Pedro II of Brazil facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pedro II |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

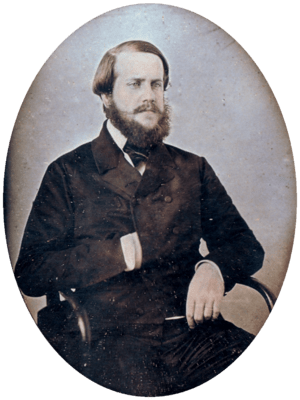

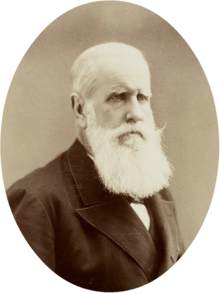

Dom Pedro II around age 61, c. 1887

|

|||||

| Emperor of Brazil | |||||

| Reign | 7 April 1831 – 15 November 1889 | ||||

| Coronation | 18 July 1841 Imperial Chapel |

||||

| Predecessor | Pedro I | ||||

| Successor | Monarchy abolished | ||||

| Regents | See list (1831–1840) | ||||

| Prime ministers | See list | ||||

| Head of the Imperial House of Brazil | |||||

| Tenure | 7 April 1831 – 5 December 1891 | ||||

| Predecessor | Pedro, Emperor of Brazil | ||||

| Successor | Isabel, Princess Imperial | ||||

| Born | 2 December 1825 Palace of São Cristóvão, Rio de Janeiro, Empire of Brazil |

||||

| Died | 5 December 1891 (aged 66) Paris, France |

||||

| Burial | 5 December 1939 Cathedral of São Pedro de Alcântara, Petrópolis, Brazil |

||||

| Spouse |

Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies

(m. 1843; died 1889) |

||||

| Issue detail |

|

||||

|

|||||

| House | Braganza | ||||

| Father | Pedro I of Brazil | ||||

| Mother | Maria Leopoldina of Austria | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Dom Pedro II (born December 2, 1825 – died December 5, 1891) was the second and last emperor of Brazil. He was often called the Magnanimous (Portuguese: O Magnânimo). He ruled for over 58 years. Pedro was born in Rio de Janeiro. He was the seventh child of Emperor Dom Pedro I of Brazil and Empress Dona Maria Leopoldina. This made him a member of the Brazilian branch of the House of Braganza.

When he was only five years old, his father suddenly gave up the throne and left for Europe in 1831. This made young Pedro the emperor. His childhood was often sad and lonely. He had to spend a lot of time studying to prepare for his future role as ruler. The political fights and secrets he saw during this time shaped him. He grew up to be a man who felt a strong duty to his country and people. Yet, he also started to dislike being emperor.

Pedro II took over an empire that was almost falling apart. But he helped Brazil become a strong country on the world stage. Brazil became known for its stable government, freedom of speech, and respect for people's rights. It also had a growing economy and a unique government style: a working parliamentary monarchy. Brazil won important wars, like the Platine War, the Uruguayan War, and the Paraguayan War. Pedro II also worked hard to end slavery, even though many powerful people were against it. He loved learning and supported science and culture. Famous people like Charles Darwin and Victor Hugo admired him.

Most Brazilians did not want to change their government. But Pedro II was overthrown in a sudden coup d'état. This was a takeover by a small group of military leaders who wanted a republic with a dictator. Pedro II was tired of being emperor and worried about the monarchy's future. He did not fight against being removed from power. He also did not support any attempts to bring the monarchy back. He spent his last two years living simply in Europe.

Pedro II's reign ended in an unusual way. He was very popular and respected when he was overthrown. Some of his achievements were lost as Brazil entered a long period of weak governments and economic problems. The people who exiled him later saw him as a good example for the new Brazilian Republic. Years after his death, his good name was restored. His remains were brought back to Brazil with celebrations across the country. Many historians see him as one of Brazil's greatest leaders.

Contents

Early Life of Emperor Pedro II

Birth and Childhood

Pedro was born on December 2, 1825, at 2:30 AM. His birthplace was the Palace of São Cristóvão in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He was named after Saint Peter of Alcantara. His full name was very long! Because his father was Emperor Dom Pedro I, Pedro was part of the Brazilian House of Braganza. From birth, he was called Dom, which means "Lord".

Pedro was the only son of Pedro I who lived past infancy. On August 6, 1826, he was officially named the heir to the Brazilian throne. He received the title of Prince Imperial. His mother, Empress Maria Leopoldina, died on December 11, 1826. Pedro was only one year old. A few years later, his father married Princess Amélie of Leuchtenberg. Pedro grew to love her like a mother.

On April 7, 1831, his father suddenly gave up the throne. Pedro I wanted to help his daughter Maria II get her Portuguese throne back. He also faced political problems in Brazil. Pedro I and Amélie left for Europe. They left five-year-old Prince Pedro behind, and he became Emperor Dom Pedro II.

Becoming Emperor at a Young Age

When Pedro I left, he chose three people to care for his son and daughters. The first was José Bonifácio de Andrada. He was a friend and important leader during Brazil's independence. He became Pedro's guardian. The second was Mariana de Verna. She had been Pedro's governess since he was born. As a child, Pedro called her "Dadama". He saw her as a second mother and kept using the nickname. The third person was Rafael, an Afro-Brazilian veteran of the Cisplatine War. Pedro I trusted him deeply and asked him to look after his son. Rafael did this for the rest of his life.

In December 1833, Bonifácio was replaced by another guardian. Pedro II spent most of his days studying. He only had two hours for fun. He was very smart and learned easily. But the long hours of study and preparing to be emperor were hard. He had few friends his age and little contact with his sisters. This, along with losing his parents, made Pedro II's childhood unhappy and lonely. He became a shy person who found comfort in books.

Since 1835, people had talked about letting the young Emperor rule before he turned 18. His becoming emperor had led to many problems. The regency that ruled for him faced constant fights between political groups. Rebellions broke out across the country. By 1840, politicians had lost faith in their ability to rule alone. They saw Pedro II as a leader who was needed for the country to survive. When asked if he wanted to take full power, Pedro II shyly agreed. The next day, July 23, 1840, the Brazilian Parliament officially declared 14-year-old Pedro II old enough to rule. He was later crowned on July 18, 1841.

Brazil's Stability and Growth

Establishing Imperial Authority

Ending the regency brought stability to the government. People across Brazil saw Pedro II as a true leader. His position put him above political arguments. However, he was still a shy and unsure young man. This was due to his difficult childhood. Behind the scenes, a group of palace staff and politicians, called the "Courtier Faction," gained influence over the young Emperor. Pedro II was sometimes used by these courtiers against their rivals.

The Brazilian government arranged for Pedro II to marry Princess Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies. They were married by a representative in Naples on May 30, 1843. When Pedro II saw her in person, he was disappointed. Teresa Cristina was short and a bit heavy. He did not hide his feelings. Some say he turned his back, others that he was so shocked he had to sit down. That evening, Pedro II cried and told Mariana de Verna, "They have tricked me, Dadama!" It took hours to convince him to go through with the marriage. The wedding ceremony happened the next day, September 4.

In late 1845 and early 1846, the Emperor traveled through Brazil's southern provinces. He visited São Paulo, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul. He was happy with the warm welcome he received. By then, Pedro II had grown up. He was a tall, handsome man with blue eyes and blond hair. His weaknesses faded, and his strong character showed. He became confident, fair, hardworking, polite, and patient. He kept his feelings under control. This period also saw the end of the Courtier Faction. Pedro II began to truly rule. He removed the courtiers from his inner circle without causing public trouble.

Ending the Slave Trade and Facing War

Pedro II faced three big challenges between 1848 and 1852. The first was stopping the illegal slave trade. This trade had been banned in 1826 by a treaty with the United Kingdom. But it continued. The British government passed the Aberdeen Act in 1845. This law allowed British warships to stop Brazilian ships and seize any involved in the slave trade. While Brazil dealt with this, the Praieira revolt started on November 6, 1848. This was a fight between local political groups in Pernambuco. It was stopped by March 1849.

On September 4, 1850, the Eusébio de Queirós Law was passed. This law gave the Brazilian government power to fight the illegal slave trade. With this new tool, Brazil worked to stop importing slaves. By 1852, this first problem was solved. Britain accepted that the trade had been stopped.

The third challenge was a conflict with the Argentine Confederation. This was about control over lands near the Río de la Plata and free travel on its waters. Since the 1830s, Argentina's leader, Juan Manuel de Rosas, had supported rebellions in Uruguay and Brazil. In 1850, Brazil finally dealt with Rosas. Brazil, Uruguay, and unhappy Argentines formed an alliance. This led to the Platine War and Rosas's overthrow in February 1852. Pedro II's calm leadership and determination were very important.

Brazil's success in these challenges made the country much more stable and respected. Brazil became a strong power in South America. Other countries in Europe saw Brazil as a modern nation with freedom of the press and civil rights. Its parliamentary monarchy was very different from the dictatorships and instability common in other South American nations.

Growth and Progress

Pedro II and Politics

In the early 1850s, Brazil was stable and its economy was doing well. With Honório Hermeto Carneiro Leão as prime minister, the Emperor started his own big plans. These included "conciliation" (bringing political groups together) and "material developments" (improving the country). Pedro II's reforms aimed to reduce political fighting and boost the economy and infrastructure. Brazil was connected by railroads, telegraph lines, and steamships.

People at home and abroad believed these achievements were possible because Brazil was a monarchy and because of Pedro II's character. Pedro II was not just a symbol like a British monarch. He also wasn't an absolute ruler like a Russian czar. He worked with elected politicians, business leaders, and the public. Pedro II's active role in politics was key to the government. He used his influence to guide the country. His guidance was essential, but he never ruled alone. He had to seem fair to all political parties. He also had to work with what the public wanted.

The Emperor's political successes came from his calm and cooperative way of dealing with problems and politicians. He was very tolerant. He rarely got upset by criticism or even mistakes. He didn't have the power to force his ideas without support. His teamwork approach helped the nation move forward and made the political system work well. He respected the power of the legislature, even when they disagreed with him. Most politicians valued his role. Many had lived through the time when there was no emperor. That period had been full of fights between political groups. They believed Pedro II was "necessary for Brazil's peace and wealth."

Imperial Family Life

Pedro II's marriage to Teresa Cristina started poorly. But with time, patience, and the birth of their first child, Afonso, their relationship got better. Later, Teresa Cristina had more children: Isabel (1846), Leopoldina (1847), and Pedro Afonso (1848). Both boys died very young. This deeply saddened the Emperor and changed his view of Brazil's future. Even though he loved his daughters, he didn't think Princess Isabel, his heir, could succeed as empress. He felt the ruler needed to be male for the monarchy to last. He increasingly believed the imperial system depended only on him. Isabel and her sister received a great education. However, they were not prepared to govern the nation. Pedro II kept Isabel from government work and decisions.

Pedro II worked very hard. His daily routine was tough. He usually woke up at 7:00 AM and didn't sleep before 2:00 AM. His whole day was spent on state matters. His little free time was used for reading and studying. The Emperor wore a simple black suit for his daily routine. For special events, he wore court clothes. He only wore his full royal outfit, with crown, cape, and scepter, twice a year. This was for the opening and closing of the Parliament. Pedro II expected politicians and officials to meet the same high standards he set for himself. He chose civil servants based on their honesty and skill. He lived simply, once saying: "Useless spending is like stealing from the Nation." After 1852, royal balls and gatherings stopped. He also refused to ask for more money for his personal expenses.

Supporting Arts and Sciences

In 1862, the Emperor wrote in his private journal: "I was born to dedicate myself to culture and sciences." He always wanted to learn. Books were a refuge from his duties. Pedro II was interested in many subjects. These included anthropology, history, geography, geology, medicine, law, religious studies, philosophy, painting, sculpture, theater, music, chemistry, physics, astronomy, poetry, and technology. By the end of his rule, his palace had three libraries with over 60,000 books. He loved linguistics and learned many languages. He could speak and write Portuguese, Latin, French, German, English, Italian, Spanish, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, Sanskrit, Chinese, Occitan, and Tupi.

He became the first Brazilian photographer in March 1840. He had a special room for photography and another for chemistry and physics. He also built an astronomical observatory. The Emperor believed education was vital for the country. He was a great example of the value of learning. He once said: "If I were not an Emperor, I would like to be a teacher. I don't know of a nobler task than guiding young minds."

During his reign, the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute was created. This helped research and protect history, geography, culture, and social sciences. The Imperial Academy of Music and National Opera and the Pedro II School were also founded. The Pedro II School became a model for others in Brazil. He used his own money to give scholarships to Brazilian students. They could study at universities and art schools in Europe. He also helped fund the Institute Pasteur and Wagner's Bayreuth Festspielhaus. Charles Darwin said of him: "The Emperor does so much for science, that every scientific man is bound to show him the utmost respect."

Pedro II became a member of important groups like the Royal Society and the French Academy of Sciences. He wrote letters to many scientists, philosophers, and artists. Many became his friends, including Richard Wagner, Louis Pasteur, and Alexander Graham Bell. Victor Hugo told the Emperor: "Sire, you are a great citizen, you are the grandson of Marcus Aurelius."

Conflict with the British Empire

At the end of 1859, Pedro II traveled to provinces north of the capital. He visited Espírito Santo, Bahia, Sergipe, Alagoas, Pernambuco, and Paraíba. He returned in February 1860 after four months. The trip was a great success. People welcomed the Emperor warmly everywhere. The first half of the 1860s was a time of peace and wealth in Brazil. Civil liberties were protected. Freedom of speech had existed since Brazil's independence. Pedro II strongly defended it. He read newspapers from the capital and provinces to understand public opinion.

He also learned about the country by meeting people directly. He held public audiences every Tuesday and Saturday. Anyone, from any social class, including slaves, could meet him. They could present their requests and stories. Visits to schools, prisons, factories, and other public places also helped him gather information.

This peace was broken when the British consul in Rio de Janeiro, William Dougal Christie, almost started a war. Christie sent an ultimatum with harsh demands. These came from two small incidents in late 1861 and early 1862. First, a merchant ship sank off the coast of Rio Grande do Sul. Its goods were stolen by locals. Second, drunken British officers caused trouble in Rio and were arrested.

The Brazilian government refused to give in. Christie then ordered British warships to capture Brazilian merchant ships for payment. Brazil prepared for what seemed like an upcoming war. Pedro II was the main reason Brazil resisted. He refused to give in. This surprised Christie, who then suggested a peaceful solution through international talks. Brazil presented its demands. When the British government's position weakened, Brazil cut off diplomatic ties with Britain in June 1863.

The Paraguayan War

Joining the War Effort

As war with the British Empire seemed possible, Brazil had to focus on its southern borders. Another civil war had begun in Uruguay. This conflict led to Brazilians being killed and their property stolen in Uruguay. Brazil's government decided to step in. They feared looking weak if they didn't act. A Brazilian army invaded Uruguay in December 1864. This started the short Uruguayan War, which ended in February 1865.

Meanwhile, the leader of Paraguay, Francisco Solano López, used the situation to make his country stronger. The Paraguayan Army invaded the Brazilian province of Mato Grosso. This started the Paraguayan War. Four months later, Paraguayan troops invaded Argentine land. This was a step toward attacking Rio Grande do Sul.

Pedro II knew about the chaos in Rio Grande do Sul. He also knew its military leaders were not able to stop the Paraguayan army. So, he decided to go to the front lines himself. His cabinet, Parliament, and Council of State objected. But Pedro II declared: "If they can stop me from going as an Emperor, they cannot stop me from giving up my throne and going as a Fatherland Volunteer." This referred to Brazilians who volunteered for the war. The Emperor himself was called the "number-one volunteer."

Given permission to leave, Pedro II arrived in Rio Grande do Sul in July. He traveled by horse and wagon, sleeping in a tent. In September, he reached Uruguaiana, a Brazilian town surrounded by the Paraguayan army. The Emperor rode close to Uruguaiana, but the Paraguayans did not attack him. To avoid more bloodshed, he offered surrender terms to the Paraguayan commander, who accepted. Pedro II's leadership and personal example helped push back the Paraguayan invasion of Brazil. Before returning to Rio de Janeiro, he met the British diplomat Edward Thornton. Thornton apologized on behalf of Queen Victoria and the British Government for the earlier crisis. The Emperor saw this diplomatic win as enough and renewed friendly relations.

Victory and Its High Costs

Against all expectations, the war lasted five years. During this time, Pedro II focused all his energy on the war. He worked tirelessly to gather and equip troops for the front lines. He also pushed for new warships for the navy. In November 1866, he told the Countess of Barral that "the war should be finished as honor demands, no matter the cost." Despite difficulties and tiredness from the war, he remained determined. Rising casualties did not stop him from pursuing what he saw as Brazil's just cause. He was even ready to give up his own throne for an honorable outcome. A few years earlier, Pedro II wrote in his journal: "What fear could I have? That they take the government from me? Many better kings than I have lost it, and to me it is no more than the weight of a cross which it is my duty to carry."

At the same time, Pedro II worked to stop fights between political parties from hurting the war effort. The Emperor overcame a serious political crisis in July 1868. This was caused by a disagreement between the cabinet and Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, the Brazilian commander-in-chief in Paraguay. Caxias was also a politician from the opposing party. The Emperor sided with him, leading to the cabinet's resignation. As Pedro II worked for victory, he supported the political groups that seemed most helpful. This harmed the monarchy's reputation. Its trusted role as a fair mediator was damaged in the long run. He did not care about his own position. He put the country's interest before any harm to the imperial system.

His refusal to accept anything less than total victory was key to the outcome. His persistence paid off when López died in battle on March 1, 1870. This ended the war. Pedro II turned down the Parliament's idea to build a statue of him to celebrate the victory. Instead, he chose to use the money to build elementary schools.

The Golden Age of Brazil

Ending Slavery in Brazil

In the 1870s, Brazil made great progress. Society benefited from reforms and growing wealth. Brazil's reputation for political stability and investment improved greatly. The Empire was seen as a modern and advanced nation, second only to the United States in the Americas. The economy grew fast, and many immigrants arrived. Railroads, shipping, and other modern projects were started. With "slavery set to end and other reforms planned, the chances for 'moral and material advances' seemed huge."

In 1870, few Brazilians were against slavery. Even fewer openly spoke against it. Pedro II, who did not own slaves, was one of the few who opposed it. Ending slavery was a sensitive topic. Slaves were used by everyone, from the richest to the poorest. Pedro II wanted to end the practice slowly to lessen the impact on the economy. He had no power to directly abolish slavery. So, he had to use all his skills to convince and gain support from politicians. His first public move was in 1850. He threatened to give up his throne unless Parliament made the Atlantic slave trade illegal.

After stopping the overseas slave trade, Pedro II focused on ending the enslavement of children born to slaves. He started drafting laws for this in the early 1860s. But the war with Paraguay delayed the discussion in Parliament. Pedro II openly asked for slavery to be gradually ended in his speech from the throne in 1867. He was heavily criticized. Critics said that ending slavery was his personal wish, not the nation's. He ignored the growing political damage to his image and the monarchy because of his support for abolition. Finally, a bill pushed by Prime Minister José Paranhos became law. This was the Law of Free Birth on September 28, 1871. It said that all children born to slave women after that date were free.

Travels to Europe and North Africa

On May 25, 1871, Pedro II and his wife traveled to Europe. He had wanted to go abroad for a long time. News arrived that his younger daughter, Leopoldina, had died in Vienna on February 7. This gave him a strong reason to leave Brazil. When he arrived in Lisbon, Portugal, he immediately went to the Janelas Verdes palace. There, he met his stepmother, Amélie of Leuchtenberg. They had not seen each other in forty years, and the meeting was very emotional. Pedro II wrote in his journal: "I cried from happiness and also from sorrow seeing my Mother so affectionate toward me but so aged and so sick."

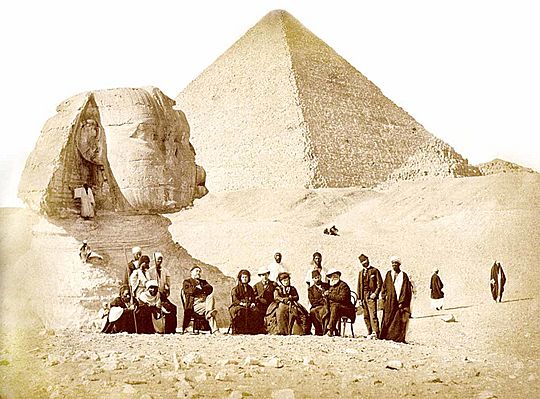

The Emperor then visited Spain, Great Britain, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Italy, Egypt, Greece, Switzerland, and France. In Coburg, he visited his daughter's tomb. He found this trip to be "a time of release and freedom." He traveled using the name "Dom Pedro de Alcântara." He wanted to be treated informally and stayed only in hotels. He spent his days seeing sights and talking with scientists and thinkers. The trip to Europe was a success. His behavior and curiosity earned him respect in the countries he visited. Brazil's and Pedro II's prestige grew even more during the tour. News arrived from Brazil that the Law of Free Birth had been approved. The imperial group returned to Brazil in triumph on March 31, 1872.

The Religious Issue

Soon after returning to Brazil, Pedro II faced an unexpected problem. The Brazilian clergy (Church leaders) had long been too few, undisciplined, and poorly educated. This led to a loss of respect for the Catholic Church. The government had started a plan to fix these problems. Since Catholicism was the state religion, the government had much control over Church matters. It paid clergy salaries, appointed priests, nominated bishops, and oversaw seminaries. To reform the Church, the government chose bishops who were educated and supported reform. However, as more capable men joined the clergy, they grew to dislike government control.

The bishops of Olinda and Belém were two of these new, educated, and eager Brazilian clerics. They were influenced by a movement called ultramontanism. In 1872, they ordered Freemasons to be removed from Catholic brotherhoods. In Europe, Freemasonry often meant being against religion. But in Brazil, many people, including politicians, were Freemasons. Pedro II himself was not a Freemason. The government, led by the Viscount of Rio Branco, tried twice to convince the bishops to change their order. But they refused. This led to their trial and conviction by the Superior Court of Justice. In 1874, they were sentenced to four years of hard labor. However, the Emperor changed this to just imprisonment.

Pedro II strongly supported the government's actions. He was a devoted Catholic. He believed Catholicism promoted important civil values. While he avoided anything unusual, he felt free to think for himself. The Emperor accepted new ideas, like Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. He said Darwin's laws "glorify the Creator." He was moderate in his religious beliefs. But he could not accept disrespect for civil law and government authority. He told his son-in-law: "[The government] has to make sure the constitution is obeyed. In these actions, there is no desire to protect masonry; but rather the goal of upholding the rights of the civilian power." The problem was solved in September 1875. The Emperor reluctantly agreed to pardon the bishops. The Holy See (the Pope's authority) then canceled the Church's orders.

Journeys to the United States, Europe, and Middle East

Once again, the Emperor traveled abroad. This time he went to the United States. His loyal servant Rafael, who had raised him, went with him. Pedro II arrived in New York City on April 15, 1876. From there, he traveled across the country. He went as far as San Francisco in the west, New Orleans in the south, Washington, D.C., and north to Toronto, Canada. The trip was a great success. Pedro II impressed Americans with his simple and kind manner.

He then crossed the Atlantic Ocean. He visited Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Greece, the Holy Land, Egypt, Italy, Austria, Germany, France, Britain, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Portugal. He returned to Brazil on September 22, 1877.

Pedro II's trips abroad had a deep effect on him. When traveling, he was mostly free from the rules of his job. Using the name "Pedro de Alcântara," he enjoyed moving around like an ordinary person. He even took a train trip alone with his wife. Only when traveling could the Emperor escape the formal life he knew in Brazil. It became harder to get back to his routine as head of state when he returned. After his sons died young, the Emperor's belief in the monarchy's future disappeared. His trips abroad now made him resentful of being emperor, a role he was given at age five. If he had no interest in securing the throne for the next generation before, he now had no desire to keep it going during his own lifetime.

Decline and Fall of the Empire

The Emperor's Decline

During the 1880s, Brazil continued to do well. Society became more diverse, and there was even a push for women's rights. However, letters written by Pedro II show a man who was tired of the world. He became more distant and pessimistic as he aged. He still respected his duty and carefully did what his job required, but often without excitement. Because he became "indifferent towards the fate of the regime" and did not act to support the imperial system when it was challenged, historians say the Emperor himself was mainly responsible for the monarchy's end.

Older politicians who had seen the dangers of government in the 1830s believed the Emperor was a vital source of authority. They thought he was essential for ruling and for the nation's survival. These older leaders began to die or retire. By the 1880s, they were mostly replaced by a new generation of politicians. These new leaders had not experienced the early years of Pedro II's rule. They had only known stable government and wealth. So, they saw no reason to support the imperial office as a unifying force. To them, Pedro II was just an old, sick man who had weakened his position by being too active in politics for decades. Before, he was above criticism. But now, every action and inaction was closely watched and openly criticized. Many young politicians did not care about the monarchy. When the time came, they did nothing to defend it. Pedro II's achievements were forgotten by the ruling class. By being so successful, the Emperor had made his own position seem unnecessary.

The lack of a male heir who could lead the nation also hurt the monarchy's long-term future. The Emperor loved his daughter Isabel. But he thought a female ruler was not right for Brazil's leader. He saw the death of his two sons as a sign that the Empire was meant to end. The political leaders also did not want a female ruler. Even though the Constitution allowed a woman to inherit the throne, Brazil was still very traditional. Only a male successor was thought capable of being head of state.

End of Slavery and the Coup

By June 1887, the Emperor's health was much worse. His doctors suggested he go to Europe for medical treatment. In Milan, he was very ill for two weeks, almost dying. While recovering in bed, on May 22, 1888, he received news that slavery had been abolished in Brazil. With a weak voice and tears in his eyes, he said, "Great people! Great people!" Pedro II returned to Brazil and arrived in Rio de Janeiro in August 1888. The "whole country welcomed him with an enthusiasm never seen before." People from everywhere showed their love and respect. With this devotion, the monarchy seemed very popular and strong.

Brazil had great international respect in the last years of the Empire. It had become a rising power in the world. Predictions that ending slavery would cause economic problems did not come true. The 1888 coffee harvest was successful. However, ending slavery caused rich and powerful coffee farmers to support republicanism. These farmers had great political and economic power. Republicanism was an idea for the elite and did not have much support in the provinces. The mix of republican ideas and positivism among lower and middle army officers led to a lack of discipline in the army. This became a serious threat to the monarchy. These officers dreamed of a strong republic, which they believed would be better than the monarchy.

Most Brazilians did not want to change the form of government. But civilian republicans began pressuring army officers to overthrow the monarchy. They launched a coup d'état. They arrested Prime Minister Afonso Celso, Viscount of Ouro Preto and started the republic on November 15, 1889. The few people who saw what happened did not realize it was a rebellion. Historian Lídia Besouchet noted that "rarely has a revolution been so minor." During the event, Pedro II showed no emotion, as if he didn't care about the outcome. He rejected all suggestions from politicians and military leaders to stop the rebellion. When he heard about his removal, he simply said: "If it is so, it will be my retirement. I have worked too hard and I am tired. I will go rest then." He and his family were sent to live in Europe on November 17.

Exile and Lasting Impact

Final Years in Europe

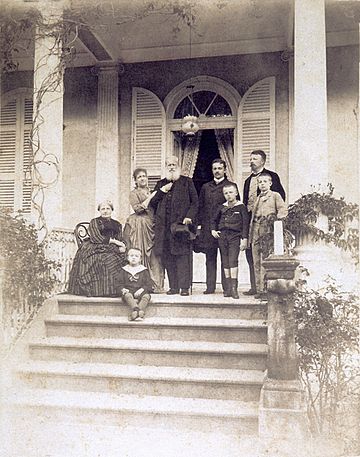

Teresa Cristina died three weeks after they arrived in Europe. Isabel and her family moved to another place. Pedro settled first in Cannes and later in Paris. Pedro's last few years were lonely and sad. He lived in simple hotels with little money. He wrote in his journal about dreams of returning to Brazil. He never supported bringing the monarchy back. He once said he did not want "to return to the position which I occupied, especially not by means of conspiracy of any sort." One day, he caught an infection that quickly turned into pneumonia. Pedro quickly got worse and died at 12:35 AM on December 5, 1891. His family was around him. His last words were "May God grant me these last wishes—peace and prosperity for Brazil." While his body was being prepared, a sealed package was found in the room. Next to it was a message from the Emperor: "It is soil from my country, I wish it to be placed in my coffin in case I die away from my fatherland."

Isabel wanted a quiet, private burial. But she agreed to the French government's request for a state funeral. On December 9, thousands of mourners attended the ceremony at La Madeleine. Besides Pedro's family, many European royals were there. Also present were General Joseph Brugère, representing President Sadi Carnot, and other French government officials. Nearly all members of the Institut de France attended. Other governments from the Americas, Europe, and even the Ottoman Empire, Persia, China, and Japan sent representatives. After the service, the coffin was taken in a procession to the railway station. It began its trip to Portugal. About 300,000 people lined the route in the rain and cold. The journey continued to the Church of São Vicente de Fora near Lisbon. Pedro's body was buried there on December 12.

The Brazilian republican government, "fearful of a backlash resulting from the death of the Emperor," banned any official reaction. Still, Brazilians were not uncaring about Pedro's death. There were "huge reactions in Brazil, despite the government's effort to suppress. There were signs of sadness throughout the country: businesses closed, flags at half-mast, black armbands, church bells ringing, religious ceremonies." Masses were held for Pedro across Brazil. He and the monarchy were praised in the speeches that followed.

Pedro II's Legacy

After he was overthrown, Brazilians still felt connected to the former Emperor. He remained a popular and highly praised figure. This was especially true among people of African descent. They linked the monarchy with freedom because of his and his daughter Isabel's role in ending slavery. The continued support for the deposed monarch is largely due to a common belief that he was a truly "wise, kind, strict, and honest ruler," said historian Ricardo Salles. The positive view of Pedro II, and a longing for his rule, only grew. This happened as Brazil quickly fell into economic and political problems. Brazilians blamed these problems on the Emperor's overthrow.

Republicans felt strong guilt. This became more clear after the Emperor's death in exile. They praised Pedro II, seeing him as a model of republican ideals. They also saw the imperial era as an example for the young republic to follow. In Brazil, the news of the Emperor's death "caused a real sense of regret." This was true even among those who did not want the monarchy back. They still recognized the good qualities and achievements of their former ruler. His remains, and those of his wife, were brought back to Brazil in 1921. This was in time for the 100th anniversary of Brazilian independence. The government gave Pedro II honors fit for a head of state. A national holiday was declared. The return of the Emperor as a national hero was celebrated across the country. Thousands attended the main ceremony in Rio de Janeiro. According to historian Pedro Calmon, "elderly people cried. Many knelt down. All clapped hands. There was no difference between republicans and monarchists. They were all Brazilians." This tribute marked the reconciliation of Republican Brazil with its monarchical past.

Historians have a high opinion of Pedro II and his reign. There is a lot of scholarly writing about him. Except for the time right after he was overthrown, most of it is very positive and even praising. Several historians in Brazil have called him the greatest Brazilian. Like the republicans, historians point to the Emperor's good qualities as an example to follow. However, none go so far as to suggest bringing back the monarchy. Historian Richard Graham noted that "most twentieth-century historians... have looked back on the period [of Pedro II's reign] fondly. They use their descriptions of the Empire to criticize—sometimes subtly, sometimes not—Brazil's later republican or dictatorial governments."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pedro II de Brasil para niños

In Spanish: Pedro II de Brasil para niños

- Dom Pedro aquamarine, a large aquamarine gem named after Pedro II and his father.