate. He was also an Ohio presidential elector in 1820 for James Monroe and in 1824 for Henry Clay.

In 1828, Harrison was appointed as a diplomat to Gran Colombia. He resigned from Congress and served until March 8, 1829. He arrived in Bogotá in December 1828. He found Colombia in a sad state. He told the Secretary of State that the country was close to chaos. He also said that Simón Bolívar was about to become a military dictator. Harrison wrote a polite letter to Bolívar. He said that "the strongest of all governments is that which is most free." He asked Bolívar to support democracy. Bolívar replied that the United States "seem destined by Providence to plague America with torments in the name of freedom." This statement became famous in Latin America.

Harrison made some mistakes in Colombia. He did not stay neutral in Colombian affairs. He publicly opposed Bolívar. Colombia then asked for his removal. Andrew Jackson became president in March 1829. He recalled Harrison to make his own appointment.

Private Citizen Life

Harrison returned to the United States and his North Bend farm. He lived a private life after almost 40 years of government service. He had not become rich during his life. He lived on his savings, a small pension, and money from his farm.

In May 1817, Harrison helped found Christ Church in downtown Cincinnati. This was an Episcopal church. Harrison served on its board from 1817 to 1819, and again in 1824.

His local supporters helped him by appointing him Clerk of Courts for Hamilton County. He worked there from 1836 to 1840. He also grew corn on his farm.

Around this time, he met George DeBaptiste, an abolitionist and conductor on the Underground Railroad. DeBaptiste lived nearby in Madison. They became friends. Harrison once wrote, "we might look forward to a day when a North American sun would not look down upon a slave." DeBaptiste later became Harrison's valet and then a White House steward.

1836 Presidential Campaign

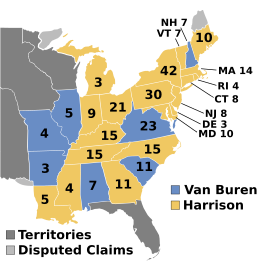

Harrison was the western Whig candidate for president in 1836. He was one of four regional Whig candidates. The others were Daniel Webster, Hugh L. White, and Willie P. Mangum. The Whigs had more than one candidate. They hoped to defeat the current Vice President, Martin Van Buren, who was a popular Democrat. The Democrats said the Whigs were trying to stop Van Buren from winning enough electoral votes. They claimed the Whigs wanted to force the election to be decided in the House of Representatives. This plan, if it existed, did not work. Harrison came in second place. He won nine of the 26 states.

Harrison ran in all the non-slave states except Massachusetts. He also ran in the slave states of Delaware, Maryland, and Kentucky. Van Buren won the election with 170 electoral votes. If Harrison had won just over 4,000 more votes in Pennsylvania, he would have gotten that state's 30 electoral votes. Then the election would have been decided in the House of Representatives.

1840 Presidential Campaign

In the 1840 election, Harrison faced the current president, Van Buren. Harrison was the only Whig candidate this time. The Whigs saw Harrison as a war hero from the South. They thought he would be a good contrast to Van Buren, who they saw as distant and aristocratic. Harrison was chosen over other more controversial party members like Clay and Webster. His campaign focused on his military record. It also highlighted the weak U.S. economy caused by the Panic of 1837.

The Whigs blamed Van Buren for the economic problems. They nicknamed him "Van Ruin." The Democrats, in turn, made fun of Harrison. They called him "Granny Harrison, the petticoat general." This was because he left the army before the War of 1812 ended. They also pointed out that Harrison's name spelled backward was "No Sirrah." They tried to make him seem like an old, out-of-touch man. They said he would rather "sit in his log cabin" than run the country. This strategy backfired. Harrison and his running mate John Tyler adopted the log cabin as a campaign symbol.

Harrison came from a rich, slave-owning family in Virginia. But his campaign presented him as a humble frontiersman. This was similar to how Andrew Jackson was portrayed. Van Buren was shown as a wealthy elitist. A famous example was the Gold Spoon Oration. This speech by Charles Ogle made fun of Van Buren's fancy White House lifestyle.

The Whigs boasted about Harrison's military record. They highlighted his reputation as the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe. The campaign slogan "Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too" became very famous. Van Buren campaigned from the White House. Harrison was out on the campaign trail. He entertained people with impressions of Native American war cries. He helped people forget the nation's economic problems. In June 1840, a Harrison rally at the Tippecanoe battle site drew 60,000 people. Voter turnout was very high, at 80%. This was 20 points higher than the previous election. Harrison won a huge victory in the Electoral College, 234 electoral votes to Van Buren's 60. The popular vote was much closer. But Harrison won 19 of the 26 states.

Presidency (1841)

Inauguration Day

When Harrison came to Washington, he wanted to show he was still the strong hero of Tippecanoe. He also wanted to show he was a well-educated and thoughtful man. He took the oath of office on Thursday, March 4, 1841. It was a cold and wet day. He bravely faced the chilly weather without an overcoat or hat. He rode on horseback to the ceremony. Then he gave the longest inaugural address in American history, with 8,445 words. It took him almost two hours to read.

His speech was a detailed plan for the Whig Party. It rejected the policies of Jackson and Van Buren. Harrison promised to bring back the Second Bank of the United States. He also planned to use his veto power only if a law was unconstitutional. He promised to use his power to appoint qualified people, not just friends. He also said he would not run for a second term. He criticized the financial problems of the previous government. He promised not to interfere with Congress's financial plans. Overall, Harrison promised a presidency where he would let Congress lead.

He also spoke about slavery, which was a big issue in the country. Harrison's speech gave some ideas about what his presidency would be like. He said he would only serve one term. He would not misuse his veto power. He left financial plans to Congress. He was against upsetting the Southern United States about slavery. He said little about the national bank, except that he was open to paper money. Harrison's idea of the presidency was very limited. This matched his Whig political beliefs.

After the speech, he rode in the inaugural parade. He stood in a three-hour line at the White House to greet people. That evening, he went to three inaugural balls. One was called the "Tippecanoe" ball. It had 1,000 guests who paid $10 each.

Dealing with Appointments

Clay was a leader of the Whigs. He was also a powerful lawmaker and had wanted to be president himself. He expected to have a lot of influence in Harrison's government. He tried to tell Harrison who to appoint to his Cabinet and other jobs. Harrison refused his demands. He told Clay, "Mr. Clay, you forget that I am the President." The disagreement grew when Harrison named Daniel Webster as Secretary of State. Webster was Clay's main rival for control of the Whig Party. Harrison also seemed to give Webster's supporters some important jobs. His only concession to Clay was appointing Clay's friend John J. Crittenden as Attorney General. Despite this, the arguments continued until Harrison's death.

| The Harrison Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | William Henry Harrison | 1841 |

| Vice President | John Tyler | 1841 |

| Secretary of State | Daniel Webster | 1841 |

| Secretary of Treasury | Thomas Ewing | 1841 |

| Secretary of War | John Bell | 1841 |

| Attorney General | John J. Crittenden | 1841 |

| Postmaster General | Francis Granger | 1841 |

| Secretary of the Navy | George Edmund Badger | 1841 |

Many people wanted jobs from Harrison's election. Crowds of job seekers came to the White House. It was open to anyone who wanted to meet the president. Most of Harrison's time during his month as president was spent on social events and meeting visitors. He was advised to have his government ready before his inauguration. But he wanted to focus on the celebrations. So, people looking for jobs waited for him at all hours. They filled the White House.

Harrison wrote in a letter on March 10, "I am so much harassed by the multitude that calls upon me that I can give no proper attention to any business of my own." One story says that the White House halls were so full one afternoon that Harrison had to be helped out a window. He walked around the outside of the White House and then was helped in through another window to get to a meeting.

Harrison took his promise to change appointments seriously. He visited each of the six cabinet departments to see how they worked. He issued an order that employees who campaigned for political parties would be fired. He resisted pressure from other Whigs about giving jobs based on party loyalty. On March 16, a group came to his office. They demanded that all Democrats be removed from appointed jobs. Harrison said, "So help me God, I will resign my office before I can be guilty of such an iniquity!"

His own cabinet tried to stop his appointment of John Chambers as Governor of the Iowa Territory. They wanted Webster's friend James Wilson instead. Webster tried to push this decision at a cabinet meeting on March 25. Harrison asked him to read a handwritten note. It simply said "William Henry Harrison, President of the United States." Harrison then stood and said: "William Henry Harrison, President of the United States, tells you, gentlemen, that, by God, John Chambers shall be governor of Iowa!"

Harrison's only other important decision was whether to call Congress into a special session. He and Clay had disagreed about this. Harrison's cabinet was split evenly. So, the president first said no. Clay pushed him again on March 13. Harrison refused and told him to only contact him in writing. However, a few days later, Treasury Secretary Thomas Ewing told Harrison that federal money was in such trouble. The government could not keep running until Congress's regular session in December. So, Harrison agreed. He announced the special session on March 17. It was for "the condition of the revenue and finance of the country." The session would have started on May 31 if Harrison had lived.

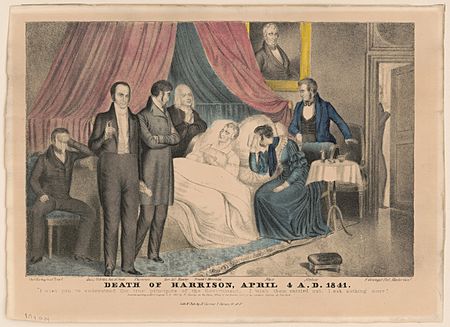

Death and Funeral

Harrison was worn out by many people seeking jobs and a busy social schedule. On Wednesday, March 24, 1841, Harrison took his usual morning walk to local markets. He did not wear a coat or hat. He was caught in a sudden rainstorm. He did not change his wet clothes when he returned to the White House. On Friday, March 26, Harrison became sick with cold-like symptoms. He sent for his doctor, Thomas Miller. The next day, Saturday, the doctor was called again. He found Harrison in bed with a "severe chill" after another early morning walk. As his symptoms got worse, a team of doctors was called on Monday, March 29. They confirmed he had pneumonia.

No official announcements were made about Harrison's illness. This led to public rumors and worry. Washington society noticed he was not at church on Sunday. Conflicting newspaper reports came from people with contacts in the White House. A Washington paper reported on Thursday, April 1, that Harrison's health was much better. But in fact, Harrison's condition had gotten much worse. Cabinet members and family were called to the White House. His wife Anna was still in Ohio because she was sick. According to Washington papers on Friday, Harrison had improved. But a Baltimore Sun report said his condition was "more dangerous." A reporter for the New York Commercial said that "the country's people were deeply distressed and many of them in tears."

On the evening of Saturday, April 3, Harrison became confused. At 8:30 p.m., he said his last words to his doctor. They were likely meant for Vice President John Tyler: "Sir, I wish you to understand the true principles of the government. I wish them carried out. I ask nothing more." Harrison died at 12:30 a.m. on April 4, 1841. This was Palm Sunday. He died nine days after getting sick and exactly one month after taking office. He was the first president to die in office. Anna was still in Ohio packing for her trip to Washington when she learned he had died.

The common belief at the time was that his illness was caused by the bad weather at his inauguration. Modern analysis suggests he likely died from an infection, possibly from the White House water supply.

A 30-day period of mourning began after the president's death. The White House held public ceremonies, similar to European royal funerals. A funeral service was held on April 7 in the East Room of the White House. After that, Harrison's coffin was taken to Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. It was placed in the Public Vault.

In June, Harrison's body was moved by train and river barge to North Bend, Ohio. He was buried on July 7 at the top of Mt. Nebo. This place is now the William Henry Harrison Tomb State Memorial.

Tyler Becomes President

On April 5, Fletcher Webster, the son of Secretary of State Daniel Webster, told Tyler that Harrison had died. Tyler was visiting family in Williamsburg. Tyler arrived in Washington on the morning of April 6. That same day, Tyler was sworn into office in front of Harrison's cabinet. On April 9, Tyler gave a short speech. In his speech, Tyler did not offer personal comfort to Harrison's wife Anna or family. Tyler did praise Harrison. He said Harrison had been elected for a "great work" of cleaning up corruption in the government. Tyler and his family moved into the White House one week after Harrison's funeral. The White House rooms were still decorated with black mourning cloths. Harrison's wife Anna was still in Ohio, planning to move to Washington in May, when she heard about his death. Anna never moved into the White House. Harrison's daughter-in-law, Jane Irwin Harrison, had served as the White House hostess in Anna's place while Harrison was president.

Impact of Harrison's Death

Harrison's death highlighted a unclear part of the Constitution. This was about who takes over the presidency. Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 said the vice president would take over the "Powers and Duties of the said Office" if a president died. But it was not clear if the vice president officially became president, or just temporarily took on the duties.

Harrison's cabinet insisted that Tyler was "Vice President acting as President." Tyler was firm that he was the President. He was determined to use all the powers of the presidency. The cabinet talked with Chief Justice Roger Taney. They decided that if Tyler took the presidential oath, he would become president. Tyler did so and was sworn into office on April 6, 1841. Congress met. On May 31, 1841, after a short debate, they passed a resolution. This confirmed Tyler as president for the rest of Harrison’s term. This rule set by Congress in 1841 was followed seven times when a president died. It was later added to the Constitution in 1967 through the Twenty-fifth Amendment.

Legacy and Honors

Historical Reputation

One of Harrison's lasting impacts is the series of treaties he made with Native American leaders. This happened when he was the Indiana territorial governor. These treaties led to tribes giving up large areas of land in the west. This provided more land for the nation to buy and settle.

Harrison's influence on American politics also includes his campaign methods. These methods helped create modern presidential campaign tactics. Harrison died with very little money. Congress voted to give his wife Anna a pension of $25,000. This was one year of Harrison's salary. She also could mail letters for free.

Harrison is seen as "the most dominant figure in the evolution of the Northwest territories into the Upper Midwest today." Harrison was 68 when he became president. He was the oldest person to become U.S. president until Ronald Reagan in 1981.

Harrison's son, John Scott Harrison, represented Ohio in the House of Representatives from 1853 to 1857. Harrison's grandson, Benjamin Harrison, became the 23rd president from 1889 to 1893. This makes William and Benjamin Harrison the only grandparent-grandchild pair of presidents.

Honors and Tributes

Many monuments and statues honor Harrison. There are public statues of him in downtown Indianapolis, Cincinnati's Piatt Park, the Tippecanoe County Courthouse, Harrison County, Indiana, and Owen County, Indiana. Many counties and towns are also named after him.

The Village of North Bend, Ohio, celebrates Harrison's birthday every year with a parade. The Gen. William Henry Harrison Headquarters in Franklinton, Ohio, remembers Harrison. This house was his military headquarters from 1813 to 1814. On February 19, 2009, the U.S. Mint released the ninth coin in the Presidential $1 Coin Program. It has Harrison's picture on it.

-

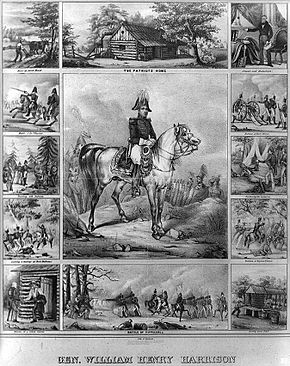

Chromolithograph print

-

Equestrian statue of Harrison in Cincinnati, by Louis Rebisso

See also

In Spanish: William Henry Harrison para niños

In Spanish: William Henry Harrison para niños

- Curse of Tippecanoe

- List of presidents of the United States

- List of presidents of the United States by previous experience

- List of presidents of the United States who died in office

- Presidents of the United States on U.S. postage stamps

- Second Party System

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |