Cholera facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cholera |

|

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Asiatic cholera, epidemic cholera |

|

|

| A person with severe dehydration due to cholera, causing sunken eyes and wrinkled hands and skin. | |

| Symptoms | Large amounts of watery diarrhea, vomiting, muscle cramps |

| Complications | Dehydration, electrolyte imbalance |

| Usual onset | 2 hours to 5 days after exposure |

| Duration | A few days |

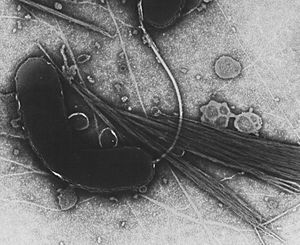

| Causes | Vibrio cholerae spread by fecal-oral route |

| Risk factors | Poor sanitation, not enough clean drinking water, poverty |

| Diagnostic method | Stool test |

| Prevention | Improved sanitation, clean water, hand washing, cholera vaccines |

| Treatment | Oral rehydration therapy, zinc supplementation, intravenous fluids, antibiotics |

| Prognosis | Less than 1% mortality rate with proper treatment, untreated mortality rate 50-60% |

| Frequency | 3–5 million people a year |

| Deaths | 28,800 (2015) |

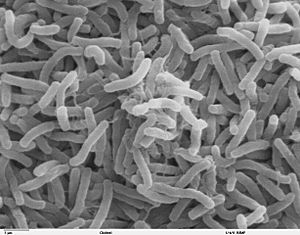

Cholera is a serious infection that affects your small intestine. It's caused by a type of germ called Vibrio cholerae.

Symptoms can be very mild, or they can be very severe. The main symptom is a lot of watery diarrhea that lasts for a few days. You might also feel sick to your stomach and throw up, or get muscle cramps.

This diarrhea can be so bad that it quickly leads to severe dehydration. This means your body loses too much water. When you're very dehydrated, your eyes might look sunken, your skin can feel cold, and your hands and feet might get wrinkly. Sometimes, your skin can even turn a little blue. Symptoms usually show up between two hours and five days after you're exposed to the germ.

Cholera spreads mostly through unsafe water and food that has been contaminated with human feces (poop) containing the bacteria. Eating undercooked shellfish is a common way to get it. People are the only known hosts for this germ. Things that increase your risk include poor sanitation, not enough clean water, and poverty. Doctors can diagnose cholera with a stool test.

To prevent cholera, it's important to have good sanitation and access to clean water. There are also cholera vaccines you can take by mouth. These vaccines offer good protection for about six months.

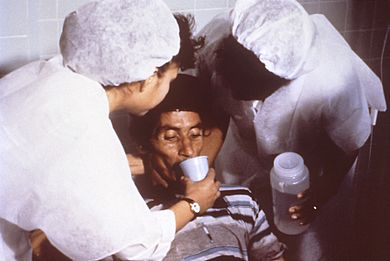

The best way to treat cholera is with oral rehydration therapy (ORT). This means drinking special salty and sweet solutions to replace lost fluids and body salts. In serious cases, doctors might need to give fluids through a vein. Antibiotics can also help.

Cholera affects millions of people worldwide each year. It causes many deaths, especially in developing countries. If treated properly, less than 1% of people die from cholera. But without treatment, the death rate can be as high as 50-60%.

Contents

What are the signs of cholera?

The main signs of cholera are a lot of diarrhea and vomiting clear fluid. These symptoms usually start quickly, from half a day to five days after you get the bacteria. The diarrhea often looks like "rice water" and might smell fishy.

A person with severe cholera can lose 10 to 20 liters (about 2.6 to 5.3 US gallons) of fluid a day. If this severe diarrhea isn't treated, it can lead to dangerous dehydration. This is why cholera has been called the "blue death." Your skin can turn bluish-gray from losing so much fluid.

Fever is rare with cholera. If you have a fever, it might mean you have another infection. People with cholera can feel tired and have sunken eyes, a dry mouth, cold skin, or wrinkled hands and feet. Their blood pressure can drop, and their heart might beat very fast. They will also pee less. Muscle cramps, weakness, confusion, or even seizures can happen, especially in children.

What causes cholera?

How does cholera spread?

Cholera bacteria have been found in shellfish and tiny sea creatures called plankton.

Cholera usually spreads when people eat or drink contaminated food or water. This contamination happens because of poor sanitation, meaning human waste gets into the water or food supply. In richer countries, food is often the source. In developing countries, it's more often water.

For example, people can get cholera from seafood like oysters if they are harvested from waters with sewage. This is because Vibrio cholerae can build up in plankton and oysters eat the plankton.

People with cholera have very watery diarrhea. If this "rice-water" stool gets into water used by others, the disease can spread. Just one diarrheal event can release millions of cholera germs into the environment. Drinking contaminated water or eating food washed in it can cause infection. Cholera rarely spreads directly from person to person.

The cholera germ can also live in natural water sources without human poop. Drinking this water can also cause the disease.

Who can get cholera?

Normally, a healthy adult needs to swallow about 100 million cholera bacteria to get sick. But this number is lower for people with less stomach acid. Young children are also more likely to get sick, especially those aged two to four.

Your blood type can also affect your risk; people with type O blood are most likely to get cholera. People with weak immune systems, like those with HIV/AIDS or who are malnourished, are more likely to get a severe case.

How does cholera make you sick?

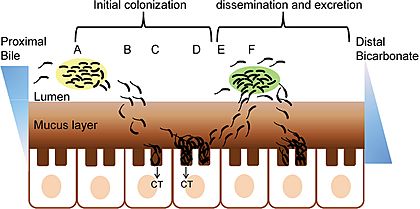

When you swallow cholera bacteria, most of them don't survive the strong acid in your stomach. The few that do survive save their energy as they pass through the stomach.

When these surviving bacteria reach your small intestine, they move through the thick mucus lining. They need to reach the walls of the intestine to attach and grow.

Once the cholera bacteria attach to the intestinal wall, they start making harmful substances called toxins. These toxins cause the watery diarrhea that makes people sick. This diarrhea helps spread the bacteria to new water sources and other people if sanitation is poor.

The main toxin, called cholera toxin (CTX), causes your body to pump water and salts into your small intestine. This creates a very salty, watery environment. This process can pull up to six liters of water per day from your body into your intestines. This is what causes the huge amounts of diarrhea and rapid dehydration.

Scientists have studied how these bacteria turn on and off the production of these toxins. They found that the bacteria react to the different chemical environments in your stomach and intestines. This helps them know when to start making the toxins that cause diarrhea.

How is cholera diagnosed?

There's a quick dipstick test that can tell if V. cholerae is present. If the test is positive, more tests might be done to see which antibiotics will work best.

During an epidemic, doctors can often diagnose cholera based on a patient's symptoms and history. Treatment with rehydration can start right away, even before lab tests confirm it.

Stool samples taken early in the illness, before antibiotics are given, are best for lab diagnosis.

How can we prevent cholera?

The World Health Organization (WHO) says it's important to focus on preventing cholera. They also stress having good plans for outbreaks and quick responses. Governments play a big role in all these areas.

Clean water and sanitation

Cholera can be life-threatening, but preventing it is usually simple if good sanitation is followed. In developed countries, cholera is rare because they have advanced water treatment and sanitation. For example, the last big cholera outbreak in the United States was over 100 years ago.

Cholera is mainly a risk in developing countries. This is where access to clean water, good sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) is still not enough.

Good sanitation can stop an epidemic. Here are some ways to stop cholera from spreading:

- Cleaning: Properly clean and dispose of anything that might have touched the poop of someone with cholera. This includes clothes and bedding. Wash them in hot water, using chlorine bleach if possible. Always wash your hands thoroughly after touching cholera patients or their belongings.

- Waste Management: In areas with cholera, human waste (sewage and fecal sludge) must be treated carefully. This stops the disease from spreading through poop. Untreated sewage should not be released into the environment.

- Water Warnings: Warnings should be put up near contaminated water sources. These warnings should explain how to make the water safe to use, like by boiling or adding chlorine.

- Water Purification: All water used for drinking, washing, or cooking should be cleaned. You can do this by boiling, adding chlorine, or using special filters. Boiling and chlorination are often the cheapest and most effective ways. Simple cloth filters, like folded sari cloth, have also helped reduce cholera in poor villages.

Washing hands with soap or ash after using the toilet and before handling food is also important for preventing cholera.

-

A special dry toilet in Haiti helps stop cholera from spreading through water.

-

A cholera hospital in Dhaka, showing typical "cholera beds."

Tracking outbreaks

Quickly tracking and reporting cholera cases helps stop epidemics fast. Cholera often happens seasonally in many countries, usually during rainy seasons. Tracking systems can give early warnings of outbreaks. This helps with a quick response and planning. Knowing when and where outbreaks happen helps guide efforts to control cholera for those most at risk.

Vaccines for cholera

The first human cholera vaccine was developed in 1892 by Waldemar Haffkine.

People who survive cholera usually have strong protection against it for at least three years. There are several safe and effective oral (taken by mouth) cholera vaccines. The WHO recommends three main oral cholera vaccines: Dukoral, Sanchol, and Euvichol. Dukoral is about 52% effective in the first year and 62% in the second year.

The WHO suggests using oral cholera vaccines in areas where the disease is common. They also recommend them during outbreaks or humanitarian crises where the risk of cholera is high. Vaccines are an important tool to help prevent and control cholera.

Sari cloth filters

In Bangladesh, a simple and cheap method called the "sari filter" helps clean drinking water. You fold a used sari cloth four to eight times. Used cloth works better than new cloth because repeated washing makes the fibers closer together.

Water filtered this way has far fewer germs. While it might not be perfectly safe, it's a big improvement for people with few other options. In Bangladesh, this practice cut cholera rates by almost half. After each use, the cloth should be rinsed in clean water and dried in the sun to kill any bacteria.

How is cholera treated?

Eating normally helps your intestines recover faster. The WHO recommends this for all types of diarrhea. For babies with watery diarrhea, it's important to keep breastfeeding, even when getting treatment. Adults and older children should also keep eating often.

Fluids for rehydration

The most common mistake in treating cholera is not giving enough fluids, fast enough. In most cases, cholera can be treated successfully with oral rehydration therapy (ORT). This means drinking special salty and sweet solutions. Solutions made with rice are often better than those with glucose.

For very severe cases, fluids might need to be given through a vein (intravenous rehydration). Large amounts of fluid are needed and must be replaced until the diarrhea stops. A person might need to receive 10% of their body weight in fluid within the first few hours. Fruit juices and sugary fizzy drinks are not good for rehydration. Their high sugar content can even make things worse.

If you can't get ready-made oral rehydration solutions, you can make one. A simple recipe is 1 liter of boiled water, 1/2 teaspoon of salt, 6 teaspoons of sugar, and mashed banana for potassium and taste.

Body salts (electrolytes)

When you have cholera, you lose a lot of important body salts, like potassium. Even if your potassium level seems normal at first, it can drop quickly as you get rehydrated. So, it's important to replace potassium. You can do this by eating foods high in potassium, like bananas or drinking coconut water.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics can shorten the illness and make symptoms less severe. They also reduce how much fluid you need. However, people can recover without antibiotics if they stay well hydrated. The WHO only suggests antibiotics for those with severe dehydration.

Doxycycline is often the first choice, but some types of V. cholerae are resistant to it. Testing for resistance during an outbreak helps doctors choose the right antibiotic. Other effective antibiotics include erythromycin and tetracycline.

Zinc supplements

In Bangladesh, giving zinc supplements to children with cholera helped reduce how long their diarrhea lasted and how severe it was. It shortened the illness by eight hours and reduced the amount of diarrhea. Zinc also seems to help treat and prevent other types of infectious diarrhea in children in developing countries.

What is the outlook for cholera?

If people with cholera are treated quickly and properly, less than 1% die. But if cholera is not treated, the death rate can go up to 50–60%.

For some types of cholera, like the one in Haiti in 2010, death can happen within just two hours of getting sick.

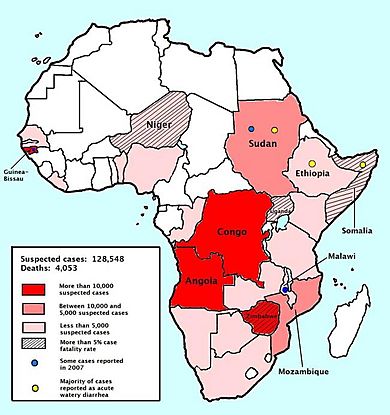

Where does cholera happen?

Cholera affects about 2.8 million people worldwide each year and causes around 95,000 deaths. This mostly happens in developing countries.

It's hard to know the exact number of cases because many go unreported. Countries might not report outbreaks due to worries about how it could affect tourism. Cholera is still common in many parts of the world.

Recent large outbreaks include the one in Haiti and the Yemen cholera outbreak. In 2019, most reported cholera cases were from Yemen.

Even though we know a lot about how cholera spreads, scientists don't fully understand why outbreaks happen in some places and not others. Lack of proper human waste treatment and unclean drinking water greatly help it spread. Water bodies can also hold the infection, and seafood shipped long distances can spread the disease.

Cholera disappeared from the Americas for most of the 20th century. But it came back in the late 1900s, starting with a big outbreak in Peru. It then appeared in Haiti. As of 2021, the disease is common in Africa and parts of Asia (like Bangladesh, India, and Yemen). Cholera is not common in Europe; all reported cases there were from people who had traveled to areas where cholera is common.

History of cholera outbreaks

The word "cholera" comes from a Greek word meaning "bile." Cholera likely started in India and has been there for centuries.

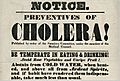

Early outbreaks in India probably happened because of crowded, poor living conditions and still water. These conditions are perfect for cholera to grow. The disease first spread by travelers along trade routes to Russia in 1817. Then it went to the rest of Europe, and from Europe to North America and other parts of the world. This is why it was sometimes called "Asiatic cholera."

Seven major cholera pandemics have happened since the early 1800s. The first one started in India in 1817. British Army and Navy ships helped spread the disease around the Indian Ocean, to Africa, Indonesia, China, and Japan.

The second pandemic (1826-1837) especially affected North America and Europe. Better transportation and more global trade meant the disease spread more widely.

The third pandemic (1846-1860) reached North Africa, North America, and South America. Brazil was affected for the first time.

The fourth pandemic (1863-1875) spread from India to Europe and reached the United States in New Orleans in 1873. It then spread along the Mississippi River.

The fifth (1881-1896) and sixth (1899-1923) pandemics had fewer deaths. This was because doctors and researchers understood the cholera bacteria better.

The seventh pandemic started in 1961 in Indonesia. A new type of cholera, called El Tor, appeared and is still around today. This pandemic was thought to have ended around 1975, but cases have risen again since the 1990s.

Cholera became very common in the 1800s. Since then, it has killed tens of millions of people. In Russia alone, over one million people died from cholera between 1847 and 1851. It killed 150,000 Americans during the second pandemic.

John Snow, a doctor in England, was the first to realize in 1854 that contaminated water was causing cholera. He is often called the "Father of Epidemiology" (the study of how diseases spread).

Today, cholera is not a big health threat in Europe and North America. This is thanks to filtering and chlorinating water supplies. But it still strongly affects people in developing countries.

In the past, ships with cholera cases would fly a yellow flag. No one from the ship was allowed ashore for a long time, usually 30 to 40 days.

Historically, people had many folk remedies for cholera. Some believed it was caused by bad air. Others thought getting a cold stomach made you sick. The first effective human vaccine was developed in 1885, and the first effective antibiotic in 1948.

-

Emperor Pedro II of Brazil visiting people with cholera in 1855.

Research on cholera

John Snow made a huge contribution to fighting cholera. In 1854, he found a link between cholera and contaminated drinking water. He showed that human sewage in water was causing major outbreaks in London. His work helped create the science of epidemiology.

The bacterium causing cholera was first found in 1854 by Filippo Pacini. In 1883, Robert Koch identified V. cholerae under a microscope.

Between the mid-1850s and the early 1900s, cities in developed countries invested a lot in clean water and separate sewage systems. This got rid of the threat of cholera epidemics in these cities.

A scientist named Hemendra Nath Chatterjee was the first to show that oral rehydration salt (ORS) could treat diarrhea. In 1953, he published that a mix of salt, glucose, and water could help.

Sambhu Nath De, an Indian medical scientist, discovered the cholera toxin. He also showed how the cholera germ is transmitted.

Global plan to end cholera

In 2017, the WHO launched a plan called "Ending Cholera: a global roadmap to 2030." This plan aims to reduce cholera deaths by 90% by 2030. The plan combines tracking outbreaks, improving water sanitation, providing rehydration treatment, and using oral vaccines.

The WHO doesn't think cholera can be completely wiped out globally. This is because the bacteria can live in the environment without a human host. However, they believe it's possible to stop human-to-human transmission. Local elimination is possible, and Haiti is working to achieve this by 2022.

Cholera in society

Government and health

In many developing countries, cholera still spreads through contaminated water. Countries without good sanitation have more cases. Governments play a role in this. For example, the Zimbabwean cholera outbreak in 2008 was partly due to the government's actions. The Haitian government's inability to provide safe drinking water after the 2010 earthquake also led to more cholera cases.

If cholera starts to spread, a government's readiness is very important. Being able to stop the disease quickly can prevent many deaths and a big epidemic. Good disease tracking helps find outbreaks fast. This allows public health programs to find and control the cause, whether it's unsafe water or seafood.

The quality of a country's health care system also affects cholera control. If governments respond quickly and have vaccines ready, fewer people will die. But if vaccines are too expensive and governments don't provide them, poor people will suffer more.

Famous people with cholera

- Tchaikovsky, a famous composer, likely died from cholera in 1893.

- The 2010s Haiti cholera outbreak was the worst in recent history. It was traced to a United Nations base.

- Adam Mickiewicz, a Polish poet, is thought to have died of cholera in 1855.

- James K. Polk, the eleventh president of the United States, died of cholera in 1849.

- Nikola Tesla, a famous inventor, got cholera in 1873 when he was 17. He was very sick for nine months but fully recovered.

Examples from different countries

Zambia

Zambia has had many cholera outbreaks since 1977, mostly in its capital, Lusaka. In 2017, a cholera outbreak was declared after tests confirmed the bacteria. Cases quickly increased from hundreds to thousands.

The Zambian Ministry of Health worked with partners to fight the outbreak. They increased chlorine in the city's water, provided emergency water, and tested water quality. They also improved tracking, managed cases, trained health workers, and gave cholera vaccines.

India

The city of Kolkata, India, is sometimes called the "homeland of cholera." It has regular outbreaks, especially during rainy seasons. India has many people, unsafe drinking water, and poor sanitation. These conditions are perfect for Vibrio cholerae to survive and spread.

Democratic Republic of Congo

In Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo, cholera has had a lasting impact. Cholera pandemics in the 1800s and 1900s helped the science of epidemiology grow. More recently, it has pushed forward ideas in disease ecology and how cells work.

|

See also

In Spanish: Cólera para niños

In Spanish: Cólera para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |