Daniel Webster facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Daniel Webster

|

|

|---|---|

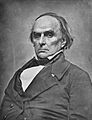

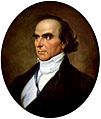

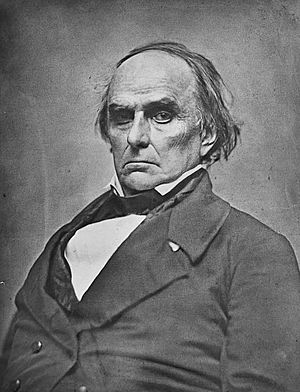

Daniel Webster, c. 1847

|

|

| 14th and 19th U.S. Secretary of State | |

| In office July 23, 1850 – October 24, 1852 |

|

| President | Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | John M. Clayton |

| Succeeded by | Charles Magill Conrad |

| In office March 6, 1841 – May 8, 1843 |

|

| President | William Henry Harrison John Tyler |

| Preceded by | John Forsyth |

| Succeeded by | Abel P. Upshur |

| Chair of the Senate Finance Committee | |

| In office December 2, 1833 – December 5, 1836 |

|

| Preceded by | John Forsyth |

| Succeeded by | Silas Wright |

| United States Senator from Massachusetts |

|

| In office June 8, 1827 – February 22, 1841 |

|

| Preceded by | Elijah H. Mills |

| Succeeded by | Rufus Choate |

| In office March 4, 1845 – July 22, 1850 |

|

| Preceded by | Rufus Choate |

| Succeeded by | Robert Charles Winthrop |

| Chair of the House Judiciary Committee | |

| In office 1823–1827 |

|

| Preceded by | Hugh Nelson |

| Succeeded by | Philip P. Barbour |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives |

|

| In office March 4, 1823 – May 30, 1827 |

|

| Preceded by | Benjamin Gorham |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Gorham |

| Constituency | Massachusetts's 1st district |

| In office March 4, 1813 – March 3, 1817 |

|

| Preceded by | George Sullivan |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Livermore |

| Constituency | New Hampshire's at-large district |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 18, 1782 Salisbury, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | October 24, 1852 (aged 70) Marshfield, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Federalist (before 1825) National Republican (1825–1833) Whig (1833–1852) |

| Spouses | Grace Fletcher Caroline LeRoy Webster |

| Children | 5, including Fletcher |

| Education | Phillips Exeter Academy Dartmouth College (BA) |

| Signature | |

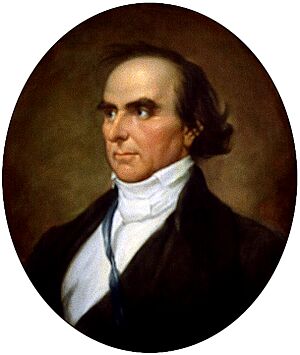

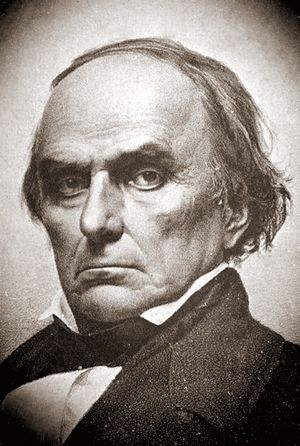

Daniel Webster (born January 18, 1782 – died October 24, 1852) was an important American lawyer and politician. He represented the states of New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress. He also served as the 14th and 19th U.S. Secretary of State for Presidents William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Millard Fillmore.

Webster was one of the most famous American lawyers in the 1800s. He argued over 200 cases in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. During his life, he was a member of the Federalist Party, the National Republican Party, and the Whig Party.

Born in New Hampshire, Webster became a successful lawyer after college. He was against the War of 1812 and was elected to the United States House of Representatives. He later moved to Boston and became a top lawyer for the Supreme Court. He won important cases like Dartmouth College v. Woodward and McCulloch v. Maryland.

Webster returned to the House in 1823 and supported President John Quincy Adams. He was elected to the United States Senate in 1827. There, he helped create the National Republican Party with Henry Clay.

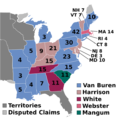

After Andrew Jackson became president, Webster strongly disagreed with his policies. Webster famously spoke against the idea of nullification, where states claimed they could ignore federal laws. His "Second Reply to Hayne" speech is considered one of the best speeches ever given in Congress. He joined the Whig Party and ran for president in 1836 but lost.

In 1841, President Harrison made Webster his Secretary of State. Webster stayed in this role even after Harrison died and John Tyler became president. As Secretary of State, Webster helped negotiate the Webster–Ashburton Treaty, which settled border disputes with Britain.

Webster returned to the Senate in 1845. He was a leader of the "Cotton Whigs," who wanted good relations with the Southern states. In 1850, President Fillmore appointed Webster as Secretary of State again. Webster helped pass the Compromise of 1850, which tried to solve issues about slavery and new territories. This compromise was not popular in the North and hurt Webster's standing. He tried to become president in 1852 but did not get his party's nomination.

Many people see Daniel Webster as a very important and talented lawyer, speaker, and politician.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Rising to Fame

- Congressman and Constitutional Lawyer

- First Time in the Senate

- Secretary of State in the Tyler Administration

- Second Time in the Senate

- Secretary of State in the Fillmore Administration

- Personal Life and Family

- Death

- Legacy and Remembrance

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education

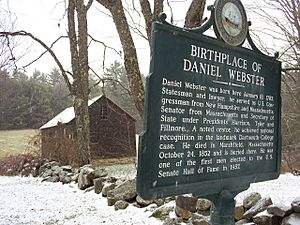

Daniel Webster was born on January 18, 1782, in Salisbury, New Hampshire. His birthplace is now part of Franklin. His father, Ebenezer Webster, was a farmer and local official who fought in the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War.

Daniel was the second-youngest of eight children. He was very close to his older brother, Ezekiel. As a child, Daniel often helped on the family farm, but he was frequently sick. His parents encouraged him to read, and he enjoyed books by authors like Alexander Pope.

In 1796, he went to Phillips Exeter Academy, a school in Exeter, New Hampshire. After that, he was accepted into Dartmouth College in 1797. At Dartmouth, he managed the school newspaper and became known as a strong public speaker. He gave a famous speech in 1800 that showed his political ideas.

Like his father, Webster believed in the Federalist Party and a strong central government. He graduated from Dartmouth in 1801.

Becoming a Lawyer

After college, Webster trained with a lawyer named Thomas W. Thompson. He wasn't very excited about studying law, but he thought it would help him live comfortably. To help his brother Ezekiel study at Dartmouth, Webster briefly worked as a schoolteacher in Fryeburg, Maine.

In 1804, he got a job in Boston with a famous lawyer, Christopher Gore. Working for Gore, Webster learned a lot about law and politics. He met many important New England politicians. He loved Boston and became a lawyer there in 1805.

Rising to Fame

After becoming a lawyer, Webster started his own practice in Boscawen, New Hampshire. He became more involved in politics, supporting Federalist causes. When his father died in 1806, he gave his practice to his brother and moved to the larger town of Portsmouth.

In Portsmouth, he handled over 1,700 cases in ten years. He became one of New Hampshire's most important lawyers. He also helped revise the state's criminal laws.

During this time, the Napoleonic Wars affected America. Britain attacked American ships and forced American sailors to join their navy. President Thomas Jefferson responded with the Embargo Act of 1807, stopping trade with Britain and France. This hurt New England's economy, and Webster wrote against Jefferson's policies.

In 1812, the United States declared war on Britain, starting the War of 1812. Webster gave a speech on July 4, 1812, criticizing the war but warning against states leaving the Union. This speech was printed in newspapers across New England.

He was chosen as a delegate to the Rockingham Convention, which criticized President James Madison. Webster largely wrote the "Rockingham Memorial," which questioned the reasons for war and hinted at states leaving the Union. This document became famous for showing New England's opposition to the war. After the convention, he was nominated for the U.S. House of Representatives.

Congressman and Constitutional Lawyer

First Time in the House (1813–1817)

When Webster arrived in the House of Representatives in May 1813, the U.S. was struggling in the War of 1812. President Madison's party, the Democratic-Republicans, controlled Congress. Webster continued to criticize the war and opposed new taxes and a trade embargo. He became a respected speaker in the House. The war ended in early 1815 with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent.

After the war, President Madison wanted a Second Bank of the United States, protective tariffs (taxes on imported goods), and federal funding for public works. Webster supported a national bank but voted against the bill because he wanted the bank to remove certain paper money from circulation. He then helped pass a bill requiring government debts to be paid in gold, Treasury notes, or national bank notes.

Webster was in the middle on tariffs. He wanted tariffs to protect American factories but not so high that they hurt trade in New England. He decided not to run for another term in 1816 and moved to Boston for more profitable legal work.

A Leading Lawyer

Webster continued to practice law while in Congress. He argued his first case before the Supreme Court of the United States in 1814. He became nationally famous for his work on important Supreme Court cases. Between 1814 and 1852, he argued 223 cases and won about half of them. He also represented wealthy clients like John Jacob Astor.

Chief Justice John Marshall, a Federalist, led the Supreme Court. Webster became very good at making arguments that appealed to Marshall. He played a key role in eight major constitutional cases between 1814 and 1824. In cases like Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819) and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), the Supreme Court's decisions were based largely on his arguments. Marshall's famous quote, "the power to tax is the power to destroy," came from Webster's argument in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819). Because of his success, people called him the "Great Expounder and Defender of the Constitution."

In Dartmouth College v. Woodward, Webster represented his old college. The New Hampshire legislature tried to change Dartmouth into a state institution. Webster argued that the Constitution's Contract Clause protected the college's original agreement. The Supreme Court agreed, ruling in favor of Dartmouth. This decision set an important rule: corporations were independent of states and didn't have to justify their existence by serving public interest.

Webster remained active in politics even when not in Congress. He was a presidential elector and gave speeches against high tariffs. During President Monroe's time, there was less political fighting, known as the "Era of Good Feelings." In 1820, Webster voted for Monroe for president.

He was also a delegate to the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention. He argued that voting rights should be tied to property ownership, but the state constitution was changed to allow more people to vote. His performance at the convention boosted his reputation as a statesman. In December 1820, he gave a popular speech celebrating 200 years since the Mayflower landed at Plymouth Rock.

Second Time in the House (1823–1827)

In 1822, Boston leaders convinced Webster to run for the U.S. House of Representatives again. He won and returned to Congress in December 1823. He became chairman of the House Judiciary Committee. He tried to pass a bill to make it easier for Supreme Court justices to travel, but it didn't pass.

Webster gave speeches supporting the Greek fight for independence and criticizing the Tariff of 1824. He argued that high tariffs hurt farming and trade. He also defended federal funding for public works, saying roads helped unite the nation.

In the 1824 U.S. presidential election, the Democratic-Republicans split. No candidate won enough electoral votes, so the House of Representatives decided the election. Webster supported John Quincy Adams, seeing Andrew Jackson as unqualified. Webster helped Adams win the election.

In 1825, President Adams proposed a big plan for federal projects, based on Clay's American System. Many Democratic-Republicans opposed this, rallying around Jackson. Webster became a leader of the pro-Adams forces in the House. Adams's supporters became known as National Republicans. Webster, like many Federalists, supported the American System and protective tariffs. He also defended the rights of the Creek Indians against Georgia's land claims.

First Time in the Senate

Adams Administration (1827–1829)

In 1827, the Massachusetts legislature elected Webster to the United States Senate. He was unsure about leaving the House, where he had a lot of influence, but he accepted. He voted for the Tariff of 1828, which raised tariff rates. Before the 1828 U.S. presidential election, he worked with Clay to build the National Republican Party. Despite their efforts, Andrew Jackson defeated President Adams in the 1828 election.

Jackson Administration (1829–1837)

The "Second Reply to Hayne"

After Jackson became president, Webster opposed most of his policies. He strongly disagreed with John C. Calhoun's idea of nullification, which said states could ignore federal laws. In January 1830, during a debate, Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina argued for states' rights.

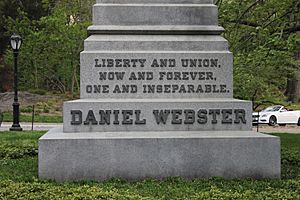

Webster spoke against Hayne, saying the U.S. was a "perpetual" union. He argued that the people, not the states, held the ultimate power, and the Constitution was the supreme law. He said nullification was "absurd" and would lead to civil war. He ended his speech with the famous words: "Liberty and Union, now and for ever, one and inseparable!" This speech, known as the Second Reply to Hayne, was reprinted widely and praised across the country.

The Bank War and 1832 Election

By 1830, Webster thought Clay would be the National Republican candidate for the 1832 U.S. presidential election. Some leaders of the Anti-Masonic Party tried to get Webster to run, but he didn't want to upset Clay. Instead, he tried to gain support for himself.

Webster urged Clay to join the Senate. Together, they convinced Nicholas Biddle, the head of the national bank, to ask for an early renewal of the bank's charter. They hoped to make the bank an issue in the 1832 election, knowing Jackson opposed it. Clay was nominated by the National Republicans, and Jackson was nominated for a second term.

Biddle asked for the bank's charter renewal in January 1832, starting the "Bank War." Webster led the pro-bank forces in the Senate. Congress approved the renewal, but Jackson vetoed the bill in July 1832. Jackson said the bank was unconstitutional and only helped the rich. Webster argued that only the courts could decide if a bill was constitutional. Jackson was re-elected by a large margin.

The Nullification Crisis

Even after Congress lowered tariffs with the Tariff of 1832, Calhoun and his allies were still unhappy. In South Carolina, a convention declared the Tariff of 1832 "null, void, and no law" in their state. This started the Nullification Crisis. Calhoun took Hayne's place in the Senate.

In December 1832, Jackson warned South Carolina that he would not let them defy federal law. Webster strongly supported Jackson's stance. He backed Jackson's proposed Force Bill, which would allow the president to use force against states that resisted federal law. Webster opposed Clay's efforts to lower tariffs further, believing it would set a bad example. After a debate between Webster and Calhoun, Congress passed the Force Bill in February 1833. Soon after, the Tariff of 1833 was passed, which gradually lowered tariffs. South Carolina accepted the new tariff, ending the crisis.

The Whig Party and 1836 Election

Jackson's opponents formed the Whig Party. This new party included National Republicans like Clay and Webster, as well as others. The Whig Party became one of the two major parties in the U.S.

Webster hoped to be the Whig candidate for president in the 1836 U.S. presidential election. However, General William Henry Harrison and Senator Hugh Lawson White had strong support in other regions. Whig leaders decided to run multiple candidates to try and force the election to be decided by the House of Representatives.

Webster was nominated by the Massachusetts legislature. But Harrison got most of the Whig support outside the South. Many Whigs hoped Harrison's military background would help him win, like Jackson had. Webster's chances were hurt by his past ties to the Federalist Party and his close connections to wealthy people. He was admired but not widely loved or trusted by the public.

Webster tried to withdraw from the race, but Massachusetts Whig leaders convinced him to stay. Martin Van Buren, Jackson's chosen successor, was nominated by the Democrats. In the 1836 election, Van Buren won. Webster only won the electoral votes from Massachusetts.

Van Buren Administration (1837–1841)

Soon after Van Buren became president, a major economic crisis called the Panic of 1837 began. Whigs blamed Jackson's policies, but a global economic downturn was also a cause. The panic caused financial problems for Webster, who had invested heavily in land. He would remain in debt after 1837.

Webster hoped to win the Whig nomination in the 1840 U.S. presidential election but decided not to challenge Clay or Harrison. He traveled to Europe, where he met Alexander Baring, 1st Baron Ashburton. While he was away, the Whigs nominated Harrison for president. Although some wanted Webster as vice president, John Tyler was chosen instead.

Webster campaigned for Harrison in the 1840 election. He didn't like the new, popular style of campaigning with songs and slogans. The Whigs won a big victory in 1840, with Harrison winning the presidency and the party gaining control of Congress.

Secretary of State in the Tyler Administration

Harrison consulted Webster and Clay on appointments. Harrison wanted Webster to be Secretary of the Treasury, but Webster chose to be Secretary of State, handling foreign affairs. Just one month after taking office, Harrison died, and John Tyler became president.

Tyler and Webster had different political ideas, but they initially worked well together. Webster urged Whig congressmen to support a compromise bill to re-establish the national bank. However, Congress rejected it and passed Clay's bill, which Tyler vetoed. After Tyler vetoed another bill, all Cabinet members except Webster resigned. Whigs then voted to remove Tyler from the party. Webster chose to stay, telling Tyler, "Henry Clay is a doomed man."

With a hostile Congress, Tyler and Webster focused on foreign policy. They emphasized American influence in the Pacific Ocean. They made the first U.S. treaty with China and tried to divide Oregon Country with Britain. They also announced that the U.S. would oppose any attempts to colonize the Hawaiian Islands.

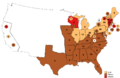

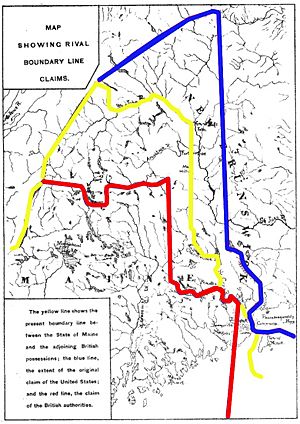

The most urgent foreign policy issue was relations with Britain. The two countries had almost gone to war over border disputes in Maine and Canada. British Prime Minister Robert Peel sent Lord Ashburton to the U.S. After long talks, the U.S. and Britain signed the Webster–Ashburton Treaty. This treaty clearly defined the border between Maine and Canada. The Senate approved the treaty.

After mid-1841, Whigs in Congress pressured Webster to resign. By early 1843, Tyler also wanted him to leave. As Tyler moved further away from Whig ideas, Webster left office in May 1843. With Webster gone, Tyler focused on the Texas annexation.

Webster's time in the Tyler administration hurt his standing with Whigs. However, he began to rebuild his alliances. Tyler's attempts to annex Texas became a key issue in the 1844 election. Webster strongly opposed annexation and campaigned for Clay, who was the Whig nominee. Despite Webster's efforts, James K. Polk defeated Clay.

Second Time in the Senate

Polk Administration (1845–1849)

Webster considered retiring after the 1844 election but accepted election to the Senate in early 1845. He tried to block Polk's policies, but Democrats controlled Congress. They lowered tariffs and re-established the Independent Treasury system.

In May 1846, the Mexican–American War began. Northern Whigs split into "Conscience Whigs," who strongly opposed slavery, and "Cotton Whigs" like Webster, who wanted good relations with the South. Webster had always been against slavery, calling it a "great moral, social, and political evil." However, he believed Congress should not interfere with slavery in existing states. He opposed gaining Mexican territory and voted against the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which acquired the Mexican Cession.

General Zachary Taylor's success in the war made him a leading Whig candidate for the 1848 U.S. presidential election. Clay and Webster also ran for president. Webster's standing was hurt by opposition from the Conscience Whigs. Taylor won the Whig nomination. Webster eventually supported Taylor, who won the election.

Taylor Administration (1849–1850)

Webster had only weakly supported Taylor's campaign, so he was not included in the new administration's Cabinet. After the 1848 election, the issue of slavery in the new territories became a major debate. In January 1850, Clay proposed a plan to solve these issues. His plan included admitting California as a free state, settling Texas's border claims, creating New Mexico and Utah territories, banning slave trade in Washington D.C., and a stricter fugitive slave law.

Webster supported Clay's plan. In his "Seventh of March" speech, Webster criticized both Northerners and Southerners for increasing tensions over slavery. He told Northerners to stop hindering the return of fugitive slaves but also criticized Southern leaders for talking about leaving the Union. Abolitionists in New England strongly criticized Webster after this speech.

The debate over Clay's compromise continued until July 1850, when President Taylor suddenly died.

Secretary of State in the Fillmore Administration

Millard Fillmore became president after Taylor's death. Fillmore dismissed Taylor's Cabinet and appointed Webster as his Secretary of State. Fillmore supported Clay's compromise plan. Webster became an important leader in the Cabinet.

After Fillmore took office, Senator Stephen A. Douglas led the effort to pass a compromise based on Clay's ideas. Webster helped the president by drafting a message to Congress, urging them to end the crisis. Soon after, Congress passed Douglas's plan, which became known as the Compromise of 1850.

The Compromise of 1850 became the main political issue during Fillmore's presidency. The most controversial part in the North was the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Webster became deeply involved in enforcing this law. Disputes over runaway slaves were widely publicized, increasing tensions. Many government attempts to return slaves failed. In Massachusetts, anti-slavery Whigs elected Free Soil leader Charles Sumner to the Senate, which was a major setback for Webster.

Opening of the New York & Erie Rail Road

In May 1851, when the New York & Erie Rail Road was finished, President Fillmore and Webster took a special two-day trip to open the railway. It is said that Webster watched the entire journey from a rocking chair on a flatcar. At stops, he would get off and give speeches.

Foreign Affairs

Fillmore chose Webster for his experience in foreign affairs. Webster guided the administration's foreign policy. After the failed Hungarian Revolution of 1848, there was a diplomatic issue with the Austrian Empire. The Fillmore administration helped release exiled Hungarian leader Lajos Kossuth and honored him.

The administration was very active in Asia and the Pacific, especially with Japan, which had strict rules against foreign contact. In November 1852, the administration launched the Perry Expedition to force Japan to open trade with the U.S. This mission was successful, and Japan agreed to trade in 1854. The Fillmore administration also made trade agreements with Latin American countries and worked to prevent unauthorized military expeditions against Cuba.

1852 Election

Webster launched another campaign for president in 1851, encouraged by Fillmore. Fillmore was sympathetic but didn't rule out running himself. General Winfield Scott also emerged as a candidate. Scott had supported the Compromise of 1850, but his ties to William H. Seward made him unacceptable to Southern Whigs. Southerners supported Fillmore, while most Northern Whigs preferred Scott. Webster only had support from a few delegates, mostly from New England.

At the 1852 Whig National Convention, Fillmore, Scott, and Webster all received votes. Although Webster and Fillmore were willing to step aside for each other, their delegates couldn't unite. Scott won the nomination on the 53rd ballot. Webster was very disappointed and refused to support Scott. Scott lost the election to Democratic nominee Franklin Pierce. Many anti-Scott Whigs voted for Webster.

Personal Life and Family

In 1808, Webster married Grace Fletcher, a schoolteacher. They had five children: Grace, Daniel "Fletcher", Julia, Edward, and Charles. Grace and Charles died young. Webster's wife, Grace, died in January 1828 from a tumor. His brother, Ezekiel, died in April 1829.

In December 1829, Webster married Caroline LeRoy, who was 32. They remained married until his death. They had two children together: another daughter named Grace and a son named Noah.

The Websters lived in Portsmouth until 1816, then moved to Boston. In 1831, Webster bought a large estate in Marshfield, Massachusetts. He spent much of his money improving this estate and made it his main home in 1837. He also owned his father's home in Franklin, New Hampshire.

Webster's older son, Fletcher, became a lawyer and worked for the State Department. He was the only one of Webster's children to outlive him. Fletcher died in 1862 during the Second Battle of Bull Run while serving as a colonel in the Union army. Webster's younger son, Edward, died of typhoid fever in January 1848 during the Mexican-American War. His daughter, Julia, died of tuberculosis in April 1848.

Webster was closely connected to the Congregational church throughout his life. He believed in the importance of faith and the Congregational way of worship.

Death

By early 1852, Webster's health was declining due to illness. In September 1852, he returned to his Marshfield estate, where his health continued to worsen. He died in Marshfield, Massachusetts, on October 24, 1852, at the age of 70. He is buried in Winslow Cemetery near his estate. His last words were: "I still live."

Legacy and Remembrance

Historians agree on Webster's powerful speaking skills, his great intelligence, and his deep knowledge of the Constitution. Ralph Waldo Emerson called him "the completest man." John F. Kennedy praised Webster's courage in supporting the Compromise of 1850, even though it risked his political future.

However, some historians note that Webster sometimes struggled with leadership. He was also known for his financial difficulties and expensive lifestyle. Despite this, his nationalistic view of the Union as "one and inseparable" helped strengthen the idea of a united country.

Webster is widely praised for his skills as a speaker and lawyer. His "Reply to Hayne" speech in 1830 was considered "the most eloquent speech ever delivered in Congress" for many years.

Memorials

Many things are named after Daniel Webster. These include the Daniel Webster Highway and Mount Webster in New Hampshire. His statue stands in the National Statuary Hall Collection in Washington D.C., and another statue is in Central Park in New York City.

Two ships, the USS Daniel Webster (SSBN-626) and the SS Daniel Webster, were named for him. He has been honored on 14 different U.S. postage stamps, more than most presidents. There are 27 towns and seven counties or parishes named for Webster across the United States.

In Media

Webster is the main character in a short story called The Devil and Daniel Webster by Stephen Vincent Benét. This story was also made into an opera and a film.

Webster has been played by several actors in movies, including:

- George MacQuarrie in The Mighty Barnum (1934)

- Edward Arnold in The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941)

- Anthony Hopkins in Shortcut to Happiness (2007)

Images for kids

-

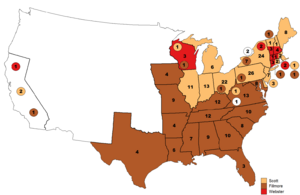

Through the Webster–Ashburton Treaty, Webster helped bring an end to a boundary dispute in Maine

-

Daniel Webster monument, Central Park, New York City, from the base: "Liberty and Union, Now and Forever, One and Inseparable"

See also

In Spanish: Daniel Webster para niños

In Spanish: Daniel Webster para niños

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Webster/Sainte-Laguë method

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |