Henry Clay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Clay

|

|

|---|---|

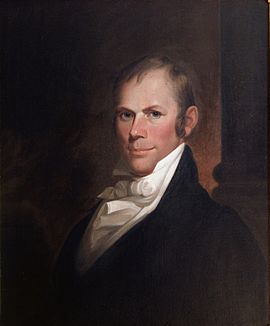

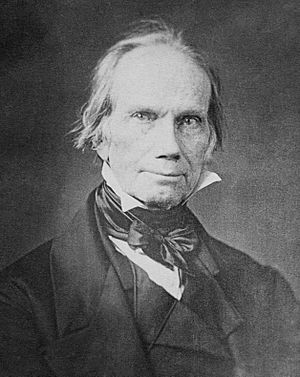

Clay photographed in 1848

|

|

| 9th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 4, 1825 – March 4, 1829 |

|

| President | John Quincy Adams |

| Preceded by | John Quincy Adams |

| Succeeded by | Martin Van Buren |

| United States Senator from Kentucky |

|

| In office March 4, 1849 – June 29, 1852 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Metcalfe |

| Succeeded by | David Meriwether |

| In office November 10, 1831 – March 31, 1842 |

|

| Preceded by | John Rowan |

| Succeeded by | John J. Crittenden |

| In office January 4, 1810 – March 3, 1811 |

|

| Appointed by | Charles Scott |

| Preceded by | Buckner Thruston |

| Succeeded by | George M. Bibb |

| In office December 29, 1806 – March 3, 1807 |

|

| Preceded by | John Adair |

| Succeeded by | John Pope |

| 7th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In office March 4, 1823 – March 3, 1825 |

|

| Preceded by | Philip P. Barbour |

| Succeeded by | John Taylor |

| In office March 4, 1815 – October 28, 1820 |

|

| Preceded by | Langdon Cheves |

| Succeeded by | John Taylor |

| In office March 4, 1811 – January 19, 1814 |

|

| Preceded by | Joseph Varnum |

| Succeeded by | Langdon Cheves |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky |

|

| In office March 4, 1823 – March 6, 1825 |

|

| Preceded by | John Johnson |

| Succeeded by | James Clark |

| Constituency | 3rd district |

| In office March 4, 1815 – March 3, 1821 |

|

| Preceded by | Joseph H. Hawkins |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Woodson |

| Constituency | 2nd district |

| In office March 4, 1811 – January 19, 1814 |

|

| Preceded by | William T. Barry |

| Succeeded by | Joseph H. Hawkins |

| Constituency | 2nd district (1813–1814) 5th district (1811–1813) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 12, 1777 Hanover County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | June 29, 1852 (aged 75) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (1797–1825) National Republican (1825–1833) Whig (1833–1852) |

| Spouse |

Lucretia Hart

(m. 1799) |

| Children | 11, including Thomas, Henry, James, John |

| Education | College of William & Mary |

| Signature |  |

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777 – June 29, 1852) was an important American lawyer and politician. He represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives. He served as the seventh House Speaker and the ninth Secretary of State.

Clay ran for president three times but did not win. He helped start two major political groups: the National Republican Party and the Whig Party. People called him the "Great Compromiser" because he helped solve big problems between different parts of the country. He was also part of the "Great Triumvirate" in Congress, along with Daniel Webster and John C. Calhoun.

Clay was born in Hanover County, Virginia, in 1777. He started his law career in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1797. As a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he was elected to the Kentucky state legislature in 1803. He then joined the U.S. House of Representatives in 1810.

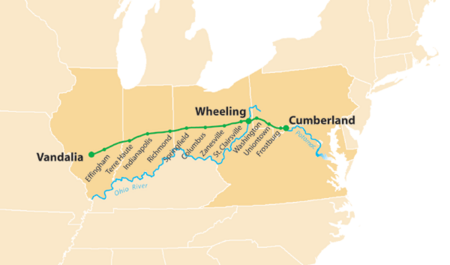

In 1811, he became Speaker of the House. He helped lead the United States into the War of 1812 against Great Britain. In 1814, he helped create the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the war. After the war, Clay returned as Speaker. He developed the American System, a plan for federal investments in roads and canals, a national bank, and high tariffs to protect American businesses. In 1820, he helped pass the Missouri Compromise, which dealt with the issue of slavery in new states.

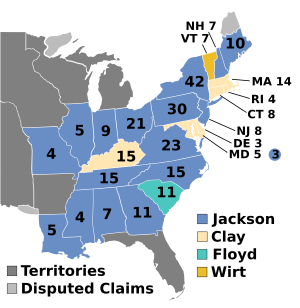

In the 1824 presidential election, Clay finished fourth. He then helped John Quincy Adams win the election in the House of Representatives. President Adams made Clay the Secretary of State. Critics called this a "corrupt bargain." Adams lost the 1828 election to Andrew Jackson.

Clay was elected to the Senate in 1831. He ran for president in 1832 but lost to President Jackson. After this, Clay helped end the nullification crisis by passing the Tariff of 1833. During Jackson's second term, Clay and others formed the Whig Party. Clay became a very important Whig leader in Congress.

Clay wanted to be president in 1840 but the Whigs chose William Henry Harrison. When Harrison died, his vice president, John Tyler, became president. Tyler disagreed with Clay and other Whigs. Clay left the Senate in 1842. He won the Whig presidential nomination in 1844 but lost to James K. Polk. Polk wanted to add Texas to the U.S.

Clay did not like the Mexican–American War. He tried to get the Whig nomination in 1848 but lost to General Zachary Taylor. After returning to the Senate in 1849, Clay helped pass the Compromise of 1850. This deal helped avoid a crisis over slavery in new territories. Henry Clay is seen as one of the most important politicians of his time.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, in Hanover County, Virginia. He was one of nine children. His father died when Henry was young, leaving his family in a difficult financial situation. His mother later remarried Captain Henry Watkins, who was a kind stepfather.

In 1791, his family moved to Kentucky. Henry stayed in Virginia to work in a store in Richmond. Later, he got a job as a clerk at the Virginia Court of Chancery. His good handwriting caught the eye of George Wythe, a judge and professor at the College of William & Mary. Wythe, who had a hand injury, chose Clay as his secretary. Clay worked for Wythe for four years. Wythe taught Clay about human freedom and how the United States could inspire the world. After this, Clay studied law with Virginia's attorney general, Robert Brooke. Clay became a lawyer in 1797.

Family Life

On April 11, 1799, Henry Clay married Lucretia Hart in Lexington, Kentucky. Her father, Colonel Thomas Hart, was a successful businessman. He helped Clay get new clients and become more respected as a lawyer. Henry and Lucretia were married until his death in 1852. They had eleven children.

In 1804, they started building their home, Ashland, outside Lexington. The Ashland estate grew to over 500 acres. It had many buildings, including a smokehouse and barns. Clay grew crops like corn, wheat, and hemp. He also loved thoroughbred racing and brought in special horses and other animals. Even though he faced some money problems, he always managed well and left a large inheritance for his children.

Early Career in Law and Politics

Becoming a Lawyer

In November 1797, Clay moved to Lexington, Kentucky. He quickly got a license to practice law in Kentucky. He learned from other lawyers and soon started his own law practice. He often worked on cases about debts and land. Clay became known for his strong legal skills and powerful speeches in court. In 1805, he taught at Transylvania University.

Starting in Politics

Clay entered politics soon after moving to Kentucky. He spoke out against the Alien and Sedition Acts, laws that limited free speech. Like most Kentuckians, Clay was a Democratic-Republican. He wanted elected officials in Kentucky to be chosen directly by the people. He also supported the idea of slowly ending slavery in Kentucky.

In 1803, Clay was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives. He worked to improve roads and canals, which became a main goal throughout his career. In 1806, the Kentucky legislature chose him to serve in the United States Senate. During his two months there, he pushed for building bridges and canals.

After returning to Kentucky in 1807, he became the speaker of the state house. He supported President Thomas Jefferson's Embargo Act of 1807, which limited trade with other countries. In 1809, Clay fought a duel with Humphrey Marshall, a political opponent. Both were shot but survived.

In 1810, Clay was chosen to fill a vacant U.S. Senate seat. He strongly criticized British attacks on American ships. He was part of a group called "war hawks" who wanted to go to war with Britain. He also supported adding West Florida to the U.S. Clay helped stop the First Bank of the United States from being re-approved, arguing it interfered with state banks. After one year, Clay decided he preferred the House of Representatives and was elected there in late 1810.

Speaker of the House of Representatives

Leading Congress

In 1811, Henry Clay was elected Speaker of the House. At 34, he was the youngest person to hold this job at the time. He was also the first new member of Congress to become Speaker.

Clay served seven terms in the House between 1810 and 1824. He was Speaker six times, making his time in office the second longest ever. As Speaker, Clay had a lot of power. He decided who would be on important committees. He also often spoke in debates, which was unusual for a Speaker. He was known for being fair and polite. Clay worked to make the Speaker's office more powerful, and President James Madison often let Congress lead.

War of 1812 and Peace Treaty

Clay and other "war hawks" wanted Britain to stop attacking American ships. Clay believed fighting Britain was the only way to protect American honor. He led the House in voting to declare war against Britain. President Madison signed the declaration on June 18, 1812, starting the War of 1812.

In 1813, President Madison asked Clay to join a team of diplomats to negotiate peace in Europe. Clay resigned from Congress in January 1814 to accept. Negotiations began in August 1814. Clay was one of five American representatives. He often disagreed with John Quincy Adams, another American diplomat. Clay was very upset by Britain's first peace offer. He believed Britain wanted peace badly because they were tired from fighting France. Partly because of Clay's firm stance, the Treaty of Ghent had good terms for the U.S. It basically returned things to how they were before the war. The treaty was signed on December 24, 1814, ending the War of 1812.

The American System

Clay returned to the U.S. in September 1815 and was re-elected Speaker. The War of 1812 made Clay believe even more in government-funded projects. He thought they were needed to improve the country's transportation. He supported President Madison's plans for infrastructure, tariffs to protect American businesses, and more money for the military.

With help from John C. Calhoun, Clay passed the Tariff of 1816. This tariff raised money and protected American factories. To make the country's money system stable, Clay helped create the Second Bank of the United States. Starting in 1818, Clay promoted his "American System." This plan included protective tariffs and investments in roads, canals, and other improvements.

Working with President Monroe

When President Madison retired, James Monroe became president in 1817. Monroe offered Clay the job of Secretary of War, but Clay wanted to be Secretary of State. He was upset when Monroe chose John Quincy Adams for that role.

In 1819, a debate started about whether Missouri should become a state. A proposal suggested slowly ending slavery in Missouri. Even though Clay had supported ending slavery in Kentucky before, he sided with the Southern states this time. He helped create the Missouri Compromise. This deal allowed Missouri to join as a slave state and Maine as a free state. It also banned slavery in new territories north of a certain line.

Clay was a strong supporter of independence movements in Latin America. He wanted the U.S. to recognize these new countries. In 1818, General Andrew Jackson entered Spanish Florida to fight Native Americans. Jackson also took over a Spanish town. Clay was very angry and publicly criticized Jackson. He compared Jackson to military dictators like Bonaparte. This started a long rivalry between Clay and Jackson.

The 1824 Presidential Election

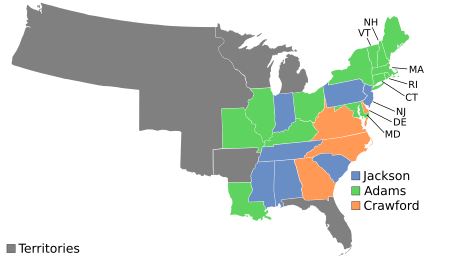

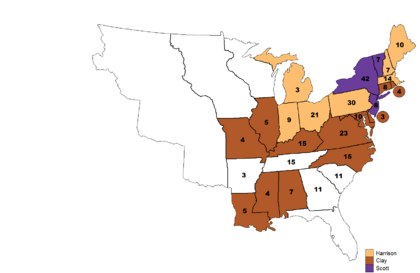

By 1822, several politicians wanted to become president after Monroe. The Federalist Party was almost gone, so only Democratic-Republicans ran in the 1824 election. Clay campaigned on his American System. Other main candidates were William Crawford, John Quincy Adams, and Andrew Jackson.

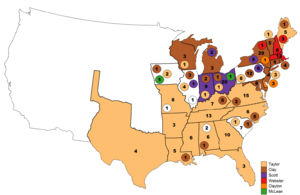

Clay believed no one would win enough electoral votes. If that happened, the House of Representatives would choose the president. Clay hoped he would win in the House, where he was Speaker. However, Clay finished fourth in the election, behind Adams, Jackson, and Crawford.

Clay decided to support Adams. He felt Adams was the most supportive of his American System. He also thought Jackson and Crawford were not suitable for president. With Clay's help, Adams won the House vote. Adams then offered Clay the job of Secretary of State, which Clay accepted. Jackson and his supporters were furious. They accused Clay and Adams of a "Corrupt Bargain," claiming they made a secret deal. This accusation became a major issue for Jackson's campaign in the 1828 election.

Secretary of State

Clay served as Secretary of State from 1825 to 1829. In this role, he was the main foreign policy official for President Adams. Clay and Adams became good friends. They both wanted to avoid making permanent alliances with other countries. They also continued to support the Monroe Doctrine, which warned European countries not to interfere in new Latin American nations.

Clay tried to make trade agreements with Britain and get France to pay for damages to American ships, but he was not successful. He had more success with Latin American countries, making trade deals that gave the U.S. equal trading rights. Clay wanted to send American delegates to the Congress of Panama to build stronger ties with Latin America, but the Senate stopped him.

President Adams proposed many domestic programs based on Clay's American System. However, many of Adams's ideas were defeated by his opponents in Congress. Still, Adams oversaw the building of important projects like the National Road and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.

Adams's supporters became known as National Republicans, and Jackson's supporters became Democrats. Both sides spread negative stories about each other. Clay was a key adviser to Adams, but his duties as Secretary of State kept him from campaigning much. In the 1828 election, Jackson won by a lot, even in Clay's home state of Kentucky. This was a big disappointment for Clay, as it rejected his policies.

Later Political Career

Facing President Jackson

Even after Clay left office, President Jackson still saw him as a major opponent. Clay strongly disagreed with the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which forced Native Americans to move west. Another big disagreement was over the Maysville Road project in Kentucky. Jackson vetoed it, saying it was not a federal responsibility. This hurt Jackson's support in Kentucky.

In 1831, Clay returned to federal office by winning election to the Senate. He had been out of the Senate for over 20 years.

The Bank War and 1832 Election

Clay became the leader of the National Republicans. He started preparing for the 1832 election. Jackson made it clear he would run again. The main issue became the national bank. By the 1830s, the Second Bank of the United States was very powerful. Jackson disliked the bank and paper money.

The bank's charter was set to expire in 1836, but the bank president asked for it to be renewed early. Congress passed a bill to renew the bank's charter, but Jackson vetoed it. He said the bank was unconstitutional. Clay had hoped this issue would help him win, but Jackson's supporters argued that the bank favored the rich. Clay lost the election to Jackson by a large margin.

Ending the Nullification Crisis

High tariffs in 1828 and 1832 angered many Southerners because they made imported goods more expensive. After the 1832 election, South Carolina declared these tariffs invalid within its state. This was called the Nullification Crisis. President Jackson said states could not ignore federal laws or leave the Union. He asked Congress to pass a "Force Bill" to use military force if needed.

Clay supported high tariffs, but he wanted to avoid a civil war. He proposed a compromise tariff bill that would slowly lower tariff rates. This gave businesses time to adjust. Clay's compromise bill passed Congress. Jackson signed both the tariff bill and the Force Bill. South Carolina accepted the new tariff, ending the crisis. Clay's role in solving this problem earned him the nickname "Great Compromiser."

Forming the Whig Party

After the Nullification Crisis, Jackson continued his fight against the national bank. He moved all federal money from the national bank to state banks. Many people thought Jackson's actions were illegal. Clay led the Senate in criticizing Jackson. The national bank's federal charter ended in 1836.

Jackson's opponents, including National Republicans and others, joined together to form the Whig Party. Clay gave a speech in 1834 comparing Jackson's opponents to the British "Whigs" who opposed absolute monarchy. Whigs generally wanted a stronger Congress, a stronger federal government, higher tariffs, more spending on infrastructure, and a national bank. Democrats wanted a stronger president, stronger state governments, lower tariffs, and expanding the country. Neither party took a strong national stance on slavery.

Clay did not run in the 1836 election. The Whigs were too disorganized and ran three different candidates against Martin Van Buren. Clay supported William Henry Harrison. Van Buren won the election.

Working with Van Buren

President Van Buren's time in office was hurt by the Panic of 1837, a major economic downturn. Clay and other Whigs blamed Jackson's policies for the panic. Clay promoted his American System as a way to fix the economy.

As the 1840 election neared, many expected the Whigs to win because of the economic crisis. Clay, Harrison, and Winfield Scott were the main Whig candidates. Many Whigs worried that Clay had lost two presidential elections already. They also had concerns about his slave ownership in the North and his moderate views on slavery in the South. Harrison won the Whig nomination. To balance the ticket, the Whigs chose John Tyler, a friend of Clay, as the vice-presidential candidate. Clay was disappointed but helped Harrison's successful campaign by giving many speeches.

Dealing with Presidents Harrison and Tyler

President Harrison asked Clay to be Secretary of State again, but Clay chose to stay in Congress. Harrison died just one month into his presidency. Vice President John Tyler became president. Tyler, a former Democrat, disagreed with Clay and the Whigs about re-establishing a national bank.

Clay and his allies in Congress tried to pass bills to create a new national bank. But Tyler vetoed two different bills. Clay and other Whig leaders were very angry. They felt Tyler had tricked them. Congressional Whigs voted to remove Tyler from the party. Most of Harrison's Cabinet members resigned, except for Daniel Webster. Clay became the clear leader of the Whig Party.

In 1842, Clay resigned from the Senate. Tyler did sign some Whig laws, like one that gave money from land sales to the states. He also signed a tariff law in 1842 that brought back protective rates.

The 1844 Presidential Election

With President Tyler no longer a Whig, Clay became the top choice for the Whig nomination in the 1844 election. President Tyler, hoping to win another term, pushed for the annexation of the Republic of Texas. This would add another slave state. Clay announced he was against annexation. He said the country needed "union, peace, and patience," and that annexation would cause problems over slavery and war with Mexico.

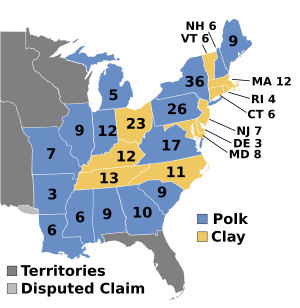

Clay won the Whig nomination easily. However, the Democrats chose James K. Polk, a "dark horse" candidate who supported annexing Texas. Polk was the first unexpected presidential nominee in U.S. history.

Clay was surprised by Polk's nomination but felt confident. Polk was a strong candidate who united the Democrats. Clay's stance on slavery upset some voters in both the North and the South. Pro-slavery Southerners liked Polk. Many Northern abolitionists voted for James G. Birney of the Liberty Party. Clay's opposition to annexation hurt him in the South.

Polk won the election by a small margin. Birney's votes in New York may have cost Clay the election. Most people at the time thought annexation was the main issue. After Polk's victory, Congress approved the annexation of Texas.

Later Years in the Senate

After the 1844 election, Clay went back to being a lawyer. He still followed national politics closely. In 1846, the Mexican–American War began. Clay did not publicly oppose the war at first. But privately, he thought it was wrong and could lead to a military leader taking too much power. He suffered a personal tragedy in 1847 when his son, Henry Clay Jr., died in the war.

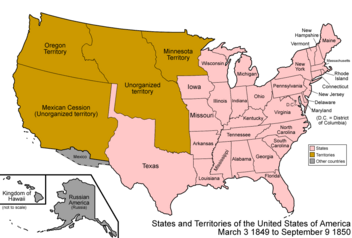

In November 1847, Clay spoke out against the Mexican–American War and President Polk. He criticized Polk for starting the conflict. He urged Congress to reject any treaty that would add new slave territory to the U.S. Months later, the Senate approved the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This treaty gave the U.S. a huge amount of land, known as the Mexican Cession.

By 1847, General Zachary Taylor, a war hero, was a top candidate for the Whig nomination in the 1848 election. Clay did not want to support Taylor, who was a "mere military man." On April 10, 1848, Clay announced he would run for the Whig nomination. Taylor won the nomination on the fourth ballot. Clay was disappointed and did not campaign for Taylor. However, Taylor still won the election.

The Compromise of 1850

Worried about growing tensions over slavery in the new territories, Clay returned to the Senate in 1849. In January 1850, Congress was stuck on what to do with the land from the Mexican–American War. Clay proposed a compromise to solve these problems.

His plan included:

- Admitting California as a free state.

- Texas giving up some land claims for debt relief.

- Creating the New Mexico and Utah territories.

- Banning the sale of slaves in Washington, D.C..

- A stricter fugitive slave law.

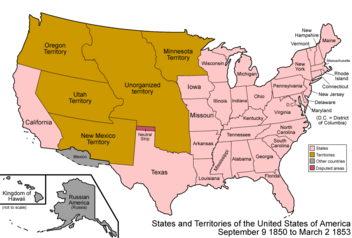

President Taylor opposed Clay's plan. Clay openly disagreed with the president in May 1850. In July, Taylor unexpectedly died. Vice President Millard Fillmore, who supported Clay's plan, became president. Clay took a break from the Senate due to his health. Fillmore, Daniel Webster, and Senator Stephen A. Douglas took over leading the effort to pass the compromise. By September 1850, Clay's plan, known as the Compromise of 1850, became law. Clay was seen as the key person who helped end this major crisis.

Death

In December 1851, at age 74, Clay's health was failing. He announced he would resign from the Senate the next September. Henry Clay died from tuberculosis on June 29, 1852, at age 75, in Washington, D.C. He was the first person to lie in state in the United States Capitol rotunda.

His headstone reads: "I know no North—no South—no East—no West."

Beliefs and Slavery

The American System

Throughout his political life, Clay promoted his American System. He saw it as a way to improve the economy and unite the country. Clay's American System believed in an active government that would help share economic benefits fairly.

The American System had four main parts:

- High tariffs: To make the U.S. less dependent on foreign goods.

- A stable financial system: Through a national bank that would regulate banking and provide credit.

- Federal investments: In roads, canals, and other transportation systems to connect the country.

- Public land sales: To raise money for states to invest in education and infrastructure.

Views on Slavery

Clay inherited slaves when he was young and owned slaves throughout his life. However, he also had anti-slavery views early in his career. He saw slavery as a "grievous wrong." He never called for slavery to end immediately. But he supported the idea of slowly ending slavery in Kentucky and Missouri. Both states rejected these plans. Clay continued to support gradual emancipation. In 1849, he wrote an open letter calling for it in Kentucky. He said it should include a plan to send free Black people out of the state.

In 1816, Clay helped start the American Colonization Society. This group wanted to create a colony in Africa for free Black Americans. The group included people who wanted to end slavery and slaveholders who wanted to remove free Black people from the U.S. Clay believed that a society with multiple races living together might not work.

Later, Clay worried about the extreme views on both sides of the slavery debate. He thought they threatened the country's unity. Still, he defended the right of abolitionists to send materials through the mail. He also opposed the "gag rule," which limited discussions about slavery in Congress.

Clay owned 122 enslaved people on his 600-acre plantation. He considered himself a "good" master. Some historians say he tried to keep families together. However, as Clay himself wrote, "here in Kentucky slavery is in its most mitigated form, still it is slavery." Clay's will arranged for the gradual freedom of the enslaved people he owned when he died in 1852. But he also gave some enslaved people to his son, John.

In 1829, one of Clay's enslaved people, Charlotte Dupuy, sued for her freedom. The case caused embarrassment for Clay. He won the case and sent Dupuy away from her family. However, he later freed Dupuy and two of her children.

Another enslaved person, Aaron Dupuy, Charlotte’s husband, was ordered to be whipped by Clay's wife. He fought back against the overseer. He was not freed when Clay died, but after the Civil War.

Some sources say Clay tried to keep families together, but other events show the opposite. Around 1836, Clay sold an enslaved mother, Esther Harvey, and her son to the South. They were the family of Lewis Hayden, who worked at a hotel. Around 1842, Clay threatened to sell Hayden's second wife, Harriet Bell Hayden, and her son. Hayden got help from others to escape through the Underground Railroad. The Haydens became residents of Amherstburg, Ontario, Canada.

Lewis Richardson, another enslaved person who escaped from Clay, gave a speech. He said that enslaved people at Ashland often had little food and warm clothing. He also described being whipped by an overseer. His speech was published in an abolitionist newspaper.

Legacy

Historical Importance

Henry Clay's political party, the Whigs, disappeared four years after he died. But Clay greatly influenced the leaders who dealt with the Civil War. Some believed that if Clay had been alive in 1860-1861, the Civil War might not have happened. Clay's student, John J. Crittenden, tried to keep the Union together with the Crittenden Compromise. Even though Crittenden's efforts failed, Kentucky stayed in the Union during the Civil War, partly because of Clay's lasting influence.

Abraham Lincoln greatly admired Clay, calling him "my ideal of a great man." Lincoln supported Clay's economic plans and had similar views on slavery and the Union before the Civil War. Some historians think that if Clay had won the 1844 election, the Mexican-American War and the Civil War might have been avoided.

Clay is considered one of the most important political figures of his time. Many historians believe he was one of the most influential Speakers of the House. In 1957, a Senate Committee named Clay one of the five greatest U.S. senators. A 1986 survey of historians ranked Clay as the greatest senator in U.S. history. Some historians even suggest calling his era the "Clay Era" instead of the "Jacksonian Era" because of his influence.

Monuments and Memorials

Many monuments, memorials, and even schools are named after Henry Clay. Sixteen counties across different states are named for him. Communities like Clay, Kentucky, and Claysville, Pennsylvania, also bear his name. The United States Navy named a submarine, the USS Henry Clay, in his honor. Several statues honor Clay, including one of Kentucky's two statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection. Clay's estate, Ashland, is a National Historic Landmark. The Decatur House, where Clay lived in Washington, D.C., as Secretary of State, is also a National Historic Landmark. A town in Liberia, West Africa, was named Clay-Ashland after Henry Clay. This was where freed enslaved people from Kentucky moved.

See also

In Spanish: Henry Clay para niños

In Spanish: Henry Clay para niños

- An Act for the Admission of the State of California

- List of slave owners

- List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)