Chesapeake and Ohio Canal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chesapeake and Ohio Canal |

|

|---|---|

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal at Lock 20

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 184.5 miles (296.9 km) |

| Maximum boat length | 90 ft 0 in (27.43 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 14 ft 6 in (4.42 m) |

| Locks | 74 (Boats must pass guard locks 4 & 5 for each trip.) |

| Status | National Park |

| History | |

| Original owner | Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company |

| Principal engineer | Benjamin Wright |

| Other engineer(s) | Charles B. Fisk, William Rich Hutton |

| Date of act | 1825 |

| Construction began | 1828 |

| Date of first use | 1830 |

| Date completed | 1850 |

| Date closed | 1924 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Georgetown, Washington DC (originally Little Falls, MD) (Canal extended down to Georgetown in 1830) |

| End point | Cumberland, MD (originally Sections to Pittsburgh, PA never built) |

| Connects to | Alexandria Canal (Virginia), Goose Creek & Little River Navigation |

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, often called the C&O Canal, was a waterway that operated from 1831 to 1924. It stretched along the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., to Cumberland, Maryland. The main thing carried on the canal was coal from the Allegheny Mountains.

Building this 184.5-mile (296.9 km) canal started in 1828. It was finished in 1850 when a 50-mile (80 km) section to Cumberland was completed. The canal rose and fell 605 feet (184 m) in elevation. This required building 74 canal locks. It also needed 11 aqueducts to cross big streams and over 240 culverts for smaller ones. A huge 3,118-foot (950 m) long Paw Paw Tunnel was also built. A plan to extend the canal to the Ohio River at Pittsburgh was never completed.

Today, the canal path is a Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. It has a trail that follows the old towpath, which is great for hiking and biking.

Contents

History of the C&O Canal

Early Waterway Ideas

After the American Revolutionary War, George Washington strongly believed in using waterways. He wanted to connect the Eastern Seaboard to the Great Lakes and the Ohio River. In 1785, Washington started the Potowmack Company. Its goal was to make the Potomac River easier to travel on. His company built five smaller canals around major waterfalls. These included Little Falls, Great Falls, and Harpers Ferry. These canals made it easier for boats to float downstream. Traveling upstream, by pushing with poles, was much harder.

Different types of boats were used on the Patowmack Canal. Gondolas were large rafts, about 60 by 10 feet (18 by 3 m). Their owners often sold them for wood at the end of a trip. Then they walked back upstream. Sharpers were flat-bottomed boats, 60 by 7 feet (18 by 2 m). They could only be used when the water was high, which was about 45 days a year.

Building the Canal: A Big Project

Planning the Route

The Erie Canal was built between 1817 and 1825. It made traders south of New York City worried. They started looking for their own ways to connect areas west of the Appalachian Mountains to eastern markets. As early as 1820, people began planning a canal to link the Ohio River and Chesapeake Bay.

In March 1825, President James Monroe signed a bill to build the C&O Canal. This was one of his last actions as president. The plan was to build it in two parts. The eastern part would go from Washington, D.C., to Cumberland, Maryland. The western part would cross the Allegheny Mountains to the Ohio River. The canal company did not have to pay taxes. It had to have 100 miles (160 km) of canal ready in five years. The whole canal needed to be finished in 12 years. The canal was designed for water to flow at 2 miles per hour (3.2 km/h). This helped supply the canal and assisted mules pulling boats downstream.

Only the eastern section was ever completed.

In October 1826, engineers shared their study. They showed the canal route in three sections. The eastern section was from Georgetown to Cumberland. The middle section went from Cumberland over the Allegheny Mountains. The western section continued from there to Pittsburgh. The total estimated cost was over $22 million. This was much more than many supporters expected. They thought it would cost around $4 million to $5 million.

Later, new estimates were given. In 1828, a report suggested $4.4 million for the Georgetown to Cumberland section. This encouraged stockholders to officially form the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company in June 1828. The final cost to build to Cumberland in 1850 was $11 million. This was higher than the first estimate, but it included things like land purchases and salaries.

In 1824, the Patowmack Company's assets were given to the Chesapeake and Ohio Company. The Maryland General Assembly allowed the Canal Company to raise $500,000. This helped get more investments and loans.

Starting Construction

The C&O's first chief engineer was Benjamin Wright, who had worked on the Erie Canal. A special ceremony was held on July 4, 1828, to start construction. U.S. President John Quincy Adams attended. The ceremony took place near Georgetown, at the canal's Lock 6.

There was some debate about where the canal should end in the east. Directors thought Little Falls was enough, as it met the charter's rule of reaching tidewater. But people in Washington wanted it to end in Washington, connecting to Tiber Creek. So, the canal first opened from Little Falls to Seneca in 1830. The next year, it was extended down to Georgetown.

The Little Falls skirting canal, which was part of the Patowmack Canal, was deepened. It became part of the C&O Canal.

The first president of the canal, Charles F. Mercer, wanted everything to be perfect. This made the company spend more money on building the canal. He did not allow using "slackwaters" (parts of the river used as part of the canal) for navigation. He also avoided certain types of locks or making the canal narrower in tough areas. This raised construction costs but saved money on future repairs. Eventually, two slackwaters and some "composite locks" (made of cheaper materials) were built.

At first, the company thought about using steamboats in the slackwaters. But without mules, canal boats had to use oars to move upstream. After many complaints, the company built a towpath. This allowed mules to pull the boats through the slackwaters.

Sections and Contracts

From Lock 5 at Little Falls to Cumberland, the canal was split into three divisions. Each division was about 60 miles (97 km) long. These were further divided into 120 sections, each about 0.5 miles (0.8 km) long. A separate contract was given for building each section. Locks, culverts, and dams were listed by section number.

Opening the First Parts

In November 1830, the canal opened from Little Falls to Seneca. The Georgetown section opened the following year.

Challenges and Expansion

In 1828, the C&O Canal and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) fought over land. They both wanted to use the narrow strip along the Potomac River from Point of Rocks to Harpers Ferry. After a court battle, they agreed to share the land.

In August 1829, the canal company started bringing in workers from other countries. These workers were promised food and pay. But many were unhappy with the tough conditions. Workers from Ireland and Germany had to be kept in separate groups to avoid arguments.

The canal was made narrower above Harpers Ferry to save money. This also made sense for engineering.

In 1832, a cholera epidemic spread through the construction camps. Many workers died, and others left.

By 1833, the canal's Georgetown end was extended eastward to Tiber Creek. This connected it to the Washington City Canal. A lock keeper's house from this time still stands near the National Mall.

In 1834, the section to Harpers Ferry opened. The canal reached Williamsport.

By 1839, the canal was near Hancock, Maryland. As it got closer, more building problems appeared. Limestone sinkholes caused parts of the canal bottom to collapse. Engineers had to make costly repairs.

Since good stone for locks was hard to find, engineers built "composite locks." These were made of cheaper stone and sometimes wood. The wood often rotted and had to be replaced. Later, some were lined with concrete.

In 1843, the Potomac Aqueduct Bridge was built. It connected the canal to the Alexandria Canal in Alexandria, Virginia.

In April 1843, floods damaged much of the canal. One flood stopped boats for 103 days. The company raised the banks in some areas to prevent future damage.

Finishing the Last Section

Building the last 50 miles (80 km) was hard and expensive. The final locks to Cumberland were finished around 1840. This left an 18.5-mile (29.8 km) section in the middle. It required building the famous Paw Paw Tunnel and digging a deep cut at Oldtown.

Near Paw Paw, engineers faced a big challenge. They decided to build a tunnel through the mountain. This was more expensive but avoided difficult river sections. The tunnel cost much more than expected. It took almost 12 years to build. A kiln was built to make bricks for the tunnel lining.

The canal was opened for trade to Cumberland on October 10, 1850. On the first day, five boats loaded with 491 tons of coal came down from Cumberland. The C&O carried more coal on its first day than the Lehigh Canal did in its entire first year (1820).

However, the B&O Railroad had already been operating in Cumberland for eight years. The canal struggled financially. The company stopped its plan to build the rest of the canal to the Ohio Valley. They realized building over the mountains to Pittsburgh was too difficult.

Even though the railroad reached Cumberland first, the canal was still useful. It wasn't until the mid-1870s that railroads, with better technology, could offer lower prices than the canal. This sealed the canal's fate.

Later Years and Closure

The canal suffered damage during the American Civil War. In 1869, the company reported that many structures were in bad shape. Still, some improvements were made in the late 1860s.

The early 1870s were very profitable for the canal. The company paid off some debts and made many improvements. They even installed a telephone system. But floods and other problems continued. By 1872, many boats were too old to be safe. The company started requiring yearly inspections.

For a short time, the company tried to stop boating on Sundays. But boatmen ignored the rule.

A trip from Cumberland to Georgetown usually took about seven days. The fastest known time for an empty boat was 62 hours.

End of Operations

After a terrible flood in 1889, the canal company went bankrupt. The B&O Railroad bought it. They did this mainly to keep the land from a rival railroad.

Over the next few decades, company-owned boats became more common. These boats were numbered instead of having colorful names.

The last known boat to carry coal returned to Cumberland on November 27, 1923. In 1924, only five boats carried sand for a power plant.

The 1924 Flood

The flood of 1924 caused huge damage to the canal. Many bridges were destroyed, and the canal banks were damaged. Although the railroad did some repairs, only the Georgetown section was fully fixed. This was to supply water to mills in Georgetown. The canal only operated for three months in 1924. After the flood, boats stopped using it. Some towns had also started dumping sewage into the canal. This made it a "public nuisance" and a breeding ground for mosquitoes.

After the 1924 flood, the railroad only repaired the Georgetown section. The rest of the canal remained broken. There was talk of reopening the canal in the late 1920s. But the Great Depression stopped these plans.

The boatmen, now without jobs, went to work for railroads, quarries, or farms.

The 1936 Flood

A winter flood in March 1936 caused even more damage. This flood was the highest the Potomac River had ever seen. It destroyed lockhouses and other structures. Some efforts were made to restore the Georgetown section for factories. But the rest of the canal became a "magnificent wreck." It needed a lot of repair and rebuilding.

Becoming a National Park

In 1938, the United States government took over the abandoned canal from the B&O Railroad. This happened in exchange for a loan. Today, it is the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park.

How the Canal Worked

Canal Size and Depth

The canal's size changed along its length. Below Lock 5, it was 80 feet (24 m) wide and 6 feet (1.8 m) deep. From Lock 5 to Harpers Ferry, it was 60 feet (18 m) wide and 6 feet (1.8 m) deep. Above Harpers Ferry, it was 50 feet (15 m) wide.

Locks and Water Control

The C&O Canal Company built 74 lift locks. These locks raised the canal from sea level at Georgetown to 610 feet (186 m) at Cumberland. Many locks and their houses were made from red sandstone from the Seneca Quarry. Riley's Lock (Lock 24) is special because it is also an aqueduct.

Seven "guard locks" or "inlet locks" were built. These allowed water and sometimes boats to enter the canal from the river.

Three other river locks were built to let boats enter the canal from the river. This was a condition for Virginia to buy canal stock. One was at Goose Creek, one near the Shenandoah River, and one at Shepherdstown. These river locks were eventually abandoned due to lack of use or damage.

At night, locktenders had to remove handles from the paddle valves. This was to stop people from using the locks without permission.

Composite Locks

Even though the canal's first president didn't want them, "composite locks" were built. These locks were made of cheaper stone and lined with wood. The wood protected the boats. But it often rotted and needed replacing. Later, some were lined with concrete.

Canal Levels

The section of canal between two locks is called a "level." Boatmen often named these levels by their length. For example, the longest was the "14 mile level." Waste weirs and bypass flumes helped control the water level in these sections.

Water Supply (Feeders)

Three streams were used to supply water to the canal: Rocky Run, Great Falls, and Tuscarora. The remains of the Potomac Company's Little Falls canal also served as a feeder.

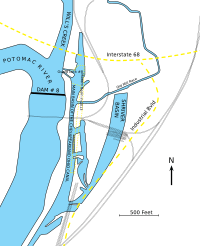

Two "slackwaters" were used for navigation: Big Slackwater and Little Slackwater. These were parts of the river where the canal boats could travel. Boats had to deal with winds, currents, and debris. At first, the company thought about using steam power here. But they decided to build a permanent towpath instead. This allowed mules to pull the boats.

Little Slackwater was especially tricky to navigate. It had sharp turns and a narrow strip of land. If the river current was fast, it could make steering very difficult. There are stories of towlines breaking and people having to escape.

Boatmen found it easier to navigate in slackwaters than in aqueducts. In aqueducts, there was less room for the water to move around the boat. This made it harder for mules to pull the boat.

Controlling Water Levels

[[multiple image | width = 150 | image1 = Waste_Weir_Closed_on_C_and_O_Canal.jpg | alt1 = Waste Weir | caption1 = A waste weir, looking from above. | image2 = Spillway_on_C_and_O_Canal.jpg | alt2 = A spillway | caption2 = A spillway ]] To control the water level in the canal, "waste weirs," "spillways," and "informal overflows" were used.

Waste weirs let out extra water from storms or when a lock was emptied. Boards could be added or removed to adjust the water level. They also had valves to drain the canal for repairs.

Spillways are concrete structures that let high water flow out of the canal. The longest spillway, near Chain Bridge, is 354 feet (108 m) long.

An informal overflow or mule drink was a dip in the towpath. Water would flow over it, like a spillway, but without concrete. Boatmen called these "mule drinks."

Paw Paw Tunnel

The Paw Paw Tunnel is one of the most impressive parts of the canal. It runs for 3,118 feet (950 m) under a mountain. It was built to save 6 miles (9.7 km) of construction around cliffs. The tunnel used over six million bricks. It took almost 12 years to build. The tunnel was only wide enough for one boat at a time. There's a story about two captains who refused to move. A company official smoked them out by burning cornstalks at one end of the tunnel.

Inclined Plane

An canal inclined plane was built about 2 miles (3.2 km) from Georgetown. This allowed boats going past Washington to avoid busy areas in Georgetown. The first boat used it in 1876. It was originally powered by a water turbine, then by steam. The inclined plane was taken apart after a major flood in 1889.

Telephone System

In the late 1870s, the company installed a telephone system. It cost $15,000 and had 43 stations along the canal. It was divided into sections with switches at different dams.

Culverts and Aqueducts

To carry small streams under the canal, 182 culverts were built. These were usually made of stone. For example, culvert #30 was built in 1835 for Muddy Branch. Culverts could collapse due to tree roots or get blocked by trash.

Eleven aqueducts carried the canal over larger rivers and streams.

Canal Repairs

The canal company hired "level walkers." These workers walked along the canal with shovels, looking for leaks and fixing them. Big leaks were reported to a supervisor, who would send a crew with a repair boat.

Boatmen believed that crabs and muskrats caused leaks. The company even paid a 25-cent reward for each muskrat caught.

Boats and Life on the Canal

The canal boats were designed to fit the locks. They were about 14.5 feet (4.4 m) wide and 90 feet (27 m) long. They could carry up to 130 tons of cargo. Passenger boats were also planned, pulled by four horses at 7 miles per hour (11 km/h).

Different types of boats were used:

- Packet Boats: For carrying passengers.

- Freight boats: For carrying goods.

- Scows: Work boats for construction and maintenance, and breaking ice.

- Gondolas: Flat-bottomed boats, sometimes used for temporary purposes.

Farmers sometimes built boats just for one trip. They would transport their goods and then sell the boat for firewood in Georgetown.

After the canal opened to Cumberland in 1851, new boat classes were introduced. These depended on size and how much cargo they could carry.

In later years, most boats carried coal. In 1875, 283 boats were owned by coal companies. Coal was loaded in Cumberland by dumping it from railroad cars into the boats. The crew would then clean the boat to remove dust.

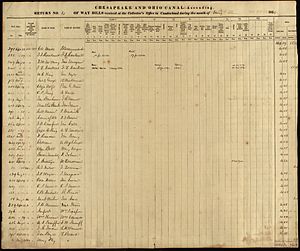

Tolls were charged for cargo. For example, in 1851, coal cost ¼ cent per ton per mile. Tolls changed often. Some boatmen tried to hide extra cargo to avoid paying tolls.

The canal carried many different goods. Before it was finished in 1845, it transported flour, wheat, corn, and lumber downstream. Upstream, it carried salt, plaster, and bricks.

After 1891, the canal mainly carried coal. It also transported limestone, wood, sand, and flour. Coal was loaded in Cumberland. The crew would scrub the boat clean after loading.

Coal was unloaded in Georgetown. Some was taken to coal yards, and some was loaded onto ocean ships.

One unusual load was a circus with a black bear. The bear got loose during the trip!

Other loads included furniture, pianos, watermelons, and fish. Boats also carried supplies for lockkeepers in remote areas. Cement, wood, and grain were also transported. Upstream loads included empty barrels, lumber, fertilizer, and even extra mules.

The company issued fines for breaking rules. For example, traveling without a waybill or damaging canal property.

The last coal boat operated in 1923. In 1924, only a few boats carried sand.

Boat Repairs

Boats carried tools like oakum and chisels to patch leaks. There were also special drydocks for repairs. The boat would sit on raised beams as the water was drained. Then, workers could fix it using tin and tar.

Icebreakers

Icebreakers were used to clear ice from the canal. This allowed the last boats to go home at the end of the season. An icebreaker was usually a company boat filled with heavy metal. Mules would pull it onto the ice, and its weight would break the ice. During the Civil War, icebreakers were used to keep the canal open for military supplies.

Mules: The Canal's Engines

Most boats were pulled by mules. Mules usually lasted about 15 years. They were often changed at locks using gangplanks. Some boatmen made mules swim to shore to change teams, which sometimes led to drownings. Mules were bought young, often from Kentucky. They were trained by dragging logs. The command to stop mules was "ye–yip–ye."

Getting a loaded boat moving was hard for the mules. They often had to work very hard, especially in Cumberland where there was no water current to help. Mules were shod every other trip in Cumberland. They were harnessed one behind the other, which helped pull the boat straighter.

"Drivers" were the people, often kids, who guided the mules on the towpaths. They were not called "muleskinners" or "hoggees" on the C&O Canal.

Dogs were helpful to boat captains. They could drive mules and even swim to help hitch the towline. One dog hunted muskrats, and the boatman sold their pelts. There are also stories of cats and even a raccoon on canal boats.

Steamboats on the Canal

Occasionally, steamboats were used. In 1850, the N S Denny company operated some steam-driven tugboats. Records from 1879 show a steamboat could travel about 3.25 miles per hour (5.2 km/h) loaded downstream. It used about a ton of coal per day.

Canal Families

Boatmen and their families were a unique group. They often married within their own community. They frequently argued with each other, sometimes over who got to use a lock first. They also argued with lockkeepers about company rules. In winter, when the canal froze, they often lived in their own communities. One captain said that women and children were as important as the men on the canal.

One time, a boat damaged another boat loaded with flour while trying to get through a lock. The flour had to be moved, but it wasn't damaged.

Recklessness was common among boatmen. Many accidents happened because boats went too fast. Aqueduct #3 had a sharp bend, causing many collisions.

Many boatmen said they knew no other life. One woman said, "The children are brought up on the boat and don't know nothin' else, and that is the only reason they take up 'boating'."

Daily Life and Work

Boatmen worked long hours, often 15 to 18 hours a day. They said, "It never rains, snows, or blows for a boatman, and a boatman never has no Sundays."

Captains were paid per trip, earning about $70 to $80 in the 1920s. Deck hands earned $12 to $20 per trip. The boating season usually ran from March to December. The canal was drained in winter for repairs and to prevent ice damage.

Women and Children on Boats

Women on the canal handled household chores and steered boats. They even gave birth on the boats, though they tried to find a midwife if near a town. If a husband died, the widow often continued to manage the boat. Women also worked as locktenders. One mother had 14 children, all born on boats, without a doctor.

Children often drove the mules. The U.S. Department of Labor noted that only physical strength limited what children could do. One man saw a ten-year-old girl put a boat through a lock. In wet weather, the towpath was muddy, and shoes wore out fast. One father provided his boys with rubber boots.

One boatman said, "A boat is a poor place for little children." His son missed many days of school because the family needed his help on the boat.

Food and Living Quarters

Canned food was sometimes brought on board. Bean soup with ham hocks and onion was common. Other foods included corn bread, eggs, bacon, ham, potatoes, and vegetables. Boatmen sometimes picked berries along the towpath. They also ate muskrats, chickens, ducks, rabbits, and fish caught in the canal.

Cabins were small, about 10 by 12 feet (3 by 3.7 m). They had two bunks, often shared by two people. The cabins were divided into sleeping areas and a "stateroom." The feed box for the mules often served as an extra sleeping spot.

Cooking was done on a stove, burning corncobs or coal. Washing clothes and children was usually done at night by the canal. Food supplies were bought in Cumberland. Some boatmen kept chickens or pigs on their boats.

Canal Legends and Stories

Many interesting stories and legends come from the canal's operating days:

- On the 9-mile level, around the 33–34 mile mark, some boats carried soldiers during the American Civil War. One boat sank, and people said the ghosts of soldiers haunted the area. Boatmen avoided tying up there at night. It was also called "Haunted House Bend."

- There was a story of an Indian chief's ghost on the 14-mile level near Big Pool.

- A lady ghost was reported on the 2-mile level at Catoctin. She would walk over the waste weir and down to the river.

- A headless man was said to haunt the Paw Paw Tunnel.

- A story like Romeo and Juliet was told near Lock 69.

- People believed there was "buried treasure" somewhere between Nolands Ferry and the Monocacy River. It could be found by following the ghost of a robber. He was supposedly seen on moonless nights crossing the Monocacy Aqueduct with a lantern.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Canal Chesapeake-Ohio para niños

In Spanish: Canal Chesapeake-Ohio para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |